Title of Presentation - Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims Bar

advertisement

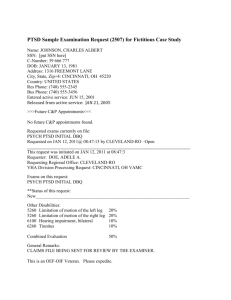

Robert G. Moering, Psy.D. Licensed Psychologist James A. Haley VAMC MISSION STATEMENT The VHA: "Honor America's Veterans by providing exceptional health care that improves their health and well-being" No official mission statement for C&P exams "To provide evidence-based mental health assessments of veterans claiming service-connected disabilities in order to help the Veterans Benefits Administration make accurate benefit determinations.“ Clearly, these missions are not the same Forensic refers to professional practice by any psychologist who applies the scientific, technical, or specialized knowledge of psychology to the law to assist in addressing legal, contractual, or administrative matters. Clinical refers to professional practice by any psychologist who applies the scientific, technical, or specialized knowledge of psychology to address treatment issues. Forensic: Evidenced Based and Multi-Method Review of Records Collateral Information usually obtained Psychological testing typically administered Usually One visit Clinical: Self Reports May or may not review records May or may not obtain collateral information Psychological testing typically not done Multiple visits Are C&P Exams Forensic Exams? Are C&P exams intended to help answer legal or clinical questions?" C&P exams help answer legal (not clinical) Qs Medical Opinions requested come from U.S. statutes, regulations, and case law. I.e., Is a veteran's stressor is related to "the veteran’s fear of hostile military or terrorist activity." This question did not arise because of clinical concerns but because of a change in the Federal Regulations governing these exams. (1) Forensic Guidelines Professional Organizational Guidelines: American Academy of Psychiatry and Law's "Practice Guideline for the Forensic Evaluation of Psychiatric Disability” American Psychological Association’s “Specialty Guidelines for Forensic Psychology,” The Practice Guideline (2) highlights some of the differences between clinical and forensic evaluations Opinions are impartial, fair, independent Weigh all data, unbiased, avoid partisan presentation of data Why not use the Treatment Notes? Providing forensic and therapeutic services impairs objectivity Treatment providers do not access c-file records Treatment providers rely entirely on veteran’s self-reported history e.g., Veteran seen for TBI, PTSD secondary to combat in Iraq; military personnel records and service medical records clearly show he never deployed from MacDill AFB “Pt. states he killed over 600 VC as an infantryman and was awarded a Bronze Star w/V for his heroism.” Reality? Treatment Notes : Don’t Believe Everything You Read Veteran 100% SC Seeking A/A Claims wheelchair bound, Tx notes indicate same Claims unable to transfer on his own, Tx notes indicate same Claims unable to move his legs, Tx notes indicate same C&P Examiners are not mind readers The 2507 request is paramount to getting it right “Please opine if the [insert condition here] is related to his [insert condition here].” “PTSD due to fear of military or hostile terrorist acts” versus “PTSD or any acquired psychiatric disorder” Identify specific records in c-file you want the examiner to comment on don’t put “see c-file” or “note is tagged with sticky note” Specify: “Dr. X note dated 3/3/10” CPRS note dated 1/1/11” What Did We Review? Remand cases require the examiner to thoroughly review the c-file and BVA Remand Imperative to note the review of the c-file Mental Health Exams require C-File review Initial and Review CPRS Records (Local and Remote) Example: CPRS records including remote data from Orlando and Atlanta, service medical records, military personnel records, veteran’s lay statements, BVA Remand, 6 volumes of c-file records, collateral statements from XX and XX, relevant research (see references below), psychological test results Structured Interviews Current research clearly shows the use of structured interviews are significantly and statistically superior in assessing for PTSD and other disorders versus an unstructured or semi-structured interview. (3-9) Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale Developed by the VAs National Center for PTSD Recommended in “Best Practice Manual” (2) Easy to use - CAPS interview form, manual, and training videos are all available at no charge: (http://vaww.ptsd.va.gov/Assessment.asp). Assess symptom frequency and severity Determine how symptoms interfere with functioning (important for rating purposes) More reliable and valid diagnostic decisions CAPS Nine scoring methods, or rules Each of the rules differs with regard to their sensitivity, specificity, and the extent to which they can be considered lenient or strict with regard to the ultimate diagnostic decision. The "F1/I2" scoring rule is the most lenient of the nine possible scoring rules. (10) This scoring rule gives the veteran the greatest degree of benefit of doubt. Other Interview Questionnaires Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) Cyclothymic Disorder Agoraphobia Without History of Panic Disorder Social Phobia / Specific Phobia Generalized Anxiety Disorder Somatization Disorder / Undifferentiated Somatoform Hypochondriasis / Body Dysmorphic Disorder Anorexia Nervosa / Bulimia Nervosa Schedule for Affective Disorders & Schizophrenia (SADS) (semi-structured) MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.) (semi-structured) VA Developed Measures of Combat Combat Exposure Scale (CES) 7 item assessing combat experiences 0-8 Light 9-16 Light to Moderate 17-24 Moderate 25-32 Moderate to Heavy 33–41 Heavy Example Items: Were you ever under enemy fire? How often did you fire round at the enemy? How often were you in danger of being injured or killed (i.e., pined down, overrun, ambushed, near miss, etc.)? Mississippi Combat Stress Scale (MISS) 35 items assessing PTSD-related symptoms Self-rating scale from 1-5 Example Items: If something happens that reminds me of the military, I become very distressed and upset. Before I entered the military, I had more close friends than I have now. I am able to get emotionally close to others. Unexpected noises make me jump. I feel comfortable when I am in a crowd. Problems with CES and MISS Studies have shown that face-valid measures such as the Mississippi Scales are ineffective in distinguishing between individuals with genuine PTSD and persons who simulate PTSD (11) MST Most challenging type of examination Victims are reluctant to disclose More often than not the assault not reported MST cases require special care to provide the most comprehensive examination possible. The Basic MST Opinion Request “Please review the veteran’s entire claims file and medical records and provide an opinion as to whether it is at least as likely as not that the veteran’s records support the occurrence of a military personal trauma/sexual assault.” Note: Personal assaults may be classified as a nonsexual trauma (e.g., physical assault, domestic battery, robbery, and etc) or sexual trauma (e.g., rape, stalking, sexual harassment). Court’s Influence Wood v. Derwinski (1991) - VA is not bound to accept a veteran’s uncorroborated account of what happened in service, regardless of whether a social worker or psychiatrist believes her or him. Moreau v. Brown (1996) and Dizoglio v. Brown (1996) "credible supporting evidence" = Vet’s testimony, by itself, can’t establish the noncombat stressor. Doran v. Brown (1994) - "the absence of corroboration in the service records, when there is nothing in the available records that is inconsistent with other evidence, does not relieve the BVA of its obligations to assess the credibility and probative value of the other evidence.” Patton v. West (1999) - Special development required for MST-related cases. Court distinguished the case from Moreau and Cohen, which were not personal assault cases. At the time - Manual stated veteran’s behavioral changes at and around the time of the alleged incident might require interpretation by a clinician. Courts determine there must be credible evidence to support the veteran’s assertion that the stressful event occurred. Court established the development of personal assault cases is different because part of the development of personal assault claims included allowing “interpretation of behavior changes by a clinician and interpretation in relation to a medical diagnosis.” Clinical interpretations of a veteran’s behavior is allowed so an opinion by a M/H professional could be used to corroborate an in-service stressor. The Court also noted the importance of discussing the credibility of all evidence, including lay statements, when providing an adequate statement of reasons and bases Examiner outlined extensive reasoning why a condition was not related to service including references to service medical records, CPRS records, c-file records, etc… Remanded back because veteran’s lay statements not discussed in rationale According to 38 CFR 3.304(f)(4), in cases of a noncombat personal assaults, corroborating evidence may come from other sources besides the veteran’s service records. YR v. West (1998) - Highlights importance of addressing credible corroborating evidence = Analyzing submitted alternative sources of evidence is very important in MST cases. Cohen v. Brown (1997) - “[a]n opinion by a mental health professional based on a post service examination of the veteran cannot be used to establish the occurrence of the stressor.” The Federal Circuit concluded that the Federal Regulations allows veterans claiming PTSD from an in-service personal assault to submit evidence other than in-service medical records to corroborate the occurrence of a stressor, to include medical opinion evidence. Menegassi v. Shinseki (2011), U.S. Court of Appeals upheld the BVA denial of S/C for MST Veteran DX PTSD but BVA said no evidence in C-file The Veterans Court stated that an opinion by a MH professional based on a post-service exam cannot be used to establish the occurrence of a stressor. Veteran’s lay statement is insufficient evidence Medical opinion based on a post-service examination is insufficient evidence Evidence must be obtained from the veteran’s C-file records (i.e., service medical records, military personnel records, police reports, witness statements, lay statements, or Court Martial records). So, What Does This Mean to Me? Read the service medical records Read the military personnel records Read ALL CPRS records Read all lay statements Inform the veteran of alternate evidence Comprehensive evaluation Re-Read all the above Consult with colleagues and physicians Comment on EVERYTHING, Rational Reasoning If I don’t have it, ask for it! Case Example Female veteran was claiming PTSD secondary to physical and sexual abuse perpetrated by her husband. The C-file contained multiple police records and court documents indicating she claimed selfdefense bc he was physically assaulting her Convicted of 2nd degree murder by a jury of her peers who rejected the self-defense claim. SMR showed MH only after she was arrested and on the advice of her attorney Cont. Service personnel records, police reports, court records, and 15 years of prison records, there was significant doubt regarding the veteran’s claim of physical and sexual assault. Parole Release request indicated a 1st trial ended in mistrial because jury could not agree on verdict At 2nd trial the veteran did not have several key witnesses (PCS, unable to locate, etc) Requested 1st trial records = Multiple documents supporting veteran’s claim Case Example Veteran said was raped while a patient at XYZ Hospital We verified in her records she was at XYZ Hospital “We have conceded she was raped because she was where she said she was.” “Markers” Markers = clues within the records which show a change in behavior, health, or other functioning that, when combined lead an examiner to conclude some event in the veteran’s life around the time of the noted changes were responsible for those changes Example Markers visits to a medical or counseling clinic or dispensary without a specific diagnosis or specific ailment use of pregnancy tests or tests for sexuallytransmitted diseases around the time of the incident sudden requests that the veteran's military occupational series or duty assignment be changed without other justification changes in performance and performance evaluations increased or decreased use of prescription medications increased use of over-the-counter medications evidence of substance abuse, such as alcohol or drugs increased disregard for military or civilian authority obsessive behavior such as overeating or undereating increased interest in tests for HIV or sexually transmitted diseases unexplained economic or social behavior changes treatment for physical injuries around the time of the claimed trauma, but not reported as a result of the trauma, and/or the breakup of a primary relationship. Finding the Markers Service medical records requests for specific tests (e.g., venereal disease, pregnancy testing, or HIV) evidence of increased use of alcohol (e.g., referred to or attended substance abuse counseling) “Seen in Mental Health.” “Seen in ER for…” Lack of Mental Health Records MH treatment avoided because of stigma Look for hidden evidence For example, a veteran complaining to a primary care provider they were having shortness of breath, chest pains, and sweating might be experiencing symptoms of anxiety known etiology (SOB 20 asthma) < marker Unknown etiology = possible marker Is a “Marker” a “Marker” some conditions may have medical explanations but psychiatric implications. For example, a service member is seen in the medical clinic and diagnosed with “gastritis.” Sxs of gastritis include: Nausea or recurrent upset stomach abdominal pain vomiting indigestion loss of appetite. Symptoms could because gastritis or anxiety. Is a “Marker” a “Marker” One visit for “Gastritis” = less likely Multiple visits for “Gastritis” = more likely One Visit for headaches = less likely Multiple visits for headaches = more likely Headaches in 1975, MST in 1977 = no marker > # of HA starting 1977 = marker Negative “Markers” in SMR No direct reports (e.g., raped, seen by MH) No indirect reports (e.g., headaches) Report of Medical History form = Negative After giving all possible benefit of the doubt and there is nothing to “hang your hat on” = consider the service medical records to be negative for signs of any “Markers” Military Personnel Records Military personnel records may reveal “markers of trauma. Enlisted Performance Report Letters of Counseling/Reprimand UIF Article 15, Page 11, Office Hours, Captain’s Mast Court Martial Enlisted Performance Report Military Personnel Records Cont. Drop in ratings show significant behavioral changes consistent with a Marker Look at overall ratings Not as helpful as EPR Is this “Good” a “Marker” Perhaps not when it’s followed by… Veteran’s Reports Vs. Records Veteran says “argued, fought, never got along with anyone” Performance Records show: “Well liked and respected by peers and supervisors, is the go-to guy in his unit” “She is a very pleasant, outgoing airman who works well with her customers, peers, and supervisors.” “Needs to improve his relationships with both peers and supervisors” “Has been counseled a number of times to leave his personal life at home” Veteran says, “I was always stressed at work and getting into trouble for poor performance and attitude problems.” Records show: “She can be trusted to handle even the most stressful customers with tact, professionalism, and military bearing. “ “He is the number one go-to soldier when things need fixing” “He used to he a reliable sailor, but now…” Disciplinary Actions Article 15, Court Martial, Captain’s Masts, etc., may be “Markers” Prevalence rate of Article 15? DK but common Timing When did the NJP occur 4 NJP before MST and 1 after = not a marker What’s the “crime” Charged with Rape or AWOL “failure to maintain clean room” or “Disrespect” Case Example: Veteran served 4 years First 3 years = 3 Company Grade Article 15s for disrespecting his NCOIC. Last year = 3 Field Grade Article 15s for disrespecting his CO (X1) and AWOL (X2). Existence of NJP is not a Marker given the three disciplinary actions prior to the trauma BUT the increase in disciplinary actions and the reasons for the disciplinary actions indicated the possibility of a trauma. Other Evidence Lay statements from family members Letters from the veteran’s roommate Lay statement from a spouse or child who did not know the veteran at the time of the personal assault is not supporting evidence of the occurrence of a stressor but may support the subsequent diagnosis Letters from clergy at the time of the stressor Letter from off-duty employment at the time Diagnostic Benefits Questionnaires VBA coordinates with VHA and BVA and OGC 81 DBQs DBQs standardize VHA exam reports Enable private physicians to provide sufficient disability assessment information DBQs from private physicians will preclude the need for VA exams in many cases. Problems with the DBQ DBQ lacks the ability to identify either the frequency or the severity of a symptom. The frequency and severity of a symptom make a significant difference in the overall impact on a person’s functioning. Helps examiners and raters doing reviews Improved inter-rater reliability Use specific behavioral anchors Eliminate idiosyncratic threshold determinations. Example: Depressed Mood Frequency: Once or twice a month Once or twice a week Several times a week Daily or almost every day Severity: Slight - e.g., occasionally “sad" or occasionally poor concentration Mild - e.g., often feels somewhat "depressed," mild insomnia Moderate - e.g., few friends, conflicts with peers, flat affect Severe - e.g., suicidal ideations, neglects friends, skips work Extreme - e.g., attempts suicide, stay in bed all day, incoherent CAPS is the “Gold Standard” in assessing PTSD Embed the CAPS into the DBQ E.g., frequency and intensity of each symptom Improves diagnostic reliability Add section for Psychological Test Results The only DBQ template that incorporates this is TBI TBI templates are not done by psychologists Occupational and Social Impairment Directly correlates to mental health rating scale C&P examiner as the “rater” Examiner is the “face” to the C&P process 4. Occupational and social impairment a. Which of the following best summarizes the Veteran's level of occupational and social impairment with regards to all mental diagnoses? (Check only one) [ ] No mental disorder diagnosis [ ] A mental condition has been formally diagnosed, but symptoms are not severe enough either to interfere with occupational and social functioning or to require continuous medication [ ] Occupational and social impairment due to mild or transient symptoms which decrease work efficiency and ability to perform occupational tasks only during periods of significant stress, or; symptoms controlled by medication [ ] Occupational and social impairment with occasional decrease in work efficiency and intermittent periods of inability to perform occupational tasks, although generally functioning satisfactorily, with normal routine behavior, self-care and conversation [ ] Occupational and social impairment with reduced reliability and productivity [ ] Occupational and social impairment with deficiencies in most areas, such as work, school, family relations, judgment, thinking and/or mood [ ] Total occupational and social impairment Etiologies: Not Fully Known Common factors — comorbidity results from risk factors common to both disorders (e.g., genetics) Secondary mental disorder — substance use precipitates mental disorders. Secondary substance use — 'self-medication hypothesis' Bidirectional — presence of either a mental disorder or SUD can contribute to the development of the other in a mutually reinforcing manner over time. (31) The presence of two or more disorders, is common possibly more common than a single diagnosis. The Epidemiological Catchment Area study (lifetime) - ≈ 60 percent of those with at least one disorder qualified for two or more diagnoses, National Comorbidity Survey Replication – ≈45% In the NCS-R (lifetime) - ≈14% qualified for three or more diagnoses NCS-R - ≈ 23% qualified for at least three. Multiple studies have linked the use of alcohol to PTSD (2X as likely) Problem: ↑ alcohol = harder to cope Alcohol use and intoxication ↑ some PTSD symptoms Emotional numbing, detached, irritability, anger, depression, being on guard, sleep disturbance Comorbidity Opinions Separating symptoms: Some symptoms overlap, some don’t If all (almost all) the symptoms overlap, is there a 2nd Dx? Etiology of symptoms: What came first – the symptom or the trauma? Exacerbated symptoms? Alcohol/drug abuse before the trauma? “Dual diagnosis" most commonly refers to the combination of "severe mental illness" (SMI) and a substance-use disorder (SUD). ETOH/drug = adversely influence affective stability, cognition, and behavior Mental disorders place individuals at risk for substance abuse and dependence. Comorbidity = complicate clinical management and is associated with poorer outcomes. According to Regier et al. (1990) Anxiety disorders – overall 15% SUD rate GAD (21%), PTSD (18%), Social Phobia (17%) Mood disorders — Individuals with mood disorders have a lifetime SUD rate of 32 percent Schizophrenia — 47% have had an SUD over their lifetime (30) DSM-IV specifically indicates “(m)alingering should be ruled out in those situations in which financial remuneration, benefit eligibility, and forensic determinations play a role (pg. 467). abundant research literature demonstrating that compensation-seeking veterans exhibit high rates of symptom exaggeration Calhoun, Earnst, Tucker, Kirby, & Beckham, 2000; Dalton, Tom, Rosenblum, Garte, & Aubuchon, 1989; DeViva & Bloem, 2003; Freeman, Powell, & Kimbrell, 2008; Frueh, Gold, & de Arellano, 1997; Frueh, et al., 2003; Smith & Frueh, 1996; Sparr & Pankratz, 1983 Various reasons why a veteran might overreport symptoms. The severity of their illness. Generalized distress Socio-political considerations "Vietnam veterans ... experienced unique pressures and traumas while in a war zone ... and were caught in a period of social transition and stress upon return from the war." Vietnam vets just now 'learning' to respond to years of dormant thoughts and feelings Compensation-seeking status - "really make their case” Psychological Testing? In general, psychological tests are as accurate as medical tests (Meyer, et al., 2001). (27) “Clinicians who rely exclusively on interviews are prone to incomplete understandings" (Meyer, et al., 2001, p. 128). Psych tests (e.g., MMPI-2 & SIRS) = proven to possess highly accurate classification rates Actuarial judgment outperforms clinical judgment (Dawes, Faust, & Meehl, 1989). (29) Cont. MMPI-2 or PAI Miller Forensic Assessment of Symptoms Test (M-FAST) Structured Interview of Reported Symptoms (SIRS/SIRS-2) Morel Emotional Numbing Test for PTSD (MENT) Structured Inventory of Malingered Symptomatology (SIMS) Test of Memory Malingering (TOMM) MMPI-2 Most widely used measure Franklin, et al. (2002) conducted research on MMPI-2 scores of veterans undergoing a C&P exam. Their results suggested "…a majority of veterans with elevated F scale scores are not intentionally overreporting their symptoms, but likely are achieving high elevations due to extreme distress" (32) Graham (2006) describes "attempts to fake bad or malinger." (33) Validity scales have been found to be reliable indicators of exaggeration or feigning when evaluating combat veterans with PTSD (Tolin, et al., 2010). (36) Combat veterans tend to elevate validity scales even when they have genuine PTSD (Franklin, et al., 2002) But, there is a limit to the elevation (Resnick, West, & Payne, 2008). (35) MENT Only measure specifically developed and normed on veteran seeking VA compensation for PTSD. (37) SLEEPY SERIOUS Cont. Minimizing WW-II and Korea veterans have history of minimizing psychiatric symptoms. Often deny problems Culture of the generation “greatest generation” Active Duty military Depends on reason for evaluation All records including remote data should be reviewed. Ability to see consistencies and inconsistencies Military personnel records versus treatment notes Aviation Operation Specialist ≠ Door Gunner Processes flight clearances, check accuracy of flight plans, coordinates flight plans DD Form 214 versus reality Southwest Asia Service Medal ≠ Combat Case Example 6/2011 veteran has TDRL eval Veteran wants to reenlist in USMC Denied all psychiatric symptoms Denied reenlistment 2/2012 veteran has C&P evaluation Endorses every symptom associated with PTSD Denied remission of symptoms since 2005 Awarded 100% S/C Was he misleading the Navy psychiatrist or VA psychologist? Case Example Veteran tells VA psychologist: “perfect childhood” No behavioral issues Denied substance use pre-military Raped while on leave Service medical records Significant childhood behavioral issues (arrested multiple times) Abused marijuana pre-military history of physical abuse Psychiatric/psychological eval = rape fabricated to keep out of trouble Diagnosed Antisocial Personality Disorder Military personnel records 2 Article 15s pre “trauma” Multiple Page 11 entries pre “trauma” Was UA for 17 days, when picked up by MP claimed he was robbed and raped No disciplinary actions in the 6 months between “trauma” and discharge Post Military Incarcerated 4X for armed robbery and assaults in Ohio (17 years total) Incarcerated 2X in Florida for Aggravated Battery with deadly Weapon (4 years total) Heavy alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, heroin Means for Assessing Quality of Life Inventory (QOLI) - measures life satisfaction in 16 different areas reliability and validity are very good and wellestablished World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule – II (WHODAS-II). Not updated in 10 years scoring of the WHODAS-II requires the use of a statistical scoring package such as SPSS Coming Soon Inventory of Psychosocial Functioning (IPF) Being developed by the VA's National Center for PTSD Developed with the help of veterans, who suggested much of the item content Normative sample is composed of veterans Measures psychosocial functioning across six domains: marital or other romantic relationships, family, work, friendships and socializing, parenting, education, and self-care. Functional Assessment Inventory (FAI). Advantages: available at no cost on internet content is more specific to the question of employability than any other instrument. Disadvantages No veteran normative samples Predictive validity of the instrument with regard to VBA rating decisions is not known. Green v. Derwinksi, 1 Vet. App. 121 at 125, 1991) We believe that fulfillment of the statutory duty to assist here includes the conduct of a thorough and contemporaneous medical examination, one which takes into account the records of prior medical treatment, so that the evaluation of the claimed disability will be a fully informed one. The courts have emphasized that an examiner’s reasoning contributes significantly to the probative value of his or her opinion. Therefore, taking time to write a cogent, persuasive Rationale section is vitally important. Nieves-Rodriguez v. Peake, 22 Vet. App. 295 at 306 (2008). “That the medical expert is suitably qualified and sufficiently informed are threshold considerations; most of the probative value of a medical opinion comes from its reasoning.” In Gambill v. Shinseki 576 F. 3d 1307 at 1311 (2009) the courts have signaled that submission of interrogatories is a distinct possibility. The more detailed the rationale, the less likely you will have to answer such interrogatories or the better prepared you will be for such postexam inquiries. In general, medical opinions that (a) do not indicate whether the psychologists or psychiatrist actually examined the veteran (b) do not provide the extent of any examination or (c) do not provide any supporting clinical data will be deemed inadequate (Claiborne v. Nicholson, 2005). Most important part of an opinion = the reasoning. “[A] medical examination report must contain not only clear conclusions with supporting data, but also a reasoned medical explanation connecting the two (Nieves-Rodriguez v. Peake, 2008a).” “Most of the probative value of a medical opinion comes from its reasoning. Neither a VA medical examination report nor a private medical opinion is entitled to any weight in a service connection or rating context if it contains only data and conclusions.” “[A] conclusion that fails to provide sufficient detail for the Board to make a fully informed evaluation” is inadequate. An opinion “must support its conclusion with an analysis that the Board can consider and weigh against contrary opinions.” Typical opinion request: ________is caused by or a result of______________ ________is most likely caused by or a result of ________ ________is at least as likely as not (50/50 probability) caused by or a result of ________ ________is less likely as not (less than 50/50 probability) caused by or a result of:_______ ________is not caused by or a result of _________ ________I cannot resolve this issue without resorting to mere speculation. DBQ opinion options: [ ] The claimed condition was at least as likely as not (50 percent or greater probability) incurred in or caused by the claimed in-service injury, event, or illness. [ ] The claimed condition was less likely than not (less than 50 percent probability) incurred in or caused by the claimed in-service injury, event, or illness. Nice but not compliant with Nieves-Rodriguez v. Peake, (2008) Based on my professional opinion as a board certified psychiatrist Based on a review of all the records and my clinical evaluation Based on current research the veteran’s XXX is not secondary to his service connected YYY Results of testing does not support the diagnosis The above opinion is based on review of the c-file records, clinical interview, treatment records, psychological testing, and DSM-IV Rationale should fully explain the underlying reason(s) supporting the opinion Specific research studies should be referenced Clear and concise without the use of jargon If the rationale is weak, send it back for clarification and supporting evidence It’s up to the examiner to communicate Its up to the rater to request clarification This Opinion Based on a review of the veteran’s files, my clinical interview, DSM-IV criteria, and my experience as a board certified psychiatrist, it is my opinion that this veteran’s PTSD is a result of his military service. OR Or This Opinion Although the veteran was diagnosed with PTSD by a treating mental health provider, the VA medical records do not support the diagnosis. The assessment of PTSD was made through the use of an unstructured interview with the veteran. Current research (see multiple references below) indicates that the use of a structured interview (e.g., CAPS) is significantly and statistically superior in assessing for PTSD versus an unstructured interview. The use of a measure like the CAPS, which is the "gold standard" in assessing PTSD, significantly improves the ability of an examiner to accurately diagnose PTSD. The CAPS has demonstrated reliability and validity (Weathers, Keane, & Davidson, 2001). It is important to assess for not only the presence of a symptom, but it is just as important to assess for the frequency and severity of a symptom. It is possible to have the existence of a PTSD-related symptom, but the symptom may not meet DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for persistence and severity to warrant the diagnosis of PTSD. The results of the CAPS (as well as clinical interview and psychological testing) did not support the diagnosis of PTSD. Cont. Speroff, T., Sinnott, P., Marx, B. P., Owen, R., Jackson, J. C., Greevy, R., Murdoch, M., Sayer, N., Shane, A ., Schnurr, P.A. (2011). Cluster randomized controlled trial on standardized disability assessment for service-connected posttraumatic stress disorder. Research abstract retrieved from http://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/meetings/2011/abstractdisplay.cfm?RecordID=301 Weathers, F. W., Keane, T. M., & Davidson, J. R. (2001). Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale: A review of the first ten years of research. Depression and Anxiety, 13(3), 132-156. Kashner, T. M., Rush, A. J., Surís, A., Biggs, M. M., Gajewski, V. L., Hooker, D. J., Shoaf, T., & Altshuler, K. Z. (2003). Impact of structured clinical interviews on physicians' practices in community mental health settings. Psychiatric Services, 54(5), 712-718. Miller, P. R., Dasher, R., Collins, R., Griffiths, P., & Brown, F. (2001). Inpatient diagnostic assessments: 1. accuracy of structured vs. unstructured interviews. Psychiatry Research, 105(3), 255-255-264. Rogers, R. (2001). Handbook of diagnostic and structured interviewing. New York, NY: Guilford Press. Rogers, R. (2003). Standardizing DSM-IV Diagnoses: The Clinical Applications of Structured Interviews. Journal of Personality Assessment, 81(3), 220-225. Segal, D. L., & Coolidge, F. L. (2007). Structured and semistructured interviews for differential diagnosis: Issues and applications. In M. Hersen, S. M. Turner, D. C. Beidel, M. Hersen, S. M. Turner, D. C. Beidel (Eds.) , Adult psychopathology and diagnosis (5th ed.) (pp. 78-100). Hoboken, NJ US: John Wiley & Sons Inc. Suppiger, A., In-Albon, T., Hendriksen, S., Hermann, E., Margraf, J., & Schneider, S. (2009). Acceptance of structured diagnostic interviews for mental disorders in clinical practice and research settings. Behavior Therapy, 40(3), 272-279. Erbes, C., Dikel, T., Eberly, R., Page, W., & Engdahl, B. (2006). A comparative study of posttraumatic stress disorder assessment under standard conditions and in the field. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 15(2), 57-63. Department of Veterans Affairs (2002). Best practice manual for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) compensation and pension examinations. Washington, D.C.: Author. Available at: http://www.avapl.org/pub/PTSD%20Manual%20final%206.pdf Worthen, M. D. & Moering, R. G. (2011). A practical guide to conducting VA compensation and pension exams for PTSD and other mental disorders. Psychological Injury and Law, 4(3-4), 187-216. Moering, R.G. (2011) Military service records: Searching for the truth. Psychological Injury and Law, 4(3-4), 217-234. Opinion Example The veteran’s Substance Use Disorder (alcohol dependence) is likely a result of the service connected PTSD. Multiple studies (see references below) have linked the use of alcohol to PTSD. Veterans who screened positive for PTSD or depression were two times more likely to report alcohol misuse relative to Veterans who did not screen positive for these disorders. The association between PTSD and alcohol abuse emphasized the clinical and public health importance of this relationship. The available evidence does support the causal nature of this relationship. Frequency and severity of PTSD symptoms“ were positively correlated with coping-motivated drinking ... and with alcohol use to forget. The re-experiencing and hyper-arousal PTSD symptom dimensions showed the strongest and most consistent correlations with the alcohol use indices" (Stewart et. al. 2004). (Cont. next slide) This opinion is also based on the veteran’s lay statement and review of multiple treatment records, there has been consistency related to the veteran’s substance abuse. There were no indications in the veteran’s service medical records or military personnel records to suggest any difficulties related to the use of alcohol until 1970 when he returned from Vietnam and had a DUI. Multiple medical records dating back to the 1970s clearly indicate ongoing alcohol abuse issues and multiple treatment program failures. Consistently (since 1970s) the veteran has indicated no substance abuse prior to military service or service in Vietnam. Given the substance abuse occurred after the traumatic stressor, it is likely a means for coping with symptoms associated with PTSD. Opinions and Rationales Driessen, M., Schulte, S., Luedecke, C., Schaefer, I., Sutmann, F., Ohlmeier, M., et al. (2008). Trauma and PTSD in patients with alcohol, drug, or dual dependence: a multi-center study. Alcoholism, Clinical And Experimental Research, 32(3), 481-488. Jakupcak, M., Tull, M., McDermott, M., Kaysen, D., Hunt, S., & Simpson, T. (2010). PTSD symptom clusters in relationship to alcohol misuse among Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans seeking postdeployment VA health care. Addictive Behaviors, 35(9), 840-843. Simons, J., Gaher, R., Jacobs, G., Meyer, D., & Johnson-Jimenez, E. (2005). Associations between alcohol use and PTSD symptoms among American Red Cross disaster relief workers responding to the 9/11/2001 attacks. The American Journal Of Drug And Alcohol Abuse, 31(2), 285-304. Stewart, S., Mitchell, T., Wright, K., & Loba, P. (2004). The relations of PTSD symptoms to alcohol use and coping drinking in volunteers who responded to the Swissair Flight 111 airline disaster. Journal Of Anxiety Disorders, 18(1), 51-68 C&P Opinion vs Treatment Opinion Whose opinion has more probative value? Only one mental health professional has diagnosed the veteran with PTSD. This professional did not administer a structured interview (e.g., CAPS); did not administer any objective testing (e.g., MMPI-2); did not review the veteran's claims file; did not follow the American Academy of Psychiatry and Law's "Practice Guideline for the Forensic Evaluation of Psychiatric Disability"; did not follow the American Psychological Association’s “Specialty Guidelines for Forensic Psychology,” and did not follow the VA's "Best Practice Manual for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Compensation and Pension Examinations" in reaching his diagnostic conclusions. The current C&P assessment approach is based on scientific evidence for its reliability and validity, e.g., use of the CAPS during C&P exams leads to "more complete, consistent, and accurate assessments" than unstructured interviews (Speroff, et al., 2011) and is consistent with the above published literature regarding conduct of these exams. C&P Opinion vs Treatment Opinion What did the Treating psychologist say? “Writer perused the record, and discovered that veteran has twice been administered the MMPI-2, which technically could be ruled as invalid. Veteran's reading level and reading comprehension levels were apparently not assessed prior to administration of those tests. Completion of the MMPI-2 typically requires at least an 8th to 10th grade education level, and the normative population tends to be somewhat better educated (e.g. 1-4 years of college, on the average)than that of much of the veteran population.” What happened? Remand back to C&P for another examination given the “new and material evidence” The Reality MMPI-2 Readability: The University of Minnesota Press (publisher)says the MMPI-2 requires a 5th grade reading level using the Lexile average or a 4.6 grade level using Flesch-Kincaid. Schinka and Borum (1993) indicated the MMPI-2 had overall reading levels at the 5th grade or lower” but also indicated a 6th grade level is a better Butcher (1991) found that the MMPI-2 reading level was at the 5th or 6th grade level. Shipley Institute of Living Scale is an intellectual functioning screener and does not assess reading comprehension as indicated by the treating provider. There are no research studies linking reading comprehension to the Shipley. Treating provider says the veteran didn’t have reading ability but he graduated from high school, was a helicopter mechanic in the army, and worked as a master electrician for 20 years. C&P examiners administered MENT, M-FAST, and SIRS-2. All showed significant exaggeration Treating provider never did a structured interview (CAPS) REFERENCES: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Federal Register: July 13, 2010 (Volume 75, Number 133)] [Rules and Regulations] [Page 39843-39852] From the Federal Register Online via GPO Access [wais.access.gpo.gov] [DOCID:fr13jy10-13] (retrieved on 08 February 2011) Department of Veterans Affairs (2002). Best Practice Manual for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Compensation and Pension Examinations. Washington, D.C.: Author. Kashner, T. M., Rush, A. J., Surís, A., Biggs, M. M., Gajewski, V. L., Hooker, D. J., Shoaf, T., & Altshuler, K. Z. (2003). Impact of structured clinical interviews on physicians' practices in community mental health settings. Psychiatric Services, 54(5), 712-718. Miller, P. R., Dasher, R., Collins, R., Griffiths, P., & Brown, F. (2001). Inpatient diagnostic assessments: 1. accuracy of structured vs. unstructured interviews. Psychiatry Research, 105(3), 255-255-264. Rogers, R. (2001). Handbook of diagnostic and structured interviewing. New York, NY: Guilford Press. Rogers, R. (2003). Standardizing DSM-IV Diagnoses: The Clinical Applications of Structured Interviews. Journal of Personality Assessment, 81(3), 220-225. Segal, D. L., & Coolidge, F. L. (2007). Structured and semistructured interviews for differential diagnosis: Issues and applications. In M. Hersen, S. M. Turner, D. C. Beidel, M. Hersen, S. M. Turner, D. C. Beidel (Eds.) , Adult psychopathology and diagnosis (5th ed.) (pp. 78-100). Hoboken, NJ US: John Wiley & Sons Inc. Suppiger, A., In-Albon, T., Hendriksen, S., Hermann, E., Margraf, J., & Schneider, S. (2009). Acceptance of structured diagnostic interviews for mental disorders in clinical practice and research settings. Behavior Therapy, 40(3), 272-279. Erbes, C., Dikel, T., Eberly, R., Page, W., & Engdahl, B. (2006). A comparative study of posttraumatic stress disorder assessment under standard conditions and in the field. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 15(2), 57-63. REFERENCES: 10. Weathers, F. W., Ruscio, A., & Keane, T. M. (1999). Psychometric properties of nine scoring rules for the Clinician-Administered Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Scale. Psychological Assessment, 11(2), 124-133. 11. King, J. & Sullivan, K. (2009) Deterring malingered psychopathology: The effect of warning simulating malingerers. Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 27(1), 35-49 12. Evans, K. & Sullivan, J. M. (1995). Treating addicted survivors of trauma. New York: Guilford Press. 13. Kofoed, L., Friedman, M.J., & Peck, R. (1993). Alcoholism and drug abuse in patients with PTSD. Psychiatric Quarterly, 64(2), 151-171. 14. Matsakis, A. (1992). I can't get over it: A handbook for trauma survivors. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications 15. Calhoun, Patrick S.; Earnst, Kelly S.; Tucker, Dorothy D.; Kirby, Angela C.; Beckham, Jean C.. (2000) Feigning Combat-Related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder on the Personality Assessment Inventory. Journal of Personality Assessment, 75(2). 338-350. 16. Dalton, John E. 1,2; Tom, Agnes 1; Roseblum, Mark L.; Garte, Sumner H. 1; Aubuchon, Ivan N. (1989) Faking on the Mississippi Scale for Combat-Related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1(1) 56-57. 17. Freeman, T., Powell, M., and Kimbrell, T. (2008) Measuring symptom exaggeration in veterans with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatric Research, 158(3) 74-80. 18. Frueh, B., Elhai, J. rubaugh, A., Monnier, J. Kashdan, T., Sauvageot, J., et al. (2005). Documented combat exposure of U.S. veterans seeking treatment for combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. The Bristish Journal of Psychiatry, 186, 467-472. 19. Doran v. Brown, 6 Vet. App. 283, 290-91 (1994) 20. Moreau v. Brown, 9 Vet. App. 389, 395 (1996) 21. Dizoglio v. Brown, 9 Vet. App. 163, 166 (1996) 22. Patton v. West, 12 Vet. App. 272 (1999) 23. YR v. West, 11 Vet. App. 393 (1998) REFERENCES: 24. Cohen v. Brown, 10 Vet. App. 128 (1997). 25. Menegassi v. Shinseki, No. 08-1895, 2010 WL 672785, at *3 (Vet. App. Feb. 26, 2010). 26. Smith, D. W., & Frueh, B. C. (1996). Compensation seeking, comorbidity, and apparent symptom exaggeration of PTSD symptoms among Vietnam combat veterans. Psychological Assessment, 8, 3–6. 26. Meyer, G.J., Finn, S.E., Eyde, L.D., Kay, G.G., Moreland, K.L., Dies, R.R., Eisman, E.J., Kubiszyn, T.W., Reed, G.M. (2001). Psychological testing and psychological assessment. A review of evidence and issues. American Psychologist, 56(2), 128-65. 27. DeViva, J. C., & Bloem, W. D. (2003). Symptom exaggeration and compensation seeking among combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 16, 503–507. 28. Dawes, R., Faust, D., & Meehl, P. (1989). Clinical versus actuarial judgment. Science, 243(4899), 1668-1674. 29. Ridgway, J.D. (2012). Mind Reading and the art of drafting medical opinions in Veterans benefits claims. Psychological Injury and Law, 4(304), DOI 10.1007/s12207-011-9113-4 30. Regier, D., Farmer, M., Rae, D., Locke, B., Keith, S., Judd, L. Goodwin, F. (1990). Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study. JAMA. 264(19), 2511. 31. Mueser, K., Drake, R., and Wallach, M. (1998). Dual diagnosis: a review of etiological theories. Addict Behav. 3(6). 717. REFERENCES: 32. Franklin, C., Repasky, S., Thompson, K., Shelton, S., & Uddo, M. (2002). Differentiating overreporting and extreme distress: MMPI-2 use with compensation-seeking veterans with PTSD. Journal of Personality Assessment, 79(2), 274-285. 33. Graham, J. R. (2006). MMPI-2: Assessing personality and psychopathology (4th Ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. 34. Nichols, D. S. (2001). Essentials of MMPI-2 assessment. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons 35. Resnick, P. J., West, S., & Payne, J. W. (2008). Malingering of posttraumatic disorders. In R. Rogers (Ed.), Clinical assessment of malingering and deception (3rd ed.) (pp. 109-127). New York, NY: Guilford Press 36. Tolin, D. F., Steenkamp, M. M., Marx, B. P., & Litz, B. T. (2010). Detecting symptom exaggeration in combat veterans using the MMPI–2 symptom validity scales: A mixed group validation. Psychological Assessment, 22(4), 729-736. 37. Morel, K. (2010) Differential Diagnosis of Malingering versus Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Scientific Rationale and Objective Scientific Methods. Nova Science Publishers, Inc., New York.