Grammatical Noriegas - University College London

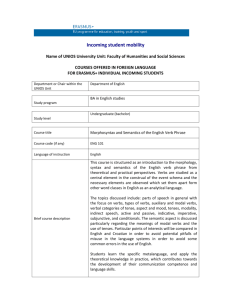

advertisement

That vexed problem of choice

reflections on experimental design and statistics

with corpora

ICAME 33

Leuven 30 May-3 June 2012

Sean Wallis, Jill Bowie and Bas Aarts

Survey of English Usage

University College London

{s.wallis, j.bowie, b.aarts}@ucl.ac.uk

Outline

• Introduction

• Definitions

• Refining baselines and the ratio principle

• Surveying ‘absolute’ and ‘relative’ variation

• Potential sources of interaction

• Employing alternation analysis

• Objections

• Conclusions

Introduction

• Research questions are really about choice

– If speakers had no choice about the words or

constructions they used, language would be invariant!

• Lab experiments

– Press button A or button B

• Corpus

– Speakers may choose construction A or B

• But they can only actually chose one, A, at each point

• We have to infer the other type, B,

counterfactually

• Identifying alternates is often non-trivial

Mutual substitution

• Mutual substitution A B

– Given a corpus, identify all events of Type A that

alternate with events of Type B, such that A is

mutually replaceable by B, without altering the

meaning of the text.

• Replacement

– B replaces A if B increases, and vice-versa

• p (A)+p (B)+... = 1

• Freedom to vary

• p (X) [0, 1]

– Ideal: eliminate invariant Type C terms

Mutual substitution

• Mutual substitution A B

– Pronoun who/whom

• A = whom

• B = who

Mutual substitution

• Mutual substitution A B

– Pronoun who/whom

• A = whom

• B = who (objective)

– But whom is limited to objective case

• C = who (subjective)

• We therefore limit alternation to Objects

– If whom is used ‘incorrectly’ as a Subject, it has an

additional constraint (social disfavour)

True rate of alternation

• True rate of alternation

– If A B

F (A)

• p (A | {A, B}) =

F (A)+F (B)

True rate of alternation

• True rate of alternation

– If A B

F (A)

• p (A | {A, B}) =

F (A)+F (B)

• Proportion (fraction) of all cases that are Type A

– we use p (A) as a shorthand for p (A | {A, B}) if the

baseline {A, B} is stated

True rate of alternation

• True rate of alternation

– If A B

F (A)

• p (A | {A, B}) =

F (A)+F (B)

• Proportion (fraction) of all cases that are Type A

– we use p (A) as a shorthand for p (A | {A, B}) if the

baseline {A, B} is stated

• Contingency tables

IV

DV A

Total

B

condition 1 f1(A) f1(B) f1(A)+f1(B)

condition 2 f2(A) f2(B) f2(A)+f2(B)

Total

F (A) F (B) F (A)+F (B)

probability

p1(A)

p2(A)

p (A)

True rate of alternation

• Shall/will alternation over time in DCPSE

1

p

baseline = {shall, will}

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

1955

1960

1965

1970

(Aarts et al., forthcoming)

1975

1980

1985

1990

1995

True rate of alternation

• Shall/(will+’ll) alternation over time in DCPSE

1

baseline = {shall, will, ’ll}

p

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

1955

1960

1965

1970

(Aarts et al., forthcoming)

1975

1980

1985

1990

1995

True rate of alternation

• Logistic ‘S’ curve assumes freedom to vary

– p (X) [0, 1]

1

p

t

0

True rate of alternation

• Logistic ‘S’ curve assumes freedom to vary

– p (X) [0, 1]

1

p

shall/(will+’ll)

shall/’ll

t

0

– as do Wilson confidence intervals

Refining baselines

• Over-general baselines

– conflate opportunity and use

– ‘normalisation’ per million words

• implies that every word other than A is Type B!

• is this plausible?

B A

• ‘Art’ of experimental design

– refine baseline by narrowing dataset

• reduce and eliminate non-alternating Type C cases

• optionally: subdivide where different constraints apply

– different baselines test different hypotheses

• cf. shall / will / ’ll

Refining baselines

• Tensed VPs per million words, DCPSE

Total:

constant over

time

140,000

120,000

Diachronic

variation:

within text

categories

100,000

80,000

60,000

(Bowie et al., forthcoming)

Total

prepared sp

assort spont

legal x-exam

parliament

commentary

b interviews

b discussions

telephone

informal f-to-f

formal f-to-f

20,000

0

Synchronic

variation:

between text

categories

LLC

ICE-GB

40,000

The ratio principle

• Simple algebra

– any sequence of ratios can be reduced to the ratio

of the first and last term:

F (modal)

F (tVP)

F (modal)

F (tVP)

F (word)

F (word)

The ratio principle

• Simple algebra

– any sequence of ratios can be reduced to the ratio

of the first and last term:

F (modal)

F (tVP)

F (modal)

F (tVP)

F (word)

F (word)

– we saw that the ratio tVP:word varies

synchronically and diachronically in DCPSE

• we can eliminate this variation by simply focusing on

modal:tVP

• use tensed VPs as baseline for modals

The ratio principle

• Simple algebra

– any sequence of ratios can be reduced to the ratio

of the first and last term:

F (modal)

F (tVP)

F (modal)

F (tVP)

F (word)

F (word)

– we saw that the ratio tVP:word varies

synchronically and diachronically in DCPSE

• we can eliminate this variation by simply focusing on

modal:tVP

• use tensed VPs as baseline for modals

– this baseline is not a strict alternation set

• we have not eliminated all Type C terms

‘Absolute’ and ‘relative’ variation

• Changes in core modals over time in DCPSE

p (modal | tVP)

p (modal | modal tVP)

0.30

0.04

0.25

0.03

0.20

0.15

0.02

0.10

0.01

0.05

0.00

0.00

can

could may might must shall should will would

(Bowie et al., forthcoming)

Left axis:

absolute change

as a proportion

of tensed VPs

Right axis:

relative change

as a proportion

of set of modals

Employing alternation analysis

• Simple grammatical interaction

– Independent and dependent variables are

grammatical

• mutual substitution concerns the dependent variable

Employing alternation analysis

• Simple grammatical interaction

– Independent and dependent variables are

grammatical

• mutual substitution concerns the dependent variable

– Numerous examples in Nelson et al. 2002

• e.g. clause table: mood transitivity

IV

DV

exclamative

interrogative

Total

montr

ditr

CL(montr, exclam) CL(ditr, exclam)

CL(montr, inter)

CL(ditr, inter)

…

…

CL(montr)

CL(ditr)

Total

CL(exclam)

CL(inter)

…

CL

• not alternation, but survey: could be refined

Employing alternation analysis

• Repeating choices: to add or not to add

– e.g. repeated decisions to add an attributive AJP to specify

a NP head: the tall white ship

• A = add AJP

• B = don’t add AJP (and stop)

Employing alternation analysis

• Repeating choices: to add or not to add

– e.g. repeated decisions to add an attributive AJP to specify

a NP head: the tall white ship

• A = add AJP

• B = don’t add AJP (and stop)

– Sequential analysis: examine p (A | {A, B}) at each step

0.25

p

Conclusion:

decision to add

an AJP becomes

successively

more difficult

0.20

0.15

0.10

0.05

0.00

0

1

(Wallis, forthcoming)

2

3

4

Employing alternation analysis

• Grammatically diverse alternates

– Biber and Gray (forthcoming) investigate evidence for

increasing nominalisation

• A = nouns that have been derived from verb forms

– This paper reports an analysis of Tucker’s central prediction

system model and an empirical comparison of it with two

competing models. [1965, Acad-NS]

• B = verbs that could be nominalised

Employing alternation analysis

• Grammatically diverse alternates

– Biber and Gray (forthcoming) investigate evidence for

increasing nominalisation

• A = nouns that have been derived from verb forms

– This paper reports an analysis of Tucker’s central prediction

system model and an empirical comparison of it with two

competing models. [1965, Acad-NS]

• B = verbs that could be nominalised

– Could just use clauses as baseline

• But this is little better than words

– Better option is to enumerate types

• analysis

• prediction

• comparison

• analyse

• predict

• compare

Employing alternation analysis

• Grammatically diverse alternates

– Biber and Gray (forthcoming) investigate evidence for

increasing nominalisation

• A = nouns that have been derived from verb forms

– This paper reports an analysis of Tucker’s central prediction

system model and an empirical comparison of it with two

competing models. [1965, Acad-NS]

• B = verbs that could be nominalised

– Could just use clauses as baseline

– Better option is to enumerate types

• analysis

• prediction

• comparison

• analyse

• predict

• compare

– Examine cases: is alternation possible?

Objections

• If this is such a good idea, why isn’t

everybody doing it?

• Three main objections are made:

alternates are not reliably identifiable

baselines are arbitrarily chosen by the

researcher

different constraints apply to different terms

(no such thing as free variation)

Alternates are not reliably identifiable?

• Identifying alternates can be difficult

– phrasal vs. Latinate verbs

Alternates are not reliably identifiable?

• Identifying alternates can be difficult

– phrasal vs. Latinate verbs

• Strategies:

enumerate cases from bottom, up

• find Type B cases for each Type A

Alternates are not reliably identifiable?

• Identifying alternates can be difficult

– phrasal vs. Latinate verbs

• Strategies:

enumerate cases from bottom, up

• find Type B cases for each Type A

put up tolerate

?position

build, make

display, project

sell

propose

increase

accommodate

finance

4

3

3

2

2

2

1

1

1

put up with it [S1A-037 #1]

put your feet up [S1A-032 #21]

shacks put up without any planning [S2B-022 #118]

put up two… trees [on the screen] [S1B-002 #157]

put the plant up for sale [W2C-015 #8]

put [a motion] up [S1B-077 #127]

put up the poll tax [W2C-009 #3]

we could put up the children [S1A-073 #197]

put up the money [W2F-007 #36]

Alternates are not reliably identifiable?

• Strategies:

enumerate cases from bottom, up

• find Type B cases for each Type A

Alternates are not reliably identifiable?

• Strategies:

enumerate cases from bottom, up

• find Type B cases for each Type A

refine baseline from top, down

• start with verbs, eliminate non-alternating Type Cs

– Copular verbs

– Clitics

– Stative verbs

• are dynamic verbs the upper bound for alternation

with phrasal verbs?

Alternates are not reliably identifiable?

• Strategies:

enumerate cases from bottom, up

• find Type B cases for each Type A

refine baseline from top, down

• start with verbs, eliminate non-alternating Type Cs

– Copular verbs

– Clitics

– Stative verbs

• are dynamic verbs the upper bound for alternation

with phrasal verbs?

– combine strategies:

• identify stative verbs lexically

• a few verbs are stative and dynamic

– check in situ

Baselines are arbitrary?

• Is there such an ‘objective’ baseline?

– No, but optimum baselines identify where

speakers have a real choice: Type A vs. Type B

• Baselines are a control

– Experimental hypothesis:

• the ratio of Type A to the baseline is constant over

values of independent variable

– Baseline cited as part of experimental reporting

• Indeed we can experiment with baselines

– e.g. does the present perfect correlate

more with past-referring or

present-referring VPs?

Comparing baselines

• Does the present perfect correlate more with

past-referring or present-referring VPs?

Comparing baselines

• Does the present perfect correlate more with

past-referring or present-referring VPs?

present

present perf

present non-perf

Total

LLC

ICE-GB

2,696

2,488

5,184

33,131

32,114

65,245

35,827

34,602

70,429

present perf

other TPM VPs

Total

2,696

2,488

5,184

18,201

14,293

32,494

20,897

16,781

37,678

Total

past

LLC

ICE-GB

Total

(Bowie et al., forthcoming)

Comparing baselines

• Does the present perfect correlate more with

past-referring or present-referring VPs?

present

present perf

present non-perf

Total

LLC

ICE-GB

2,696

2,488

5,184

33,131

32,114

65,245

35,827

34,602

70,429

present perf

other TPM VPs

Total

2,696

2,488

5,184

18,201

14,293

32,494

20,897

16,781

37,678

Total

past

LLC

ICE-GB

Total

– Present perfect correlates more with

present-referring VPs

(Bowie et al., forthcoming)

d% = -4.455.13%

f’ = 0.0227

c2 = 2.68ns

d% = +14.925.47%

f’ = 0.0694

c2 = 25.06s

Different constraints apply in each case?

• Speakers choices are influenced by multiple

pressures

– to talk about a single ‘choice’ is misleading

– there is no such thing as free variation

• We are not attempting to infer “the reason” for

a particular speaker decision

– we are attempting to identify statistically sound

• patterns

• correlations

• trends

– across many speakers

Different constraints apply in each case?

• Does one or more of these multiple constraints

represent a systematic bias on the true rate?

Yes = try to identify it experimentally

No = ‘noise’

• Can focus on subset of cases to restrict

different influences

– e.g. limit shall / will by modal semantics

• This objection is misplaced:

– freedom to vary

= grammatical and semantic possibility (potential)

= not that choices are free from influence

A competitive ecology?

• Not everything is a binary choice

– but the same principles apply

100%

100%

p

p

Meanings of THINK

Complementation patterns of HOPE

hoping that / Ø

80%

80%

‘cogitate’

60%

60%

40%

40%

hoping to

‘intend’

20%

20%

quotative

hoping for

interpretive

0%

0%

1920s

1960s

(Levin, forthcoming)

2000s

1920s

1960s

2000s

Conclusions

• Researchers need to pay attention to questions of

choice and baselines

– This does not mean that an observed change is due to a

single source

• Minimum condition: baseline is a control

– statistics evaluate difference from this control

• is it a good control?

• Alternation studies: baseline is opportunity for

making choice under investigation

• Word-based baselines should only really be used for

comparison with other studies

– we should not make statements about choice

unless we investigate that question

Conclusions

• ‘Alternation’ can be interpreted

– strictly

• all Type As and Type Bs identified and cases checked

– generously

• small number of Type Cs permitted

– Alternation is semantically bounded but

grammatical analysis helps identify cases!

• We may try different experimental designs,

modifying baselines and subsets

– many more novel experiments are possible

• experimental assumptions

should always be clearly reported

References

ACLW: Aarts, B., J. Close, G. Leech and S.A. Wallis (eds.) (forthcoming).

The Verb Phrase in English: Investigating recent language change with

corpora. Cambridge: CUP.

Preview at www.ucl.ac.uk/english-usage/projects/verb-phrase/book.

•

Aarts, B., J. Close and S.A. Wallis. forthcoming. Choices over time:

methodological issues in investigating current change. ACLW Chapter 2.

•

Biber, D. and B. Gray. forthcoming. Nominalizing the verb phrase in academic

science writing. ACLW Chapter 5.

•

Bowie, J., S.A. Wallis and B. Aarts, forthcoming. The perfect in spoken English.

ACLW Chapter 13.

•

Levin, M., forthcoming. The progressive verb in modern American English. ACLW

Chapter 8.

•

Nelson, G., S.A. Wallis and B. Aarts. 2002. Exploring Natural Language.

Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

•

Wallis, S.A. forthcoming. Capturing linguistic interaction in a grammar:

a method for empirically evaluating the grammar of a parsed corpus.

Statistical postscript

• Type Cs make statistical tests less sensitive

– What happens to confidence intervals as we add

to F (A)+F (B) = 100 alternating cases?

0.25

eN/100

F (A)

0.2

95

80

60

0.15

Including Type Cs

makes statistical

tests conservative

40

0.1

20

0.05

5

0

100

1,000

10,000

Tests assume

freedom to vary

(F (A)+F (B) = N )

N