Taxation Guide – Addendum 1

advertisement

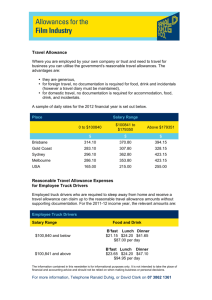

Taxation Guide – Addendum 1 Living Away From Home Allowance Introduction A living away from home allowance (LAFHA) benefit is a concept created by the fringe benefits tax legislation. How does the Commissioner define it? His views are set out in miscellaneous tax ruling MT 2030 as follows: “. A living-away-from-home allowance exists where it is reasonable to conclude from all the surrounding circumstances that some or all of the allowance is in the nature of compensation to the employee for additional expenses incurred, or additional expenses incurred and other disadvantages suffered, because the employee is required to live away from his or her usual place of residence in order to perform the duties of employment. Additional expenses do not include expenses for which the employee would be entitled to an income tax deduction. “ And further: “The whole or such part of the allowance as satisfies these tests is a living-away-from-home allowance fringe benefit, the taxable value of which is calculated in accordance with the rules contained in section 31. The taxable value is so much of the allowance as qualifies as a living-awayfrom-home allowance fringe benefit reduced by either or both of two components being the "exempt accommodation component" and the "exempt food component". Both of these terms are defined in section 136 of the Act.” And: “The exempt accommodation component is so much of the allowance as it is reasonable to conclude is in the nature of compensation for additional expenses on accommodation that the employee could reasonably be expected to incur. The exempt food component is so much of the allowance as is reasonable compensation for additional expenses on food. It is arrived at by first ascertaining the "food component" of the allowance, as defined in section 136. The food component is so much of the allowance as is in the nature of compensation for expenses the employee could reasonably be expected to incur on food and drink. “ A LAFHA benefit then, is a benefit paid in circumstances where an employee is living away from home and an allowance is paid to the employee as compensation for additional expenses incurred because the employee is required to live away from his or her usual place of residence to perform the duties of employment. In general, there must be an intention or expectation that some form of compensation will be provided to the employee. The statutory incidence of the tax falls on the employer. Some aspects are tax exempt – exempt food and exempt accommodation – and are not subject to fringe benefits tax. If a payment does not qualify as a living away from home allowance it is taxed to the employee on a normal wages basis. Whether an allowance paid to an employee qualifies as a LAFHA is determined on the facts of each particular case. A number of indicators have been outlined by the ATO to assist employers. As a general guide, if the period spent away by the employee is more than 21 days, an allowance should be treated as a LAFHA. The following paragraphs are extracted from the Commissioner’s ruling: “As the decisions illustrate, the question whether an employee is living away from his or her usual place of residence normally involves a choice between two places of residence, i.e., the place where the employee is living at the time or some other place. A person is regarded as living away from a usual place of residence if, but for having to change residence in order to work temporarily for his employer at another locality, the employee would have continued to live at the former place. It would be relevant in reaching that view that there is an intention or expectation of the employee returning to live at the former place of residence on cessation of work at the temporary job locality. This would be relevant even if the employee is living in temporary quarters close to a temporary job site. Reference is made to the following decisions by way of illustration. A Journalist transferred between capital cities The facts of Board of Review Case 88 1 TBRD 353, were that the taxpayer had been compulsorily transferred in his work from one capital city to another, a transfer he was bound to accept under the terms of his employment. The taxpayer brought his family to live with him in the new city. The Board of Review found, on the facts, that he had changed his place of abode and was not living-away-fromhome. B Factory technician in a country town The taxpayer in Case B47 2 TBRD 201, maintained a home in Perth where his wife lived for a period of 6 years while he worked in a town 130 miles away, staying in hotel accommodation and returning home each weekend and for holidays. The Board of Review found that his home in Perth was more permanent and was his "usual" place of abode. C International airline pilot An allowance paid to the taxpayer to enable him to maintain his standard of living while on a 2 year posting to London was accepted by the Board of Review in this case - 12 CTBR (NS) Case 106 - as a living-away-from-home allowance. The Board found persuasive in concluding that the taxpayer was living away from his usual place of abode that the overseas appointment was of fixed maximum duration, that he would ordinarily have continued to live at his Australian home but for the posting and that he expected to return there to live at the end of the posting. D Construction worker : transitory lifestyle In another case decided by a Board of Review, S.27 85 ATC 270, although the taxpayer was paid what was described on his group certificate as a living-away-from-home allowance, the Board found that he had no usual place of abode other than the flat, house or residence where he ate and slept in proximity to his work place. The construction site was near a country town 200 kilometres from a capital city. Because of what it found to be "the transitory nature of the taxpayer's lifestyle" - he had changed addresses 3 or 4 times to change jobs in the previous 8 or 9 years and had abandoned the flat he had lived in prior to his construction site employment - the Board did not accept that he was living away from his usual place of abode. An underlying theme of the cases is a general presumption that a person's usual place of residence will be close to the place where he or she is permanently employed. Correspondingly, an employee who changes his or her place of residence because of a change in the location of a permanent job, whether by reason of a transfer with the same employer or a change of employment, would not usually be living away from home on moving to a new place of residence close to the new job location. That would be the case notwithstanding that the new place of residence was a temporary one pending the obtaining of suitable long term accommodation. Employees who move to a new locality to take up a position of limited duration with an intention to return to the old locality at the end of the appointment would generally be treated as living away from their usual place of residence. For example, a construction worker having to travel to a construction site to live and work would be in this category unless he had abandoned the former place of residence upon moving to the locality of the site. A case of the latter situation would be where the employee decided to permanently leave the former home, e.g., if a resident of Sydney, on obtaining a job for two years on a construction site in a remote part of Western Australia, decided to "sell up" in Sydney and move permanently to Western Australia to live. “ Where an employee is required to travel to perform part of their job any allowance is covered under deductibility and travel allowance provisions of tax law. The importance of this distinction to employers is that a LAFHA is considered a fringe benefit, and the tax liability resides with the employer. A travel allowance is part of an employee’s assessable income, and whether or not it is a tax deduction is a matter for the individual employee to ascertain. An employee must be considered to be living away from their usual ‘place of residence’. ‘Place of residence’ generally means accommodation, permanent or temporary, where the employee would reside, and would continue to reside, but for having to change residence in order to work temporarily for his employer at another locality. The case law does indicate that there must be an intention or expectation of the employee to return to live at the former place of residence. When this expectation or intention changes, the employee is no longer entitled. It is important to note that an allowance paid to an independent contractor is not classified as a LAFHA. Therefore, it forms part of the consideration for that entity’s taxably supply of services under the GST Act. However if the activities are carried out by an employee, or through duties similar to those carried out by an employee, an allowance that can be defined as a LAFHA benefit is not taxable under the GST Act. It is advisable that any allowance is paid by the employer closest to the employee/contractor. This is referred to in ATO Interpretive Decision 2002/300. The FBT legislation defines an employee as either a current, former or future employee who has or will received salary or wages. Salary or wages is also defined as payment from which an amount must be withheld under tax legislation. In the case of employment agency, where an employee is required to work and reside outside of the area prescribed in their employment contract, for a period greater than 21 days, an allowance may be considered a LAFHA. A 2007 decision of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal found that allowances paid by a labour hire company supplying labour to an offshore oil rig were LAFHA benefits, as the company was considered the employer for FBT purposes. This decision supports the argument that an employee of an employment agency is entitled to LAFHA when living away from their usual place of residence. However any allowance is made subject to the provision of FBT legislation. This includes exemptions for food and accommodation. The table value of a LAFHA is the amount paid less either or both the exempt accommodation and food components. Food Component The food component is required to be determined before payment. Calculating what is taxable and what is not is complicated and messy. The food component, however the amount must be reasonable and based in some reality. When determining a reasonable food component factors such as the usual food expenditure of the employee, the cost of food at the alternate location, and the composition of the employee’s family are relevant factors. If the food component allowance exceeds the notional statutory food amount of $42 per adult and $21 per child, the excess amount is tax exempt. But the excess must bear some semblance to amounts actually spent and not be arbitrary. An employer should identify a reasonable allowance and deducts the statutory food amount from the LAFHA before it is paid. This will enable the exempt amount to be identified (as the excess over the statutory notional amount per employee and family member). Where an employer calculates the estimated home food cost to be less than the statutory food amount, the calculations become difficult. The food component reduced by the amount by which the statutory food amounts exceed the estimated food costs is the exempt food component. If the food component for a single person has been set at $100.00 after allowing for estimated home food costs of $30.00, the exempt food component is $100 minus ($42.00 being the statutory amount minus $30.00 equals $88.00. Accommodation Component The accommodation component is the amount an employee could reasonably be expected to incur at the alternate location. There are no strict guidelines to enforce the reasonableness of accommodation costs. However, the ATO outlines a number of factors to take into account: whether the employee will be accompanied by family members the position held by the employee in the workplace the location where the employee will be living whether or not the accommodation will be furnished the employee's current living standards. The following examples are also given by the ATO to determine accommodation costs: using the accommodation expenditure for an employee with similar circumstances in the alternate location using indexes and guidelines provided by the Australian Bureau of Statistics or commercial organisations to estimate the costs of accommodation in a particular location. This amount will be tax exempt. However it is important to note that any amount not considered reasonable will be included in the taxable value of the LAFHA. Employee Declaration To qualify for the food or accommodation component exemptions, an employee must give a declaration to the employer stating the employee’s usual place of residence and the place at which the employee actually resided during the period during which the LAFHA benefit is created. This declaration must be provided before the exemption can be applied to the taxable value of the LAFHA. Other Components All other LAFHA components are taxable as fringe benefits. Allowances paid to attract or retain employees in a location that are calculated without regard to reasonable additional living expenses will not be LAFHA benefits. Such allowances may include the provision of accommodation. Such allowances would be taxable to the employee on a wages basis. A copy of the Commissioner’s ruling – MT 2030 – is annexed.