Geoffrey Chaucer * The Nun's Priest's Tale

advertisement

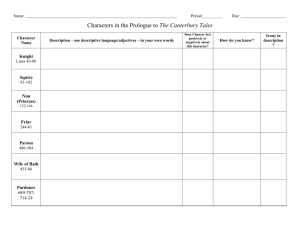

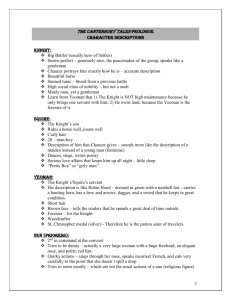

1 Geoffrey Chaucer – The Nun's Priest's Tale -When we study Chaucer, it is imperative that we carefully consider the epistemological conceptions of art. -Phillip-Sydney declares that the province of art must delightfully lead men to virtuous action. In other words, the principle function of art is that it must be didactic. General Information on the Canterbury Tales -The Canterbury Tales is a collection of tales, loosely linked together, and apparently narrated by a variety of storytellers, who not only have varying and differing character traits, but also belonging to different social strata. Chaucer imagines a group of pilgrims, setting off from the Tabbard inn in London, one spring on the long journey to the shrine of Saint Thomas Beckett in Canterbury; a journey that on horseback, would take about four days. To make time pass more pleasantly, they agree to share stories with each other. In the general prologue which opens all the tales, Chaucer gives us prolonged descriptions of the characters, which is revelatory of the characters' vices and virtues. There is, however, no description of the Nun's Priest, and the only way we can discern his character is by carefully analysing and explicating the account of his story. The Nun's Priest's Tale in Context The host in charge of the tale telling is Harry Bailey. When the monk begins his tale his efforts at entertaining the pilgrims are so miserable that the knight cannot prevent himself from intervening. In his cell, the monk has copies of 100 tragedies and before the knight interrupts and stops him, he is approaching the end of his seventeenth tragedy; the first one began with the fall of Lucifer. Harry Bailey, in agreement with the knight demands that the monk change his story; he refuses, and they implore the Nun's Priest to tell a tale. The Genre of the Nun's Priest's Tale 1. By definition, The Nun's Priest's Tale is a beast fable. This is one of the most popular forms of stories in the middle ages. These are stories about animals, which are the embodiments of typical human qualities. Cautionary anecdotes are brief. These fables carry only one simple moral. Chaucer however, not slavishly imitating the simple beast fable, emulates that form to accommodate complex meanings. 2. Some of the preoccupations of The Nun's Priest's Tale; - It is a romance about nobility and courtly love. - It bears a rhetorical debate over the significance of dreams. - It examines Christian misogyny. - It conflates other genres with the form of the beast fable. - Chaucer crafts his tale in this manner because without a fixed moral, one can gain insight into the complexities of human nature. 2 The Many Preoccupations of the Nun's Priest's Tale Many critics have suggested that a Chaucer tale exploits the nature of its genre but also draws attention to the ideological biases and exclusions inherent in the genre. In my opinion, the Nun's Priest's Tale is a wonderful, perhaps even the best example of Chaucer testing the bounds of his chosen genre- In this case, the beast fable. The beast fable is obviously a tale about animals, but one where animals are used as embodiments, or caricatures of human virtues, vices, prudences and follies, and the other typical qualities of mankind. In this sense, even the beast fable is didactic. Beast Fables are generally brief, cautionary anecdotes that use the obvious resemblance between man and animals to paint a moral and push a proverb home entertainingly. After all, as Phillip-Sydney says, the province of art is to delightfully lead men to virtuous action. Chaucer can be seen to exploit the nature of the beast fable fully in The Nun's Priest's Tale. It contains all of the traditional elements previously mentioned: the central characters are the chickens, Chauntecleer and Pertelote, and Russell the fox. The culpability, gullibility, guile and boastfulness of the characters are examined; the tale itself is brief, approximately 650 lines, and several morals are offered. The tale is also entertaining, but not only because of its caricatures of human traits. The tale contains numerous subgenres, such as the romance, rhetorical debate and Christian misogyny, and it is the interplay of these subgenres with the framing beast-fable that creates much of the human interest. The whole tale, therefore, consists of an ostensible outer-structure within which there is the interplay of numerous literary processes. In The Nun's Priest's Tale, Chaucer demonstrates some of the worst excesses of popular medieval traditions by putting them into context with his animal characters. The incongruity of a chicken taking part in a debate on the significance of dreams, for instance, is inherently comic but does not just imply the questioning of the value of rules of such debates. It also reveals the stresses that the beast fable undergoes when complex human ideas are introduced. Beast fables offer the most closed system of stereotypes available to a storyteller, but stereotypes, by their very nature are biased, exclusive, overblown representations of humanity- perhaps not useful for gaining a better understanding of a working system of morality. Certainly once Chaucer has introduced a level of non-stereotypical complexity into the tale, one simple, obvious moral is no longer possible, which raises a significant doubt about how useful it is to try and make moral points through such tales. Life is, after all, never one-dimensional or unilateral. It is for this reason that I think Chaucer is drawing attention to two types of vices and exclusions in The Nun's Priest's Tale. He examines those biases within popular medieval traditions through the introduction of subgenres which conflict with the apparent simplicity of the tale. By doing this he also exposes the biases of the beast fable form, which are largely made apparent through the multiplicity of “often conflicting” morals that the introduction of the subgenres create. We need to explore how these two ideas intercept. Many critics have suggested that the Nun's Priest's Tale does not so much make true and solemn assertions about life as it tests truths and solemnities. In my opinion, there are three main subgenres that Chaucer tests in his tale. The romance (with its emphasis on nobility and heroism), courtly love and Rhetorical debate address the topics of the significance of dreams, the free will versus the predestination debate and the use of exemplar and auctorizates, and lastly, Christian misogyny. The tale begins solemnly enough, with its description of the “povre wydwe” (2821) and her “narwe cotage” (2822) but as soon as we are introduced to her cock, Chauntecleer, the fun through the comic element begins. We begin with the romance, a genre traditionally featuring noble knights and their love-ladies, and hardly anyone else at all. The first information we have about Chauntecleer is that “In al the land, of crowyng nas his peer.” (2850). This is a perfect opening for a romance in which the heroic central character is usually introduced as the best of all its kind. However, in this context, the description parodies and pokes fun at the heroic tradition on two counts: “crowyng” is not heroic, and it is not particularly astonishing that 3 Chauntecleer does it well – it is the natural things that roosters do. Here we have the first clashing confluence of sub-genre, the romance and the beast-fable comically meeting. The tale moves on to describe Chauntecleer, using a classic descriptive technique of a poet-lover. The cock is described from head to toe with the illuminating colours of jewels and flowers. It is ludicrous when it is applied to Chauntecleer because it is usually used to describe a beautiful young maiden. Ironically, however, the description fits Chauntecleer perfectly, evoking the vainly strutting beauty of this beast. The fact that this kind of heraldic reductive description can be used successfully on a rooster highlights its formulaic use in the romance by foregrounding the technique- making the formula seem almost more striking than the description. Chaucer, by ridiculing formulaic patterns, is extolling poets who create an idiom of their own. He is not being victim of conventional form, and is thus original in his work. Then we meet the other chickens in the run, Chauntecleer's “sustres and his paramours” (2867), particularly Pertelote. Chaucer's invocation of the incestuous nature of the chicken run makes the very idea of courtly love seem ridiculous. And yet we are told of Pertelote that “syn thilke day that she was seven nyght oold that trewly she hath the herte in hoold of Chauntecleer, loken in every lith.” (2873 – 2875) The comedy of people falling in love at seven days of age pokes fun not so much at Chauntecleer and his dame, but at the whole convention of love at first sight. The use of romance conventions is comic in this tale because they violate the accepted rules. It is this incongruity that the breaking of expectation creates an awareness of the usually exclusive nature of romance conventions. Perhaps Chaucer is also ridiculing the exclusive nature of medieval society. Returning to the point of romance conventions, the courtly behaviours and refined pretentions of Chauntecleer are constantly betrayed by the ludicrous activities of and the ignoble motives contingent upon chicken nature. Chaucer never lets us forget that these chickens really are chickens- they peck, they are incestuous, and they are not nobly born knights or ladies, as we would expect romance characters to be. Of course, the opposite is also true; we also discover exclusion in the beast tale. When the narrator fails to regard the animal rights to human role and consistently turns them back into animals, it becomes apparent that those usually excluded from a beast fable are animals. Having set the tone of ironic rule-breaking, the tale moves on to a more serious satire and rhetorical debate, this is also its target. It is deeply ironic that Chaucer can successfully enclose so much of the syllabus of a 14th century university within the narrow and humble compass of the chicken run. The satire begins when a debate on the topic of the significance of dreams is sparked by Chauntecleer's fright at a dream. Pertelote begins by claiming dreams are meaningless; “Nothyng, God woot, but vanitee in sweven is.” (2922) this, she says, is according to the authority of Cato. “Lo Catoun, which that was so wys a man,” (2940) and hence Chauntecleer should not be so cowardly about his dreams. Chauntecleer retorts with the contrary view that dreams can be a “warnynge of thynges that shul after falle.” (3132) He argues this at great length, outclassing Pertelote's single auctorizate by naming authorities ranging from saints, to great philosophers, to the bible, and the classic period, and by categorizing dreams and slotting them into water tight compartments in medieval traditions. Medievalists were inclined to categorize dreams, and every type of dream was classified under these categories. The nine dreams either described or mentioned in The Nun’s Priest’s Tale fit into one of these categories or include elements from the other categories. The categories are; Somnium = symbolically enjoins beforehand what is to ensue in the future. Insomnium = does not foretell the future in a symbolic way; instead; it recounts the dreamer’s current preoccupations in life and can be caused by mental distress or physical conditions forced by overworking or overeating. Visio = prophesises the future in a dream exactly as it will happen. Oraculum = foretells the future through a figure in the dream who will describe the dream and will advise the dreamer how to avoid it. Visium = does not foretell a dream; instead; when the sleeper is half awake and half asleep, they see shapes around them – nightmares fall into this category. 4 Chauntecleer continues to cite also two lengthy supporting exemplar and makes passing reference to several more. He cites authorities such as Macrobeus, Daniel, Joseph and St. Kenelm. Through the sheer mass of his evidence, he wins the argument. However, he uses his precedents only to prove the contrary of what someone else has argued, rather than to master his primary experience and interpret it in the context of his own circumstance. Philosophical abstractions are undisputedly elevated and intellectually edifying in this tale; nevertheless, if they are intangible and indefinable, in terms of material human experiences, and if they do not subserve rational thought and experience, they become mere evaporations on the subject. Having argued that his dream presages “adversitee,” Chauntecleer blithely ignores his own conclusion. One may ask the question, “Why does he ignore his own premise?” and “What was the point of the debate if it was not to discover whether or not Chauntecleer, in his predicament, was in genuine danger?” The arguments used by Chauntecleer and Pertelote, irrelevant as they may turn out to be, are not in themselves invalid; they are merely inapplicable to a situation which involves a natural predator and his prey. Through the debate between Chauntecleer and Pertelote, either Chaucer, or the narrator, or the Nun's Priest, somewhat amusingly illustrates that learned rhetorical debate, and although it is powerful, it is not conclusive. It requires proper application to be useful; but improperly applied it can be a bully's tool. Again, Chaucer reveals the inadequacies of using animals to discuss certain human issues; he exposes the bias inherent in the beast fable genre: reason is useless by its very nature to beasts. Also, reason not tempered by humility can result in an unfortunate fall. Despite having all the correct logic at his wingtips, Chauntecleer fails to interpret his dream correctly and flies down from the safety of his beam. It is this action that makes the confrontation with the fox possible. The descent from the beam is represented by Chaucer as a pivotal action in the tale, and raises the question as to why this fatal moment occurred. In an attempt at explication, the Nun's Priest makes a series of rhetorical comments on the popular medieval debate of free will versus predestination. The entire range of the debate is condensed into two contradictory homilies: that Chauntecleer was “ful wel ywarned by thy dremes,” (3232) of danger; warning in his dream implies that he could have changed his fate; simple or conditional necessity means that Chauntecleer could not have avoided his fate anyway “but what that God forwoot moot nedes bee” (3234). Alluding to St. Augustine, Boethius and Bishop Bradwardine, concerning the contradictory homiletic stance on freewill, foreknowledge and foreordination, is not the end of it. The Nun’s Priest alludes to an old debate which had returned with force to the foreground of 14th century consciousness – whether God’s foreknowledge (“forwiting”) is consistent with human freewill. If God knows what is to ensue, is it possible for humans to act freely, without compulsion from God? Most often sited on the issue was St. Augustine, who in his later years argued that human freewill was essentially illusory, compared to God’s power and omniscience. Chaucer faces the question when he later discovers Boethius, who argues, in modification of St. Augustine, that just as hindsight cannot alter the way people act, so God’s foreknowledge does not affect a person’s freewill, although God exercises a providential control for good over the sum of human events. Of the English contributors to the “altercacioun” the most well known is Sir Thomas Bradwardine, to whom Chaucer alludes in his tale, Bradwardine in his treatise ‘The Case For God’ takes the same line of argument as St. Augustine and counters contemporaries who said it was man’s will, not God’s, which determines the course of events. Chaucer discusses this controversy, through the voice of the Nun’s Priest. As if enough confusion has not already been fuelled through contrary possibilities being equalised and held in unresolved opposition, the Nun's Priest offers further explanations “if I conseil of wommen wolde blame” (3261). He implies that it was not destiny or free will but Chauntecleer's wife's as well as Venus’s fault that forced the meeting between Chauntecleer and Russell the fox. Philosophical abstractions on the subject of predestination and free will are indeed elevated and intellectually edifying. Nevertheless, if they are intangible and indefinable, in terms of material human experiences, they become mere evaporations on the subject. When a mirror is held at shifting angles to a welter of contradictory ideas, and when those contrary possibilities inherent in them are equalised, the result in the Nun's Priest's words are “but I ne kan nat bulte it to the bren” (3240). 5 “If I conseil of wommen wolde blame.” (3261) this is rather an amazing array of words, energy and theory to expand on the fact of one fox lurking in a cabbage patch. One has the right to ask whether it has a point, and if it does what might it be? After all, this meeting between Chauntecleer and the fox is not even fatal. I think perhaps the cruces of the Nun’s Priest’s rhetorical display are to point out the futility of arrogant theoretical abstraction in the face of sudden natural danger. Perhaps Chaucer is satirising the whole idea of knowledge and its pursuit for its own sake. The Nun's Priest hints that what humans live with, on the one hand, is a continual stream of chaotic facts and incidents, and on the other, is an impulse which so delights the heart, an impulse which is too organised and explained. By means of his satire Chaucer further intimates that the chaos we face provides delightful opportunities for freedom totally absent in the pedantry of theories. The bias of explanatory philosophies thus becomes clear. Philosophies generally assume that explanation is possible, and relevant. Even if it is possible, the unflinching question we can pose is whether or not it is relevant to try and explain a cock's free will, or the lack of it, when cocks, after all, are creatures of instinct rather than reason. Chaucer obviously re-agitates the point that addresses the problem of conflating humans with animals. Obliquely, once again he satirises the purport of the beast fable. Chauntecleer however, is so much his own person within the tale that whether or not his representativeness and purpose is problematical is no hinders not our enjoyment of the tale. Another trope that appears throughout the text is misogyny, and as is customary in medieval literature, it is consciously linked to Christian doctrine. The first occasion on which we have a hint of such misogyny is when Chauntecleer belittles his wife’s opinions concerning dreams, which he concludes with a veiled insult containing a reference to Genesis (3164) “Mulier est hominis confusio- Madame, the sentence of this Latyn is, 'womman is mannes joye and al his blis.'” Chauntecleer here clearly insults Pertelote's intelligence. Misogyny against women is not restricted to the Old Testament only; St. Paul, in two of his epistles. Reagitates this matter and conclusively deems a woman inferior status. In First Timothy: 2:11 – 12, he declares that he will “suffer not a woman to teach, nor to usurp authority over the man, but to be in silence.” She must “learn in silence with all subjection.” Pertelote completely violates this decree when her imperatives clearly command Chauntecleer to take her advice. The Nun's Priest here is obliquely tongue-incheek, for Chauntecleer's wisdom, as we will discover, is no wiser than Pertelote's wisdom. Chauntecleer tells Pertelote, “In principio, mulier est hominis confusio,” and mistranslates it to her as the exact opposite of its true meaning- “womman is mannes joye and al his blis.” His use of a flattering, malicious mistranslation is somewhat ironic, as flattery is his own undoing when he meets Russell the Fox. Here again, misogyny is addressed tongue-in-cheek. The height of Christian misogyny in the text is, however, expressed through the words of the Nun's priest; which is ironically appropriate, as he is a 'henpecked' cleric with a female superior. His status in itself is repugnant to the Pauline position, that women must be subjected to men. This “henpecked” cleric tells us “My tale is of a cok, as ye may heere, That tok his conseil of his wyf with sorwe, to walken in the yerd upon that morwe That he hadde met that dreem that I yow tolde. Wommennes conseils been ful ofte colde; wommannes conseil broghte us first to wo, And made Adam fro Paradys to go,” (3252 – 3258). It is futile to beat around the bush with polite mutterings about inconsistency; the whole statement cited above is a lie for two very pertinent reasons. Firstly, Pertelote's “conseil” was to take “digestyves of wormes, er ye take youre laxatyves” (2961 – 2962) – counsel Chauntecleer most certainly does not take. Secondly, Eve did not give Adam any counsel; she simply gave him an apple. The fault of the man, The Nun's Priest here is attributing to the woman. This extreme antifeminist statement is made in a tense middle-section of the tale, after the character development and satire of the opening section, and before the climax of the fox-chase and escape. Because of its central placement, it could be read as the moral linchpin of the tale. We are compelled to ask why this misogynist statement is given such emphasis. I am inclined to believe that it has to do with the fact that there are only two main human characters featured in this tale; the widow who owns the chickens, who is fully a part of the story, and a perfect exemplum of noble poverty and non-threatening sexuality: a 6 stereotype. But the Nun's Priest, a real person, has his own agendas, vices and learned responses, and his tale reflects these. At this point in the tale, the inner conflict of the misogynist appears for a moment on the surface; then it is pushed back behind the artifice of the story, where it has been operating secretly all along. Chaucer is using metafiction to expose another bias in the beast fable genre- the moral of the tale can be subsumed, either consciously or unconsciously by the teller. This is how the form of the fable is used, as much as its traditional component parts that define its usefulness and its morality. The Nun's Priest's personal bias presents us with the image of a sinful female chicken, who causes the fall of the noble cock. But chickens surely, cannot be sinful. One can, for instance, imagine the Widow's reaction if her cock suddenly began to practice a chaste and abstentious monogamy. Through exploring the subgenres of the romance, rhetorical debate and Christian misogyny, Chaucer here throws new light on the biases and exclusions inherent in each of the subgenres he uses in The Nun's Priest's Tale. But he does more than this. The conflict between the subgenres and the beast fable results in a multiplicity of possible morals, none of which is obviously the moral of the tale. This makes a traditional reading of the tale (as a beast fable with one explicit moral upon which the tale is built) problematic for the discreet, highly critical and ideal reader. When contrary possibilities are equalised and held in unresolved opposition, because of the ambiguity that ensues, we will be teased out of thought. It appears that The Nun's Priest's Tale has been an opportunity for Chaucer to enter into the literary conflict concerning the use and value of the fable form. I believe that amongst other issues, in this tale Chaucer is highlighting a fundamental weakness in the beast fable form through his use of multiple morals. We become aware of the problem when we are told to “taketh the moralite,” (3440) without being given any solid evidence as to which moral we should consider. The traditional form of the beast fable has only one, very obvious moral... In The Nun's Priest's Tale, however, we have at least ten to choose from, many of them contradictory. This is not atypical of Chaucer if we consider his technique as represented by the tales as a whole, which is essentially comic; he encounters authority, whether it is classical or literary, with the fracturing and multiple perspective of comedy. The notion that any action, however simple, can lead to one and only one moral judgement, is effectively exploded by Chaucer's ingenious expedience at describing just such an action and then drawing several contradictory morals from it. The list of possible morals is quite impressive; “Nothyng, God woot, but vanitee in sweven is,”(2922) “Mordre wol out; that se we day by day,” (3052) “That many a dreem ful soore is for to drede,” (3109) “In principio, mulier est hominis confusio-,” (3163-3164) “Womman is mannes joye and al his blis,” (3166) “For evere the latter ende of joye is wo,” (3205) “Wommennes conseils been ful ofte colde,” (3256) “Wommannes conseil broghte us first to wo,” (3257) “For that he wynketh, whan he sholde see, Al wilfully, God lat him nevere thee!” (3431, 3432) “God yeve hym meschaunce, that is so undiscreet of governaunce That jangleth whan he sholde holde his pees,” (3433 – 3435) “Lo, swich it is for to be recchelees And necligent, and truste on flaterye” (3436, 3437). None of these morals is necessarily true when taken out of context, but they are truths in the light of the case to which they are attached, and offer man the hope of a freedom which bypasses the tautology of logic. Chaucer exposes the inability of a beast fable to deal with complexities, and its usual exclusion of such complexities; nevertheless, he keeps its usual form intact. This poses the question whether or not the beast fable should be abandoned altogether or whether there is some other value inherent in these questions which is the possibility that antinomies meet in one. That, however, does not violate the nature of the tale itself which entertains contrary possibilities, equalised and held in unresolved opposition. Perhaps we should take a closer look at what the Nun's Priest says in his conclusion. It would appear that he is not actually addressing all good men with his didacticism, and advising them about considering the morality of the tale. “But ye that holden this tale a folye, As of fox, or of a cok and hen, taketh the moralite, goode men.” (3438 – 3440) 7 Perhaps Chaucer is subtly suggesting that readers should be privy to choose what they consider is valuable in a tale rather than be herded into accepting the univocal, potentially inapplicable moral of a standard beast fable. However, I would argue that The Nun's Priest's Tale is too accomplished, extremely refined, pruned and polished and far too entertaining a tale for it to be branded as an account expressing entirely negative sentiments concerning the beast fable genre. What I perceive is, Chaucer is not only making the limits of the genre apparent, but he is also explaining the potential of the genre when it’s at its best. While exploiting the nature of its genre, The Nun's Priest's Tale also draws attention to the ideological biases and exclusions inherent in the genre. The popular medieval traditions of the romance, rhetorical debate, and Christian misogyny are examined in relation to the beast fable, and are found to have comic excesses and biases in their method of telling. The ultimate meaning of The Nun's Priest's Tale is debateable for these reasons, which casts doubt on the beast fable's usefulness as a tool for teaching moral truths. Nevertheless, even without a fixed moral, we do gain some insight into the complexity of human nature. 8 The High Watermark of The Nun's Priest's Tale In the prologue of The Nun's Priest's Tale, the interruption by the knight calls for something more in literature. If not a correction of the view of fortune in its relations to the law of the prime mover such as he himself has already presented in his tale of Palamon and Arcite at least an amplification of a view of life which allows for quite another way of fictive presentation “whan a man hath been in poure estaat, and clymbeth up and wexeth fortunat, and there abideth in prosperitee Swich thing is gladsom, as it thynketh me, and of swich thyng were goodly for to telle.” (2775 – 2779) To this the host gives scolding ascent. The point of view may not be that of the knight, a representative of quite another class of society, but the host does not know that what he has heard from the monk has become a heavy burden to the mind, if not an outright bore “for sikerly, nere of youre belles that on youre bridal hange on every syde, by nevene kyng that for us all dyde, I sholde er this han fallen down for sleep, althogh the slough had never been so deep.” (2794 – 2796) And so the knight and host are united in common intention if not in comprehension of the issue at hand. Both have objected to the performance of the monk, the knight we presume because he objects to the statement of a not entirely sound view of life, for life is a confluence of contrary principles, both painful and pleasurable and because if we may judge him from the story he has told, and because “for literl hevynesse is right ynough to much folk, I gesse.” (2770) The host objects because there is “no desport ne game,” (2791) in these tales, and furthermore the reiterated tragic theme has become monotonous. Both views have their healthy perspective because this is a tale of contrary possibilities, where antinomies can inhabit the tale's preoccupation comfortably. The monk, however, had had his say, and declines to relate a tale of hunting; his natural discretion, which has held him back from engaging in badinage with the host, once again urges his private life to himself. We turn instead to another religious, “This sweete preest, this goodly man Sir John,” (2820) who is urged to tell us a happy, cheerful tale. His horse, a jade “bothe foul and lene,” offers a contrast to the sleek berry-brown palfrey of the monk, whom the Nun's priest now supercedes. But as we read, we discern that the paucity and poverty of material goods in the Nun's Priest to not preclude a richness of natural gifts and a depth of cheerful goodness, absent from the performance of the materially endowed, self-limiting monk. For reasons which we can only surmise Chaucer has not given explicit details about the person and character of the Nun's Priest. Since Chaucer himself has told us little about the character of the Nun's priest, although some deductions may be made from the tone and attitudes of the task assigned him, critical opinion has perforce to be conjectural. One commentator describes him as “A handsome, strong, rosy-cheeked youngster with a sense of humour unequalled in the company.” This assumption is purely conjectural. The priest, however, can deftly satirise the personal characteristics and the literary style of his predecessor without for a moment arousing the suspicion of his dignified superior. Another commentator suggests that he is “scrawny, humble, and timid, while well educated, shrewd and witty, weak in body and fawning in manner. “ Even in the conjecture, the tale allows for contrary possibilities. These are tantalising surmises; in the end, however, each reader will feel that the personality of the Nun's priest is best derived from an examination of the story Chaucer chooses to assign him. As we have said, the Nun's Priest masterfully integrates many elements which we would have encountered singly or in combinations in the other tales. More important, perhaps, than these elements addressed one by one or in combination is the priest's creation of a frame or envelope which contains a moral and quasimythic structure. The Nun's Priest, therefore, through his pruned intellect, creates a complex narrative. He is not only a sharp intellect, but he can also narrate a story with great efficacy. This outer frame presents to us these human agents necessary to provide for the reader some idea of human behaviour, some rule of continence and contentment. The old widow, with her little cottage and her careful economy by which she provides for herself and her two daughters, offers by such details as temperance of diet and exercise and a contented heart an image of temperate law of self-restraint and self-control, of sobriety and reasonable discretion. It is the widow's yard that is the world, apparently safe and secure for Chauntecleer and his wives; it is into this world that evil intrudes in the shape of the sly fox; it is to this world that the widow wishes to restore Chauntecleer at the conclusion of his adventure, setting in motion, in mock epic fashion, the final boisterous chase and attempt at rescue. 9 At this point in the poem or the tale, however, it is Chauntecleer's plight that holds our interest, and for which the ostensible outer human frame exists. It is Chauntecleer's character and his virtues or absence of virtues, his self-assurance, and braggadocio, his pride, his sensuality, his susceptibility to flattery and his sly intelligence that engage our minds. “His coomb was redder than the fyn coral, And batailed as it were a castel wal; His byle was blak, and as the jeet it shoon; Lyk asure were his legges and his toon; his nayles whitter than the lylye flour, And lyk the burned gold was his colour.” (2859 – 2864) This description is analagous with the manner in which epic heroes are depicted. The description of Chauntecleer is very similar to the description of other epic heroes. Chauntecleer embodies the idyllic cock. If we compare him to the oldest English epic Beowulf, we find that Chauntecleer's boast vastly differs to Beowulf's boast. Chauntecleer's boast is not that of declaration of war, where he intends to kill a villain, but his actual crowing. It was his duty to raise the sun each morning, giving birth to life on Earth. Chauntecleer's intelligence is for the purpose of proving the irony of man's own inflated views of himself. Interestingly, his intelligence is juxtaposed with his susceptibility to flattery, that is, when Chauntecleer refutes Pertelote's notion that dreams are without relevance to daily life, he speaks in such a scholarly and philosophic tone that one can hardly believe it is the voice of the rooster. ““Madame,” quod he, “graunt mercy of youre loore,” (2970); ... “By god, men may in olde bookes rede of many a man moore of auctorite,” (2974, 2975)... “Lo, in the lyf of Seint Kenelm I rede... Of Mercenrike, how Kenelm mette a thyng.” (3110, 3112) Then, there is the old testament, which he claims is a manual well worth studying; he alludes to lord Pharaoh, king of Egypt; he employs profound theological and philosophical references, in the context of a barnyard to parody humanity as well as the heroic epic tradition. The opening description of Chauntecleer replete with instinctive passion and associations of poverty and patient, passionless temperance of the widow. We must bear in mind that the widow’s poverty is not by choice. Not a selfsacrificial vow of abstinence from worldly pleasures. Style itself, echoes the contrast between Chauntecleer and the widow. As Chaucer begins to employ the language of romance, what is austere, or even pedestrian in the opening of the widow’s tale gives way to something courtly, and perhaps something descriptively elevated with even momentary flight into lyric “In sweete accord, “My lief is faren in londe!”-” (2879) The language attributed to Chauntecleer may be considered the high style in keeping with the poet’s intention to parody the purely tragic view of the world, and to supply a corrective through the device of comedy. Tragedy can never be purely devoid of comedy, and comedy, conversely, cannot be free of tragedy, for life is a confluence of contrary possibilities, hence the necessity for enhancing the character of the cock, so that he may appear to be regal, hence the fall from good fortune, hence the philosophical rumination about the relation of will to necessity, and freewill to foreordination, the elevated speeches, apostrophes and exclamations, the comparisons with figures of classical antiquity, and hence the errors in judgment and the final moral tag. The subjects and mannerisms of tragedy must be present, even in ironical contexts, seen in contrast to the subjects and mannerisms of comedy. After all, one's earthly existence is a confluence of contraries; pain and pleasure, joy and sorrow, black and white, gold and silver, and so on. In like manner, in a world of love and marriage we encounter domestic quarrelling, life is a conglomeration of charms and vices, of deception and jokes, of personal arrogance and instinctive passions, of personal vanity and wishing to be right at all costs, of wit and hair-breadth escape, of chases and rueful laughter. Contraries must exist if an artist is to present a saner and more humane attitude than the one stated by the monk. Therefore, the Nun's Priest trumps the monk, the man who clearly works by wit and not by witchcraft. A large section of the tale is composed of the debate between Chauntecleer and his beauteous paramour, Pertelote, on the subject of dreams. Their rhetoric reveals a great deal of their character; Pertelote's lines beginning “”Avoy!” quod she, “fy on yow, hertelees!”” (2908) with their repeated exclamations and questions are full of feminine excitability and concern [Chaucer clearly attributing exclusive character traits to the feminine gender]. Her admonitions are purely domestic “For Goddes love, as taak som laxatyf.” Her wisdom is for the most part, the wisdom of the home dispenser. Chaucer seems to clearly enjoy the game, 10 and he projects his subtleties through the Nun's Priest. Chauntecleer's long-winded answer, beginning with an elaborate politeness, “”Madame,” quod he, “graunt mercy of youre loore.”” (2970) is a rejoinder of some haughtiness of tone. More than a refutation answering the alleged authority of Cato, the long recital of superior authorities allows us to see Chauntecleer as one of Chaucer's more self-conscious avatars. More thoughtful, more playful and sly, more pompous and self- assured, but not necessarily wiser, although highly knowledgeable. The cock is a narrator of no mean skill. Constructing his two initial exemplar with great care as to form and tone and attention to detail; “Oon of the gretteste auctour that men rede seith thus: that whilom two felawes wente...”, (2984, 2985); “and certes in the same beck I rede;” [of] “Two men that wolde han passed over see,” (3064 + 3067). Indeed, he is so careful a constructor of plot with the inevitable conclusions that the moral statement with which the first one closes tends to overshadow the principle concerns with the credibility of dreams: “O blisful God, that art so just and trewe, Lo, how that thou biwreyest mordre alway!” (3050 + 3051). This skilful rhetorician, Chauntecleer, engrossed in rebutting Pertelote's accusation of indigestion being the cause of his farfetched dream, loses track of the purport of his exemplar on the meaningfulness of dreams except insofar as they aid him in defying her stance on the purging power of laxatives. It detracts him from safeguarding himself from a common sense practical truth that the prey must be vigilant of its predator. Helen Cooper sheds light on Chauntecleer's sexual prowess. She intimates that Chauntecleer’s sexual frustration is due not to an inconvenient husband but to the narrowness of his perch, and that his glorious promiscuity with his seven concubines is his undisputed function in life. Chauntecleer's sexual promiscuity triumphantly disproves the notion that it might be impossible to parody fabliau (an extended joke or trick, often bawdy, and usually full of extended sexual innuendo). The Nun's Priest's ability and subtle skill at summarising the potential of language, of style, words and text, attest to that which defies the conventional notion that it might seem impossible to parody fabliau. The point concerning dreams is made, first through a reluctant believer in dreams, and then through an actual nonbeliever who is proved to be wrong. The point that Chauntecleer is lured into Pertelote's way of viewing dreams hints at a henpecked husband. Despite his long philosophical discourse to which he warms up, and in rapid melange of instances drawn from biblical, literary and historical sources within a space of forty lines, he fails to substantively prove his position on dreams. He then rattles off six additional stories to refute his assertion with the most bathetic comical statement. “Shortly I seye, as for conclusioun, That I shal han of this avisioun adversitee; and I seye forthermoor That I ne telle of laxatyves no stoor, For they been venymes; I woot it weel, I hem diffye, I love hem never a deel!” (3151-3156) The action that follows upon this long debate, which is nothing more than an extended catalogue of other sources, in which each agent has but one major speech, bears out the prediction. But before the action ensues we have the intervention of his love-speech to Pertelote, bold and not subconscious, containing a joke at the expense of his less tutored wife: “in Principio, Mulier est hominis confusio- Madame, the sentence of this latyn is, Womman is mannes joye and al his blis”. Whether we cheer or blame Chauntecleer in this joke upon his wife-paramour, the speech is clearly that of the passionate lover, embellished with sincere regard expressing gratitude for God's grace, joy and comfort in her companionship, as well as that up surging confidence that enables him to defy dreams and vision. Of course, they have had their quarrel or debate; nevertheless, their relationship is a happy and natural one elevated by Chaucer through the language of love. The jest that Chaucer puts in Chauntecleer's beak hints at the double-edged truth to which the middle-ages were dedicated by tradition on the one hand, and by human nature on the other: Christian misogyny as well as its counterpoise that woman was the ultimate joy of man resided comfortably together. In the beginning of the scriptures, according to fundamental and traditional Christianity, Eve was the source of Adam's fall; and yet, Chaucer's humane and comic realism forbids the dour antifeminist implications and provides a counter-poise in that other truth, that other affirmation, ‘amor vincit omnia’ (‘love conquers all’). “For whan I feel a-nyght your softe syde-Al be it that I may nat on yow ryde, For that oure perche is maad so narwe, allas- I am so ful of joye and of solas, that I diffye bothe sweven and dreem.” (3167-3171) We see Chauntecleer in all his pride, hardly deigning to set his foot to the ground, royal as a prince in his hall, says Chaucer, summoning all his wives with a fair cluck, 11 “And with a chuk he gan hem for to calle, For he hadde founde a corn, lay in the yerd. Real he was namoore aferd. He fethered Pertelote twenty tyme, And trad hire eke as ofte, er it was prime. He looketh as it were a grym leoun, And on his toos he rometh up and doun; Hym deigned nat to sette his foot to grounde. He chukketh whan he hath a corn yfounde, And to hym rennen thanne his wyves alle. Thus roial, as a prince is in his halle,” (3174-3184). Up to this point, Chaucer’s narrative has supplied us with a situation which is to be fulfilled in the remaining part of the tale, along with some intellectual attitudes that are to be tested subsequently. Chauntecleer's pride has been placed before us not only on the details of his dainty high stepping and his grim lion's look, but also in the contest of his lengthy reply to Pertelote. Sustaining the principle of contrary possibilities, Chaucer here after plays against each other’s instinct and rational control. With the return to a purely narrative tone in lines 3187 and following, Chaucer appears to take a deep breath before introducing the catastrophe foreseen by Chauntecleer in his dream. In the midst of the beautiful May, when Chauntecleer's heart is full of “revel and solas” (3203) he is to discover that the latter end of joy is woe. Chauntecleer becomes crucial at this moment the Nun's Priest, raising the whole question of destiny and man's freedom as the catastrophe impends: the fox waits to fall upon the cock. At this juncture we have a burst of rhetoric in a variety of comic tones: the extravagant comic sublime (3226) (“O false mordrour... O newe Scariot, newe Genylon... O Greek Synon, that broghtest Troye al outrely to sorwe! O Chauntecleer...”) merges into a more arid statement of simple and conditional necessity, and finally into the traditional indictment. The simple necessity familiarises that God's foreknowledge constrains one by a simple necessity to do a thing. The indictment is as follows, “Wommenes conseils been ful ofte colde; wommannes conseil broghte us first to wo and made Adam fro paradys to go, ther as he was ful myrie and wel at ese” (3256-59). In the mouth of the Nun's Priest, such a statement is a kind of bold impertinence because we know that he is 'henpecked'. He is, however, one that works by wit and not by witchcraft, and therefore finds a way out by quickly wielding his impertinent statement to the narrative context (3252) “My tale is of a cok, as ye may heere, that tok his conseil of his wyf with sorwe, to walken in the yerd upon that morwe that he hadde met that dreem that I yow tolde.” Hence the narrator escapes the responsibility both for philosophical explanation and for the indictment of women. Although it is difficult for us as readers to impute how much involvement Chaucer himself effects within the tale concerning the indictment of women, with a degree of presumption we can attribute some indictment to the Nun's Priest. Chauntecleer has had his intellectual fun in deceiving his wife with a Latin tag; Chaucer has had the Nun's Priest offer us, in Chauntecleer's translation of the Latin, two definitions of love which threaten to cancel each other out (contrary possibilities continue to be sustained). Adam fell through Eve's counsel, and bequeathed to their children similar falls without number; yet in the relationship between Chauntecleer and his wife-paramour, there is a certain careless and lovely sensuality, a springtime “revel and solas,” an overtone of one strong tradition that sees the love of woman as a means by which man ennobles and perfects himself. It constitutes a perennially perplexing ambiguity which man's mind declines to resolve itself, even if it could. We move out of the romantic and sensual into the subject of mutability, into a commentary upon the turn of fortune' wheel, with which we have been bludgeoned in the previous performance. Man's reason-action is accommodated by the providentional plan in affecting the outcome of fortune. The joke becomes more serious, and the sarcasm is faintly antifeminist. The ambiguity with which the Nun's Priest makes his point makes him palpable, but in the familiar lives dealing with the opinions of worthy clerks on the problem of evil and the relation of God's foreknowledge to man's free will, the universal problem of the freedom of all humanity arises, and one feels that the priest is disinclined to provide a solution, “I wol nat han to do of swich mateere.” (3251) It seems strange such an intellectual priest should not know what he believes, and does not have a strong base of assertion. He toys with notions which he himself declines. This is a clever strategy of equalising contrary possibilities and then not resolving them. I am inclined to interpret this strategy as Chaucer's effort to be didactic, while not inflicting upon his readers any particular line of thought that he might entertain in his own mind. 12 But the context is comic and philosophical, once again subtly engaging in contraries. The elevation of Chauntecleer's fortunes to a level we expect of the epic and tragic has the obvious effect of comic incongruity and disproportion. The Nun's Priest's special task is to accommodate the mysteries of destiny and the order it pursues, dreams, Venus, nature and the rest to a divine foreknowing, which yet allows to man significant action and a saving self-knowledge. As the subsequent appearance of the fox makes clear Chauntecleer's original assertion concerning dreams was correct and Pertelote's was wrong: he will indeed, have adversity as a result of his dream. Seduced by the confidence which may be the fruit of love and following his wife's advice so far as to fly down from the beams, Chauntecleer makes obvious the difference between believing with conviction and acting upon that conviction. No matter how bad the advice of Pertelote’s, Chauntecleer cannot be exempt from the trials and temptations of his temporal existence and a reversal of fortune is often the result of being a failure under such trials and testing. Indeed, the trials and temptations are themselves the means by which the Christian comedy achieves its happy goal, the battlefield upon which the soldier’s mettle is put to the test. The test offered by the appearance of the fox is compounded by flattery and deceit, which in some measure balances out Chauntecleer's own flattery and deceit to his wife. In both deceptions there is that curious intermingling of instinctive self-preservation with soothing blandishing flattery. Both deceptions are successful, the foxes more obviously so inasmuch as Chauntecleer's bird nature itself conspires to supplement the fall; like his fathers and presumable ever rooster's before him, Chauntecleer's endeavours to match his forefathers singing necessitate the closing of the eyes. “Ah! Beware through the betrayal of flattery,” cries the priest, and in an instant, Chauntecleer is ensnared by his natural enemy. It is difficult to refrain from addressing the skill of the rhetorical pattern of complaint with “O destinee, that mayst nat been eschewed” (3338) and passing shortly to (3342) “o Venus, that art goddesse of plesaunce,”,(3347)”O Gaufred, deere maister soverayn,” and finaly to the capping, mock heroics of lamentation in (3369) “O woful hennes, right so criden ye.”, the quadruple outburst, drawing into fearful and wonderful juxtaposition comedy of situation with the inflated sublime of exclamatory closet tragedy. Whatever may be lacking in internal, unifying factors is more than adequately compensated by Chaucer's poetic effort to hold in delicate balance the humble matters of comedy with the elevated, the transporting, and the philosophical matters of tragedy. The poem draws to its closing act in a burst of vividly detailed activity. All that has been restrained, controlled, and elevated gives way in style and subject matter to the hectic demands of a chase. The serenity and moderate quietude of the poor widows household is dissipated in a flash by the spirit of the mobilised rescue, spreading like wildfire to ‘many another man’ and to the dogs and in further hectic sympathy, to the hogs, cows, ducks and geese, and a swarm of bees. Then, in a sudden move out of the excitement of the chase, the Nun's Priest closes in upon his moral goal in the colloquial and familiar tones of admonition; “Now goode men, I prey yow hirkneth alle: Lo, how Fortune turneth sodeynly, The hope an pryde eek of hir enemy” (3402-3404). The reversal of Fortune, by which Chauntecleer's native wit brings about his escape, gives us some clue as to the relation of man's reasonactions to the providential plan. The flattery by which he himself deceived his wife is superceded by that of the fox; now again the laying on of flattery and praise for the sake of personal safety wins the cock his freedom; the foxes last attempt with unctuous and specious humility to win back his loss is deservedly unsuccessful, and Chauntecleer's answer to his enemy is a famous locus in Chaucerian moral statement: ””Thou shalt namoore thurgh thy flaterye Do me to synge and wynke with myn ye; For he that wynketh, whan he sholde see, Al wilfully, God lat him nevere thee!” “Nay,” quod the fox, “but God yeve hym meschaunce, That jangleth whan he sholde holde his pees.” Lo, swich it is for to be recchelees and necligent, and truste on flaterye. But ye that holden this tale of a folye, as of a fox, or of a cok and hen, Taketh the moralite, goode men” (3429 – 3440). The Nun's Priest's Tale raises the questions of humour, responsibility and destiny in the manner of a tragedy or a moral romance but dismisses them as a kind of impertinence in favour of men's ability to learn from daily experiences, in the manner of an ironic comedy. Its subject matter is a weighing of two sides of the ledger of man's serious and comic interests, 'contrary possibilities.' A host of questions is set in motion, in the context of domestic and destinal. Insofar as the questions can be confronted, they challenge the facile view of tragedy set up by the monk. The answers, insofar as they are provided, are couched in the 13 terms of ironic errors in judgement, from these errors flows self-knowledge. And about chance, or love or destiny, the least said the better. One level of the meanings in the Nun's Priest's Tale can be described by the word 'quizzical'. They arise out of the complex picture of man seen as wilful and self-loving; yet amiable and capable of loving others (contrary possibilities). Created in the divine image, but somehow all too human; responsible for his actions; yet controlled by forces beyond himself to assert that man is free and at the same time that he is not is in effect to make us accept both assertions as true. To offer the view that love yields joy and then that it offers sorrow, or to hold in balance the philosophies of Boethius and Bishop Bradwardine with a world of laxatives and remedies for ague, is in essence to concentrate our gaze upon the disparities in the experiences of fallen men and to confess to a certain helplessness in the human condition. On another more accessible level of meaning we encounter the ironist's pronouncements to those who must pick their way through the obstacles of life: Beware of flattery which destroys self control, blinds us to what we must see, and loosens our tongues when we should be silent. The lesson spoken by cock and fox at the close of the poem is of expedience in which there are errors in judgement, flattery, negligence, lack of governance, and an uneasy acceptance of another. Whether the promulgator of these pedestrian truths is the inscrutable Sir John pronouncing so knowledgeably on life and love or Chaucer speaking through a mask is immaterial. What we know with certainty is. A sane hope pervades them. The hope for rational creatures accepting the appalling truth of their day-to-day responsibility within a rational universe is devoutly wished. The final plight of Chauntecleer demonstrates the relation of instinct to rational control, of thoughtless vanity to presence of mind, of foolish pride to a just humility, the happy ending with the rivals standing “hand-in-hand”, so to speak, reciting what wisdom they have achieved, reveals some truths in miniature, truths mundane and pedestrian, but truths nonetheless. What we have then is a poem that addresses the presence of contrary possibilities in human experience, without ever testifying of predilection for one possibility over its counter-poise. 14 The Character of the Nun's Priest The Nun's Priest's story of the regal Chauntecleer and the lovely dame Pertelote is the lightest and the most widely known sections among the many stories narrated in The Canterbury Tales. Indeed then the Nun's Priest is an outstanding storyteller. Many critics have hinted and realised that this tale skilfully reflects facets of its teller's character; nevertheless no-one has made an attempt to delineate in detail just what sort of person Chaucer intended his audience to visualise as the Nun's Priest. Since Chaucer did not include in The General Prologue a portrait of this pilgrim, whatever view one takes of the Nun's Priest must be based on the comments to and about him by the host, on his own short comment to the host, on the narrator's brief remark about him, and on the superb tale which he relates to the company. Any acceptable portrait of Chaucer's Nun's Priest must of necessity derive primarily from the personal interplay during the Canterbury pilgrimage, The Nun's Priest, through the power of rhetoric and his superior intellect, dispenses subtle and didactic criticism which all too often eludes the understanding of the remaining pilgrims in the journey. The high comedy for us, the readers, and for Chaucer the poet, lies, of course, in the Host's missing the subtler points of the tale and holding up to ridicule the meek little priest who has superbly defended him. The Nun's Priest's prowess therefore is intellectual prudence. Most recent criticism has presented the Nun's Priest to us as a brawny and vigorous man with stature and muscles which justify his serving for the duration of the pilgrimage as one of three bodyguards for the prioress and the second nun. This view is based, first on an acceptance as direct description of the Host's extreme comments in the Nun's Priest's epilogue concerning the physical prowess of the Priest; which show that contemporary travel was particularly dangerous for women, even nuns- the assumption beingthat the prioress and the second nun would therefore need husky bodyguards' protection. While the documents concerned can be of great interest, what is of paramount importance in our interpretation of the Nun's Priest is fidelity to the text. The information recorded in the tale could not dictate a brawny physique for the Nun's Priest. Where but one brief explicit statement is available and that one to the effect that this pilgrim is “swete” and “goodly”- considerable differences of opinion concerning the Nun's Priest is at least permissible. Through a re-examination of the pertinent passages in the text, we will be able to maintain that the Nun's Priest is most convincingly visualised as an individual who is scrawny, humble and timid, while simultaneously highly intelligent, well educated, shrewd, and witty. As an important part of this portrait, I will consider the host's remarks in the Nun's Priest's epilogue as being broadly ironic, and Harry Bailey will assume a larger role in the dramatic performance than he has hitherto been granted by commentators. Noone, so far as I can find, has previously called attention to the important and easily acceptable function of the Nun's Priest's epilogue when it is read as broad irony on the part of Harry Bailey. Such an interpretation of the End-link serves as the foundation for my argument; the argument that the nun's priest, while being scrawny, humble and timid is simultaneously a man of well-pruned intellect. Why would the host, who has prudently retreated before the miller's impressive strength and the shipman's evident hardihood, feel free to speak rudely and contemptuously to a large and muscular Nun's Priest? The supposition of a patronising attitude on the part of the henpecked host towards a man who is under the supervision of a woman, the prioress, is simply not adequate explanation for the extreme rudeness and contempt of Harry's remarks to the Nun's Priest, if the latter in conceived of as possessing strength sufficient to make harry fearful of physical violence. In addition, the Nun's Priest complies with Harry Bailey's imperatives and Harry Bailey's command is the Nun's Priest's call to obedience. If we consider the host's reception from the other pilgrims, up until the time that he calls upon the Nun's Priest for the story, we will discover that he has fared rather badly on the pilgrimage. After his success in the arising from the knight's tale, he was successfully challenged by the miller, somewhat annoyed by the reeve’s sermonizing and shortly thereafter threatened by the cook, and then his satisfaction with the man of law's performance was quickly dampened by the shipman's revolt against his authority. In the process of the tales, he is also compelled to recollect his domestic woes and the relationship with his wife. In the succeeding instance, he was offered no relief by the monk, whose tragedies he found exceedingly boring. Finally, when the monk insults the host by haughtily refusing to relate happier material, Harry impolitely 15 turns upon the nun's Priest with a demand that this cleric “Telle us swich thyng as may oure hertes glade.” We must also note that in the course of the first three fragments, Harry plays an important role in connection with every pilgrim's recital. The point is that through these three successive fragments the host's reactions are a vital part of the drama surrounding the various pilgrims’ performances. We, therefore, may not be far wide of the mark if, in trying to derive an acceptable portrait of the Nun's Priest we examine that pilgrim and his tale as they reflect against and fit with the host's recent behaviour. Particularly important here is the host's behaviour before and reaction after the immediately preceding performance, that of the monk. The following view is deduced as a defensible statement concerning the character of the Nun's Priest and the function of his tale in their dramatic context. The host is the central figure in the personal interchanges surrounding the monk's and the nun's Priest's performances. He addresses the physically impressive monk with a lengthy sexual joke; the monk, by means of his dull tragedies then rebuffs the host for the latter's disrespectful and vulgar jocularity towards him. The host therefore gladly seconds the knight's interruption of the monk's series of tragedies, but again left with injured feelings when the monk refuses to comply with his demand for a merry tale on hunting. As a consequence, the host quickly turns upon the feeble and timid Nun's Priest as a cleric upon whom he can safely vent the displeasure which the monk has caused him. The Nun's Priest meekly accepts the host's brusque order for a merry tale and then with many snide and tongue-in-cheek comments brilliantly carries them out. In the tale he even subtly challenges the host's attacker and satirises both the manner and the matter of the monk's recital. Though the host may not realise that he has thus acquired a defender, brilliant though physically weak, the joy of his tale dissipates most of Harry's displeasure, which arose most recently from his treatment by the monk. Then in the epilogue which follows the Nun's Priest's Tale, The host completely regains his good spirits, for in the epilogue he is able to use successfully, in a broadly ironic manner, something of the same sexual joke to which the monk earlier took exception. But what is most interesting is that the host misses the subtler points of the priest's tale and holds him up to ridicule after he has superbly defended the host. The meekness of the Nun's Priest is best evident when he willingly submits to the hosts demand for a merry tale. The host first turns to the monk and unsuccessfully commands him to recount a merry tale. The Nun's Priest, by readily complying with the host's demand, maybe saying, in effect, “even though the monk would not do as you told him, I will.” The Nun's Priest is running no risk of incurring the host's wrath; and the narrator calling him “swete” and “goodly” serves to emphasize the accommodating priest who has just accepted Harry's orders. Though the Nun's Priest may be weak in body and fawning in manner, there is nothing wrong with his intellect and education. In compliance with the Host's request, he relates what is in many ways the outstanding story in the whole collection. And in so doing, he manages to include two clear implications which reveal his own point of view and which can also be taken as a defence of the host. In the first place the Nun's Priest presents a story in which a husband is right and the wife is wrong, in the interpretation of Chauntecleer's dream. Further, though the ostensible moral of the story is that one should not be so careless as to trust in flattery, the Nun's priest slyly places greater emphasis upon another point (3256 – 3266). These antifeminist aspects of the tale mirror the Nun's Priest's way of hinting his dissatisfaction at being under the petticoat rule of the prioress. But they also serve another important function: They are the Nun's Priest's effort to comfort the host, who at home must cope with a dictatorial wife. Further, they furnish a direct answer, a counterpoise, to the theme of the prose tale told earlier by the pilgrim Chaucer, wherein Melibeous was aided by his wife's council. This is a very clever Nun's Priest who can address multiplicity of issues within a single account. The Character of the Nun’s Priest: Conclusion The Nun's priest therefore is a man of formidable stature, not because of his physiognomy but because of a pruned, and polished intellect as wel as sharpness of wit which possesses the ability to humorously and incisively penetrate complex moral issues beneath the surface of superficialities. 16 Additional Notes and Points -There are two theological positions on the concept of predestination, one of which stands as a counterpoise to the other. -St. Augustine, Bishop Bradwardine and Boethius explain the concept as follows; accordingly, predestination is the action by which God is held to have immutably determined all events by an eternal decree or purpose. By this definition God's action foreordains what comes to pass. By this definition of predestination, the whole point of free will is nullified. -The second definition of predestination stands as a counter-poise to the former: accordingly, God, because of that which he foreknew, he also did to predestination. By this definition, man is afforded free will. -Chaucer addresses these two interpretations within this tale, which are a counterpoise to each other. Predestination in the Nun's Priest's Tale -Chaucer, in the Nun's Priest's tale examines the epistemological stance on the subject of predestination and the ensuing debate among scholars and theologians, by entertaining the differing interpretations secured on the tenets of Saint Paul and Saint Peter. -Chaucer addresses two theological views on the concept of predestination and one stands as a counterpoise to the other. -Firstly, he agitates the view held by St, Augustine, Boethius and Bishop Bradwardyn, who unilaterally agree that intrinsic to the full meaning of predestination is the action by which God is held to have immutable determined all events by an eternal decree or purpose. And this was set in place at the inception of time. -By this definition God's action foreordains whatever comes to pass, nullifying free will. -The nun's priest implies this meaning in his declaration that (3217) “By heigh ymaginacioun [God]forncast,” Russel the fox to dwell three years in the grove. -Secondly, a few lines later, the Nun's Priest re-agitates the subject of predestination and once again based on the tenets of Saint Paul and Saint Peter defines the antinomy of the first interpretation as follows: immediate to the meaning of predestination is that God, because of his sovereign foreknowledge also predestined that which will subsequently ensue. In other words for those whom god foreknew, he also predestined. -This definition makes free will admissible. -The Nun's Priest intimates this meaning in his admission in that “what...God forwoot moot needes bee.” -Inherent in these two affirmations are contradictory homilies, equalised and held in unresolved opposition. -This dichotomy, compelled by contradiction, is further amplified through Chaucer's discourse on the subjects of dreams, fortune, etc. Misogyny -The contrary position of misogyny is phylogeny. -In the medieval context, phylogeny also meant that women are the ennoblers of men and can transport them to transcendent heights. Chauntecleer -Firstly, he is portrayed through his physical description -He is used as a tool to mock the heroic epic tradition -Then, he is used as a tool to allegorise matters pertaining to dreams. -Then, he is used as a tool to allegorise the meaning of fortune -Then he is used as a tool to allegorise matters pertaining to predestination. -He is also used as an excuse or a way of escape for the nun's priest when he cannot resolve dichotomous arguments. 17 -Within the ostensible outer-frame of the beast fable genre, Chaucer incorporates a variety of other genres and issues. Chaucer not only is able to convey a variety of morals, sometimes contradictory, but also expose the exclusive nature, biases, and inadequacies of the beast fable genre. -In a beast fable, animals stand in some kind of exemplary relationship to humans. Fable morals are traditionally concerned with practical homely wisdom; how things are, as opposed to how things ought to be, that the foolish are deceived by flattery just as cocks are carried off by foxes. There is, however, abundant room for exploring the incongruity between animals and me and Chaucer carries this to unprecedented lengths. He is keenly aware that while the point of a fable may be outside morality; and his treatment of the story calls attention to all the points that would be outrageously immoral in the human world but are mere facts of life in the barnyard, as for instance, Chauntecleer's seven hens are his “sustres” and “paramours.” Such an abundance of concubines transgresses all taboos on incest, fornication and polygamy. But the effect is more to mock men's pretentions that to show human promiscuity in animals. At the same time, Chauntecleer is emphatically not confined to any existence as mere cock: He is endowed with a complex matrimonial relationship, extensive book-learning, the ability to talk and a psychology as highly developed as any of Chaucer's human characters. Dreams Medievalists were inclined to categorize dreams, and every type of dream was classified under these categories. The nine dreams either described or mentioned in The Nun’s Priest’s Tale fit into one of these categories or include elements from the other categories. The categories are; 1. Somnium = symbolically enjoins beforehand what is to ensue in the future. 2. Insomnium = does not foretell the future in a symbolic way; instead; it recounts the dreamer’s current preoccupations in life and can be caused by mental distress or physical conditions forced by overworking or overeating. 3. Visio = prophesises the future in a dream exactly as it will happen. 4. Oraculum = foretells the future through a figure in the dream who will describe the dream and will advise the dreamer how to avoid it. 5. Visium = does not foretell a dream; instead; when the sleeper is half awake and half asleep, they see shapes around them – nightmares fall into this category. Parelellisms Parallelism simply means balancing ideas with ideas. There are four types: 1. Grammatical = where all parts of speech are balanced with parts of speech within a given sentence; E.g. “What the newspapers say and what the media say are false.” can be economised to “What the newspapers and media say are false.”. 2. Synonymous = (this is not repetition) when you repeat the same idea using different words; E.g. “Sons of myself…” Or “One’s self I sing…” o Or “A single separate person…” 3. Antithetical = when two opposite ideas are juxtaposed within a line or lines; E.g. “Ham’s intense desire is to locate the centre./The centre, however, is displaced to the periphery.” – ‘centre’ and ‘periphery’ are antithetical, forcing antithetical parallelism. 4. Synthetic = when two ideas will merge to affect the dialectics of change. When there is a dialectical relationship between two contrary principles, it will affect the dialectics of change, at which point the two ideas will synthesise or merge to generate the higher truth or a new idea.