PLAN 502: Week 7

advertisement

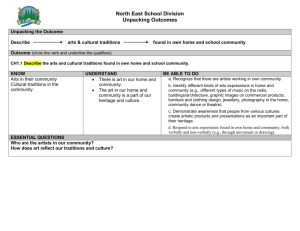

PLAN 502: Week 7 Chapters on public-private partnerships, and the role of power in planning Agenda for Today Next Wednesday, from noon to 1:30, there will be an international luncheon in Building 355, Room 211. International students will be the guests of honour. Policy papers are due today. To follow up on our discussion of Forester and Healey last week, I will show a short clip of a film about the Cowichan watershed called “Resilience,” and I originally hoped to have a guest speaker, Christine Brophy, who is part of the process of seeking to heal the river and the overall watershed. She is knowledgeable about multi-stakeholder processes in the context of a specific place and of restoration work. But she will come next week. Introduction to Part IV: Planning in Action The editors note that a “common theme [in the articles in this section] is the frequent deviation from the logic of prevailing models, such as the ‘rational planning model’ or the ‘public-private partnership’. These cases remind us that planning dynamics are embedded in local contexts, that institutional arrangements are complex and fluid…” They note that, in the case of public-private partnerships, there is the conundrum: “how to retain public accountability and citizen deliberation in situations where confidentiality is mandated by private sector involvement in a competitive market process”. Introduction to Part IV: Planning in Action Other articles deal with the real role of power in planning decisions and, by contrast, the attempt to create alternative structures for community control throughout American history (one can find similar examples in Canadian history). Matti Siemiatycki: Public-Private Partnerships Public-private partnerships (PPPs) have become very popular in recent decades. The most popular version is the design-buildfinance-operate (DBFO) model. As Matti Siemiatycki notes, “In theory, the DBFO model of public-private ownership seeks to balance the advantage of government control of the strategic allocation of scarce resources in the protection of the broad public interest, with the benefit of infusing competitive forces into the delivery of public services to increase efficiency.” (p. 241) Matti Siemiatycki: PPPs Hypothetically, “such an approach can be seen as an attempt by cash-strapped governments to take advantage of private-sector access to capital to finance projects, deliver innovation, and managing risk without the public sector relinquishing control of strategic objectives as occurred under outright privatization and deregulation.” (p. 241). The author wants to know if this new model overcomes the deficiencies of past processes where there was undue “political influence, interest-group lobbying, [and] poor transparency…” (p. 242) Matti Siemiatycki: PPPs He uses the Richmond-Airport-Vancouver (RAV) urban rail project – now known as the Canada Line – as his test case. The Canada Line is the largest urban PPP in urban transit ever undertaken in Canada. He claims that “the planning of the RAV line… has largely failed to achieve the desired benefits of eliminating cost escalations during the planning process, delivering greater technological innovation, or improving procedural accountability.” (p. 243) The Canada Line • According to Siemiatycki, RAV was chosen despite the fact that improving bus infrastructure had been previously seen as the top transit priority. RAV had the virtue of “being most conducive to meeting the needs of local and senior governments… [and] it had added appeal for special grants for the [2010] Olympic Games…” (p. 248). The ability to attract private investors was also a key factor in its choice. See table 13.2 on pp. 250-251. Matti Siemiatycki: PPPs As Flyvjerg, at al. (2003) note, in theory, PPPs 1)increase the rationality of project development, as different private firms compete to find the best technical solution to the government’s performance specifications; 2) they boost accountability because private firms’ money is also on the line and so they have a vested interest in ensuring that the technology is good and the efficiency of the process is high, and 3) they divide the risk between the public and private sectors. Despite this narrative, many studies have shown that PPPs are not all they are cracked up to be (see summary table on p. 245). Matti Siemiatycki: PPPs Beginning in 2000, Translink (the greater Vancouver regional transit authority), the provincial government, the federal government, and the airport authority formed RAVCO – a subsidiary of Translink – to “coordinate the procurement, design, financing, and implementation of the RAV project.” (p. 249). The City of Vancouver, the City of Richmond, the Greater Vancouver Regional District, and the port authority were given special stakeholder status within RAVCO. RAVCO hired a consulting firm to investigate the feasibility of developing the line as a PPP. Matti Siemiatycki: PPPs In the first phase, RAVCO sought to create performance specifications based on the policy directions and interests of the various parties. This was to set a standard for private-sector actors to innovate to create the best system at the lowest cost. There was then a protracted procurement process to determine the preferred company. As Siemiatycki notes on p. 253, an insider even admitted that the RAV was foreordained, that other alternatives were discounted – both in terms of location and technology. The desire for an Olympics legacy was a huge motivation. Matti Siemiatycki: PPPs RAVCO has good intentions. As Siemiatycki notes, “RAVCO intended to overcome the need for secrecy… by using international best practices of public disclosure, accountability, and govern-ance, such as enhancing online posting of technical and meeting minutes, ongoing citizen engagement, and public access to internal documents…. Nevertheless… the need for secrecy and the prevalence of commercially confidential information associated with the competitive tendering process appears to be incongruent with the need for openness and transparency associated with an accountable planning process.”(p. 255) Matti Siemiatycki: PPPs Page 257 (Table 13.3) contains an interesting table on the donations to political parties by the various companies competing for the contract or pieces of it. “Despite the potential for there to be the appearance of corporate conflicts of interest, requests to have the entire process reviewed during the planning stages by the auditor general of British Columbia – the agency charged with protecting the public interest with the public interest – were denied repeatedly.” Also, by this point, a Richmond city councillor had begun to express doubts about the integrity of the consultation process. Matti Siemiatycki: PPPs On the financial front, at one point when it seemed decision-makers would reject the project, it came to be realized that the budget of $1.559 billion was going to be shouldered primarily by the public sector ($1.35 billion). The estimate for the whole project later went up to $1.9 billion, or significantly above what had been projected. So, at the end of day, despite the decision-makers’ best intentions, the project didn’t a) achieve cost efficiencies; b) did not enable technological innovation (the route and the technology had basically been already decided); c) was not particularly consultative, and d) did not end corporate influence and political interference. James deFilippis: Utopianism and Communal Traditions in the U.S. His frontispiece quote suggests that the left in the U.S. suffers from amnesia. It doesn’t know its own history. His article has three parts: the 19th century experiments with collectivism and community control, the 1960s when the community development emerged, and more recent times where that movement has become institutionalized and professionalized. He starts by talking about the history of black “organized communities” (mostly before the end of the Civil War) where blacks in the northern U.S. and southern Ontario sought to segregate themselves to build up the necessary resources to make it on their own. James deFilippis: Utopianism and Communal Traditions in the U.S. In other words, it wasn’t genuine cooperativism or collectivism, but a waystation to individual success. The overall impact of these communities was apparently relatively slight. He notes that the vision behind these communities was not dissimilar to that of Booker T. Washington, who wanted blacks to segregate themselves and build up their capacity as tradespeople or small-scale capitalists so they could eventually be accepted on an equal footing. James deFilippis: Utopianism and Communal Traditions in the U.S. In addition to the more individualist and capitalistic traditions just mentioned, there were also utopian, communistic experiments founded on a blending of “Jeffersonian agrarian democracy… and British socialism” (p. 270. Robert Owen, for instance, founded his New Harmony in Indiana, which failed after two years and ate up most of his fortune; it was one of a number of attempts to build a cooperative society, whether secular or under the flag of religion. James deFilippis: Utopianism and Communal Traditions in the U.S. Owen was a real pioneer. He took over a textile factory and associated village (New Lanark) in Scotland populated by 1500 adults and 500 children (from poor houses and orphanages). Before the takeover, people were relatively well-treated but social dysfunction was rife. He ended the token system where workers were paid in tokens that could only be redeemed at the company store for shoddy goods. He started selling quality goods at just over the wholesale price, and put tight controls on the distribution of alcohol. He also insisted that children should go to school up to a certain age. Social dysfunction declined drastically. In 1810, he advocated for a 10-hour day and implemented it. Shortly thereafter, he advocated for an 8-hour day. James deFilippis: Utopianism and Communal Traditions in the U.S. He also founded the first consumer co-ops, whose (Rochdale) principles still animate all co-ops today. He also proposed co-operative communities where people would have private apartments, but otherwise would live and work in common. None of these were successfully established. He was criticized by Marx as being a “utopian socialist.” In the ‘60s, three new overlapping movements emerged in the U.S.: the Black Power movement, the direct democracy movement, and the cooperative living movement. One long-lasting institution to emerge from this time was the community development corporation (CDC). James deFilippis: Utopianism and Communal Traditions in the U.S. According to Wikipedia, a “community development corporation (CDC) is a not-for-profit organization incorporated to provide programs, offer services and engage in other activities that promote and support community development. CDCs usually serve a geographic location such as a neighbourhood or a town. They often focus on serving lower-income residents or struggling neighborhoods. They can be involved in a variety of activities including economic development, education, community organizing and realestate development. These organizations are often associated with the development of affordable housing.” James deFilippis: Utopianism and Communal Traditions in the U.S. A couple of examples in Canada are the 1000 Islands Community Development Corporation in Eastern Ontario (www.tcdc.ca/) and the Chukuni CDC near the Ontario/ Manitoba border (http://www.chukuni.com/). The origin in the U.S. was the “War on Poverty,” with its Office of Economic Opportunity and “community action agencies.” The Community Action Program oversaw the CAAs and operated on the principle of “maximum feasible participation.” Some CAAs became watchdogs for service delivery programs; others were more confrontational. This eventually led to a re-orientation of urban policy towards economic development. James deFilippis: Utopianism and Communal Traditions in the U.S. In 1969, the Federal Community Self-Determination Act was passed leading to the creation of first CDCs. Another shift in urban policy was the Model Cities program, which put “control over anti-poverty/ neighbourhood development policies back into the hands of city governments.” (p. 272). At the same time, the Black Power movement came on the scene as a more militant offshoot of the civil rights movement seeking community control of economic resources. In the end, it was dismissively characterized as a ‘60s version of Booker T. Washington with a veneer of radicalism. James deFilippis: Utopianism and Communal Traditions in the U.S. There was also a direct democracy movement that rejected both the class politics of the left and the centralized social welfare policies of the New Deal/ Great Society. Milton Kotler, together with Jane Jacobs (who, by this point, had moved to Toronto), argued for the decentralization of political and economic control to neighbourhoods. While some reforms were achieved, in general the business as usual of municipal politics prevailed. In Canada, however, quite significant municipal reform movements occurred in Vancouver, Toronto, Montreal, and Winnipeg that resulted in much more politically sensitive mayors, councils, and planning directors who encouraged real consultation. James deFilippis: Utopianism and Communal Traditions in the U.S. The movement of communes and co-ops (less so the latter) was relatively short-lived and on a quite small scale and did little to shift the mainstream of society. Instead of “small is beautiful,” it was often “small is irrelevant.” The author claims a mistake was made in separating class at work from community at home and neighbourhood. He discusses the Industrial Areas Foundation of Saul Alinsky, and the various organizations it spawned, and describes them indirectly as a kind of advocacy planning movement without an adequate theory or ideology. While nonideological, they did not shirk confrontation. James deFilippis: Utopianism and Communal Traditions in the U.S. In the late ‘70s and ‘80s, CDCs – borne in the ‘60s – became more profit-oriented and professionalized, in part because of the need to compete in the capitalist marketplace. Instead of being vehicles of community control, they became more vehicles of economic development. As of 2002, there were 3600 CDCs in the U.S. While achieving much in the realms of affordable housing and social service provision, etc., they also lost what federal funding they had enjoyed. They had to become more entrepreneurial to stay afloat. A rather blunt assessment from the Ford Foundation stated that “with rare exceptions, the 1960s are now as much history for them (CDCs) James deFilippis: Utopianism and Communal Traditions in the U.S. as for the rest of American society. One can’t very hurl his body into the path of an oncoming bulldozer when he (or she) is the developer.” One exception to the decline in CDC ideals is ShoreBank, founded in 1973 to provide financial services to African-American communities in Chicago that were being neglected by traditional financial institutions. “It was the nation's first community development bank. During its 37 years of operation, ShoreBank played a critical role in stabilizing and rebuilding many of Chicago's lowincome neighborhoods and eventually expanded globally, setting the standard for the development of a socially just finance industry.” James deFilippis: Utopianism and Communal Traditions in the U.S. “As its range of financial products grew, so did its geographic reach and influence in the banking industry. ShoreBank expanded into low-income communities in Detroit, Cleveland, Michigan's Upper Peninsula, Arkansas, and the Pacific Northwest. Its influence in Arkansas influenced Bill Clinton, then governor to propose the Community Development Financial Institutions Act, which he signed in 1994. In addition, ShoreBank executives assisted in the development of the international microfinance industry.” James deFilippis: Utopianism and Communal Traditions in the U.S. After the collapse of the Berlin Wall, the corporation's international affiliate, ShoreBank Advisory Services, assisted banks in Central Europe with small business lending. It also assisted Mohammed Yunis in incorporating the micro-lending Grameen Bank in Bangladesh. In 1997, it collaborated with EcoTrust to create ShoreBank Pacific, the nation’s first environmental bank. While ShoreBank never received any federal assistance and eventually became involvent (2010), a number of its independent branches – in Detroit, Chicago, and Northwest, have remained functioning. Champlain Housing Trust (http://www.getahome.org/) is another praiseworthy CDC-like model. Bent Flyvbjerg: Bringing Power to Planning Research He cites Friedmann on the need to bring power as an explicit dimension into the conceptual framework of planning theory. Flyvbjerg cities his own experience as a young Danish intern studying the arguments for and against urban decentralization as they related to social, educational, and health services. He report was sent out to heads of those service departments, and it was clear from their comments that they had no tolerance for the idea of decentralization; it just wasn’t in the cards. He then talks about his experience as a young academic in researching the fate of the “Aalborg Project” in Denmark. Aalborg, main centre for northern Jutland in Denmark Bent Flyvbjerg: Bringing Power to Planning Research The upshot of this part is that the city government initially had an enlightened vision of “preserving the historical character of the downtown area; radically improving public transit; enhancing environmental protection; developing an integrated network of bike paths, pedestrian malls, and green spaces; and developing housing stock.” (p. 295) The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) touted it as a model for international adoption. However, a decade and a half later its promise had largely failed to be realized. Why? One reason he feels is the undue influence of the Chamber of Commerce, which received special treatment not accorded to any other body. Bent Flyvbjerg: Bringing Power to Planning Research “…the rationality of the chamber could be summarized in the following three propositions: 1)What is good for business is good for Aalborg; 2) people driving automobiles are good for business, whereas, conversely, what is bad for drivers is bad for Aalborg. In short ‘the car is king’ was the rationality of the chamber” (pp. 298-299). As it turned out, the chamber secretly negotiated changes to the planners’ proposals before they were submitted to the democratically elected city council. The chamber was acting like a “supreme city council” and other stakeholders were shut out. Bent Flyvbjerg: Bringing Power to Planning Research Some of the provisions of the original plan were implemented, but without restricting automobile access, which led to an increase in accidents involving bikes and cars. Recognizing the undue influence of the Chamber of Commerce, Flyvbjerg recommends the creation of planning councils representing all stakeholders and interested and affected parties, where dialogue and debate would occur in the open, not behind closed doors. In essence, he says that the Aalborg got warped by the power of the Chamber of Commerce. Interestingly enough, there were different outcomes in Copenhagen, Bogotá, Medellín, and Curitiba.