Vocal Fold Paralysis - Med Speech Voice & Swallow Center

advertisement

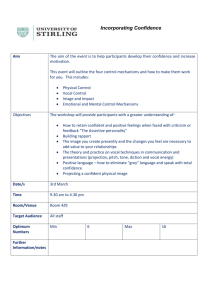

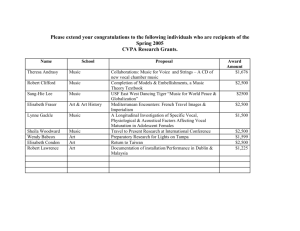

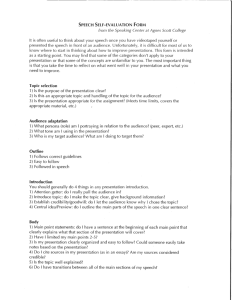

Vocal Fold Paralysis: A Dynamic Look at Treatment Presented by: Theresa Gorman Presented to: Rebecca L. Gould, MSC, CCC-SLP Brief Review Bilateral and unilateral vocal fold paralysis (VFP) disorders are caused by peripheral involvement of the recurrent laryngeal nerve branch and less commonly by damage to the superior laryngeal nerve. The site of the lesion along the nerve pathway will determine the type of paralysis, and the vocal quality that results from nerve damage. Etiologies of VFP Common etiologies of unilateral and bilateral vocal fold paralysis may include: surgical trauma (thyroid surgery, carotid artery surgery, anterior cervical fusion are some of the common surgical causes of the recurrent laryngeal nerve damage) cardiovascular disease neurological diseases accidental trauma (Glaze, Klaben & Stemple, 2000) Symptoms of VFP Typical symptoms include hoarseness, breathy voice, inability to speak loudly, limited pitch and loudness variations, voicing that lasts only for a very short time (around one second), choking or coughing while eating, and possible pneumonia due to food and liquid being aspirated into the lungs (McFarlane, Von Berg & Watson, 2001). Unilateral abductor paralysis Recurrent nerve damage - the paralyzed fold remains at midline, but the contralateral fold abducts and adducts normally, allowing both airway protection and quasi-normal speech and voice production. Because of midline positioning, the airway’s size will be reduced. Inspiratory stridor will likely be evident during arduous activity. Voice quality will remain normal but increased loudness will be difficult due to fold laxness of the paralyzed fold (Glaze et al. 2000). Unilateral adductor paralysis Recurrent nerve damage - This is most common type of fold paralysis - the affected fold rests in a paramedian (abducted) position whereas the contralateral fold abducts normally. This position and the vertical level of the fold, as well as the size of the glottal gap determine the effect of the paralysis on phonation. Voice quality is characterized by breathiness and diplophonia. The patient’s impaired ability to build subglottic pressure results in decreased vocal intensity and the inability to be heard in background noise, as well as regular physical fatigue (Glaze et al., 2000). Treatment Options…UVFP Voice therapy - techniques include hard glottal attack exercises, lateral digital pressure, head tilt method, Vocal function exercises, and half-swallow boom technique. These methods are utilized to reduce the vocal and laryngeal hyperfunction that results in an attempt to compensate for lack of glottic closure. Phonosurgery - Two surgical options used include medialization thyroplasty and laryngeal reinnervation. Medialization thyroplasty involves surgery to push the paralyzed vocal fold closer toward the middle so that the other vocal fold does not have to work so hard for the vocal folds to come together for voicing, and may be a helpful option when aspiration is persistent. It involves implantation of a small device, made from silastic or Gore-Tex, into the vocal fold to optimize its position for better closure during speaking and singing. Combination - because speech therapy, in isolation, is often ineffective. Beginning Treatment When the cause for vocal fold paralysis is known and it is determined that damage is permanent and there is no chance for return of function, then any form of management may begin immediately (Glaze, et al., 2000). When the cause is idiopathic, most surgeons will wait and observe the patient for 6-12 months before surgical intervention is applied. Other Options Reinnervation of the larynx involves surgery to connect another nerve to the larynx to replace the nerve that was damaged (Ford, 2005). The promise of laryngeal re-innervation has existed for years but has yet to be proven to be possible and effective (Rosen, 2003). The phonosurgical management alternatives for UVFP address the midline glottic incompetence and the loss of vocal fold body. Previously, the most widely used surgical option has been the use of a synthetic, alloplastic, Teflon paste into the lateral portion of the fold that is paralyzed, which transforms into a solid mass. This mass moves the paralyzed edge medially to improve midline function. This technique has been used for over 50 years, and has attained great success. Now…methods are different Teflon is no longer the preferred treatment method (complications - foreign-body granuloma and vocal cord stiffness). (Glaze et al., 2000). Silicone was reported to be a very safe material for injection laryngoplasty, but related adjuvant diseases halted its use. Autologous fat has been used for injection laryngoplasty because of its safety. It has a rapid absorption rate, which limits its long-term success; success may be increased by an overinjection of fat, initially, to compensate for the expected partial resorption. The technique’s advantages include that it is natural, soft, and flexible. The attributes of the autologous fat help it to vibrate well, while not posing any risk for antibody or foreign body response (Glaze et al., 2000). …New methods continued New bioimplants have been explored as injectable alternatives to Teflon. A cross-linked bovine collagen has been developed for injections. The bioimplant is injected superficially into the lamina propria of the vocal fold where it incorporates into the cellular structure of the fold and reportedly enhances the vibratory properties of the paralyzed fold, even where scarring is present. Patients, after lipoinjection, are placed on voice rest to enhance the survival of the transplanted fat. This is typically for 6-7 days in duration. No or minimal voice rest is used after laryngeal framework procedures or Teflon injection (Rosen, 2003). While injection laryngoplasty techniques become increasingly popular for vocal fold augmentation in cases vocal fold paresis, atrophy, and scarring, its role in the treatment of UVFP should be limited to cases with an appropriate glottal defect. …New methods continued In 1999, Zeitels described a new laryngeal framework procedure for UVFP called cricothyroid subluxation. This procedure involves anteriorly displacing the ipsilateral inferior cornu of the thyroid cartilage. This is performed by placement of a suture that runs from the inferior cornu of the thyroid cartilage to the midline of the cricoid cartilage. This effectively rotates the thyroid cartilage on the cricoid cartilage, providing additional length to the paralyzed vocal fold (Rosen, 2003). Surgical Management Complications poor voice outcome airway difficulties unwanted movement (migration) of the medialization implant surgical treatment for UVFP involves manipulation of the airway, so factors such as swelling or possible hematoma from either laryngeal framework surgery or vocal fold injection can cause airway difficulties – life threatening Current Behavioral Approaches It is comparable to physical therapy, but specifically targets the voice mechanism. The individual will work with the SLP on pitch alteration, increasing breath support and loudness, and finding the correct position for optimal voicing (such as turning the head to one side or manipulating the thyroid cartilage). Rosen (2003) explained that voice therapy is utilized as the primary treatment for those who have a favorable position of their vocal fold paralysis or are unwilling or unable to have surgery because of psychological or medical limitations. Therapy techniques include hard glottal attack exercises, lateral digital pressure, head tilt method, Vocal function exercises, and half-swallow boom technique. These methods are utilized to reduce the vocal and laryngeal hyperfunction that results in an attempt to compensate for lack of glottic closure (Glaze et al., 2000). Behavioral Treatment continued… Research continues to show professionals in our field that voice therapy is an effective intervention in the interim period between diagnosis of the paralysis and final resolution of the problem. Generally, voice therapy will improve voice function of patients with vocal fold paralysis by about 5 to 15 percent. Although this may not seem to be a dramatic improvement, for patients whose voice use is limited, or for those who do not wish to undergo surgery, it may represent a sufficient gain. Bilateral adductor paralysis (Recurrent Laryngeal nerve) BVFP occurs when fold are positioned laterally in an abducted paramedian position. The main concern becomes protection of the airway. This condition often requires that a patient have a gastrostomy tube for feeding due the insufficient airway protection. Bilateral abductor paralysis is a critical condition in which the folds are fixed at midline and cannot open. An adequate airway will be established surgically, often through a tracheostomy. Surgical manipulation of one arytenoids cartilage will also create sufficient airway by removing it completely or suturing it laterally. Bilateral paralysis is often medically treated and may require a tracheotomy to allow the person to eat safely. Superior Laryngeal Nerve damage Due to the shorter course through the body than the recurrent laryngeal nerves, superior laryngeal nerve paralysis occurs much less often. Etiologies of these paralyses include thyroid disease and thyroid surgery that cause temporary or permanent paralysis. Diagnosis is difficult to attain. Bilateral VFP (Superior laryngeal nerve) Bilateral paralysis is rare and must be confirmed through the use EMG studies. If paralysis occurs, vocal folds will lack their normal tone and will not lengthen sufficiently during increased pitch attempts. Voice quality is limited in frequency and intensity range and stability. Unilateral Superior Laryngeal Nerve VFP May result in an oblique positioning or an overlap of the folds because of the unequal rocking of the cricothyroid joint, which creates a gap between the folds and limits closure patterns. Vocal intensity is decreased due to the decrease in ability to build subglottic air pressure. Pitch is mainly affected. Patients often complain of vocal fatigue and inability to sing. No medical treatment exists, but voice therapy may be utilized for educational and voice conservation purposes. Unilateral Superior Laryngeal Nerve VFP A new alternative involves nerve-to-nerve reinnervation. Recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) to RLN reinnervation is not consistently successful because does not always provide functional return of the of adductor and abductor activity (Glaze et al., 2000). In addition, RLN-to-RLN anastomosis may result is dysphonia as a result of jerky movements and excessive synkinesis of adductor and abductor muscles simultaneously. The method is not heavily relied upon Futures Goals in Our Field It is important to understand that present surgical and medical treatments may only provide static improvement to the vocal fold and cannot provide the dynamic activity of the vocal fold to voice production that was present in the premorbid state. More to see in the future… The future goal of laryngology research will need to create a method of rehabilitation that is dynamic. This goal has been present for decades, and much work has been devoted to the concept of reinnervation of the vocal fold. Unfortunately, this type of work has been unsuccessful for most surgeons to date, and much research is required to better understand the delicate innervation of the muscles of the larynx and their coordination. The professionals in the fields of speech pathology and otolaryngology will strive towards that goal and actively perform new treatment approaches that prove efficacious. Pictures of Vocal Fold Paralysis Recurrent Laryngeal N. Paralysis Unilateral left vocal fold paralysis (Superior N. Paralysis) References Buckmire, R. & Kwon, T. (2004). Injection laryngoplasty for management of unilateral vocal fold paralysis. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surgery. 6, 538-542. Retrieved July 7, 2005, from PubMed database. Ford, C. N., (2005). Active Clinical Studies. Retrieved July 8, 2005, from University of Wisconsin Clinical Science Center site: http://www.surgery.wisc.edu/Oto/research/clinical_studies.shtml Glaze, L. E., Klaben, B. G., & Stemple, J. C. (2000). Clinical voice pathology: Theory and management. 3rd Ed. San Diego: Singular Publishing Group. Gray, S., Johnson, D., Kelly, S., Smith, M. (2004). Vocal fold paralysisand progressive cricopharyngeal stenosis reversed by cricopharyngeal myotomy. Retrieved July, 10, 2005, from http://uuhsc.utah.edu/otolaryngology/research.html#anchor9 McFarlane, S., Von Berg, S., Watterson, T., (2001). Vocal Fold Paralysis. Retrieved July 9, 2005, from http://www.asha.org/public/speech/disorders/vf_paralysis.htm Rosen, C. A., (2003). Vocal Fold Paralysis, Unilateral. Retrieved July 8, 2005, from http://www.emedicine.com/ent/topic347.htm Vocal Fold Paralysis. (n.d.). Retrieved July 10, 2005, from http://voicedisorders.upmc.com/VocalFoldParalysis/Treatment.htm