here - University College London

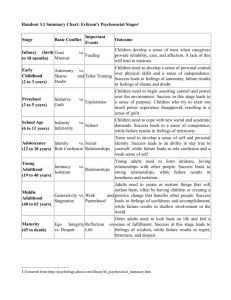

advertisement

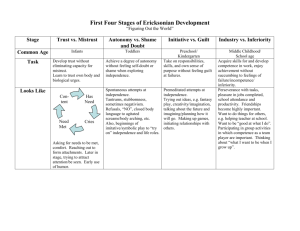

Disruptive behaviours at school: Information processing differentiators of callous-unemotional traits and conduct problems Chloe Booth Developmental Risk & Resilience Unit, Department of Psychology & Language Sciences, UCL Introduction Results Children with disruptive behaviours are at risk for low academic achievement and developing life-course persistent antisocial behaviour (Viding et al., 2009). Although two children with conduct problems (CP) may manifest similar disruptive behaviours, these behaviours could be driven by different underlying vulnerabilities and thus require different interventions. Callous-unemotional (CU) traits are one of the best researched markers of different causal pathways to antisocial behaviour (Frick & Viding, 2009) and can be used to distinguish between children who are capable of pre-meditated antisocial behaviour (CP/CU+) and children whose antisocial behaviour is more impulsive and threat reactive (CP/CU-). The TOSCA data was first inspected for outliers. Five participants who had an extreme score of +/- 3 standard deviations from their group mean were removed from the analysis, leaving 19 participants in the CP/CU+ group, 16 participants in CP/CU- group, and 26 participants in the comparison group. Researchers have suggested that two developmental pathways to disruptive/antisocial behaviour may exist, one involving low levels of guilt and empathy and another involving heightened shame (Eisenberg, 2000; Frick & Viding, 2009). Guilt is believed to be critical for moral actions and the development of conscience, whereas shame has been shown to be positively correlated with antisocial behaviour. Thus, whereas guilt is known to promote moral and reparative behaviour, high levels of shame appear to act in an opposite way (e.g. Tangney, 1998). This study examined guilt and shame responding in a community sample of adolescents who were grouped according to their level of CP and CU. Two vignette based measures were used. We predicted that CP/CU+ group would show lower levels of guilt responding and that that CP/CU- group would show higher levels of shame responding as compared with ability matched comparison children. Materials and methods Adolescents aged 11-13 years old were recruited from mainstream comprehensive secondary schools using opportunity sampling. Study groups were screened from this sample based on questionnaire and ability data (final N=66). All groups were matched for age, gender and IQ (FSIQ of Wechsler Abbreviated Scales of Intelligence; Wechsler, 1999): Mixed model ANOVA was conducted on the TOSCA measure: Mixed model ANOVA was conducted on the TOSCA measure: • There was a significant (F(2, 61)=4.34 p<0.05). • There was a significant main effect of group (F(2, 58)=4.98, p<0.01). • There was a significant (F(1, 61)=12.15 p<0.001). • There was a significant main effect of emotion (F(3, 174)=83.32, p<0.001). • There was a significant group x emotion interaction (F(6, 174)=7.33, p<0.001). • Questionnaire of Subjective Emotions (QSE; Burnett, 2006) - A self-report measure with eight short scenarios used to examine the intensity of guilt and shame felt following imagined transgressions. main effect effect of of group emotion Planned comparisons, corrected for multiple comparisons (See Fig. 2): Planned comparisons were also run using independent samples t-tests corrected for multiple comparisons (See Fig. 1): Guilt • CP/CU+ group showed less guilt than comparison group (t(45)=-3.953, p<0.001; d’=1.13). Guilt • AB/CU+ group scored less than the comparison group for guilt (t(45)=-2.958, p<0.01; d’=0.84). • CP/CU- individuals did not score significantly differently on guilt items than the comparison group (p=.76). • CP/CU- group did not significantly differ from the comparison group (p=.52). Shame • For shame, CP/CU+ group did not significantly differ from the comparison group (p=.16). • CP/CU- group showed more shame than the comparison group (t(41)=2.466, p<0.02; d’=0.75). These results show that in the TOSCA task CP/CU+ individuals displayed less guilt than comparison children, but CP/CU- individuals did not significantly differ from the comparison group. For shame, CP/CU+ individuals did not significantly differ from the comparison group, but CP/CU- individuals showed more shame responding than the comparison group Scores by group on Guilt and Shame items from the Test Of Self-Conscious Affect • CP groups scored in the top tertile of the sample for CP (indexed by a combination score on the Conduct Disorder and Oppositional Defiant Disorder Scales of the Adolescent Symptom Inventory, Gadow & Sprafkin, 1997). • These participants were further divided into CU+ (N=20) and CU- (N=18) groups using a median split on Inventory of Callous Unemotional Traits (ICU; Frick, 2003). Measures • Test of Self-Conscious Affect (TOSCA-3; Tangney, Dearing, Wagner, & Gramzow, 2000) - A self-report measure designed to examine shame- and guilt-proneness. Participants rate the likelihood of responding in a particular way following each scenario. main • However there was no statistically significant group x emotion interaction (F(2, 61)=0.253 p=0.777). This study suggests that different moral emotion processing profiles may explain why different subgroups of children with disruptive/antisocial behaviours can find it difficult to perform reparative actions and behave in a morally acceptable way. Disruptive behaviours performed by CP/CU+ individuals may be attributable to low guilt, making it easier for them to continue aggressing against other people. Lack of guilt may also prevent children with CP/CU+ from performing reparative actions after transgressions and thus lead to continued behavioural problems. This study also suggests, albeit in a less clear-cut fashion, that CP/CU- may be associated with excessive shame, which could result in avoidance of addressing one’s disruptive behaviours. These results have implications for interventions that address disruptive behaviours. As children with CP are a heterogeneous group with different pathways leading to disruptive behaviours, the most successful types of intervention will be those that are individualised for the particular risky behaviour that the child is displaying, targeting specific information and affective processing styles. For example, interventions for CP/CU+ should capitalise on socially acceptable rewards and seek to boost the weak ability to empathise. Conversely, CP/CU- children may benefit from school programmes that teach about controlling emotions and managing aggression. Shame • For shame items, there were no significant differences between CP/CU+ and comparisons (p=.11). • There was no significant differences between CP/CU- and comparisons (p=.68). Literature cited Similar to the TOSCA findings, CP/CU+ individuals showed less guilt responding, but CP/CU- individuals did not differ significantly from comparison group on the QSE measure. However, for shame items, there were no significant differences between any of the groups on the QSE measure. It is unclear what drives the discrepant finding for shame in CP/CU- group in the two tasks. It could be that the TOSCA task is more sensitive in measuring excessive shame attributions because it does not directly ask about feeling ashamed. Scores by group on Guilt and Shame items from the Questionnaire of Subjective Emotions 35 55 • Comparison group (no CP and low CU scores) was also selected (N=28). Outlier inspection of the QSE data revealed two participants who had an extreme score of +/- 3 standard deviations from their group mean. These individuals were removed from the analysis, leaving 20 participants in CP/CU+ group, 17 participants in CP/CU- group, and 27 participants in the comparison group. Conclusions Burnett, S. (2006). The Questionnaire of Subjective Emotions. Unpublished rating scale, University College London. Eisenberg, N. (2000). Emotion, regulation, and moral development. Annual Review of Psychology, 51, 665-697. Frick, P. J. (2003). The Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits. Unpublished rating scale, University of New Orleans. Frick, P. J. & Viding, E. (2009). Antisocial behavior from a developmental psychopathology perspective. Development and Psychopathology 21, 1111-1131. Gadow, K. D., & Sprafkin, J. (1997). Adolescent Symptom Inventory 4: Screening Manual. New York: Checkmate Plus. Tangney, J. P. (1998). How does guilt differ from shame? In J. Bybee (Ed.), Guilt and children (pp. 1-17). San Diego: Academic Press. Tangney, J. P., Dearing, R., Wagner, P. E., & Gramzow, R. (2000). The Test of SelfConscious Affect – 3 (TOSCA-3). Fairfax, VA: George Mason University. Viding, E., Simmonds, E., Petrides, K. V., Frederickson, N. (2009). The contribution of callous-unemotional traits and conduct problems to bullying in early adolescence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 50(4), 471-481. 50 Wechsler, D. (1991). Wechsler Intelligence Scales for Children - Third Edition. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. 30 45 40 CP/CU+ CP/CUComparison TOSCA Score 35 30 QSE 25 Score CP/CU+ CP/CUComparison 20 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Essi Viding for supervising this project and Carol Cuthell for her help in recruiting participants. For further information 25 Please contact chloe.booth.09@ucl.ac.uk or e.viding@ucl.ac.uk 20 More information on this and related projects can be obtained from the Developmental Risk and Resilience Unit website: http://www.ucl.ac.uk/clinical-psychology/Research-Groups/DVR 15 Guilt Shame Figure 1. Scores by group on Guilt and Shame items from the Test Of Self-Conscious Affect measure. Note: CP/CU+ = Conduct Problems with Callous-Unemotional traits; CP/CU- = Conduct Problems without Callous-Unemotional Traits. Guilt Shame Figure 2. Scores by group on Guilt and Shame items from the Questionnaire of Subjective Emotions. Note: CP/CU+ = Conduct Problems with Callous-Unemotional traits CP/CU- = Conduct Problems without Callous-Unemotional Traits. This poster can be found online at www.ucl.ac.uk/~ucjtchb