Unit 2: “Sources” Assignment

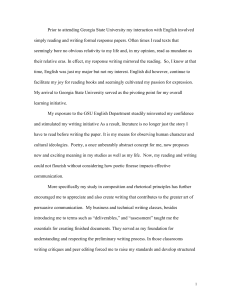

advertisement

RWS 100 @ San Diego State Argument is at the center of SDSU’s GE program and lower division writing program. Why? Because argumentation is central to academic literacy, critical thinking, and civic life - Lasch: “argument is the essence of education… [and] central to democratic culture”; - Norgaard: “Universities are houses of argument.” - Graff: “Argument literacy” is key to higher education. RWS100: MAIN ASSIGNMENTS 1. Unit 1: Analysis of a Single Argument: Describe and analyze an author’s project, argument, claims, support and rhetorical strategies. 2. Unit 2: “Sources” Assignment: Construct an account of an author’s argument; research outside texts and analyze how they extend, complicate, challenge, illustrate, or qualify the argument. 3. Unit 3: Strategies Assignment: Construct an account of one or more authors’ arguments and explain rhetorical strategies that these authors—and by extension other writers—use to engage readers in thinking about their arguments. 4. Unit 4: Optional 4th assignment – “lens assignment,” portfolio, or reflection. The units build on each other, but all begin with 1. The rhetorical situation 2. “PACES” Project Argument Main Claims Evidence Strategies Helping students understand new terms and read rhetorically… To help students understand this new way of approaching texts, we often begin with a series of short, simple texts that are “reflexive,” that foreground their own rhetoric, reflect on their rhetorical situation, reveal their persuasive strategies. Then we ask students to compose short texts and perform a similar task – reflect on the rhetorical situation, the moves they make, the claims they advance, and the strategies they use. Using a YouTube Animation to introduce rhetorical concepts Situation: The syllabus says that the instructor does not accept late work and that if you miss class you will be penalized. Nevertheless, you miss three classes (out of 15 total) and try to hand in the second major assignment a week late. If the instructor doesn’t accept your work you will fail the class. Assignment: Please write the instructor a brief email explaining your situation. You do not want to fail the class. Unit 1: Common Activities 1. Pre-reading and “pre-discussion” work Examining Titles Carefully: Chua’s article “A World on the Edge” is part of her book World on Fire: How Exporting Free Market Democracy Breeds Ethnic Hatred and Global Instability Section Headings you can find out a lot by going through the section and chapter headings. Eg Pinker’s “The Moral Instinct” 1. The Moralization Switch 2. Reasoning & Rationalizing 3. A Universal Morality? 4. The Varieties of Moral Experience 5. The Genealogy of Morals 6. Juggling the Spheres 7. Is Nothing Sacred? 8. Is Morality a Figment ? 9. Doing Better by Knowing Ourselves Unit 1: Common Activities cont. 2. Modeling close reading strategies – annotating, posing questions, reading actively and critically. Unit 1: Common Activities cont. 3. Charting – what is the text doing (what, how, why moves are made). Students chart their own and their peers’ writing Showing that this claim really is in the text, and why E. makes it. An important part of Ehrenreich’s argument is that the poor are invisible to affluent people. She suggests that the affluent “are less and less likely to share public spaces and services with the poor,” that political parties are unwilling to “acknowledge that low-wage work doesn’t lift people out of poverty” (217) and that media attention focuses more on “occasional success stories” than on the rising numbers of poor and hungry people (218). The fact that the poor are invisible contributes to the lack of attention that the problem of low wages is getting. Writer telling reader one piece of E.’s argument, one claim. Explaining why the “invisibility claim” is significant Unit 1: Common Activities cont. 4. PACES (project, argument, claims, evidence, strategies) Identifying claims – a good rule of thumb is to look for the following cues: - question/answer pattern - problem/solution pattern - self-identification (“my point here is that…”) - emphasis/repetition (“it must be stressed that…”) - approval (“Olson makes some important and long overdue amendments to work on …”) - metalanguage that explicitly uses the language of argument (“My argument consists of three main claims. First, that…”) Identifying and sorting claims Unit 1: Common Activities cont. Drafting: models, outlines, templates, rhetorical precis; metadiscourse, quotations 6. Drafting: peer review, workshops, review plans, student “read-alouds,” conferencing 7. Assessment and response 8. Reflection and reflective practice (applying concepts to students own writing – e.g. charting, analyzing students’ moves and strategies, etc.) 5. They Say/I Say Templates – verbs for talking about arguments Templates: The Graff & B Template One of our templates We show students how to be apprentices to the kinds of writing they’re reading in the class. SDSU Student Tyler Stevens: In this paper I will assess O’Brien’s story and Kaldor’s speech, and show how war inevitably affects many more people besides the soldiers that are fighting in it. I will also point out each author’s rhetorical strategies, hoping to distinguish which author is more effective in their argument, and what moral uncertainties are dislodged in their writings. (1) RWS Learning Outcome: Use metadiscourse to signal the project of a paper and guide a reader from one idea to the next. We give students opportunities to reflect on their growth in writing and reading in relation to our learning outcomes. Review and reflect on the four papers you wrote this semester. What are two ways you feel your writing has strengthened? Give specific examples from your papers to illustrate this. How do these strengths add to the overall success of your writing? Discuss how these strengths increased your ability to accomplish one of our chief course outcomes: Construct an account of an argument; translate that argument into your own words. -RWS 100 Final In-Class Writing “The ability to reflect on what is being written seems to be the essence of the difference between able and not so able writers from their initial writing experience onward’ (Pianko, quoted in Yancey, Reflection in the Writing Classroom, p.4)