Hmong New Year Activities in Laos

advertisement

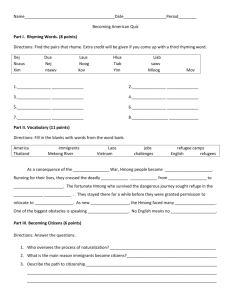

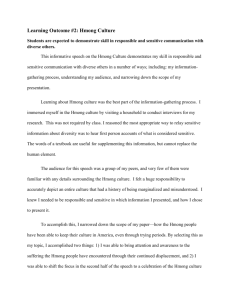

Department of History University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire Shaping Identities for Hmong Americans: An Analysis of the Hmong New Year in Minnesota and Wisconsin By: Panhia Xiong History 489 Research Capstone Professor: Oscar Chamberlain Cooperating Professor: Charles C. Vue Copyright for this work is owned by the author. This digital version is published by McIntyre Library, University of Wisconsin Eau Claire with the consent of the author. December 18, 2014 1 Table of Contents Abstract……..……………………………………………………………………………………..3 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………..4 Historiography…………………………………………………………………………………….5 Hmong New Year: Shamanism and the Festival………………………………………………….7 The Assimilation Theory………………………………………………………………………...10 Hmong New Year Activities in Laos…………………………………………………………….13 Competitions, Pageants, and the Night Party…………………………………………………….16 Language Barriers: Hmong and English…………………………………………………………19 The Traditional Attire……………………………………………………………………………22 A Modern Twist in Clothing…………………………………………………………………......24 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………….27 Appendix………………………………………………………………………………………....31 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………………..35 2 Abstract Hmong Americans have resided in the United States for roughly 40 years after the Vietnam War. Shifting from their original way of life, Hmong Americans began to assimilate into the American lifestyle in order to survive in the new environment. The effect of assimilating Hmong Americans youth have shown some little interest in learning about the Hmong culture. For some others, the knowledge of Hmong culture is minimal knowing only the basic history of the Hmong. This has stimulated a fear amongst the older Hmong who worried that the Hmong culture will cease to exist. Thus, in order to teach the Hmong culture to Hmong American youths and non-Hmong, the older Hmong have relied on the Hmong New Year celebration as a method to maintain their ethnic identity and culture. The remnants of the Hmong culture: language, clothing, and activities are emphasized in the celebration as a way to keep the Hmong culture and history alive. 3 Introduction: The Hmong People and the Vietnam War Initially from China, the Hmong once belonged to the ethnic group known as Miao. To avoid oppression from imperial rule during the Qing dynasty, the Hmong fled the country and migrated southward living in the highlands of Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam. Aware that the climate was similar to that of China, many Hmong populations built villages in the highlands and lived a comfortable life. Some took the occupation of raising livestock as others became merchants and made a living selling herbs, clothes, or lumber. Once the Vietnam War started in the countries of Laos and Vietnam, it affected many of the Hmong as they became allies with the American force. The anti-communist forces United States, South Vietnam, along with the help of the Hmong people were losing heavily against communist Pathet Lao, Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese Armies. After the Fall of Saigon in April of 1975, American troops fled the region as well as high Hmong officers. The Hmong who were left behind fled for their lives aware of the persecution that would come after them for alliancing with the anti-communist forces. Those who stayed were either killed or coerced into the new regime. Near the Thailand border, the large masses of Hmong refugees who crossed the Mekong River were given aid by the Thai government. The establishment of refugee camps housed thousands of Hmong refugees and quickly became overpopulated.1 The growing number of Hmong refugees concerned the Thai government due to the lack of funding to stabilize the camps. This in part also gave way to question the legality of residency of Hmong refugees. A growing number of Hmong resistance groups based in Hmong refugee camps also became a concern for Thailand who wanted to remain neutral.2 Eventually, the inability to support such a 1 The Split Horn, Produced by Taggart Siegel and Jim McSilver, feating Paja Thao and his family (PBS, 2001), accessed December 6, 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5LnvuMyUvfI. 2 Laos Diplomatic Handbook, Ibp Usa, (International Business Publications, 2007), 61, 76, accessed December 6, 2014, http://books.google.com/books?id=LJ8LdXbNzssC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false. 4 huge population called for a closure of camps. On the other side of the globe, the Refugee Act of 1980 was passed in the United States which stated that individuals who were “unable” or “unwilling” to return to his or her home based on the fear of persecution and in search of asylum were granted the option of resettlement.3 Hmong refugees were given the chance to move and start a new life spreading worldwide residing in countries such as China, France, the United States and others who agreed to accept the asylum seekers. In the United States, Hmong Americans migrated to areas in California, Minnesota, and Wisconsin where their families were highly concentrated. Hmong dialects spoken were either White Hmong or Green Hmong/Mong Leng which also signified subgroups based on their clothing to clarify any confusion. To understand the usage of Green Hmong and Mong Leng, some preferred to be identified by Mong Leng based on historical folklore but both share the same dialect and clothing. Hence in most writings, White Hmong and Green Hmong/Mong Leng are recorded with as written. Historiography Scholars who have researched the Hmong people based on their involvement in the Vietnam War looked at their experiences and lifestyle. The guerilla tactics done by Hmong soldiers and their experiences after the war have been recorded in many books describing their military experience and outlook on the war. The extensive research on Hmong soldiers and their role in the war have shed light on their perspective of the event but lacked the understanding of their everyday lifestyle before the war leading some researchers to turn their interest in learning about who the Hmong people are and how they have come to address the social changes of war. Paul and Elaine Lewis, as an example, examined the culture and lifestyle of the Hmong in 3 US Congress, Refugee Act of 1980, 96th Cong., 1. 5 Southeast Asia in the 1980s. In their photographic book called, Peoples of the Golden Triangle, the Lewis’ focused on the minority groups in Thailand taking photographs of the different ethnic groups’ clothing, lifestyle, and ceremonial rituals. Their approach to exploring the lifestyle of those particular minority groups especially the Hmong through vivid photographs allowed for a new perspective on approaching historical artifacts and live subjects. The book has illustrated the Hmong culture post-war and brought forth a new approach on Hmong history which will be further discussed. The Lewis’ exploration of the Hmong culture using photography was similarly approached by researcher Annette Lynch. Focused on gender and identity, Lynch expressed the ideas of assimilation through clothing. Lynch’s use of photography enabled her to capture the transition of the traditional Hmong clothing to a style of modernity that emphasized glitter and sequins arguing that the ideas and opinions of the individuals wearing the clothes were influenced of combining both elements of traditional and modern, thus displaying their dual identity of being both Hmong and an American. An example she presented was the comparison of the traditional, simplistic clothes versus the modern, brightly-patterned Hmong clothes; the modern clothing had glitter and sequin embellishments on tops and bottoms compared to the traditional outfit that lacked these additional aspects. The decision of adding different elements onto the traditional clothing represented a move against the cultural norm assisting a new change for Hmong Americans. Likewise, activities seen and performed at Hmong New Years were adapted. The illegality of obtaining bulls and watching bull fights called for new activities for Hmong and non-Hmong spectators alike to enjoy while immersed themselves in the Hmong culture. Western activities present at Hmong American New Year celebrations were accepted as part of a 6 tournament special along with dance and singing competitions. Gary Yia Lee and Nicholas Tapp both compared Hmong New Year activities celebrated back in Laos to those of the celebrations here in the United States. Lee and Tapp raised valid points that the cultural shift such as items being sold at multiple Hmong New Year celebrations became mass produced for profit purposes losing the meaning of the handiwork and its producer for example.4 This book shed light on the traditional values of the Hmong New Year and compared it to the adaptation of Hmong New Years in the United States detailing the significant changes and the outcomes due to those changes. In Mother of Writing, written by William A. Smalley, Chia Koua Vang, and Gnia Yee Yang, they explored and introduced the writer of the Hmong language Shong Lue Yang. Before the Hmong were able to write their own histories, ethnographers and missionaries have already researched and documented the lives of Hmong people through teaching the Hmong Roman Phonetic Alphabet (RPA). This book differed from other sources because it focused on the life of Shong Lue Yang and how he came to spread the teachings of Pahawh Hmong which is considered the original Hmong written language. Today, both the RPA and Pahawh Hmong are widely used among the Hmong communities. Hmong New Year: Shamanism and the Festival Due to the widespread migration of the Hmong after the Refugee Act of 1980, the lives of the Hmong individuals changed drastically from their original slash-and-burn tactics to obtaining entry-level positions. The daily clothes that were suited for the mild temperature in 4 Gary Yia Lee and Nicholas Tapp, Culture and Customs of the Hmong (Santa Barbara: Greenwood Press, 2010), 184. 7 Laos were substituted for thicker jackets to protect their bodies from the cold Minnesota and Wisconsin seasons of fall and winter. However, what remained the same was the celebration of the Hmong New Year festival. Initially held at the end of the harvest season, Hmong leaders from various villages constructed their own Hmong New Year for the community in celebration of greeting the New Year with luck and prosperity while leaving the old year which may have been unsuccessful or have brought bad luck. The New Year celebration had two significant meanings behind the event. The first aspect of the New Year celebration coincided with the religion, Shamanism. The belief that all objects and individuals have a spirit influenced the way the Hmong perceived the world. If a person clashed with a bad spirit, the spirit could cause the individual to be sick—feeling the loss of his or her soul. “Spirits are appeased through ceremonies that range from simple chants to lengthy rituals, including the sacrifice of animals” therefore Shamans served as important communicators between the spirit and natural world.5 Likewise during the New Year week, spirits are renewed to maintain a good health for the upcoming year as ancestral worship rituals are performed to honor the ancestors. To further elaborate, the ritual took place in the private setting of the home. Sacrificed chickens were used as offerings and eggs were symbolized as the new spirit so everyone who were a part of the immediate family was given an egg. Male head households chanted in front of the ancestral alter burning paper money to honor the ancestors and asked for permission for protection whereas the chanting that took place in front of entry doorways were to ward off bad spirits. To finish the ritual, the cooked chicken were placed in front of the ancestral alter for a period of three days and ten dishes were served each day thus the Hmong saying “30 eat” which became the “Promoting Cultural Sensitivity: A Practical Guide for Tuberculosis Programs That Provide Services to Hmong Persons from Laos,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, last updated September 1, 2012, accessed December 11, 2014, http://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/guidestoolkits/ethnographicguides/hmong/chapters/chapter2.pdf 5 8 connotation for Hmong New Year. Although this varied from family to family, the main idea of eliminating the bad spirits and offering food to the ancestors has remained in Shamanist families.6 Hmong New Year as a public festival allowed families to relax and enjoy the remainder of the year by building social bonds between relatives and friends while creating new relationships. Although the religious aspect of the Hmong New Year have been substituted or dropped for those who do not practice Shamanism, the essence of the festival has remained. This facilitated a new way of celebrating the Hmong New Year for all individuals. Particularly, the festival focused primarily on the ball toss game between young singles Figure 1. After stepping through the archway for good luck, the children posed for a picture. which gave them the opportunity to mingle and potentially find a marriage partner. For older crowds, this was an occasion to exchange information about the latest news, to entertain themselves, or to catch up on each other’s lives ending the year with a positive relaxation. In the United States, the Hmong New Year ensured a similar purpose of tightening social bonds. The long year of work and schooling occupied the lives of Hmong Americans. The exposure of American lifestyle through institutions such as public schools and religious congregations influenced their behaviors in social interactions amongst non-Hmong. Where education was limited to them back in their home country, opportunity to learn English became a 6 Within my immediate family, this usually occurs after the Eau Claire Hmong New Year during the weekend of Thanksgiving. This information was based on my experience as a child along with a quick analysis given by Charles C. Vue, my cooperating professor. 9 tool for their survival and adaptation. As the cold climate altered the way the Hmong used to live, clothing gradually became part of their identity of assimilation. Activities that the Hmong were unfamiliar with enabled the younger generations of Hmong to easily adapt to American society. Thus, the assimilation of Hmong Americans has influenced the way Hmong Americans identify who they are and how they perceive their culture. To analyze this, studying the Hmong New Year celebration will help seek answers and possibly pose new questions to future generations, Hmong and non-Hmong. The Assimilation Theory Initial studies of assimilation was conducted by researchers since pre-19th century to test how immigrants integrated into mainstream society. Called the classical assimilation theory, the theory wanted to test the upward mobility of European immigrants. Assumption that descendants of European immigrants were affected by socioeconomic factors played a key role in determining their upward mobility towards the American middle class.7 During colonial America, British Americans made up the majority of incoming immigrants. As more land became available, an increased number of European immigrants such as Italians, Germans, and Irish to name a few established themselves around the areas. The classical assimilation theory only associated European immigrants because of the related histories they all shared. Researchers Greenman and Xie pointed out that immigration scholars have argued this theory to be inapplicable towards Asian and Latin Americans because of their different experiences and minority status obstructing their entry into the American middle class.8 The factor of race and 7 Emily Greenman and Yu Xie, “Is Assimilation Theory Dead? The Effect of Assimilation on Adolescent Well-Being,” Social Science Research 37, no. 1 (March 2008): 109-137, accessed December 6, 2014, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2390825/. 8 Ibid. 10 ethnicity brought forth a different model known as the racial or ethnic disadvantaged model which focused on blocked pathways immigrants faced towards assimilation. Because institutional racism blocked minorities from being able to be fully assimilated into the mainstream culture critics of this model have argued that the overemphasis on racial and ethnic barriers failed to address the socioeconomic standpoint.9 Similarly, the segmented assimilation model, proposed by Portes and Zhou, theorized the process of immigrant adaptation by analyzing the different paths chosen towards assimilation.10 Some theorists, however, argued that socioeconomic obstacles made it difficult for minorities to move up social class. Fast forward a couple decades and the current approach in understanding assimilation present in the 20th and 21st century is the melting pot theory and multiculturalism. The melting pot theory suggested that individuals who associated with their ethnicities and culture had the ability to be a part of the homogenous culture through amalgamation. Though depicted as a positive approach of understanding diversity, the implications meant that individuals who merged were to lose a part of themselves as part of the blending process. Multiculturalism, on the other hand, was depicted as an understanding of diversity in a tolerant society by allowing ethnic and racial groups to express themselves freely. Though this approach differed from the older models of assimilation, critics have argued that multiculturalism isolates ethnic groups and may pose problems for them to appreciate the new culture.11 Assimilation as an idea is complex in it of itself to understanding the shift of Hmong culture. The assimilation theory seen as a linear 9 Susan K. Brown and Frank D. Bean, “Assimilation Models, Old and New: Explaining a Long-Term Process,” Migration Policy Institute, October 1, 2006, accessed December 12, 2014, http://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/assimilation-models-old-and-new-explaining-long-term-process 10 Alejandro Portes and Min Zhou, ”The New Second Generation: Segmented Assimilation and Its Variants,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 530, Interminority Affairs in the U. S.: Pluralism at the Crossroads (November 1993): 74-96, accessed December 15, 2014, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1047678. 11 Sarah Song, “Multiculturalism,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, September 24, 2010, accessed December 8, 2014, http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/multiculturalism/#CriMul 11 process where the minority gives up cultural values and beliefs from origin of country and accepts those of the host country described the steps in which a minority group proceeded towards full assimilation. 12 As the minority group interacts and resides with individuals who are affiliated with the majority group, they begin to assimilate into that of the dominant society embracing or unconsciously accepting some of the same behaviors and values. The increasing rate of young Hmong-Americans being fully assimilated into American culture has brought some fears among the older generations of Hmong Americans who believed that the Hmong culture will cease to exist.13 An often discussed topic within the Hmong community was the access to education between young Hmong Americans in United States compared to the elders back in Laos. Faruque discovered that younger Americans preferred speaking in English because of their everyday use of the language. The Hmong elders, on the other hand, preferred the Hmong language because it was their native tongue.14 Similarly, scholars understood that the availability of education and the desire to attain an education for Hmong elders prior to resettlement was very low and argued that attending “…English classes were [only] made mandatory for at least heads-of-household.”15 To counter this movement of assimilation, the Hmong have always been an ethnic group even before the diaspora since the time of Ancient China. Comparative to the Jewish, both ethnic groups have sought for ethnic tolerance and independence. Their experiences and histories has allowed them to strengthen the meanings and importance of their respective culture. 12 Cathleen Jo Faruque, Migration of the Hmong to the Midwestern United States (Lanham: University Press of America, Inc., 2002), 16. 13 Ibid, 90-92. 14 Ibid, 90. 15 Bruce Thowpaou Bliatout, Bruce T. Downing, Judy Lewis, and Dao Yang, Handbook for Teaching HmongSpeaking Students (Sacramento: Spilman Printing Company, 1998), 30. 12 The Hmong were highly recognized for their embroidery and story cloths in the late 20th century and have persisted in keeping their culture alive through such crafts. The Hmong who moved to the United States were exposed to American culture where they learned the language, food, societal norms, and such. As they resettled in the United States, Hmong Americans borrowed mainstream ideas and tried connecting it to their own culture and values such as implementing Hmong sports tournaments. Language played a huge role in Hmong society considering that the Hmong relied heavily on oral speaking. In the United States, English became the primary language causing a language barrier between the Hmong youths and the Hmong elders. However, the availability for Hmong language courses along with Hmong story books and dictionaries and the influence of Hmong elders’ insistence on teaching the language for their children has kept the Hmong language alive. In regards to clothing both traditional and western, it signified the individual’s preference. The transformation of clothes in the 21st century drew upon the influences of assimilation and cross cultures, however the significance of clothes as an individual’s uniqueness demonstrated the continuity of identity. Similarly, activities shown at Hmong New Year celebrations were changed as a result of American policies, lack of space and time, and weather climate. Even so, the importance of social bonding and entertainment provided the Hmong a reason to keep the activities active. Though some aspects of the Hmong New Year has changed drastically from the celebrations back in Laos due to indicators of assimilation, some individuals have attempted to resist the changes by reinforcing self-assertion of their own ethnic identity. Hmong New Year Activities in Laos During the New Year celebrations, Hmong would use their time to mingle, watch bull fights, play kataw, compete in the spinning tops game, or ball toss. In the United States, 13 however, sports tournaments became popular activities that were played. Beauty pageants, fashion shows, and dance and singing competitions became more widely known as well. However, the significance of the ball toss game remained somewhat unchanged. The changing activities have allowed for different people to participate leading others to appreciate the adaptive culture yet the changes have lead others to show disappointment of this new culture. Back in the homeland, activities vastly differed from that of the United States. Bull fights were popular among many viewers who came to watch, particularly men. The atmosphere of the crowd cheering and the intense fighting between the bulls were favored by spectators who enjoyed spending their time being entertained without having to worry about work. If people were not watching the bull fights another activity called kataw would be observed. The popular Southeast Asian game was similar to foot volley. The rules were players were to be kept inside a ring or court and the objective was to pass a bamboo woven ball in the air without using their hands.16 The activity was usually played by men and often played as a competitive sport. Though it was played as a leisure sport, many participated in this sport during the New Year to compete with other individuals who came from other areas. Another activity that garnered attention was the spinning tops game also known as ntaus tuj lub. “The top spun vigorously with a long piece of string and then released to knock another’s top over”17 giving the player the upper hand if successful. The game was considered quite challenging due to the skill required to throw the topper accurately as well as keep the topper spinning. Similar to kawtaw, the sport was often played as a leisure activity but were seen at New Year celebrations as well. Another activity played by the Hmong was ball tossing. Initially played by young singles, it allowed for men and women to court each other by singing traditional poetry called kwv txhiaj. 16 17 Gary Yia Lee and Nicholas Tapp, Culture and Customs of Asia (CITY: Greenwood, 2010), 174. Ibid. 14 Kwv txhiaj addressed topics that pertained to the singer’s background or interest such as love, hardships, or being an orphan.18 To emphasize certain aspects of kwv txhiaj, words were stressed by tonal changes. Because of the topics and the exchanging of phrases between the two singers, kwv txhiaj was sung for hours. Partners who were risky made kwv txhiaj more exciting through exchanges of flirtatious verses. If the partner failed to compose a witty verse to combat the other partner, the individual would take off a piece of item from their wardrobe. Nou Xiong explained that during her youth she and her friends heard about a girl who had ball tossed with another boy playing the flirtatious version of the game. The girl was so bad and she didn’t have a lot of clothing that she was almost stripped naked to her undergarments. Ever since then, Nou and her friends wore layers and layers of jewelry and clothing to avoid the same fate.19 Playful and young, Hmong youths enjoyed their time in courting other singles as the Hmong elders took the time to relax. The New Year celebration gave them the opportunity to relax after the long harvest through social interactions and entertainment. Hmong youths socialized with one another to build connections with other young individuals and perhaps court each other. Activities such as kataw, ntaus tuj lub, the ball toss game, and kwv txhiaj displayed how the Hmong used their time to build on these relationships and affirmed their cultural traditions through such activities. In the United States, the hope that these activities remain in such celebrations were desired. But, as the older generations of Hmong realized the difficulty of maintaining these activities, they turned their motive to using the New Year celebration to foster a learning experience for all members of any community. 18 Ibid, 87. Other major themes for kwv txhiaj were wedding songs, funeral songs, loss of home, or parting with a significant other. If there were three singers in total, two females and one male for example, it will be a competition between the two female singers to outwit each other to win the male’s interest. 19 Nou Xiong, interviewed by Panhia Xiong, Eau Claire, WI, November 8, 2014. 15 Competitions, Pageants, and the Night Party In the United States, kataw and ntaus tuj lub became less known within some Hmong youths due to the lack of space to be played and the lack of awareness for the sports. However, some may argue that the two activities were still prominent because Hmong elders brought the games with them since the migrations of 1970s and 1980s. Instead of focusing on how the Hmong used to live, organization members of New Year celebrations have turned their mission to enrich the community about Hmong culture and customs. By doing so, the introduction of western activities have gained attention among younger generations of Hmong Americans due to their exposure from school or television. Western sports such as volleyball and soccer, competitions, and night parties for example have cultivated a new form of Hmong New Year. From a personal survey, participants agreed that many of the New Year celebrations had at least one of the sports or competitions if not more thus demonstrating the high popularity of Western sports at New Year celebrations.20 20 I conducted a survey that asked the participant to check all boxes that applied in regards to the different activities available at New Year celebrations. More than half agreed of seeing or hearing about dance/sing competitions, fashion shows, the ball toss game, and beauty pageants. 16 Popularity for western sports influenced the Hmong community to adapt the New Year activities. By adopting such sports, tournaments have garnered a lot of attention and called for many participants. Soccer became a very popular sport among both genders as more teams participated resulted in prizes being an incentive to keep the teams participating the next year. Volleyball, too, became part a popular sport played by both males and females in Minnesota and Wisconsin with prizes. More recently, flag football emerged as a popular sport over the past decade and has garnered much attention among spectators as well. Aside from the sports activities that took place Figure 2. Men’s soccer tournament at La Crosse Hmong New Year in Wisconsin. during the Hmong New Year, beauty pageants gained spectators from various demographic categories. In the Midwest, Minnesota hosts one of the largest Hmong beauty pageants where females compete to be crowned Miss Hmong and males to be crowned Prince Charming. Similarly, dance and singing competitions have made its way in New Year activities where participants compete in various categories such as ‘traditional’ or ‘modern.’ For Eau Claire’s Hmong American New Year, the competitions have only started about three or four years ago compared to Saint Paul who started the competitions 10-15 years ago. Eau Claire Hmong New Year had two main categories for the competitions: dancing and singing. Those who competed had a chance to win a cash prize up to $300.21 The goal of introducing sports tournaments and talent competitions were to allow Hmong Americans to express their dual identities (Hmong and American) by participating in Western activities while maintain Hmong customs and values. But, Eau Claire Area Hmong Mutual Assistance Association, Inc. “26 Annual Eau Claire Hmong New Year Celebration” http://www.ecahmaa.org/#!hny/c1dnl 21 17 not everyone agreed. New Year attendee Tao Lor argued that the Hmong New Year did not explore the details of Hmong culture such as traditions or religion so the celebration lacked the ability to influence his decision making of forming his own identity.22 On the other hand, other participants from the personal survey argued that the New Year celebration helped reinforced their identity through clothing and language. A new, more ‘liberal’ activity that was introduced to the Hmong New Year festivity was the night party. The organization hired either a Hmong band and/or singer to perform for that evening with music ranging from Hmong pop, folk, or rock to Laotian or Thai songs. Guests were usually younger generations of Hmong Americans but sometimes adults attended as well. Vendors present at night parties sold flowers such as roses and carnations for individuals to give it to their significant other. The night party, a Western influence, has been adopted by the Hmong community to allow for individuals to mingle and have fun, feel young. Hmong night parties have connected American and Hmong culture by introducing the concept of a night party for enjoyment through performances of Hmong, American, and Thai-Laotian music. Activities back in the Thailand, Laos, and Vietnam explored the customs and values the Hmong residents placed importance on. Values such as building relationships were maintained and respected. Traditional activities reinforced their identity and culture in understanding who they were and how they lived. Among Hmong youths, courting played a role in building relationships and reinforced their roles and expectations of creating a family. In the United States, participants of sports tournaments and competitions have also showcased similar feelings which their parents may have felt back in their homeland. Though some respondents in the Wisconsin area had different viewpoints on the significance of the New Year as a method to 22 Tao Lor, online interview by Panhia Xiong, FaceBook, November 26, 2014. 18 understand the Hmong culture, the celebration has certainly exposed values of commitment, entertainment, and social bonding through such activities. Although indications of assimilation such as having Western activities in New Year celebrations, it has shown a heavy influence in the Hmong community influencing members of the community to adapt activities to better parallel the values of Hmong culture. Language Barriers: Hmong and English The Hmong have been dependent on oral histories as a means to communicate and leave their stories for the future Hmong generations for centuries. Earlier ethnographers who studied the Hmong believed that the Hmong lacked a writing system. However, there existed a myth which some have argued that the Hmong writing system was erased during their time of persecution from the Chinese. Pahawh Hmong and the Roman Phonetic Alphabet for the Hmong language surfaced around Laos in the 1950s-1960s. In the early 1960s, the Hmong writing system was developed by a man named Shong Lue Yang who was considered the “mother of writing” and was a son of God who gave Shong Lue Yang the ability to learn how to write Pahawh Hmong and spread the teachings. 23 A decade earlier, Catholic missionaries in Laos created the writing system using the Roman Phonetic Alphabet (RPA) and has been kept since. The two major Hmong dialects spoken in United States is Hmoob Dawb referred in English as White Hmong and Mong Leng or Hmoob Njuas referred in English often as Blue or Green Hmong. 23 William A. Smalley, Chia Koua Vang, and Gnia Yee Yang, Mother of Writing (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990), 16-24. According to the book, Chia Koua Vang and Gnia Yee Yang were disciples of Shong Lue Yang in which they learned about the creation of the writing system and extended the teachings to other Hmong. 19 Hmong, as a language, consists of eight tones which illustrates the rise and fall of the voice used for words. As for vowels, White Hmong have six vowels arranged for the position of the tongue and consists of two nasal vowels and vowel glides. Compared White Hmong to Green Hmong/Mong Leng, when a vowel is present in a word pronounced by White Hmong, a double vowel may be used in Green Hmong/Mong Leng though it does not always account for all vowels.24 For example, the word mother has the vowels (i) and (a). In White Hmong, mother is written as niam. In Green Hmong/Mong Leng, mother is written as nam. Green Hmong/Mong Leng lacks the aspiration sound that White Hmong possesses in their vocabulary but gains a third nasal vowel. In regards to consonants, both White Hmong and Green Hmong/Mong Leng have simple and complex consonants which the Hmong language relies on. Simple consonants are sounds pronounced with the use of lips, uvula, and the throat. For complex consonants, an addition of puff or air is added to create a different sound.25 Shong Lue Yang’s version of the written Hmong language used similar characters to that of Asian cultures such as Vietnam, Thai, and Laotian. The RPA, however, indicated tones with letters and lacked diacritics. Both systems were used and taught in Laos but the RPA has gained more widespread use especially in the United States because of the familiarity of the alphabet in the English language. Education has brought many opportunities for Hmong individuals to learn English and survive in the new environment. However, it has also created language barriers between Hmong youths and Hmong elders. Susan Burt conducted a research surveying 30 participants from Hmong elders ranging from ages 43-88 to Hmong youths from ages 18-25 to study the language shift from Hmong to English by reviewing terminology and meanings of both languages for the phrase ‘thank you’. Her first study was to see how Hmong youths and elders used ‘thank you’ in 24 25 Ibid, 44-45. Ibid, 46. 20 regards to request for something or someone. Her results showed “…the two generations of speakers interviewed do not use these resources in the same way; some of these differences are probably due to the younger generation’s extensive contact with English.”26 Education certainly has influenced the interaction between Hmong youths and elders due to the opportunity to attend schooling. The observation similarly made by Hmong elders of the language shift has influenced their desire to teach their children the Hmong language. The threat of losing the language and inability to effectively communicate has steered their attempt through other means. In Laos, dialects spoken especially during the Hmong New Year celebrations has allowed individuals to understand where others come from. White Hmong were easily distinguished from Green Hmong/Mong Leng due to the different vowels in the language. The witty versus used in kwv txhiaj were not regularly spoken in daily conversations which made kwv txhiaj unique. Hmong elders have understood the phrases tossed between pairs who recited kwv txhiaj in comparison to Hmong youths. Often, the belief that Hmong youths are unappreciative of the lyrical poetry are due to them primarily speaking English and not understanding kwv txhiaj leading Lee and Tapp to agree that the presence of kwv txhiaj at New Year celebrations pointed out the challenges of distinguishing the singer’s background and location of origination losing one significant aspect of the folk song.27 Similarly, movies and DVDs have recently used RPA and English subtitles for every consumer to understand even Hmong. This has allowed 26 Susan M. Burt, The Hmong Language in Wisconsin (Lewiston: Edwen Mellen Press, 2010), 104. As part of a survey I conducted, I had asked the participants to rate their Hmong speaking capabilities. Out of 21 participants who responded, 52% stated they were average Hmong speakers and 29% declared beginners. Similarly, I had asked the participants to rate their English speaking capabilities. Out of 21 participants who responded, 71% declared good speakers and 24% declared native speakers. 27 Gary Yia Lee and Nicholas Tapp, Culture and Customs of Asia (Santa Barbara: Greenwood, 2010), 89. Singers could be distinguished through dialects and dress outfits. However, due to the longevity of residing in the States, some folk singers have mixed different styles making kwv txhiaj more creative and adaptable. 21 merchants to expand their products for everyone. Hmong-dubbed movies have also appeared on shelves to help teach Hmong children learn the language. Mai Kou Xiong noted that, Users of social media can be seen posting photos and updating statuses from the celebration to friends and families far and near…the latest technologies such as ipods, smart phones, and tablets are now an everyday tool which connected New Year goers to the rest of the country, if not the world.28 More importantly, both Hmong youths and elders have used both Hmong and English to communicate with each other. The possibility that the only way to communicate with one another was to meet half way by speaking both languages. This has created a new bridge of communication of mixing both Hmong and English together—Hmonglish. As Hmong elders picked up English from their children’s interaction and social the children has well. This brought forth new perspectives on understanding the history of the people and strategies to adapt themselves as Hmong living in an English speaking world. The Traditional Attire During the Hmong New Year, individuals dressed more luxurious in hope that the individual may find a potential marriage partner. The event also allowed for families to display their wealth and status through the clothes that they wore during the festival. For White Hmong 28 Mai Kou Xiong, “Nyob Zoo Xyoo Tshiab 2013! Celebrating the 2013 MN Hmong New Year,” Hmong Times, December 12, 2012, accessed December 18, 2014, http://www.hmongtimes.com/main.asp?Search=1&ArticleID=4612&SectionID=31&SubSectionID=190&S=1. 22 women, they had two different styles: skirts or pants. For skirts, White Hmong women wore long, black jackets with blue cuffs. A white skirt wrapped over the jacket and covered with a black apron called sev. Next, a red and green sash was used to wrap the waist covering the strings that held the apron. To display the wealth and embroidery skills of that particular family, an embroidered belt decorated with French coins or beads was placed on top of the sashes. The Hmong used French coins as part of their outfits during the time of French occupation in Laos and have remained since. Silver necklaces called sauv “… [symbolized] wealth and the essence of the good life” made by silversmiths.29 To finish the outfit, White Hmong women wore a turban-like headdress made of hemp cloth that had a striped cloth which crossed over the front of the turban. For the pants style, White Hmong women wore the same black jacket with blue cuffs but paired the look with black pants which resembled similarly to the harem pants today. Instead of using one apron like the dress style, two aprons were used to cover the front and the back of the pants and was secured using a red sash in which the tail was exposed from the back and a green sash in which the tails were exposed from the front. Jewelry and headdress were worn the same way as the skirt style. Unlike their counterpart, White Hmong men had a simpler attire. They wore long, black jackets paired with baggy, black pants which were secured with a red sash. The attire was finalized with a one-tiered Hmong silver necklace with a plain black skull cap and a mini pom-pom attached in the center. The White Hmong group emphasized their skill in stitching patterns whereas the Green Hmong/Mong Leng group used the batik style for their clothing. Green Hmong wore black jackets with blue cuffs and had a zigzag stitching in the front. The skirts differed from the White Hmong women by the use of colorful patterns and batik work. Similar to the White Hmong, the 29 Paul Lewis and Elaine Lewis, Peoples of the Golden Triangle: Six Tribes in Thailand (New York: Thames and Hudson, 1998), 116. 23 finish look had an apron, red and green sashes, and paired with jewelry and a headdress. The Green Hmong men had a different style compared to the White Hmong men. Green Hmong men wore black cropped jackets which had embroidered stitching across the chest. Their black dropped-crotch pants were much lower than the White Hmong men. The clothes for everyday wear differed from New Year outfits. Due to the labor-intensive work that the Hmong performed daily, Hmong New Year clothes were much thicker and embellished with coins and beads to show the handiwork and wealth of the wearer. However, the adaptation of clothes has evolved overtime and still plans on doing so. A Modern Twist on Clothing Already aware of the changes the Hmong had to make in order to advance themselves, they were adaptive in their styles of clothing. In the United States, the Hmong were exposed to denim jeans, formal dresses, and different types of shoes eventually constructing a part of their social identity. For some Hmong American females, the New Year clothes combined elements of the Western style such as wearing leggings underneath the Hmong skirt. For men, the droppedcrotch pants were substituted for dress pants because it looked more modern. Respondents of the survey explained that Western clothing were more likely to be worn due to the easy handling of putting it on compared to Hmong clothes which were heavy and thick. Because United States has been expressed as a salad bowl the ideology suggests individuality which some Hmong Americans have embraced their dual identity by piecing different types of styles together for creativity. Annette Lynch described this as “Hmong American, in the midst of cultural change, use dress worn in the New Year as a symbol to express and debate versions of cultural and 24 gender identity.”30 Some have taken the chance to rebel against norms by wearing brightly colored outfits embellished with pompoms or gems. Others have intermix elements from various cultures for purposes such as Figure 2. The resistance to change among the wearers have displayed Figure 3. The little girl belonged to a dancing group who participated in the dance competition in Saint Paul, MN. some kind of appreciation and pride in the decision. Mai Xeng Xiong stated that the traditional outfit appeared more unique than the creations made today because of its originality. “Due to the high demand in new styles and colors, it has become overwhelming and popularized losing its significance.”31 However, some have taken into account the appreciation of Hmong culture. Some designers have modified the traditional Hmong outfit yet kept its originality. According to Hmong American Custom Clothing, designer Kia Vang explained “The vibrant colors and the style of the clothes are a beautiful portrayal of our culture… To wear Hmong Clothes is to directly identify with the Hmong Culture”32 suggesting that their effort in keeping Hmong clothes traditional yet being flexible with the changing interests of consumers are what makes their designs unique. 30 Annette Lynch, Dress, Gender, and Cultural Change: Asian American and African American Rites of Passage (Oxford: Berg, 1999), 33. 31 Mai Xeng Xiong, interview by Panhia Xiong, Eau Claire, WI, December 13, 2014. 32 Kia Vang, online interview by Panhia Xiong, FaceBook, December 15, 2014. Although Kia Vang is the designer for Hmong American Custom Clothing, her daughter helped market her designs on their FaceBook page so she was the mediator but did not identify her name. I referred to their store website to find Kia’s name. 25 For those interested in American clothing, women either dressed formally or casual. For the formal attire, Hmong American females completed their dress with a blazer or a cardigan. For casual look, the wearer wore either a pair of shorts, skirts, or jeans (depending on the weather) with a t-shirt or blouse. For some individuals, wearing a different culture’s traditional clothing was the preference and ranged from the Miao outfit to Indian dresses. One popular style that remained popular among both Hmong youths and elders were Thai-Laotian dress due to its less heavy outfit but intricate design. A factor for this popularity may be due to the parents’ exposure to Thai and Lao culture during their time in the refugee camps or possibly just self-interest. Of course, some Hmong elders Figure 4. This Hmong lady explained that she bought the outfit when she went to Chiang Mai, Thailand and said the outfit was based off of another ethnic group. who believed in the old ways strongly encouraged their children and grandchildren to wear Hmong clothes as a reminder of their identity and culture. Unlike their counterpart, the decision to wear traditional clothes within young Hmong American men has varied. Some have preferred to wear American apparel of a t-shirt, jean, and tennis shoes or more formerly, a dress shirt, dress jacket, and pants with dress shoes. Others have mixed two styles; for example, a man may wear the Hmong jacket but wear denim jeans for the bottom. As people changed so did their perspectives and beliefs. The assimilation process was one of the greatest worries for the Hmong elders because the culture they once knew was evolving. In order to have their children and their grandchildren embrace their history and culture, they have strongly encouraged Hmong American youths to wear Hmong clothes during 26 the festival. Some have resisted the change by attempting to parallel the traditional outfit. Others have taken the opportunity to shape the way Hmong showcase their individuality and creativity through clothes. The evolution of clothes along with the development of Hmong Americans assimilating into mainstream culture has influenced designers, wearers, admirers, onlookers to see the changes the Hmong have gone through and understand a bit more about their values and identity in American society. Conclusion The Hmong have come a long way to establish themselves in the United States like many ethnic groups before them. The outcome of the Vietnam War led them to flee their homeland in search for refuge. With given opportunity from foreign countries, Hmong refugees opted to make a new living in hope that they may live a similar life. Those who determined that the United States was going to be their new homes, they were not ready for the different technologies and available resources such as aid assistance. The process of assimilation into mainstream culture posed some challenges in being accepted by the majority culture and surviving in a new environment foreign to them. As time progressed, their exposure to the American culture and with assistance from others have enabled them to live a comfortable life away from the fear of prosecution. Traditional sports were easily taken over by western activities if not adapted. Hmong families were exposed to parks and recreational sports that it was easier for the children to occupy themselves than be stuck at home playing by themselves. Organization members and their plan to implement western activities held at Hmong New Year celebrations motivated them 27 to use the event to illustrate Hmong culture and customs. The significance of the ball toss game as an “only singles” activity was altered to fit all participants: Hmong and non-Hmong, youths and elders. Kwv txhiaj, on the other hand, fought for its survival in the new world. Where it used to be sung and performed at Hmong New Year celebrations primarily, kwv txhiaj has been transported on DVDs and online streaming sites such as YouTube making it available worldwide. The change from a ‘one performance’ has been recorded for commercial use to be seen numerous times. Mass marketing and commercialization has shown the indicators of assimilation through the values of capitalism among Hmong American merchants. For youths to participate in activities at schools and clubs gave them courage to connect more easily with others through such common interest. Changes in activities from traditional to western activities available at Hmong New Year celebrations opened doors to all community members Hmong or not. Though some have argued that the New Year celebration lacks the true meaning of the Hmong culture, it certainly has shed light on who the Hmong are in the United States. Belonging to a society of oral speakers, the Hmong learned that to be effective communicators in their realm, strong speaking skills were necessary to negotiate, persuade, or influence others. Since many did not have the opportunity to learn how to read and write, many relied on their speaking skills for their survival. Where education was not highly offered back in Thailand, Laos, and Vietnam to the Hmong, the children of Hmong refugees gained the opportunity to learn and communicate in English in the United States. Though it was difficult at first, their long experience of listening to conversations, interaction, and reading allowed them to be fluent in English. The opportunity for Hmong American youths to socialize with others outside of their race and be exposed to the American culture exercised their English skills. Some Hmong elders, however, believed that this new world was separating the family. The loss of 28 speaking Hmong in the home and the constant communication of English shook the very bones of the older generations. But, the constant reminder of their identity as Hmong Americans affected the behaviors of the two generations by understanding that they were Hmong people living in the American society. To address the issue of language barriers, both generations have taken the effort in speaking “Hmonglish” to overcome these barriers and help one another out in clarifying terms or translating them. Clothes also became susceptible to change just as Hmong Americans adapted to American culture. Where traditional clothes were adorned with French coins and vibrant stitching and batik artwork, modern Hmong clothes gained more of an aesthetic appeal giving rise to its popularity. The simplicity of traditional clothes reflected the status, wealth, and craftsmanship of the family. Modern Hmong clothes embellished with glitter and frills reflected gender roles and identity as Lynch suggested. One of the main arguments that many respondents revealed in regards to their decision process for wearing Hmong clothes was the concern of patience and comfort in wearing the outfit. Some stated that the clothes worn for the celebrations allowed others to see the creativity and uniqueness of the wearers’ outfit. Then there existed those who were interested in other culture’s traditional clothes. The various response of why the individual chose the clothes were based on personal preference and convenience of wearing the clothes. Historians and Hmong Americans alike have sought to understand Hmong culture and its representation in the world. While some have resisted the change by reflecting their past experiences, some have taken the chance to adapt, learn, and shape their culture to make it a part of the American culture. Assimilation models such as the melting pot and multiculturalism have explained processes of assimilation for new comers but have raised meaningful critiques in 29 understanding ethnic groups and their development in the United States. Hmong New Year celebrations as a bridge between individualism versus collectivism, traditional versus modern, or young versus old has illustrated the complexity of assimilation for Hmong Americans. As people adapt, so do culture. Hmong Americans and their familiarity with social changes have enabled them to be flexible and adaptable. Just as Hmong New Year celebrations have created an opportunity for the Hmong and the public to understand the Hmong culture, the celebration has provided them an understanding of themselves as Hmong Americans in a globalized world. 30 Appendix Illustrations 1. 2. 3. 4. Archway.……………………………………………...…………………………………..9 Men’s soccer……………………………………………………………………………..17 Girl Dancer……………………………………………………………………………….25 Lady wearing ethnic outfit…………………………………………………………….....26 Survey DEMOGRAPHICS Participant Information: 1. 2. 3. 4. Name (Will not be revealed to others) Age Place of birth Length of residence in US: 5. Have you ever attended any Hmong New Year in the United States? a. Yes b. No LANGUAGE 6. How well do you speak English? a. Native b. Good c. Average d. Beginner e. Not at all 7. How well do you speak Hmong? a. Native b. Good c. Average d. Beginner e. Not at all 8. Which of the following do you often speak at home between you and the elders (parents, grandparents)? a. English b. Hmoob dawb (White Hmong) c. Hmoob ntsuab (Green Hmong) 31 d. Combination of both English and Hmong (White or Green) e. Other, please list. 9. Which of the following do you often speak at home between you and your siblings (if any)? a. English b. Hmoob dawb (White Hmong) c. Hmoob ntsuab (Green Hmong) d. Combination of both English and Hmong (White or Green) e. Other, please list. 10. Which of the following do you often speak outside of the home? a. English b. Hmoob dawb (White Hmong) c. Hmoob njua (green Hmong) d. Combination of both English and Hmong (White or Green) e. Other, please list. CLOTHING 11. What type of attire do you wear to your Hmong American New Year most often? If you have never attended before, what type of attire do you see/hear about the most? I plan to add pictures here, if possible a. Formal Western clothing (EX: suit/tuxedo, khaki pants, button shirt, semi/formal dress, dress shoes) b. Casual Western clothing (EX: t-shirt, jeans, blouse, skirts, boots, tennis shoes, cap) c. Traditional Hmong clothing (EX for women: black jacket, white-collared blouse, white/Green Hmong skirt, black pants, sauv (neckline jewelry), apron, body coins, hat, shoes) (EX for men: jacket, Hmong black pants, sauv (neckline jewelry), colored sashes, body coins, skull cap, shoes) d. Modern Hmong clothing (EX for women: glittered/colored jackets, colored skirts, sauv, colored apron, body coins, hat, shoes) (EX for men: glittered/colored jackets, glittered/colored pants, body coins, sauv, hat, shoes) e. Hmong Chinese (Miao) f. Thai or Laotian dresses g. Other, please list 32 (Please share any information about the decision process that may have influenced you to pick the attire) 12. What type of attire are you encouraged to wear by either your parents, grandparents, or relatives for any Hmong American New Year? a. Formal Western clothing (EX: suit/tuxedo, khaki pants, button shirt, semi/formal dress, dress shoes) b. Casual Western clothing (EX: t-shirt, jeans, blouse, skirts, boots, tennis shoes, cap) c. d. e. f. Hmong clothing Hmong Chinese (Miao) Thai or Laotian dresses Other, please list (Please share any information about the decision process that may have influenced you to pick the attire) 13. What type of attire are you encouraged to wear by your peers for any Hmong American New Year? a. Formal Western clothing b. Casual Western clothing c. Hmong clothing d. Hmong Chinese (Miao) e. Thai or Laotian dresses f. Other, please list (Please share any information about the decision process that may have influenced you to pick the attire) ACTIVITIES 14. What common activities have you seen or heard of at any Hmong American New Year? a. Pov pob (ball toss game) b. Kawtaw (similar to footvolley) c. ntaus tuj lub (spinning tops game) d. fashion shows 15. What kind of competitions have you seen or heard of at any Hmong American New Year? a. Dance competition b. Singing competition 33 c. Sports tournament d. Beauty pageants FOOD 16. Occasionally, what kind of foods do you see and/or have eaten at any Hmong American New Year? a. Traditional Hmong food (sticky rice patties, Hmong herb chicken soup, stewed meat, water) b. Hmong American food and desserts (Chicken/beef/pork/sausage with rice, egg rolls, papaya salad, meat balls, tri-color drinks (nava), bubble tea, etc.) c. American food and desserts (ice cream, hotdogs and burgers, salad, etc.) d. Other, please list VENDORS 17. What kind of market vendors have you seen at any Hmong American New Year? Check all that applies. a. Clothing (Hmong, Chinese, Western, Thai, Lao, etc…) b. Traditional accessories (sauv, earrings, bracelets, hats, caps) c. Toys (dolls, toy guns, figurines) d. Photography e. Food (vendors that specifically sell either vegetables or mangos with pepper) 18. What kind of organization vendors have you seen at any Hmong American New Year? Check all that applies. a. Student organizations b. Institutional organizations (School, hospitals, churches, etc.) c. Insurance (Life, medical, vehicle, house, etc.) d. Other, please list. PERSONAL OPINION 19. In your opinion, what makes the Hmong American New Year significant? Please explain. 20. In your opinion, do you think the Hmong American New Year has evolved over time? Please explain. 21. Does the Hmong American New Year help you understand Hmong culture? Please explain. 22. Does the Hmong American New Year help you understand your own identity? Please explain. 34 Annotated Bibliography Primary Sources Eau Claire Hmong New Year ’95-’96 flier. Accessed at Chippewa Valley Museum on October 20, 2013. The Eau Claire Hmong New Year flier contained one picture and boxed texts to spread awareness for the New Year. This flier was surprisingly simple and rather dull which illuminated the advancement of Photoshop and visual appeal for today’s New Year fliers. Lor, Tao. Online interview by Panhia Xiong. FaceBook.com. November 26, 2014. Tao was one of the respondents to my survey and gladly accepted my invitation for an online interview. Through the exchanges of email, Tao revealed his perspectives on the Hmong New Year and revealed that the event did not influence his decision in shaping his identity and also stated that the event did not provide much information about the Hmong culture. I found this exchange of emails interesting because his answers described the somewhat unsuccessful outcome the goals of the New Year were trying to obtain. Moua, Houa. Interviewed by Tim Plaff. Eau Claire, Wisconsin. Chippewa Valley Museum. Tape recording. Transcript located in Hmong in America, Houa Moua folder. Accessed on October 23, 2013. Tim’s interview with Houa Moua was to see the changes in Houa’s experience as a teenage girl to a mother during her experiences living in Laos. The interview focused on her experiences as a bachelorette, the war, gender roles, and the Hmong New Year. Houa’s statement about Hmong New Years as a time for social bonding and courtship supported my understanding of how the celebration valued relationships. Moua, Yong Kay. Interviewed by Tim Plaff on November 16, 1992. Eau Claire, WI. Chippewa Valley Museum. Tape recording. Transcript located in Hmong in America, Yong Kay Moua folder. Accessed on October 23, 2014. Yong Kay Moua is the husband of Houa Moua and his interview was primarily focused on the Vietnam War and his experiences with working for the military force. His insight on the war from his perspectives parallel similarly to stories I have heard of from my grandparents so it was interesting to see the resemblance. Vang, Xia; Kha Vang (Lor); Bao Vang (Lor). Interview by Tim Plaff. Eau Claire, Wisconson. Tape recording. Eau Claire Hmong Mutual Assistance Association, January 19, 1993. Accessed October 23, 2013. For this interview, Plaff asked the three Hmong women to look at a series of images and interpret them. He wanted to understand what the image captured and to see if Xia, Kha, and Bao had similar experiences or to find a correlation between the interviewees and the 35 images taken prior to the war. Though this interview was much broader, it did highlight some important characteristics of gender roles and social structure. Xiong, Mai Xeng. Interviewed by Panhia Xiong. Eau Claire, WI. December 13, 2014. Mai Xeng’s perspective on the traditional clothing was interesting because not only did she see how powerful the influence of modern clothes were in the Hmong community but she wanted to go against the ‘norm’ by dressing back to the traditional look of New Year outfits. Her response supported my understanding of how some Hmong Americans are trying to resist small indicators of assimilation. Secondary Sources Burt, Susan Meredith. The Hmong Language in Wisconsin. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Publishers, 2010. This book was very insightful in drawing comparisons between the Hmong elders and the youth in regards to language usage. Burt’s research study of understanding how the two generations interacted with one another as well explaining the challenges both generations faced illuminated the obstacles of the Hmong language surviving in the United States. I relied on this source to help me understand the methods of communication between generations and the obstacles of the language in the United States. Cha, Ya Po. An Introduction to Hmong Culture. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2010. Ya Po Cha explained the Hmong culture by evaluating the ceremonies and rituals performed by Shamans. He also elaborated on customs, traditions, politics, and values of the Hmong. His mention of the Hmong New Year was helpful in understanding the ceremonies and significance the celebration. This book was helpful in understanding the broad picture of Hmong history and culture. Chiu, Monica , Mark Edward Pfeifer, and Kou Yang. Diversity in Diaspora: Hmong Americans in the Twenty-First Century. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2013. Chiu, Pfeifer, and Yang discussed the effects of the Hmong diaspora and how it as changed the way Hmong Americans adapt to the culture. Analyzing poverty, education, and gender roles were some of the topics discussed. I referred to this book as a backdrop of understanding the social issues related to identity. Faderman, Lillian. I Begin My Life All Over. Boston: Beacon Press, 1998. This book explored the lives of 36 strangers living in a foreign land. Participants described the conditions and challenges of being immigrants in the United States. The book was helpful in paralleling the experiences between the Hmong immigrants. 36 Kohler, John M. Hmong Art: Tradition and Change. Sheboygan, WI: John Michael Kohler Arts Center, 1986. Accessed at Chippewa Valley Museum on October 10, 2013. Hmong Art looked at the textiles, jewelry, and musical instruments of the Hmong culture and contained articles and dissertations of Hmong arts. Kohler also relied on imagery to support the changes. This book was helpful in displaying the traditional arts with modern aspects. Lee, Gary Yia and Nicholas Tapp. Culture and Customs of the Hmong. Santa Barbara: Greenwood, 2010. Lee and Tapp’s overview of the Hmong culture and customs were formatted to fit into this book ranging from wedding rituals to Hmong New Year celebrations. They also discussed the lifestyle of the Hmong people as well as their social structure. I used this book as backdrop of generalizing my understanding of the culture. Lewis, Paul and Elaine Lewis. Peoples of the Golden Triangle: Six Tribes in Thailand. London: Thames and Hudson, 1984. This illustrative book shed light on the different types of ethnic groups in Thailand through imagery. The Lewis’ took photos on their musical instruments, clothing, jewelry, and their daily activities which pertained either rituals or farming tactics. Peoples of the Golden Triangle clarified and illustrated many questions I had about the traditional appearances of the materials my grandparents used to know. Looking Back, Stepping Forward: The Hmong People. Produced by D.C. Everest Area Schools. D.C. Everest Area Schools wrote this book for the community to understand about Hmong people and their history. The book also described the social changes they went through as they settled in Wausau, WI. I enjoyed this book because the book contained various statements from the individuals living in Wausau and described the challenges and excitements they faced. Millet, Sandra. The Peoples: The Hmong of Southeast Asia. Minneapolis: Lerner Publications Company, 2002. Millet’s layout of the book was very eye catching and easy to read because it seemed to be used as a cultural guide for teachers and learners. The book provided a general sense of who the Hmong people were addressing their clothing, music, daily activities, language, and struggles. This book was helpful in reaffirming the generalizations about the Hmong people prior to resettlement. Lynch, Annette. Dress, Gender and Cultural Change. Oxford: Berg Publishers, 1999. 37 Annette Lynch provided a different approach of analyzing gender roles and coming-ofage practices by researching the significance of clothes worn in special occasions. She specially looked at Hmong and African Americans to draw the parallels between both groups. Lynch’s research on clothes as an identity definitely benefitted me in understanding how clothes were used as a form of rebellion or reaffirmation of the wearer’s beliefs. Mote, Sue Murphy. Hmong and American: Stories of Transition to a Strange Land. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2004. Sue’s Hmong and American book looked at the lives of 12 Hmong refugees who all contained different backgrounds but shared one experience and that was the Vietnam War. Her interest in capturing the stories of the Hmong refugees to describe their adaptation to American society was influence by her desire to preserve their history. This book drew parallels to the arguments I made about Hmong elders and their worries for adapting to the new society. Pickford, Joel. Foreword by Kao Kalia Yang. Soul Calling: A Photographic Journey through the Hmong Diaspora. Berkeley: Heyday, 2012. Pickford’s photographic book captured the emotions of the third wave of Hmong immigrants in the early 2000s. Along with some captions and analysis, Pickford’s ability to show the comparison between the new Hmong immigrants and the older Hmong who have settled already illustrated the possible outcomes the new Hmong immigrants were going to face. I enjoyed the imagery because the photos contrasted the same group of people but with different experiences. Smalley, William A., Chia Koua Vang, and Gnia Yee Yang. Mother of Writing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990. Writers of this book focused on Shong Lue Yang who was known for spreading the teachings of Pahawh Hmong which is considered to be the original writing for the Hmong language. Mother of Writing specifically focused on Shong Lue Yang’s background, the format of the Hmong language, and the usage. This book was helpful in explaining Hmong in oral and written forms. Thao, Yer J. Foreword by Lourdes Arguelles. Afterword by Marianne Pennekamp. The Mong Oral Tradition. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2006. This book described the significance of oral history in the Hmong culture by evaluating their language usage in comparison to English after the Vietnam War. This book was helpful because the authors of this book referred to the writings of Green Hmong/Mong Leng so it was a different perspective from White Hmong. 38 Vang, Chia Youyee Hmong in Minnesota. Foreword by Bill Holm. Saint Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2008. Accessed at Chippewa Valley Museum on October 10, 2013. Chia Youyee Vang’s book focused on the lives of Hmong refugees living in Minnesota by exploring their experiences. He studied the effects of the war and how the Hmong in Minnesota have adapted to living in the cold weather different from their homeland. Since this book was closely related to the area of my research, I used it to help me develop the understanding of the socioeconomic changes and assimilation process. Yang, Kou. "An Assessment of the Hmong American New Year and Its Implications for Hmong-American Culture." Hmong Studies Journal 8 (2007): 1-32. Kou Yang is a professor who has written many articles in relation to the Hmong people and the social changes that have occurred. In this article, Yang analyzed the Hmong New Year by looking at the presences of technology, marketing strategies, as well as political advertising to show how the Hmong culture has evolved to fit with the American culture. This article was the basis for my capstone by addressing the social changes that occurred within the Hmong community. 39