Direction Fields

advertisement

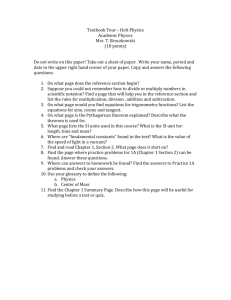

Math 220, Differential Equations

• Professor Charles S.C. Lin

• Office: 528 SEO, Phone: 413-3741

• Office Hours: MWF 2:00 p.m. & by

appointments

• E-mail address: cslin@uic.edu

1

Teaching Assistant

•

•

•

•

•

Mr. Diego Dominici

Office: 607 SEO

Office Hours: ?

Phone: 996-4814

e-mail: ddomin1@uic.edu

2

Please check:

• www.math.uic.edu/~berger/M220/index.ht

ml for Syllabus, assignments, etc...

• www.awlonline.com/nagle for interactive

CD

3

Differential Equation:

Classifications

• Ordinary differential equations, order!

• Partial differential equations

• Linear equations: i.e. linear in the dependent

variable(s).

• Nonlinear differential equations: not linear

• For example: xy" y ' xy 0

This eq. appears in stress analysis,

aerodynami cs.

4

Explicit solution and Implicit solution

• If a function satisfies a differential equation, for

example:

3

y x 8 , satisfy th e D.E.

dy 3 x 2

which can be verified easily.

dx 2 y

• Such a function, defined explicitly as a function

of independent variable x is called an explicit

solution. On the other hand, the equation

x y e xy 0, satisfies the D.E.

5

Given by

• the following:

(*)

• The equation

dy

(1 ye xy )

.

xy

dx

(1 xe )

x ye 0

xy

• is said to defined an implicit solution of the

equation (*) above.

6

In fact, there are many solutions to a D.E

such as (*) above.

• To find a solution passing through a specific point

in xy-plane, we need to impose a condition,

known as : initial value, i.e. y(x0) = y0. This is

known as the initial value problem. We shall

assume that the function f(x,y) is sufficiently

smooth, that a solution always exists. Namely:

• Theorem (Existence and uniqueness): The I.V.P.

y' f ( x, y) , y( x0 ) y0

• always has a unique solution in a rectangle

containing the point (x0, y0), if f and f x are

continuous there.

7

Direction Fields

• Consider the first order D. E.

dy

f ( x, y)

dx

• the equation specifies a slope at each point

in the xy-plane where f is defined.

• It gives the direction that a solution to the

equation must have at each point.

8

A plot of short line segments

drawn at various points in the xyplane showing the slope of the

solution curve this is called a “

direction field ” for the

differential equation.

• The direction field gives us the “ flow of

solutions ”.

9

Example

• For the equation

dy

x 2 y.

dx

•

•

•

•

Using Maple

with(DEtools);

eq:=diff(y(t),t)=t^2-y(t);

DEplot(eq,y(t),t=-5..5,y=-5..5,arrows=slim)

10

Using Maple program, we have

the following

• graph:

11

Another example:

• Consider the logistic equation for the

population of a certain species:

dp

3 p 2 p 2 , with p(0) 2 .

dt

•

•

•

•

using maple, we write in commands:

eq:=diff(p(t),t)=3*p(t)-2*p(t)^2;

DEplot(eq,p(t), t=0..5,p=0..5,arrows=slim);

and get

12

Its direction field

• like this:

13

The Method of Isoclines

• Consider the differential equation

• (*)

dy/dx = f(x,y).

• The set of points in the xy-plane where all

the solutions have the same slope dy/dx;

i.e. the level curves for the function f(x,y)

are called the isoclines for the D. E. (*).

• This is the family of curves f(x,y) = C.

• This gives us a way to draw direction field.

14

Example

• For the differential equation

•

•

•

•

y' x y

f(x,y) = x + y, and the set of points where:

x + y = c, are straight lines with slope (-1).

We can now draw the isoclines for the D. E.

and the solution passing through a given

initial point can also be drawn.

15

Let us graph the isoclines of

f(x,y) = x + y.

• and compare it to the direction field of it, we

see

16

Maple example

• Let us consider the IVP for y’ = x^2 - y,

with three sets of initial points: [0,-1], [0,0]

and [0,2]. What will be the corresponding

solutions?

17

Separable Equation

• Given a differential equation

dy

f ( x, y)

dx

• If the function f(x,y) can be written as a

product of two functions g(x) and h(y), i.e.

• f(x,y) = g(x) h(y), then the differential eq. is

called separable.

18

Example

• The equation

dy 3x xy

2

dx

1 y

• is separable, since

3 y

3x xy

2 ( x )

2 g ( x ) h( y )

1 y

1 y

19

Method for solving separable

equation

• Separable equation can be solved easily,

• Rewrite the equation:

dy

g ( x ) h ( y ) in the form

dx

dy

g ( x ) dx then find

h( y )

antiderivatives on both sides. i. e.

dy

h( y ) g ( x ) dx C.

20

Example

• Consider the initial value problem

dy

y 1

dx

x3

y ( 1) 0

21

Using Maple:

• we can solve the IVP with the following

Maple commands.

• ODE:=diff(y(x),x)=(y(x)-1)/(x-3);

• IC:=y(-1)=0;

• IVP:={ODE,IC};

• GSOLN:=dsolve(ODE,y(x));

• Then use the IC to find the arbitrary

constant.

22

Linear Equations

• We shall study how one can solve a first order

linear differential equation of the form:

dy

a1 ( x ) a0 ( x ) y b( x ),

dx

• We first rewrite the above equation in the so

called “standard form”:

y ' P( x ) y Q( x ).

23

Integration Factor

• Suppose we multiply a function (x) to the

above equation, we get:

( x) y' ( x) P( x) y ( x)Q( x)

• Is it possible for us to find (x) such that the

left hand side

• ?

d

LHS

[ ( x) y]

dx

24

• Since

d

dy

[ ( x ) y ] ( x ) '( x ) y

dx

dx

• We see that this can be done, if

' ( x ) ( x ) P( x ), which implies

d

P( x )dx , by integration, we get

ln| ( x )| P( x )dx. Hence

( x) e

P ( x ) dx

.

25

In this case,

• we can solve it by integration.

• Note that:

[ ( x ) y ]' ( x )Q( x ), implies

( x ) y ( x )Q( x )dx c, consequently

we have

1

y( x)

( x)

( x)Q( x)dx c.

26

Examples:

• Consider the D.E.

y ' y e .

3x

• Solution:

• Another example: solve the following initial

value problem:

dx

3

2

t

3t x t , x (2) 0.

dt

27

Application: Mixing Problems

(Compartmental Analysis)

• Consider a large tank holding 1000 L of water

into which a brine solution of salt begins to flow

at a constant rate of 6 L/min. The solution inside

the tank is kept well stirred and is flowing out of

the tank at a rate of 6 L/min. If the concentration

of salt in the brine entering the tank is 1 kg/L,

determine when the concentration of salt in the

tank will reach 0.5 kg/L

28

• Let x(t) be the mass of salt in the tank at

time t. The rate at which salt enters the tank

is equal to “input rate - output rate”. Thus

dx

x(t )

(6 l / min)( 1kg / l ) (6 l / min)(

kg / l )

dt

1000

or we have :

dx

3x

6

, with x(0) 0

dt

500

29

The equation is separable

• We can solve it easily, using the initial

condition, we get

x (t ) 1000(1 e

3t

500

). Thus, the concentration

of salt in the tank at time t is:

3t

x (t )

1

500

1 e

kg / L. When will this =

?

1000

2

3t

1

500

Set 1 e

, we find t = 115.52 min.

2

30

Existence and Uniqueness

Theorem

• Suppose P(x) and Q(x) are continuous on

the interval (a,b) that contains the point x0.

Then the initial value problem:

• y + P(x)y = Q(x), y(x0)=y0

• for any given y0.

• has a unique solution on (a,b).

31

Application to Population

Growth

• If we assume that the growth rate of a population is

proportional to the population present, then it leads

to a D.E.:

• Let p(t) be the population at time t. Let k > 0 be

the proportionality constant for the growth rate and

let p0 be the population at time t = 0. Then a

• mathematical model for a population could be:

dp

kp,

dt

p( 0) p0

32

This can be solved easily.

• Example: In 1790 the population of the

United States was 3.93 million, and in 1890

it was 62.95 million. Estimate the U.S.

population as a function of time.

33

Application to Newtonian Mechanics

• The study of motion of objects and the effect of

forces acting on those objects is called Mechanics.

A model for Newtonian mechanics is based on

Newton’s laws of motion: Let us consider an

example: An object of mass m is given an initial

velocity of v0 and allowed to fall under the

influence of gravity. Assuming the gravitational

force is constant and the force due to air resistance

is proportional to the velocity of the object .

Determine the equation of motion for this object.

34

Solution

• Since the total force acting on the object is

• F = FG - FA = mg - k v(t). And according to

Newton’s 2nd law of motion, F = m a, we see

that

•

m a = mg - k v.

• Let x(t) be the position function of the object at

time t, and

•

v(t) = dx/dt, a = dv/dt.

35

Equation of motion can be

rewritten as:

• The following separable initial value problem.

dv

k

g

v,

dt

m

v (0) v0 , where

• We can solve the equation easily, and obtain:

mg

mg

v(t )

(v0

)e

k

k

kt

m

.

36

Now, to find the position function

x(t)

• Suppose that at t = 0, the object is x0 units

above the ground, i.e. x(0) = x0 . Then for

the position function x(t), we have the

following I.V.P.

dx mg

mg

(v0

)e

dt

k

k

kt

m

, with x(0) x0 .

• This can be solved easily.

37

We obtain:

• The equation of motion:

kt

m

mgt m

mg

x(t )

(v0 )(1 e ) x0 .

k

k

k

38

Linear Differential Operators (4.2)

• We shall now consider linear 2nd order

equations of the form:

2

d y

dy

(*) a2 ( x) 2 a1 ( x)

a0 ( x) y b( x),

dx

dx

Where ai ( x), and b( x) are continuous in x on

some interval I. We generally assume that a2 ( x)

is never zero on I, thus (*) can be put in the form

d2y

dy

()

p ( x)

q ( x) y g ( x),

2

dx

dx

The so called " Standard form".

39

Homogeneous equation

associated with ()

• is the equation

2

d y

dy

p ( x) q ( x) y 0,

2

dx

dx

in the sence of " linear algebra". For simplicity

we shall define L[y] LHS of this equation, i.e.

L[y] : y" p(x)y' q(x)y .

L is called a differenti al operator of order 2.

40

Remark on linearity of the operator L,

and linear combinations of solutions to

homogeneous equation.

• We have L[y1+y2]= L[ y1]+ L[y2],

• for any constants and , and any twice

differentiable functions y1 and y2 .

• Theroem1. If y1 and y2 are solutions of the

homogeneous equation

• (HE): y+py+qy=0, then any linear

combination y1+y2 of y1 and y2 is also a

solution of (HE).

41

Consider an example

• L[y] = y + 4y + 3y, We use the

convention Dy = y , D2y = y , Dny = y(n) ,

• and rewrite L[y] = D2y + 4Dy +3y, or

symbolically, L = D2 + 4D +3. Since

formerly D2 + 4D +3 = (D + 3)(D + 1), we

see that:

• L[y] = (D + 3)(D + 1)[y]. The solutions for

• L[y] = 0 are y1 = e-x , and y2 = e -3x.

42

Existence and Uniqueness of 2nd

order equation

• Theorem 2. Let p(x), q(x) and g(x) be

continuous on an interval (a,b), and x0 (a,b).

Then the I.V.P.

y" p( x) y ' q( x) y g ( x) ;

y ( x0 ) y0 , y ' ( x0 ) y1 ,

has a unique solution on the whole interval

(a, b) for any choice of the initial values

y0 and y1 .

43

Fundamental Solutions of

Homogeneous Equations

• Let us first define the notion of the Wronskian of

two differentiable functions y1 and y2. The

function

W [ y1 , y2 ]( x) : y1 ( x) y2 ' ( x) y1 ' ( x) y2 ( x)

is called the Wronskian of y1 and y2 .

(in honor of H. Wronski, 1778 - 1853).

Remark : this can be viewed as a 2x2

determinan t.

44

Fundamental solution set

• A pair of solutions [y1, y2] of L[y] = 0, on (a,b)

where L[y] = y+py+qy is called a fundamental

solution set, if W[y1, y2](x0) 0 for some x0

(a,b) . A simple example: Consider

• L[y] = y+9y. It is easily checked that y1 = cos 3x

and y2 = sin 3x are solutions of L[y] = 0. Since the

corresponding Wronskian W[y1, y2](x) = 3 0 ,

thus {cos 3x, sin 3x} forms a fundamental solution

set to the homogenenous eq: y + 9y = 0. We see

that any linear combination c1 y1 + c2 y2 also

satisfies L[y] = 0. This is known as a general 45

solution

Linear Independence, Fundamental

set and Wronskian

• Theorem. Let y1 and y2 be solutions to the equation

y + py + qy = 0 on (a,b). Then the following

statements are equivalent:

• (A) {y1, y2} is a fundamental solution set on (a,b).

• (B) y1 and y2 are linearly independent on (a,b).

• (C) The W[y1, y2](x) is never zero on (a,b).

• For the proof, we need some linear algebra, i.e.

• Linearly dependent vectors,uniqueness theorem

46

etc...

Reminder

• First Hour Exam:

• Date: June 15 (Friday)

• Room: TBA

47

Homogeneous Linear Equations

With Constant Coefficients

•

•

•

•

•

Recall: For equations of the form

ay + by + cy = 0,

by subsituting y = e r x, we obtain the

auxiliary eq: ar2 + br + c = 0. If r1 and r2

are two distinct roots, then a general solution is

of the form y = c1exp(r1x)+ c2exp(r2x), where

c1 and c2 are arbitrary constants.

48

Repeated Roots

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

If in the above equation, r1 = r2 = r, then a

general solution is of the form

y = c1exp(rx) + c2x exp(rx),

Example: consider the D.E. : y + 4y´ + 4 = 0.

Its auxiliary equation is: r2 + 4r + 4 = 0, hence

r = -2 is a double root, the general solution is

y = c1e -2x + c2x e -2x,

49

Cauchy-Euler Equations

• If an equation is of the form:

ax2y + bxy´ + cy = h(x), a, b, c are constants,

then by letting x = e t, we transform the original

equation into:(with t as the independent

variable), ay + (b-a)y´ + cy = h(e t). An

equation with constant coefficients. Hence can

be solved by the method of constant

coefficients. The equation above is known as a

Cauchy-Euler Equation.

50

Reduction of order

• We know ,in general, a second order linear

differential equation has two linearly independent

solutions. If we already have one solution, how can

we find the other one?

• Let f(x) be a solution to y + p(x)y´ + q(x)y = 0.

• We will try to find another solution of the form

• y(x) = v(x)f(x), with v(x) a non-constant function.

• Formerly, we have y ´ = v´f + vf ´, and y = …

• set w = v ´, etc…, we obtain a separable eq. in w.

51

• Finally find v from w by integration.

Example

•

•

•

•

•

•

Given f(x) = x-1 is a solution to

x2 y - 2xy´ -4y = 0, x > 0;

find a second linearly independent solution.

First write the D.E. in standard form.

Next compute v.

Finally, 2nd independent solution is y = v f.

52

Auxiliary Eq. With Complex Roots

• If the auxiliary equation of a linear 2nd order D.

E. with constant coefficents: ar2 + br + c = 0,

has complex roots, (when b2 - 4ac < 0 ). i.e.

• r1 = + i and r2 = - i, where and are

real numbers, then the solutions are

• y1 = e ( + i)x , and y2 = e ( - i)x. Since we know

that e i x = cos x + i sin x , we simply take

• y1 = e x cos x , and y2 = e x sin x as the

two linearly independent solutions.

53

And the general solution is of the

form

• y(x) = c1 e x cos x + c2 e x sin x, where

c1 and c2 are arbitrary constants.

• Remark about complex solution:

• z(x) = u(x) + iv(x) to L[z] = 0 and the fact

that in this case, we also have L[u] = 0 and

L[v] = 0. Thus the real part and the

imaginary part of a complex solution to

L[y] = 0 are also solutions of L[y] = 0.

54

Example

• Consider the D.E.

z"6 z '10 z 0. Clearly th e auxiliary

equation is : r 2 6r 10 0. Since

b 4ac (6) 4(1)(10) 4 0, we see

2

2

6 4

that the roots are r

3 i.

2

3x

3x

Hence y1 e cos x, and y 2 e sin x. and

the general solution is y c1e cos x c2 e sin x.

3x

3x

55

Nonhomogeneous Equation And the

the method of Superposition

• Let L be a linear operator of 2nd order, i.e.

L= D2 + pD + q, and g 0. The equation:

• L[y] = g, is called a Nonhomogeneous eq.

• We wish to solve the equation L[y] = g ,

using a particular solution to L[y] = g , and

a fundamental solution set to L[y] = 0. First

let me introduce the concept of the method

of superposition.

56

Theorem: Let y1 be a solution to the

equation L[y] = g1, and let y2 be a

solution to the equation L[y] = g2,

where g1 and g2 are two functions.

Then for any two constants c1 and c2,

the linear combination c1 y1 + c2 y2

is a solution to the equation

L[y] = c1 g1 + c2 g2 . (This is known as

the Superposition principle).

57

Proof

58

Representation Theorem of L[y] = g.

• Theorem: Let yp(x) be a particular solution to the

nonhomogeneous equation (*) L[y] = g(x),

where L[y]= y + p(x) y + q(x) y , on the

interval (a,b) and let y1(x) and y2(x) be a

fundamental solution set of L[y] = 0 on the

interval (a,b). Then every solution of (*) can be

written in the form

• (**) y(x) = yp(x) + c1 y1(x) +c2 y2(x) . This is

known as the general solution to (*).

59

Example

• Given that yp(x) = x2 is a particular solution

of the equation:

• (*)

y - y = 2 - x2,

• find a general solution of (*).

• Note the auxiliary equation is r 2 - 1 = 0. It

follows that a general solution of (*) is of

the form y = x2 + c1e-x + c2e x.

60

Superposition Principle & the

Method of Undetermined

coefficients.

• Example: Find a general solution to the D.E.

y"3y x e .

2

x

• Step 1: We first consider the associated

homogenous equation:

y"3 y 0

61

Step 2: Find particular solution to

the Non-homogenous equation

using the Superposition Principle

• There are “2” equations:

y"3 y x

2

y"3 y e .

x

62

To find a particular solution to

each of the above equations

• We use the method of undetermined

coefficients, that is: for the first equation, we try

yp = ax2 + bx + c, and

• For the second equation, we try yp = Aex.

• If any term in the trial expression for yp is a

solution to the corresponding homogeneous

equation, then we replace yp by x yp, etc…. See

table 4.1 on Page 208 of your book.

63

Next we present a more general

method, known as:

• The method of variation of parameters,

64

The Method of Variation of

Parameters

• Consider the non-homogenous linear second

order differential equation :

y" p( x ) y ' q ( x ) y g ( x ). ..........(1)

Let { y1 ( x ), y2 ( x )} be a fundamental solution

set for the corresponding homogeneous equation

y" p( x ) y ' q ( x ) y 0. We try particular solution

of the equation (1) in the form:

y p v1 ( x ) y1 ( x ) v2 ( x ) y2 ( x ).

65

Where v1 and v2 are functions to

be determined. We obtain:

• two equations (by avoiding 2nd order derivatives

for the unknows and from L[yp]=g):

v1 ' y1 v2 ' y2 0, and

v1 ' y1 ' v2 ' y2 ' g. solving these two

equations simultaneuously, we get

g ( x ) y2 ( x )

g ( x ) y1 ( x )

v1 '( x )

, v2 '( x )

.

W[ y1 , y2 ]( x )

W[ y1 , y2 ]( x )

66

Where v1 and v2 are functions to

be determined. We obtain:

• two equations (by avoiding 2nd order derivatives

for the unknows and from L[yp]=g):

v1 ' y1 v2 ' y2 0, and

v1 ' y1 ' v2 ' y2 ' g. solving these two

equations simultaneuously, we get

g ( x ) y2 ( x )

g ( x ) y1 ( x )

v1 '( x )

, v2 '( x )

.

W[ y1 , y2 ]( x )

W[ y1 , y2 ]( x )

67

Finally, solution is found by

integration.

• Example:

Find a general solution t o the D.E.

y"4 y '4 y e

2 x

ln x .

68

69