John Adams (miniseries) film notes

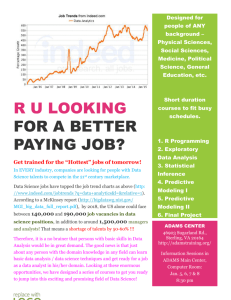

advertisement

John Adams (miniseries) film notes John Adams Television promotional poster Genre Biographical miniseries Directed by Tom Hooper Tom Hanks (executive) Produced by David Coatsworth Kirk Ellis Gary Goetzman (executive) Written by Based on Kirk Ellis John Adams by David McCullough Paul Giamatti Laura Linney Stephen Dillane David Morse Starring Tom Wilkinson Danny Huston Rufus Sewell Justin Theroux Guy Henry Music by Robert Lane Joseph Vitarelli Budget $100,000,000[1] Country United States Language English Original run March 16, 2008 – April 27, 2008 Running time 8 hours, 20 minutes No. of episodes 7 John Adams is a 2008 American television miniseries chronicling most of U.S. President John Adams' political life and his role in the founding of the United States. Paul Giamatti portrays John Adams. The miniseries was directed by Tom Hooper. Kirk Ellis wrote the screenplay based on the book John Adams by David McCullough. The biopic of John Adams and the story of the first fifty years of the United States was broadcast in seven parts by HBO between March 16 and April 20, 2008. John Adams received widespread critical acclaim, and many prestigious awards. The show won four Golden Globe awards and thirteen Emmy awards, more than any other miniseries in history. Plot summary Part I: Join or Die (1770 A.D. - 1774 A.D.) The first episode opens with a cold winter in Boston on the night of the Boston Massacre. It portrays John Adams arriving at the scene following the gunshots from British soldiers firing upon a mob of Boston citizens. Adams, a respected lawyer in his mid30s known for his belief in law and justice, is therefore summoned by the accused Redcoats. Their commander, Captain Thomas Preston asks him to defend them in court. Reluctant at first, he agrees despite knowing this will antagonize his neighbors and friends. Adams is depicted to have taken the case because he believed everyone deserves a fair trial and he wanted to uphold the standard of justice. Adams' cousin Samuel Adams is one of the main colonists opposed to the actions of the British government. He is one of the executive members of the Sons of Liberty, an anti-British group of agitators. Adams is depicted as a studious man doing his best to defend his clients. The show also illustrates Adams' appreciation and respect for his wife, Abigail. In one scene, Adams is shown having his wife proofread his summation as he takes her suggestions. After many sessions of court, the jury returns verdicts of not guilty of murder for each defendant. The episode also illustrates the growing tensions over the Coercive Acts ("Intolerable Acts"), and Adams' election to the First Continental Congress. Part II: Independence (1774 A.D. - 1776 A.D.) The second episode covers the disputes among the members of the Second Continental Congress towards declaring independence from Great Britain as well as the final drafting of the Declaration of Independence. At the continental congresses Adams is depicted as the lead advocate for independence. He is in the vanguard in establishing that there is no other option than to break off and declare independence. He is also instrumental in the selection of then-Colonel George Washington as the new head of the Continental Army. However, in his zeal for immediate action, he manages to alienate many of the other founding fathers, going so far as to insult a peace-loving Quaker member of the Continental Congress, implying that the man suffers from a religiously based moral cowardice, making him a "snake on his belly". Later, Benjamin Franklin quietly chastens Adams, saying, "It is perfectly acceptable to insult a man in private and he may even thank you for it afterwards but when you do so publicly, it tends to make them think you are serious." This points out Adams' primary flaw: his bluntness and lack of gentility toward his political opponents, one that would make him many enemies and which would eventually plague his political career. It would also, eventually, contribute to historians' disregard for his many achievements. The episode also shows how Abigail innovatively copes with issues at home as her husband was away much of the time participating in the Continental Congress. She employs the use of then pioneer efforts in the field of preventative medicine and vaccination against smallpox for herself and the children. Part III: Don't Tread on Me (1777 A.D. - 1781 A.D.) In Episode 3, Adams travels to Europe with his young son John Quincy during the war seeking alliances with foreign nations, during which the ship transporting them battles a British frigate. It first shows Adams' embassy with Benjamin Franklin in the court of Louis XVI of France. The old French nobility, who are in the last decade before being consumed by the French Revolution, are portrayed as effete and decadent. They meet cheerfully with Franklin, seeing him as a romantic figure, little noting the democratic infection he brings with him. Adams, on the other hand, is a plain spoken and faithful man, who finds himself out of his depth surrounded by an entertainment- and sex-driven culture among the French elite. Adams finds himself at sharp odds with Benjamin Franklin, who has adapted himself to the French, seeking to obtain by seduction what Adams would gain through histrionics. Franklin sharply rebukes Adams for his lack of diplomatic acumen, describing it as a "direct insult followed by a petulant whine". Franklin soon has Adams removed from any position of diplomatic authority in Paris. His approach is ultimately successful and was to result in the conclusive Franco-American victory at Yorktown. Adams, chastened and dismayed but learning from his mistakes, then travels to the Dutch Republic to obtain monetary support for the Revolution. Although the Dutch agree with the American cause, they do not consider the new union a reliable and trustworthy client. Adams ends his time in the Netherlands in a state of progressive illness, having sent his son away as a diplomatic secretary to the Russian Empire. Part IV: Reunion (1781 A.D. - 1789 A.D.) The fourth episode shows John Adams being notified of the end of the Revolutionary War and the defeat of the British. He is then sent to Paris to negotiate the Treaty of Paris in 1783. While overseas, he spends time with Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson and Abigail visits him. Franklin informs John Adams that he was appointed as the first United States Ambassador to the United Kingdom and thus has to relocate to the British Court of St. James's. John Adams is poorly received by the British during this time—he is the representative for a recently hostile power, and represents in his person what many British at the time regarded as a disastrous end to its early Empire. He meets with his former sovereign, King George III, and while the meeting is not a disaster, he is excoriated in British newspapers. In 1789, he returns to Massachusetts for the first Presidential Election and he and Abigail are reunited with their children, now grown. George Washington is elected the first President of the United States and John Adams as the first Vice President. Initially, Adams is disappointed and wishes to reject the post of Vice President because he feels there is a disproportionate number of electoral votes in favor of George Washington (Adams number of votes pales in comparison to those garnered by Washington). In addition, John feels the position of Vice President is not a proper reflection of all the years of service he has dedicated to his nation. However, Abigail successfully influences him to accept the nomination. Part V: Unite or Die (1788 A.D. - 1797 A.D.) The fifth episode begins with John Adams presiding over the Senate and the debate over what to call the new President. It depicts Adams as frustrated in this role: His opinions are ignored and he has no actual power, except in the case of a tied vote. He's excluded from George Washington's inner circle of cabinet members, and his relationships with Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton are strained. Even Washington himself gently rebukes him for his efforts to "royalize" the office of the Presidency. A key event shown is the struggle to enact the Jay Treaty with Britain, which Adams himself must ratify before a deadlocked Senate (although historically his vote was not required). The episode concludes with his inauguration as the second president—and his subsequent arrival in a plundered executive mansion. Part VI: Unnecessary War (1798 A.D. - 1802 A.D.) The sixth episode covers Adams's term as president and the rift between the Hamilton-led Federalists and Jefferson-led Republicans. Adams's neutrality pleases neither side and often angers both. His shaky relationship with his vice president, Thomas Jefferson, is intensified after taking defensive actions against the French because of failed diplomatic attempts and the signing of the Alien and Sedition Acts. However, Adams also alienates himself from the anti-French Alexander Hamilton after taking all actions possible to prevent a war with France. Adams disowns his son Charles, who soon dies as an alcoholic vagrant. Late in his Presidency, Adams sees success with his campaign of preventing a war with France, but his success is clouded after losing the presidential election of 1800. After receiving so much bad publicity while in office, Adams lost the election against his Vice-President, Thomas Jefferson, and runner-up Aaron Burr (both from the same party). This election is now known as the Revolution of 1800. Adams leaves the Presidential Palace (now known as The White House), retiring to his personal life in Massachusetts, in March 1801. Part VII: Peacefield (1803 A.D. - 1826 A.D.) The final episode covers Adams's retirement years. His home life is full of pain and sorrow as his daughter, Nabby, dies of breast cancer and Abigail succumbs to typhoid fever. Adams does live to see the election of his son, John Quincy, as president, but is too ill to attend the inauguration. Adams and Jefferson are reconciled through correspondence in their last years, and both die mere hours apart on the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence (July 4th); Jefferson was 83, Adams was 90. Cast Paul Giamatti as John Adams Laura Linney as Abigail Adams Stephen Dillane as Thomas Jefferson David Morse as George Washington Tom Wilkinson as Benjamin Franklin Rufus Sewell as Alexander Hamilton Justin Theroux as John Hancock Danny Huston as Samuel Adams Clancy O'Connor as Edward Rutledge Željko Ivanek as John Dickinson Ebon Moss-Bachrach as John Quincy Adams Sarah Polley as Abigail Adams Smith Andrew Scott as William S. Smith John Dossett as Benjamin Rush Mamie Gummer as Sally Smith Adams Caroline Corrie as Louisa Adams Samuel Barnett as Thomas Adams Kevin Trainor as Charles Adams Tom Hollander as King George III Damien Jouillerot as King Louis XVI Guy Henry as Jonathan Sewall Brennan Brown as Robert Treat Paine Paul Fitzgerald as Richard Henry Lee Tom Beckett as Elbridge Gerry Del Pentecost as Henry Knox Tim Parati as Caesar Rodney John O'Creagh as Stephen Hopkins John Keating as Timothy Pickering Hugh O'Gorman as Thomas Pinckney Timmy Sherrill as Charles Lee Judith Magre as Madame Helvetius Jean-Hugues Anglade as comte de Vergennes Jean Brassard as Admiral d'Estaing Pip Carter as Francis Dana Sean McKenzie as Edward Bancroft Derek Milman as Lieutenant James Barron Patrice Valota as Jean-Antoine Houdon Nicolas Vaude as Chevalier de la Luzerne Bertie Carvel as Lord Carmarthen Alex Draper as Robert Livingston Julian Firth as Duke of Dorset Cyril Descours as Edmund Charles Genet Alan Cox as William Maclay Sean Mahan as Gen. Joseph Warren Eric Zuckerman as Thomas McKean Ed Jewett as James Duane Vincent Renart as Andrew Holmes Ritchie Coster as Captain Thomas Preston Lizan Mitchell as Sally Hemmings Pamela Stewart as Patsy Jefferson Buzz Bovshow as John Trumbull Shooting locations The 110-day shoot took place in Colonial Williamsburg, Virginia; Richmond, Virginia and Budapest, Hungary.[2][3] Some European scenes were shot in Keszthely, Sóskút, Fertőd and Kecskemét, Hungary.[4] One location used in Colonial Williamsburg was the interior of Bruton Parish Church which was the site for the town meeting during which Adams gives a speech from the elevated pulpit. The brick wall surrounding Bruton Parish church was the backdrop for a separate outdoor scene. Another scene shot at Colonial Williamsburg was the one in which Adams first meets the British soldiers accused of murder for their roles in the Boston Massacre which was shot at the "public gaol", or jail where lawbreakers were held awaiting trial. Greenhow store exterior was used in place of a Trenton, NJ tavern that Adams frequented. The Wythe House stood in for the president's house in Philadelphia, though it was modified by a brick facade to mask the wooden fence. The Palace Green was used for the scene showing a tent and 40 coffins to represent Philadelphia's 1793 yellow fever epidemic. Sand scattered on the streets masked the modern pavement. The Palace Green also was the backdrop for a public riot staged in front of the George Wythe house, which represented the president's residence in Philadelphia. Scores of extras were used in this scene. British officers ransacked an abandoned Continental Army war room in a separate scene set in the Robert Carter house. Williamsburg's Public Hospital was in the background of the tent encampment of the Continental army which Adams visited in the winter of 1776, which was replicated using specialeffects snow. The College of William and Mary's Wren Building represented a Harvard interior. Scenes were also filmed at the Governor's Palace.[5][6] Richmond, Virginia was the site of the set, stage space, backlot and production offices, in an old Mechanicsville AMF warehouse. Sets which included cobblestone streets and colonial storefronts were created for filming outdoor street scenes in colonial cities of Washington D.C., Boston, and Philadelphia. Countryside surrounding Richmond in Hanover County and Powhatan County were chosen to represent areas surrounding early Boston, New York, and Philadelphia.[7][8] Soundtrack The score for the miniseries was composed by Rob Lane and Joseph Vitarelli. The two composers worked independently of each other, with Lane writing and recording his segments in London and Vitarelli in Los Angeles.[9] The soundtrack was released on the Varèse Sarabande label. The main theme heard during opening credits is also played before Washington Nationals home games during the presentation of the national colors. A shortened version was also used as introductory music for coverage of the 2010 congressional elections and 2012 Presidential elections on CNN.[citation needed] Critical reception The critical reception to the miniseries was predominantly positive. Metacritic rates the critical response at 78 out of 100 based upon 27 national reviews.[10] Ken Tucker of Entertainment Weekly rated the miniseries A-,[11] and Matt Roush of TV Guide praised the lead performances of Paul Giamatti and Laura Linney.[12] David Hinckley of the New York Daily News felt John Adams "is, quite simply, as good as TV gets . . . Best of all are two extraordinary performances at the center: Paul Giamatti as Adams and Laura Linney as his wife, Abigail . . . To the extent that John Adams is a period piece, it isn't quite as lush as, say, some BBC productions. But it looks fine, and it feels right, and sometimes what's good for you can also be just plain good."[13] Alessandra Stanley of the New York Times had mixed feelings. She said the miniseries has "a Masterpiece Theatre gravity and takes a more somber, detailed and sepia-tinted look at the dawn of American democracy. It gives viewers a vivid sense of the isolation and physical hardships of the period, as well as the mores, but it does not offer significantly different or deeper insights into the personalities of the men — and at least one woman — who worked so hard for liberty . . . [It] is certainly worthy and beautifully made, and it has many masterly touches at the edges, especially Laura Linney as Abigail. But Paul Giamatti is the wrong choice for the hero . . . And that leaves the mini-series with a gaping hole at its center. What should be an exhilarating, absorbing ride across history alongside one of the least understood and most intriguing leaders of the American Revolution is instead a struggle."[14] Among those unimpressed with the miniseries were Mary McNamara of the Los Angeles Times[15] and Tim Goodman of the San Francisco Chronicle.[16] Both cited the miniseries for poor casting and favoring style over storytelling. Historical inaccuracies According to Jeremy Stern, writing on History News Network, the series deviates greatly from David McCullough's book, creating serious historical errors throughout.[17] Part I John Hancock, after being confronted by a British customs official, orders the crowd to "Teach him a lesson, tar the bastard". Hancock and Samuel Adams then look on while the official is tarred and feathered, to the disapproval of John Adams. The scene is fictional and does not appear in McCullough's book. According to Samuel Adams biographer Ira Stoll, there's no evidence that Samuel Adams and John Hancock, who were opposed to mob violence, were ever present at a tarring and feathering, and so the scene succeeds in "tarring the reputations of Hancock and Samuel Adams".[18] Jeremy Stern writes that, "Despite popular mythology, tarrings were never common in Revolutionary Boston, and were not promoted by the opposition leadership. The entire sequence is pure and pernicious fiction."[17] According to Stern, the scene is used to highlight a schism between Samuel and John Adams, which is entirely fictional.[17] Captain Preston and the British soldiers involved in the Boston Massacre are tried in a single trial in the seeming dead of winter and declared not guilty of all charges. In actuality, Captain Preston's trial took place on October 24 and ran through October 29, when he was found not guilty. The eight soldiers were brought to trial weeks later in a separate trial that concluded on November 29. Six of the soldiers were found not guilty but two, Hugh Montgomery and Hugh Killroy were convicted of manslaughter. They both received brands on their right thumbs as punishment.[19] In the tar and feather scene, a black, modern tar was used. In reality, the liquid known as tar in the 18th century was actually pine tar (a much clearer liquid). The tar we know today is actually called petroleum tar or bitumen. Pine tar also has a low melting point, and in the scene John Adams was portraying this act as a "brutal" act of violence. In reality, a tar and feathering was an act of humiliation, not brutality. Part II In the opening scene, the final meeting site of the First Continental Congress is incorrectly shown as the Pennsylvania State House (now known as Independence Hall). In fact, the First Continental Congress was held in Carpenters' Hall, located approximately 250 yards (230 m) east of the state house, along Chestnut Street. Carpenters' Hall, which was and still is privately owned by The Carpenters' Company of the City and County of Philadelphia, offered more privacy than the Pennsylvania State House. The venue depicted for the Second Continental Congress is, however, correctly depicted as the Pennsylvania State House.[20] Benjamin Franklin is shown being brought to the Continental Congress in a palanquin, but he did not use this mode of transport in Philadelphia until the Constitutional Convention, 11 years later. John Adams did not ride to Lexington and Concord while the battle was still in progress; he visited on April 22, several days later.[21] The first version of the Declaration of Independence read by Adams’ family was depicted as a printed copy; in reality, it was a copy in Adams’ own hand, which led Mrs. Adams to believe that he had written it himself.[22] General Henry Knox's ox-driven caravan of cannon (taken from Fort Ticonderoga) is depicted passing by the Adams' house in Braintree, Massachusetts en route to Cambridge, Massachusetts. In reality, General Knox's caravan almost certainly did not pass through Braintree. Ft. Ticonderoga, being in upstate New York, is northwest of Cambridge, and Knox is assumed to have taken the most likely routes of the day: from the New York border through western and central Massachusetts via what are now Routes 23, 9, and 20; thus never entering Braintree, which is located approximately 15 miles (24 km) southeast of Cambridge.[23] When the doctor questions Abigail Adams if she has asked her husband regarding the family's smallpox inoculation (variolation) of 1775, she knows he would approve without asking him because he himself was inoculated in 1764, so the doctor's question and her response were misleading. The illness of the daughter following the inoculation was inaccurate. In fact it was their son, Charles, who developed the pox and who was unconscious and delirious for 48 hours. The series also shows the children suffering from the effects of the inoculation while Abigail and the daughter read the newly drafted Declaration, which would have been sometime in July of 1776.[24][25] Part III Adams is shown departing for Europe without an upset nine-year-old son Charles, leaving only with older son John Quincy Adams. According to David McCullough's book, young Charles accompanied his brother and father to Paris. He later became ill in Holland, and traveled alone on the troubled vessel South Carolina. After an extended journey of five months, Charles returned to Braintree at 11 years of age. During Adams's first voyage to France, his ship engages a British ship in a fierce battle while Adams assists a surgeon performing an amputation on a patient who dies. In reality, Adams helped perform the amputation several days after the capture of the British ship, following an unrelated accident. The patient died a week after the amputation, rather than during the operation as shown in the episode.[26] Part IV Abigail Adams is depicted reprimanding Benjamin Franklin for cheating on his wife in France, but his wife died seven years earlier in 1774. Multiple references are made in dialogue throughout the episode to the impending "Constitutional Convention." In reality, the Constitutional Convention was only referred to as such after it disbanded, since the Philadelphia convention was originally called only to revise the Articles of Confederation. When the Convention met, strict secrecy was imposed on its proceedings. It was only under this veil of secrecy that the convention goers changed their mission from one of revising the Articles to one of crafting a new constitution. Part V Then-Vice President John Adams is shown casting the tiebreaker vote in favor of ratifying the Jay Treaty. In reality, his vote was never required as the Senate passed the resolution by 20-10.[27] Furthermore, the vice president would never be required to cast a vote in a treaty ratification because Article II of the Constitution requires that treaties receive a two-thirds vote. Nabby Adams meets and marries Colonel William Stephens Smith upon her parents' return to America from London. John Adams is depicted as refusing to use his influence to obtain political positions for his daughter's new husband, though Colonel Smith requests his father-in-law's assistance repeatedly with an almost grasping demeanor. Mr. Adams upbraids his son-in-law each time for even making the request, stating that Colonel Smith should find himself an honest trade or career and not depend upon speculation. In reality, Nabby met Colonel Smith abroad while her father was serving as United States Ambassador to France and Great Britain, and the couple married in London prior to the end of John Adams' diplomatic posting to the Court of St. James. Both John and Abigail used their influence to assist Colonel Smith and obtain political appointments for him, although this did not curb Colonel Smith's tendency to invest unwisely.[citation needed] Following his election as President, John Adams is shown delivering his inauguration speech in the Senate chamber, on the 2nd floor of Congress Hall, to an audience of Senators. The speech was actually given in the much larger House of Representatives chamber on the first floor of Congress Hall.[28] The room was filled to capacity with members of both the House and Senate, justices of the Supreme Court, heads of departments, the diplomatic corps, and others.[29] Part VII After then-President Adams refuses to assist Colonel Smith for the last time, Smith is depicted as leaving Nabby and their children in the care of the Adams family at Peacefield; according to the scene, his intention is to seek opportunities to the west and either return or send for his family once he can provide for them. Nabby is living with her family when she discerns the lump in her right breast, has her mastectomy, and dies two years later. Smith does not return until after Nabby's death and it is implied that he has finally established a stable form of income; whether he was returning for his family as he had promised or was summoned ahead of his own schedule by the Adams' pursuant to Nabby's death is not specified. In reality, Smith brought his family with him from one venture to the next, and Nabby only returned to her father's home in Massachusetts after it was determined that she would undergo a mastectomy rather than continue with the potions and poultices prescribed by other doctors at that time. Smith was with her during and after the mastectomy, and by all accounts had thrown himself into extensive research in attempts to find any reputable alternative to treating his wife's cancer via mastectomy. The mastectomy was not depicted in the series as it is described in historical documents. In fact, Nabby's tumor was in the left breast. She returned to the Smith family home after her operation and died in her father's home at Peacefield only because she expressed a wish to die there, knowing that her cancer had returned and would kill her, and her husband acceded to her request. Dr. Benjamin Rush was also not the surgeon who conducted the operation.[30] Adams is shown inspecting John Trumbull's painting Declaration of Independence (1817) and stating that he and Thomas Jefferson are the last surviving people depicted. This is inaccurate since Charles Carroll of Carrollton, who is also depicted in the painting, survived until 1832. In fact, Adams never made such a remark. In reality, when he inspected Trumbull's painting, Adams' only comment was to point to a door in the background of the painting and state, "When I nominated George Washington of Virginia for Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army, he took his hat and rushed out that door."[31] Benjamin Rush is portrayed as encouraging Adams to start a correspondence with Thomas Jefferson after the death of Abigail Adams. Abigail's death occurred in 1818 but the Adams-Jefferson correspondence started in 1812, and Rush died in 1813.[17] Awards and nominations Primetime Emmy Awards John Adams received twenty-three Emmy Award nominations, and won thirteen, beating the previous record for wins by a miniseries set by Angels in America. It also holds the record for most Emmy wins by a program in a single year.[citation needed] Year 2008 Category Outstanding Miniseries Nominee(s) Tom Hanks, Gary Goetzman, Kirk Ellis, Episode Result Won Frank Doelger, David Coatsworth and Steve Shareshian Outstanding Writing for a Miniseries or Movie Outstanding Lead Actor in a Miniseries or Movie Outstanding Lead Actress in a Miniseries or Movie Outstanding Supporting Actor in a Miniseries or Movie Kirk Ellis Episode 2, Independence Won Paul Giamatti Won Laura Linney Won Tom Wilkinson Won Gemma Jackson, David Outstanding Art Crank, Direction for a Christina Miniseries or Moore, Kathy Movie Lucas and Sarah Whittle Outstanding Kathleen Won Won Casting for a Chopin, Nina Miniseries, Gold and Tracy Movie or a Kilpatrick Special Outstanding Cinematography Episode 2, Tak Fujimoto For A Miniseries Independence or Movie Outstanding Donna Costumes for a Zakowska, Episode 4, Miniseries, Amy Andrews Reunion Movie or a and Clare Special Spragge Outstanding Trefor Proud, Prosthetic John R. Makeup for a Bayless, Chris Series, Burgoyne and Miniseries, Matthew W. Movie or a Mungle Special Stephen Hunter Flick, Vanessa Lapato, Curt Outstanding Schulkey, Sound Editing Episode 3, Randy Kelley, for a Miniseries, Don't Tread Kenneth L. Movie or a On Me Johnson, Paul Special Berolzheimer, Dean Beville, Bryan Bowen, Won Won Won Won Patricio A. Libenson, Solange S. Schwalbe, David Lee Fein, Hilda Hodges and Alex Gibson Outstanding Jay Meagher, Sound Mixing Marc Fishman for a Miniseries and Tony or a Movie Lamberti Erik Henry, Jeff Goldman, Paul Graff, Outstanding Steve Special Visual Kullback, Effects for a Christina Miniseries, Graff, David Movie, or Van Dyke, Dramatic Robert Special Stromberg, Ed Mendez and Ken Gorrell Outstanding Directing for a Miniseries, Tom Hooper Movie or Dramatic Special Episode 3, Don't Tread On Me Won Episode 1, Join or Die Won Nominated Outstanding Supporting Actor in a Miniseries or Movie Outstanding Supporting Actor in a Miniseries or Movie Outstanding Cinematography for a Miniseries or Movie Outstanding Hairstyling for a Miniseries or a Movie Outstanding Makeup for a Miniseries or a Movie (Nonprosthetic) Outstanding Original Dramatic Score for a Miniseries, Movie or a Special Outstanding Stephen Dillane Nominated David Morse Nominated Tak Fujimoto and Danny Cohen Episode 3, Don't Tread Nominated On Me Jan Archibald and Loulia Sheppard Nominated Trefor Proud and John R. Bayless Nominated Robert Lane Episode 2, Nominated Independence Melanie Oliver Episode 2, Nominated Single-camera Picture Editing for a Miniseries or a Movie Jon Johnson, Bryan Bowen, Kira Roessler, Vanessa Lapato, Eileen Horta, Virginia CookMcGowan, Outstanding Samuel C. Sound Editing Crutcher, Mark for a Miniseries, Messick, Movie or a Martin Special Maryska, Greg Stacy, Patricio A. Libenson, Solange S. Schwalbe, Hilda Hodges and Nicholas Viterelli Outstanding Jay Meagher, Sound Mixing Michael for a Miniseries Minkler and or a Movie Bob Beemer Golden Globe Awards Independence Episode 6, Unnecessary Nominated War Episode 5, Nominated Unite Or Die It was nominated for four awards at the 66th Golden Globe Awards and won all four.[32] Year Category Best Mini-Series Or Motion Picture Made for Television Best Performance by an Actress In A Mini-series or Motion Picture Made for Television 2009 Best Performance by an Actor in a Mini-Series or Motion Picture Made for Television Best Performance by an Actor in a Supporting Role in a Series, MiniSeries or Motion Picture Made for Television Nominee(s) Result Won Laura Linney Won Paul Giamatti Won Tom Wilkinson Won Screen Actors Guild Awards It was also nominated for three awards at the 15th Screen Actors Guild Awards and won two. Year Category Nominee(s) Result Outstanding Performance by a Laura Female Actor in a Television Won Linney Movie or Miniseries Outstanding Performance by a 2009 Paul Male Actor in a Television Movie Won Giamatti or Miniseries Outstanding Performance by a Tom Nominated Male Actor in a Television Movie Wilkinson or Miniseries Other awards The show also won a 2008 AFI Award for best television series.[33] References 1. Jump up ^ Catlin, Roger (March 11, 2008). "HBO miniseries gives John Adams his due". The Courant. Hartford, Connecticut: Hartford Courant. Retrieved May 10, 2014. 2. Jump up ^ Gary Strauss (2008-03-12). "For Giamatti, John Adams was 'endlessly daunting' role". USA Today (Gannett Company, Inc.). Retrieved 2009-01-11. 3. Jump up ^ Martin Miller (2008-03-16). "A revolutionary leading man". Los Angeles Times (Tribune Company). Retrieved 2009-01-11. 4. Jump up ^ "Tom Hanks a magyar stábnak is köszönetet mondott a Golden Globe-gálán". MTI (Hungarian news agency) (in Hungarian). 2009-01-12. Retrieved 2008-0112.[dead link] 5. Jump up ^ "aboutrufus.com". aboutrufus.com. Retrieved 2013-07-01. 6. Jump up ^ [1][dead link] 7. Jump up ^ http://www2.richmond.com/content/2007/jun/05/apresidential-production/ 8. Jump up ^ [2][dead link] 9. Jump up ^ John Adams at ScoringSessions.com 10. Jump up ^ "John Adams - Season 1 Reviews". Metacritic. 2008-03-16. Retrieved 2013-07-01. 11. Jump up ^ "John Adams Review | TV Reviews and News". EW.com. 2008-03-12. Retrieved 2013-07-01. 12. Jump up ^ [3][dead link] 13. Jump up ^ "'John Adams' is a triumph". New York: NY Daily News. 2008-03-13. Retrieved 2013-07-01. 14. Jump up ^ Stanley, Alessandra (2008-03-14). "John Adams - Television - Review". The New York Times. 15. Jump up ^ Villarreal, Yvonne. "Entertainment entertainment, movies, tv, music, celebrity, Hollywood latimes.com - latimes.com". Calendarlive.com. Retrieved 2013-07-01. 16. Jump up ^ Tim Goodman (2008-03-14). "John, we hardly knew ye". SFGate. Retrieved 2013-07-01. 17. ^ Jump up to: a b c d Jeremy Stern (2008-10-27). "History News Network". Hnn.us. Retrieved 2013-07-01. 18. Jump up ^ Ira Stoll, "Bring Forth the Tar and Feathers", The New York Sun, March 11, 2008. 19. Jump up ^ Douglas Linder, The Boston Massacre Trials, JURIST, July 2001 20. Jump up ^ "Carpenters’ Hall". Carpentershall.org. 1995-07-04. Retrieved 2013-07-01. 21. Jump up ^ John Ferling, John Adams: A Life, Amer Political Biography Press (January 1997) p. 127. 22. Jump up ^ David McCullough, John Adams, Simon & Schuster, 2001, chapter 2. Part 2, 1:25:37. 23. Jump up ^ The Knox Trail History, New York State Museum website 2008 24. Jump up ^ "Health and Medical History of President John Adams: Smallpox Inoculation in 1764". Doctorzebra.com. 2013-03-05. Retrieved 2013-07-01. 25. Jump up ^ Blinderman, A. John Adams: fears, depressions, and ailments. NY State J Med. 1977;77:268276. Pubmed. [a] pp. 274-275 26. Jump up ^ David McCullough, John Adams, Simon & Schuster, 2001, pg. 186 27. Jump up ^ "John Jay's Treaty". Future.state.gov. 2000-12-23. Retrieved 2013-07-01. 28. Jump up ^ http://inaugural.senate.gov/history/chronology/index.cfm 29. Jump up ^ "1797 – The Inauguration of John Adams | The Sheila Variations". Sheilaomalley.com. 2004-02-16. Retrieved 2013-07-01. 30. Jump up ^ Olson, James S. (2002). Bathsheba's Breast: Women, Cancer, and History. The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-6936-6. 31. Jump up ^ David McCullough, John Adams, Simon & Schuster, 2001, pg. 627. 32. Jump up ^ "HFPA - Nominations and Winners". Hollywood Foreign Press Association. 2009. Retrieved 2009-01-11. 33. Jump up ^ "AFI Awards 2008". American Film Institute. 2008. Retrieved 2008-12-29.