View slides - AMSUS Continuing Education

TRAINING THE FORWARD DEPLOYED SURGEON:

IS ACS FELLOWSHIP THE ANSWER?

William Scott, DO

General Surgery Resident (PGY 4)

Nellis AFB, Las Vegas, NV

Disclosures

• The presenter has no financial relationships to disclose.

• This continuing education activity is managed and accredited by Professional

Education Services Group in cooperation with AMSUS.

• Neither PESG,AMSUS, nor any accrediting organization support or endorse any product or service mentioned in this activity.

• PESG and AMSUS staff has no financial interest to disclose.

• Commercial support was not received for this activity.

• The views and opinions herein are the author’s own private views and are not to be construed as official or reflecting the views of the US Air Force,

Department of Defense, or the United States Government.

Learning Objectives:

At the conclusion of this activity, the participant will be able to:

1. List the skill sets needed by a forward deployed surgeon.

2. Identify the role of the Acute Care Surgery (ACS) Fellowship curriculum in training the deployed surgeon.

3. Discuss the strengths of the fellowship curriculum is preparing the forward deployed surgeon.

4. Recognize the opportunity for comparable training of general surgeons unable to complete an ACS fellowship prior to deployment.

Personal Background

• 4 th year surgical resident at Nellis AFB, Las Vegas, NV.

• After an internship, spent 4 years as a General Medical Officer at Nellis AFB in the Family Medicine clinic

• 2 tours

• Afghanistan 2009

• Liberia 2011

• Returned to residency in 2012

Background

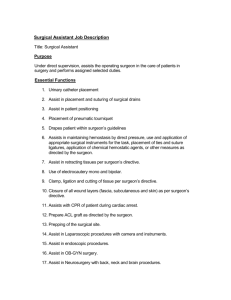

• Varied skills are required at the first echelon of surgical care

• These operations are the first stage of complex surgical care

• Staffing at forward surgical units is not uniform

• The general surgeon must perform a range of surgical specialty operations

• The typical military general surgeon does not possess the diverse skill set needed

• Would training in an acute care surgery (ACS) fellowship fill this knowledge gap?

Methods

• Joint Trauma Theater Registry was queried for procedures performed at forward surgical units from 2002-2012

• These procedures were then organized by type

• Procedures were compared to the revised 2014 ACS fellowship case requirements

ROLE I - TIC

Battalion

Aid Station

ROLE II - FOB

Forward

Surgical

Team

ROLE III – BAF/KAF

Combat

Support

Hospital

ROLE IV - LRMC

Definitive

Care

REVISED 2014 ACS FELLOWSHIP CASE REQUIREMENTS:

Head and Neck

Organ Management

ICP – 5

Nasal Packing – 2

Trachostomy – 10

Crichothyroidotomy – 2

Thoracic

Thoractomy – 10 pleura – 5

Throacoscopy – 10

Sternotomy – 10

Pericardiotomy – 5

Organ Management

Lung – 35

Operative evacuation of the

Parenchymal procedures – 10

Broncoscopy – 20

Diaphgram – 5

Cardiac – 5

Esphagus – 2

Intrathoracic great vessel injury – 3

Case Requirements

Abdominal

Endoscopy – 20

Enteral Access – 10

Laparotomy – 10

Diagnostic laparoscopy – 5

Hepatic Mobilization – 2

Damage control technique – 10

Complex laparoscopy – 10

Organ Management

Liver – 5

Spleen – 2

Kidney – 3

Pancreas – 5

Stomach – 5

Duodenum – 2

Small Intestine – 10

Colon/Rectum – 10

Appendix – 15

Anus – 5

Biliary System – 3

Bladder – 3

Ureter – 1

Case Requirements

Vascular

LMVR – 2

RMVR – 5

Infrarenal aorto-pelvic exposure – 3

Brachial exposure – 3

Femoral – 5

Popliteal – 2

Retrograde balloon occlusion of the aorta –

Ultrasound

FAST – 25

Thoracic ultrasound for function – 15

Thoracic ultrasound for drainage – 5

Ultrasound guided central line insertion – 5

5

Organ Management

Arterial injury – 10

Amputation – 3

Fasciotomy – 5

Results

• Over a 10 year period (2002-2012)

• 34,411 procedures performed on 9,363 patients

• Mean age 25.9 years

• 80.6% injuries were battle related

Results

• Dominant injuries demographics:

• Explosive: 59.2% were penetrating and 38.1% were blunt

• 48.3% were injured during OIF

• 51.6% were injured during OEF

• Mean ISS of these patients was 12.4 (IQR 5-17).

ISS Example

Trauma.org

Results

• The 34,411 procedures were grouped into categories

• 27,439 operative procedures

• 6,972 non-operative but critical procedures

• 2,279 FAST exams

• 1,735 splint/casting

• 1,040 tube thoracostomies

• 1,918 ICU patients managed

• 2,157of the operative cases were primarily orthopedic

• 758 amputations

• 501 definitive internal fixation

Operative Cases

Soft Tissue (26%)

Vascular (19%)

Ex Fix (13%)

Alimentry Tract (12%)

Laparotomy (including

Diaphram) (11%)

Fasciotomy (9%)

Other (8%)

Thoracic (4%)

Critical Non-operative Procedures

FAST (33%)

Splint/Cast (25%)

Tube Thoracostomy

(15%)

ICU Management

(28%)

Results

• 99.7% of these procedures are part of the ACS fellowship curriculum

• 27 operative cases were not included in the fellowship curriculum

• 3 gynecologic operations and 24 burns/grafting

Take Home Thought #1

• The ACS curriculum replicates the operative and non-operative skill sets needed by forward deployed surgeons

Why don’t we do this with everyone?

• Cost of training

• Budgeting costs for additional trainees

• Lost man hours during training

• Lag time until trainees enter deployment pool

• Accrual of commitment by trainees

• Duty station limitations after training to maintain skill set

• Limited locations

• Current combat injury survival implies forward surgical care is adequate

• Survivability scores

Cost of Training

• Budgeting for more ACS fellowship trained physicians

• Rank pay over 2 year period

• Change in Bonus pay from general surgeon to trauma surgeon

• Lost work during training

• 2 years missing a general surgeon at current duty station

• 2 years that you

Cost of Training

• Lag time until trainees enter deployment pool

• 2 years missing a general surgeon who can deploy

• Accruing further commitment time

• 2 years of commitment for fellowship (4 years total of opportunity cost)

• 2 years of payback will likely increase deployment exposure

Limited Duty Stations

• Duty stations that allow maintenance of this skill set are limited

• Larger Military Treatment Facilities (MTFs)

• Civilian training agreements

• Decreases the available general surgeons who are needed to staff non-acute care locations

Current Efficiency

• Combat injured who reached role III had a > 90% survivability over this period

• Nessen et al showed that FSTs could provide comparable care to other locations in the deployed setting

• No data on what level of training and/or experience of the individual surgeon’s had at role II facilities and whether complications/mortality differed

Take Home Thought #2

• While the ACS curriculum is clearly the best training model and correlates with the training regime best suited for the forward deployed surgeon, the opportunity cost limits the number of available spots that can be set aside each year

What’s the alternative?

• If we can’t send everyone to ACS fellowship, what can we do to prepare them for the front line surgical experience?

The current training model

• General Surgery residency

• Orthopedic residency

• Pre-deployment Training

• Center for the Sustainment of Trauma and Readiness Skills (C-STARS)

• Sustained Medical And Readiness Training (SMART)

• Emergency War Surgery (EWS)

• Advanced Surgical Skills for Exposure in Trauma (ASSET)

CSTARS

• St. Louis, Baltimore, Cincinnati

• 21-day course that offers:

Trauma lectures

Human Simulator Sessions

Human Cadaver Lab

Baltimore City Ambulance Rotation

Trauma Resuscitations in the STC Trauma Resuscitation Unit (TRU), ICU, ER and John’s Hopkins Regional burn ICU

Equipment Skills Stations

Maryland State Trooper Helicopter rotation (as available)

Trauma/Critical Care case studies

Clinical duties as determined by specialty

SMART

• Las Vegas

• 14 day experience with focus on direct patient care

• Tailored to rotator’s identified needs / weaknesses

• Includes traumatically injured as well as emergency general surgery cases

• Includes an emphasis on ICU concepts and care

• Additional informal discussions of current literature and practices with embedded faculty

• Has flexibility to include other surgical specialties as desired

EWS

• San Antonio

• Developed in 1991

• 3 day refresher/review course

• 20 hours of trauma lecture

• 6.5 hours of human cadaver lab

• Reviews war wounds, shock and resuscitation, damage control, injury patterns, etc.

ASSET

• Multiple locations nationwide

• 1 day course

• Reviews anatomy for trauma surgery exposure

• Cadaver lab with practice dissections

Waving Goodbye

• Courses often waived because of small spin up time prior to deployment

• Many surgeons “get out” of this training and “slip through the cracks”

Take Home Thought #3

• General Surgery Residency alone is not sufficient training

• Ideal training simulates the ACS fellowship experience

• Current options that mirror this curriculum are limited to

C-STARS, EWS and the SMART programs

Thank you for your time

Questions?

Obtaining CME/CE Credit

If you would like to receive continuing education credit for this activity, please visit: http://amsus.cds.pesgce.com