The Emergence of International Human Rights

advertisement

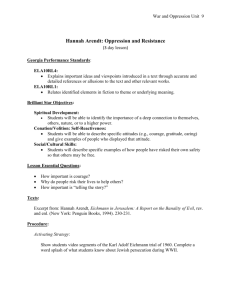

The Emergence of International Human Rights Hersch Lauterpacht - shift of the center of gravity of international law from sovereignty to human rights (1950)? Lauterpacht on mid-twentieth century ethical challenges to IL and human rights… ”the direct subjection of the individual to the rule of IL is an essential condition of the strenghtening of the ethical basis of IL and of its effectiveness in a period of history in which the destructive potentialities of science and the power of the machinery of the State threaten the very existence of civilized life.” Lauterpacht on State Sovereignty and International Human Rights… ”It is the sovereign State, with its claim to exclusive allegiance and its pretensions to exclusive usefulness that interposes itself as an impenetrable barrier between the individual and the greater society of all humanity…the recognition of the individual, by dint of the acknowledgment of his fundamental rights and freedoms, as the ultimate subject of international law, is a challenge to the doctrine which in reserving that quality exclusively to the State tends to a personification of the State as a being distinct from the individuals who compose it, with all that such personification implies…International law, which has excelled in punctilious insistence on the respect owed by one sovereign State to another, henceforth acknowledges the sovereignty of man. For fundamental human rights are rights superior to the law of the sovereign state.” Lauterpacht on Changes in the subjects of IL… ”the recognition of the individual as a subject of international rights, the acknowledgment of the worth of human personality as the result of the denial of fundamental human rights; and the increased attention paid to those already substantial developments in IL in which, notwithstanding the traditional dogma, the individual is in fact treated as a subject of international rights.” Lauterpacht on the paradox of International Human Rights as superior to the law of the State ”There is one objection to the notion of natural rights which, far from invalidating the essential idea of natural rights, is nevertheless in a sense unanswerable. It is a criticism which reveals a close and, indeed, inescapable connexion between the idea of fundamental rights on the one hand and the law of nature and the law of nations on the other. That criticism is to the effect that, in the last resort, such rights are subject to the will of the State: that they may – and must – be regulated, modified, and if need be taken away by legislation and, possibly, by judicial interpretation; that, therefore, these rights are in essence a revocable part of the positive law of a sanctity and permanence no higher than the constitution of the State either as enacted or as interpreted by courts and by subsequent legislation.” Hannah Arendt’s 1950 Critique of International Human Rights Arendt’s Critique of International Human Rights ”No paradox of contemporary politics is filled with a more poignant irony than the discrepancy between the efforts of well-meaning idealists who stubbornly insist on regarding as ”inalienable” those human rights, which are enjoyed only by citizens of the most prosperous and civilized countries, and the situation of the rightless themselves. Their situation has deteriorated just as stubbornly, until the internment camp – prior to the second World War the exception rather than the rule for the stateless – has become the routine solution for the problem of domicile for the ’displaced persons.’” Lauterpacht and Arendt on…Citizen Rights and International Human Rights • Both Lauterpacht and Arendt note the clear and fundamental distinction between the rights of the citizen that dominated modern revolutions and the emergence in mid-twentieth century of ”human rights” proper. • The rights of the citizen is predicated on the construction of spaces of citizenship in which rights were accorded and protected in a particular political community. • Inherent in the notion of human rights is the transcendence of political community, state and nation. The central events picked up by Lauterpacht is the recasting of rights as entitlements that might contradict the sovereign nationstate from above and outside rather than serve as its foundation. Arendt stresses the problems and pitfalls of this project. No break-through of International Human Rights in the 1950s despite of the UDHR • Long into the twentieth century, the link between rights and the nation-state remained relatively untroubled, despite of some early voices to the contrary. • Decolonization struggles NOT Human Rights struggles but quests for national self-determination. The rise of International Human Rights in the 1970s Explanations for the rise of International Human Rights in the 1970s • A move from rights as a politics of the state to the morality of the globe. A move that had failed to materialize in the early- and mid-twentieth century. • Human rights became a moral alternative to bankrupt political utopias. • The last utopia – one that became powerful and prominent because other visions imploded (Moyn). • Human rights are only a particular modern version of the ancient commitment to the cause for justice - The Human Rights movement! The Human Rights Movement ”The international human rights movement is made up of men and women who gather information on rights abuses, lawyers and other who advocate for the protection of rights, medical personnel who specialize in the treatment and care of victims, and the much larger number of persons who support these efforts financially and, often, by such means as circulating human rights information, writing letters, taking part in demonstrations, and forming, joining, and managing rights organizations. They are united by their commitment to promote fundamental human rights for all, everywhere.” (Aryeh Neier) I. Has the positivization of IL and the expansion of human rights institutions overcome the human rights paradox noted by Lauterpacht and Arendt in the 1950s? • Positivization of Human Rights through ICCPR (1976) and ICESCR (1976), European Convention of Human Rights (1953), the American Convention on Human Rights (1978) The African Charter on Humans and People’s Rights (1986) means that the we’ve overcome ”the fundamental and decisive ethical flaw” (Lauterpacht) of the UDHR in placing no duties or obligations on states. II. Has the positivization of IL and contemporary human rights institutions overcome the human rights paradox noted by Lauterpacht and Arendt in the 1950s? • Progressive development of the supranational enforcement of human rights: – UN human rights system (universal applicability) • UN Chater-based bodies such as the Human Rights Council • UN treaty-based bodies such as the Human Rights comittee – Regional arrangements • European Council and Eurpean Court of Human Rights • Inter-American Commission and Court of Human Rights • African Commission and Court on Human and People’s Rights III. Has the positivization of IL and contemporary human rights institutions overcome the human rights paradox noted by Lauterpacht and Arendt in the 1950s? • Even if there are human rights norms binding on states they would appear to be based on the trinity of state-population-territory, and the force of obligation decreases with the distance to each of these determinants. Despite of incessant claims to universality and inalienability of human rights the question of ”jurisdiction” still looms large (Noll). • Human rights must come from within the state. States remain the ultimate power holders, legislators and implementing agents of human rights. Thus, Human Rights disintegrate into a multitute of singular legal obligations, subject to – questions of state responsibility such as if a violation is attributable to a state? – questions of treaty law such as if a state is bound by the specific human rights obligation violated? Are there any valid reservations? Derogations in Emergency situations. Interaction with other state obligations? – Interpretation and application in particular cases by state authorities, – Admissibility and forum considerations, is there a Court or quasi-judicial body in which human rights can be claimed when states fails to properly implement them? IV. Has the positivization of IL and contemporary human rights institutions overcome the human rights paradox noted by Lauterpacht and Arendt in the 1950s? • International Human Rights have Developed Significantly and human rights remain an important – perhaps presently THE call for global justice. • Yet, the paradox remains…Human rights are both always and never universal. The movement assert that fundamental rights belong to everyone, no matter who they are and regardless of context or extenuating circumstance. Yet people can only realize their right by asserting them in particular places and attending to specific contexts of struggle, alliance and conflict. (Stern & Straus 2014) • International Human rights is not the end of history as far as global justice is concerned: an at times promising, yet complex, and unfinished struggle, frought with difficulties and problems. • Not a dissuasion but a plea for the study of international human rights!