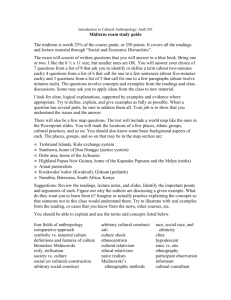

Kinship Terms

advertisement

The Ju/’hoansi peoples By: Mohammed.I, Tariq, Amiin, and Osman How Ju/’hoansi communicate with a verbal language of a limited set of sounds • The Jul’hoan or southeastern Xuun, is the southern variety of the Kung dialect continuum spoken by about 30,000 people in the northeast of Namibia, and by another 5,000 in northwest district of Botswana, specifically the Kalahari Desert. • The smallest unit of sound that can be altered to change the meaning of a word is called a phoneme. In English for example, the words win, pin, kin, and sin all have different meanings due to the fact of the phoneme or initial sound is different. • The san languages of southwest Africa (which are spoken by the Ju/’hoansi and other ethnicities) use some sounds that are not found not only in the English language, but most other languages around the world. • The sounds they use are like clicks which serve as consonants, and the Ju/’hoansi language has distinct kinds of clicks that are produced pulling the tongue away from different locations in the mouth. The ju/’hoansi have an unusually large number of consonants, 48 click consonants to be precise, and they’re made up of 4 kinds of clicks which are dental, lateral, alveolar, and platal. • There are also five vowel qualities, however these may be nasalized, glottalized, murmured, or combinations of these, and most of these possibilities occur both long and short. There are about a good 30 vowel phonemes and in addition to many vowel sequences Ju’/hoansi grammatical rules for constructing sentences • Moving on from the phonology of language to morphology, morphology has to with a languages grammar and the grammatical rules for constructing sentences, and how the sounds of the phonemes are combined into larger units called morphemes • In a single morpheme, the plural diminutive enclitic (which basically means a word pronounced with so little emphasis that it is shortened and forms part of the preceding word, e.g., n't in can't.) only occur in loan words • Only a small set of consonants occur between vowels within roots, and they are Labial(sounds from lip), Alveolar(sounds articulated with the tongue against or close to the superior teeth), Velar(sounds pronounced with the back of the tongue near the soft palate), Uvular(sounds articulated with the back of the tongue), and Glottal (sounds articulated with the glottis and vocal cords) • Labials are very rare initially, though common between vowels. Also, velar stops (oral and nasal) are rare initially as well. Video of Ju/’hoansi man counting to ten in xuun dialect • ://https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JgMqd cCuLoU How the Ju/’hoansi use age and gender to classify people • Though children do not have a responsibility to provide food, they do periodically accompany their mothers in the gathering of food. While they are young, they are allowed to play and entertain themselves. When they grow older they are expected to provide a contribution to the village. In fact, a young man is only eligible to marry after making his first big game kill. In doing this he has proven he can support a wife and family. • On the contrary, a young woman is not considered a woman until she gains her first menstruation and finally has her first child, which is generally only after being married. • Usually by their early twenties men are able to start killing larger animals. These young men go through an initiation called Choma . This initiation lasts six weeks and allows for the ritual knowledge of male matters to be passed down from one generation to the next. These are the primary ways young men learn their place in society. • Elders, while few in number and unable to contribute to the group economically, are highly respected in the community. This is generally due to their knowledge of the culture. The elders give the Ju’/hoansi connection to their history and the ability to continue to preserve their culture as best as they could. How the Ju’/hoansi classify people based on descent relationships • Nuclear family members (shaded in green) are assigned unique terms, and extended family members are grouped into categories on a bilateral basis without any distinction between father's and mother's sides. Thus we could provide an exact English gloss for any of the terms above: tsu = uncle, ga = aunt, kuna/tun =cousin, tsuma = nephew/ni ece. • The gender of the speaker becomes a significant factor in the term given to nieces and nephews. Males use the term "tsuma" and females use the term "gama", a reflection of the fact that they are reciprocals of "tsu" and "ga". (the gama term is only used for sister's daughter but such a usage seems to involve an inconsistency). • The relative age of the speaker is also significant. The diagram above gives the terms for older siblings and cousins. Younger relatives receive a different designation as indicated in the following diagram. (Note that the younger cousin terms -- kuma and tuma -- are reciprocals of kuna and tun. Continued…. • The main feature that can now be observed is that the terms for older cousin (kuna/tun)are the same as the terms for grandparents, representing a principle that Lee identifies as an "equivalence of alternate generations". The same pattern is evident in the use of equivalent terms for: • uncle and great-grandfather (tsu) • aunt and great-grandmother(ga), and • niece/nephew and great grandchild (tsuma/gama). • The same patterning is reflected in the identification of younger cousins (kuma/tuma) with grandchildren as indicated below. Ju/’hoansi (San) Kinship chart and terms How the Ju’/hoansi raise children in some sort of family setting • The roles of men and women are taught to children through enculturation both directly and indirectly. Growing up, children, both boys and girls, accompany their mother when she gathers (some stay in the village and play). • When boys get a little older (around 12-14) they begin to go out on hunts with their fathers to observe. Usually by their early twenties young men are able to start killing larger animals. • Women, in turn, learn their roles through observation and direction given by their mothers. Young girls gather with their mothers and marry young (around 16). • The Ju/’hoansi rarely display aggression so their children have little opportunity to emulate aggressive behavior. • Whenever children do exhibit signs of aggression, adults quickly intervene to diffuse their hostilities. The close physical proximity of their huts— tightly clustered around central clearings—meant that children seldom got to play away from the ear of an adult, and aggression rarely had a chance to develop. How the Ju/’hoansi display a sexual division of labor • The !Kung(Ju/’hoansi) are an egalitarian society, meaning everyone has access to the valued resources. • The pattern of subsistence the Ju/’hoansi follow is foraging (hunting and gathering) • Everyone prized the meat that the men hunted but they really lived on the vegetable foods gathered by the women, which provided 60 to 80 percent of their diet. The women thus derived a lot of self-esteem from their contributions to their families. The women foraged many miles from the men without weapons, despite the possibility of encountering large predators such as lions and leopards. They did not need permission from men or assistance from them in their food-production work. Men and women could be absent from the camps for days at a time, so there was no inequality with men being gone while women maintained the home. The Ju/’hoansi valued the sexes nearly equally. • The roles of men and women are taught to children through enculturation both directly and indirectly. Growing up, children, both boys and girls, accompany their mother when she gathers (some stay in the village and play). • When boys get a little older (around 12-14) they begin to go out on hunts with their fathers to observe. Usually by their early twenties young men are able to start killing larger animals. • Women, in turn, learn their roles through observation and direction given by their mothers. Young girls gather with their mothers and marry young (around 16). How Ju/’hoansi display a concept of privacy • First and foremost Birth done in private. Ju/’hoansi women give unassisted birth walking away from the village camp as far as a mile during labor, and bearing the child alone, delivering it into a small leaf-lined hole dug into the warm sand. • When a young woman gets her first menstruation, she is brought to a hut made especially for the occasion, and no men are allowed in. During this time, it is considered very bad luck for the hunt if a man were to see the young woman's face. • The segregation of men and women during the celebration of a women's first menstruation is comparable to the secret segregation occurring for a young man's initiation. Other than these two instances, however, not much segregation among the sexes occurs. • The Ju/’hoansi are people of little privacy, due to their villages being arranged around central fires and families sleeping together in simple huts. When it comes to sex between the parents though, typically the parents try to be discreet about it. However, children often become aware of this and will lay awake at night to curiously observe it. • Lovers for married adults are also kept discreet, because it could cause a lot of conflicts with their spouse. There are many cases where a wife leaves her husband or a husband beats, even sometimes kills his wife, because of their lover Ju/’hoansi rules to regulate sexual behavior • Children of the Ju/’hoansi learn about sexual behavior at a very early age. • This is because of the limited amount of living space that has to be shared between families, resulting in parental sex being carried out discretely beneath the same blanket, while children are asleep. • When children reach around the age of 7 they start to catch on thanks to their curiosity, and go around and engage in sexual activities themselves. Adults know that the kids engage in sexual acts, because they did so themselves while they were younger, but if they see the kids doing it in front of them, they will scold them, as it is deemed disrespectful to perform such acts in front of your elders. • Up to the teenage age, children play in the village without having to cover their genitals. This attitude towards sex also means that sexual play is considered as a normal process of childhood, with children as up to the age of 15 mixing playtime and sexual activity. • An implication of this is that the meaning of ‘virginity’ as we know it is actually not valid in the !Kung context, since most children would have some experience with sexual activity very early, like around age 8 on average. • When looking at the adults, the adults can have sex with their spouses, or their lovers. However the lovers are kept discreet as to avoid any conflict and sexual relations are done when the husband is out, or outside in the bushes Distinguishing between good and bad Ju/’hoansi behavior • Good behavior - bringing meat into the village is highly celebrated, and a positive sanction(reward) men receive for this act is that they gain a larger range of influence and power in the village. • Bad behavior - Whenever children exhibit signs of aggression, they receive a negative sanction(punishment) of adults lecturing and scolding them. • Also they regard stinginess with great hostility, and are even more strongly opposed to arrogance. A hunter who announced his success to his camp, or a woman who made a point of displaying her gift to another is arrogant. They have negative sanctions which include downplaying gifts, selfdeprecating comments, rough humor, put-downs, and backhanded compliments for these actions Ju/’hoansi body ornamentation Continued • The Ju/’hoansi do not have much body ornamentation as children aren’t required to wear anything at all, and when they reach teenage years the men and women simply have to cover their genitals • Alot of the Ju/’hoansi adults and elders wear tattoo geometric designs on their foreheads and cheekbones • The women also wear beaded necklaces, and arm bands, and ostrich shell ornaments. • When the men go hunting they take pride in carrying their bows and arrows with them, and sometimes even decorate them Ju/’hoansi jokes and games • Since there are very few Ju/’hoansi children in each village, competitive games would be hard to organize since it would be difficult to find an age-mate to compete with, much less enough to form viable team sports. This accords with the Ju/’hoansi cultural opposition to competitiveness. While the children exhibit widely differing abilities in their games, they don't compete and all play for the sheer pleasure of it. • A lot of the games they play at a very young age are very sexual, such as pretend marriage, and this again has to do with their curiosity • With Ju/’hoansi jokes, a lot of jokes are made to have fun, but also to demean others because of inappropriate acts they commit, and are usually very sexual. • Eg. If a man makes an unwarranted sexual approach towards a woman, she’ll joke that he has a smelly penis. • There is actually a Joking kin, which means that there are only a certain designated people you’re allowed to make jokes to. You are expected to maintain affectionate relationships with them and mark you’re intimacy by extensive joking involving insults, mock threats, and ribald remarks (which is referring to sexual matters in an amusingly rude or irreverent way) • There is also an avoidance kin, which are people you are supposed to be respectful and reserved with, and in some extreme cases, such as mother-in-law/son-in-law relationships, you should not talk to each other at all. Ju/’hoansi art Continued • Trance Dances: At the all-night trance dances, the men dance around a circle of chanting, clapping women, who sometimes also join the dancing. As the dancing increases in energy, the n/um (energy) rises in the healers until they reach a state of !kia (altered consciousness) in which they can begin to cure physical and mental illnesses by laying their hands on the sick people and pulling out the sicknesses. • Namibian music: Music is an extension of practical language for the Ju/’hoansi bushmen. Examples of music they take part in is a collective of singing and healing songs (both as forms of entertainment) as well as singing games Continued • http://www.allmusic.com/album/namibiasongs-of-the-juhoansi-bushmen-mw0000063528 Ju/’hoansi leadership roles for the implementation of community decisions • The Ju/hoansi leadership practices are a very good example of egalitarianism. The Ju/hoansi do not have a headman or chief because that would cause a rift in the equality of the people. • Everyone is considered equal, men and women so a headman is unnecessary and could cause social problems. Instead of appointing a leader for the overall group, the Ju/hoansi practice ad-hoc leadership. • Ad hoc leadership is described as leadership for the certain task at hand and only for that time being. A leader may be appointed for a specific fishing trip but only for that trip. This keeps the people at a certain level so that no one thinks they are higher ranked of better than anyone else. • Discussions of issues that might lead to conflicts, such as laziness, stinginess, or unfair distribution of meat are normally maintained at the level of gossip, open criticism, or humor. Occasionally, when both parties become angry, conversations escalate to the level of a “talk,” which is characterized by sudden and spontaneous comments poured out at a rapid rate. If tempers flare, however, everyone tries to resolve the dispute before serious fighting erupts, but sometimes either a physical fight occurs or the group splits apart. Citations • http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ju%C7%80'hoan_dialect • https://umanitoba.ca/faculties/arts/anthropology/tuto r/case_studies/san/san_joke.html • https://umanitoba.ca/faculties/arts/anthropology/tuto r/case_studies/san/san_terms.html • http://social-shadow.tripod.com/family.html • http://www.peacefulsocieties.org/Society/Juhoan.html Thank you for viewing this presentation