Julius Caesar

advertisement

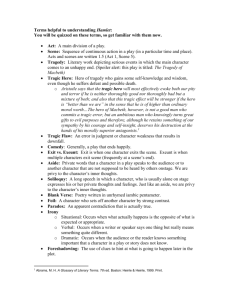

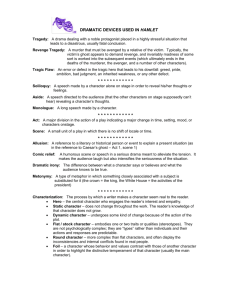

An Introduction to Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar Tragedy Tragedy is the branch of drama, first developed in Ancient Greece, which deals with sorrowful or terrible events in a serious and dignified style. Every tragedy asks fundamental questions about the nature of humanity, the universe, and God. The central theme of every tragedy is concerned with defining the nature evil and explaining its existence in the universe. The appeal of tragedy to the human mind lies in examining evil as a force that is external (lying outside of ourselves) and internal (originating from our own hearts and minds). One of the greatest examples of Greek tragedy is Oedipus Rex, written by Sophocles in the fifth century B.C. Aristotle, a Greek philosopher, defined tragedy as a “dramatic action containing incidents which arouse pity and fear, wherewith to accomplish a cleansing of such emotions”. He also stated that the tragic hero must not be all good or all bad, but somewhere in between. His misfortune is brought about by some error of judgment caused by his tragic flaw. The tragic hero cannot blame the gods but must take responsibility for his own downfall. Shakespearean (or Renaissance) tragedy is modeled on many of the conventions of the Greek tragedy. Here are the chief characteristics of tragedy: The Cult of the Hero: A man lived for honour and renown. His life was one of courageous and glorious action played out in a world of great men. The hero’s life would reach its climax in a great and noble death. The Greek hero was an extraordinary man, completely devoted to the pursuit of honour which could be accomplished by making a great sacrifice for his people. The Supernatural World: In Greek tragedy, the gods send suffering and evil into the world and help to bring about the downfall of the tragic hero (though he also contributes to his own misfortune as well). Shakespeare often included elements of the supernatural (ghosts and witches) and abnormal conditions of the mind (insanity, hallucination, sleepwalking). There is a conflict between free will (the hero’s ability to make a choice and to assume responsibility for that choice) and fate (the action of forces that are far more powerful than man.) Both external and internal conflicts are included, but the internal conflict is most important as we see a battle in the tragic hero’s heart and soul. A hundred years after Sophocles wrote Oedipus Rex, Aristotle composed a book called the Poetics in which he presented his theory of poetry and drama. These terms are also used in the study of Shakespearean tragedies: Hamartia: Another word for the hero’s “tragic flaw” or “fatal flaw”. Aristotle believed that the tragic hero committed an offense because he was in ignorance of an important fact, not because he was evil or had a moral flaw. It was only the later influence of Christianity which made man totally responsible for his actions and which redefined the tragic flaw as a personal or character flaw such as ambition, greed, or jealousy. Hubris: Excessive pride within the tragic hero, especially evident when he attempts to defy fate and control his own destiny. To fight against the will of the gods or Fate was a recipe for disaster. Nemesis: The agents of justice which bring about the hero’s deserved punishment. The Christian values of the Elizabethans dictated that sin against God would result in just punishment. Pathos: The emotions of pity, fear, and sadness aroused in the audience as we observe the wasted human potential of the tragic hero. Catharsis: The effect that tragedy should have on the audience by purging and cleansing of our own dark desires and fears. The Greeks believed that by watching the misfortunes of the hero, we could confront our own flaws and fears (loss of love, family, friends, money, power, or life itself) and overcome them. This involves identifying with the hero and realizing that his problems are universal. Characteristics of the Tragic Hero Must be a man of noble stature. He is an extraordinary and admirable man (hence often a king). Though he is great, he is not perfect. He has a moral defect known as a TRAGIC FLAW. He works to achieve a goal that is very dear to him. This action involves him in a number of CHOICES which throw him into significant INTERNAL CONFLICT. As a result of his choices, he gets caught in a web of circumstance. This sets up a chain of events the tragic hero could not or would not see and which cannot be halted. He is thus CAUGHT IN HIS DESTINY. When it is too late, he realizes what has happened to him and he dies bitter and burnt out. The hero’s poor choices often bring about disorder in society. Shakespeare assumes there is an order in the universe which we dare not disturb. If this order is broken, chaos and disorder will reign; however, counter forces will be set in motion to re-establish order. This order usually returns at the end of the play as a result of the tragic hero’s death. Key Themes in Julius Caesar: Fate versus Free Will Julius Caesar raises many questions about the force of fate in life versus the capacity for free will. Ultimately, the play seems to support a philosophy in which fate and freedom maintain a delicate coexistence. Overall though, the play suggests that we should never completely depend on fate or surrender our capacity for freedom and choice. Public Self versus Private Self Much of the play’s tragedy stems from the characters’ neglect of private feelings and loyalties in favor of what they believe to be the public good. Similarly, characters confuse their private selves with their public selves, hardening and dehumanizing themselves or transforming themselves into ruthless political machines. Appearances verses Reality Much of the play deals with the characters’ failures to interpret correctly the omens that they encounter or the intentions of the people they meet. In the world of politics portrayed in Julius Caesar, the inability to read people and events leads to downfall; conversely, the ability to do so is the key to survival. Ambition and Conflict The ambition of great men can lead to their downfall and to virtual anarchy within an entire country. Great ambition leads to great conflict. Rhetoric and Power (rhetoric - the art of using words effectively in speaking and writing) Julius Caesar gives detailed consideration to the relationship between rhetoric and power. The ability to make things happen by words alone is the most powerful type of authority. Honour Shakespeare explores the concept of what honour entails. This is seen primarily through the character of Brutus, since the code of honour is the guiding principle of his life. Though we admire Brutus for his idealism, Shakespeare seems to be saying through him that blind adherence to the concept of honour without using common sense can only lead to disaster. Order/Obedience verses Chaos/Rebellion The crux of Julius Caesar is a political issue that was as urgent in Shakespeare's Elizabethan England as it was in Caesar's day. It revolves around the question of whether the killing of a king is justifiable as a means of ending (or preventing) the tyranny of dictatorship and the loss of freedom. Shakespeare seems to suggest in his plays that rebelling against legitimate authority will lead to chaos and destruction. Loyalty and Friendship Throughout the play, characters must decide whether or not to be loyal to their friends. Disloyalty is a disease that can threaten an individual and an entire country. The play teaches that friendship matters more than abstract principles or vain ambitions. Motifs: A motif is an element, usually symbolic, that recurs in creative work. The Sleep Motif: Shakespeare reinforces the idea that a guilty conscience never sleeps. Kodie never sleeps Omens: Throughout the play, omens and portents manifest themselves, each serving to crystallize the larger themes of fate and misinterpretation of signs. Characters repeatedly fail to interpret the omens correctly. In a larger sense, the omens in Julius Caesar thus imply the dangers of failing to perceive and analyze the details of one’s world. Bird/Animal Imagery – People are often compared to birds or animals to reveal character. Birds may also be used as important symbols. Dramatic Conventions: SOLILOQUY – A speech delivered by a character in a play when he/she is alone on stage; it creates a dramatic moment in the play and is used to reveal the character’s inner thoughts. ASIDE- A comment made by an actor on stage meant for the audience to hear and not the other actors. It serves to involve the audience more in the performance, as it reveals the speaker’s innermost thoughts. ANACHRONISM – Placing an event, person, item, or verbal expression in the wrong historical period. In Shakespeare's Julius Caesar, Shakespeare writes the following lines: Brutus: Peace! Count the clock. Cassius: The clock has stricken three (Act II, scene i, lines 193-94). Literary Devices: ANTITHESIS - Using opposite words or phrases in close conjunction. Ex: "I burn and I freeze," or "Her character is white as sunlight, black as midnight." The best antitheses creates a contrast of opposites in a balanced sentence. Ex: "Evil men fear authority; good men cherish it." ALLUSION - is an indirect reference to a well-known event, person, thing, or place. Allusions are not explained explicitly and are dependent on a reader’s prior knowledge. There are five types: Literary: involves a reference to another work of literature Biblical: involves a reference to people and events from the Bible Historical: involves a reference to people and events from history Classical: involves a reference to people, events, or literature from the world of the ancient Romans and Greeks Cultural: involves a reference to elements of popular culture COUPLET - Two lines--the second line immediately following the first--of the same metrical length that end in a rhyme to form a complete unit. DRAMATIC IRONY - This occurs when the reader knows something of which the character(s) is (are) unaware. The reader is said to have superior knowledge. A story may have reverse dramatic irony when an author withholds information from the reader of which the characters may be aware. VERBAL IRONY - This type of irony is very close to sarcasm and occurs when the author or character says one thing but means the opposite. It is often used in a cutting way or to ridicule. SYMBOL - A word, place, character, or object that means something beyond what it is on a literal level. Ex: In “Cranes Fly South”, the flight of the cranes symbolizes the passage from life to death. PATHETIC FALLACY – When nature or elements of the physical environment appear to be in sympathy with or affected by events in the human world. For example, after King Duncan’s death in MacBeth the sun refuses to shine, the earth quakes, and windstorms ravage the countryside. Other Key Terms: SENNET - A call on a trumpet or cornet signaling the ceremonial exits and entrances of actors in Elizabethan drama. SENATE -An assembly or a council of citizens having the highest legislative functions in a government. CAPITOL - A building or complex of buildings in which a state legislature meets. CAPITAL - A town or city that is the official seat of government in a political entity, such as a state or nation. COLOSSUS - A huge statue. TIBER- A river of central Italy flowing about 406 km (252 mi) south and southwest through Rome to the Tyrrhenian Sea at Ostia. IDES - The 15th day of March, May, July, or October or the 13th day of the other months in the ancient Roman calendar. CONSUL- Either of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, elected for a term of one year. DRACHMA -An ancient Greek silver coin.