EKPHRASES

advertisement

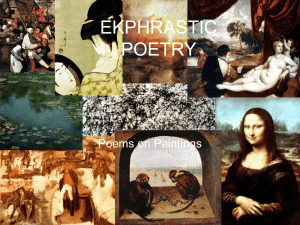

EKPHRASTIC POETRY Poems on Paintings Ekphrasis Ekphrasis is the graphic and rhetorical description of a visual work of art. Ekphrastic poetry is poetry that focuses on works of art to “to interpret, inhabit, confront, and speak to their subjects.” (“Ekphrasis,” Poets.Org) “Ekphrasis: Poetry Confronting Art” from Poets.Org: http://www.poets.org/viewmedia.php/prmMID/5918 Wikipedia article on Ekphrasis: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ekphrasis The Lady and the Unicorn tapestry, c.1500, Flanders,, the Musée de Cluny, Paris Jorie Graham, "The Lady and the Unicorn and Other Tapestries" If I have a faith it is something like this: this ordering of images within an atmosphere that will receive them, hold them in solution, unsolved. It is this: that the quail over the snow on our back field run free and clocklike, briefly safe. That they rise up in gusts, stiff and atemporal, the moment a game they enter, held in place, as prey, by goodness, by their role in the design. And when they rise, straight up, to this or that limb in the snowfat fir, they seem -- because the body drops so far below its wings -to also fall, like our best lies that make what's absolutely volatile look like it's weighted down -- our whitest lie, the beautiful . . . . They rise up in the falling snow and yet to see them is to see their fallenness . . . . And when, each to their limb they go, their faces taupe and indigo and peeking gently out from under hats like thread and needle starting to pull in the simple fear, it is an ancient tree their eager eyes map out -playful and vengeful and symmetry-bound: where out of love the quail are woven into tapestries, and , stuffed with cardamon and pine-nuts and a sprig of thyme. Leonardo da Vinci, Mona Lisa (c.1503) Oil on panel, approximately 30 inches x 21 inches. Louvre, Paris. John Stone, “Three for Mona Lisa” 1 It is not what she did at 10 o'clock last evening accounts for the smile. It is that she plans to do it again tonight. 2 Only the mouth all those years ever letting on. 3 It's not the mouth exactly it's not the eyes exactly either it's not even exactly a smile But, whatever, I second the motion. Pieter Brueghel the Elder, Two Monkeys (1562) Oil on canvas, approximate ly 8 inches x 9 inches. Dahlem Museum, Berlin. Wislawa Szymborska “Two Monkeys by Brueghel” (trans. from the Polish by Magnus Kryski) I keep dreaming of my graduation exam: in a window sit two chained monkeys, beyond the window floats the sky, and the sea splashes. I am taking an exam on the history of mankind: I stammer and flounder. One monkey, eyes fixed upon me, listens ironically, the other seems to be dozing-and when silence follows a question, he prompts me with a soft jingling of the chain. Pieter Brueghel, Kermesse (1567-8) Oil on canvas, approximately 45”x64.5”. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. William Carlos Williams, “The Dance” In Brueghel's great picture, The Kermess, the dancers go round, they go round and around, the squeal and the blare and the tweedle of bagpipes, a bugle and fiddles tipping their bellies (round as the thicksided glasses whose wash they impound) their hips and their bellies off balance to turn them. Kicking and rolling about the Fair Grounds, swinging their butts, those shanks must be sound to bear up under such rollicking measures, prance as they dance in Brueghel's great picture, The Kermess. Pieter Brueghel, The Fall of Icarus Oil-tempera, 29 inches x 44 inches. Museum of Fine Arts, Brussels. W.H. Auden, “Musee des Beaux Arts” About suffering they were never wrong, The old Masters: how well they understood Its human position: how it takes place While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along; How, when the aged are reverently, passionately waiting For the miraculous birth, there always must be Children who did not specially want it to happen, skating On a pond at the edge of the wood: They never forgot That even the dreadful martyrdom must run its course Anyhow in a corner, some untidy spot Where the dogs go on with their doggy life and the torturer's horse Scratches its innocent behind on a tree. In Breughel's Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry, But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green Water, and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky, Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on. Titian, Venus and the Lute-Player (1560-65) Oil on canvas, 65 “ x 82.5 “ Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City. Far in the background a blue mountain waits To echo back the song The note-necked swan, while it reverberates, Paddles the tune along. The player is a young man richly dressed. His hand is never mute. But quick in motion as if it caressed Both lady and the lute. Nude as the sunlit air the lady rests. She does not listen with her dainty ear, But trembles at the love song as her breasts Turn pink to hear. She does not rise up at his voice's fall, But takes that music in, By pointed leg and searching hand, with all Her naked skin. Out of that scene, far off, her hot eyes fall, Hoping they will take in The nearing lover, whom she can give all Her naked skin. Paul Engle, “Venus and the Lute Player” Charles I, with his second son, James, Duke of York, in 1647 Painted by Peter Lely [Lilly] (1618–1680). SEE ! what a clouded Majesty ! and eyes Whose glory through their mist doth brighter rise ! See ! what an humble bravery doth shine, And griefe triumphant breaking through each line How it commands the face ! so sweet a scorne Never did happy misery adorne ! So sacred a contempt, that others show To this, (oth' height of all the wheele) below ; That mightiest Monarchs by this shaded booke May coppy out their proudest, richest looke. Whilst the true Eaglet this quick luster spies, And by his Sun's enlightens his owne eyes ; He cares his cares, his burthen feeles, then streight Joyes that so lightly he can beare such weight ; Whilst either eithers passion doth borrow, And both doe grieve the same victorious sorrow. Richard Lovelace, “To my Worthy Friend Mr. Peter Lilly : on that excellent Picture of his Majesty, and the Duke Of Yorke, drawne by him at HamptonCourt.” These, my best Lilly with so bold a spirit And soft a grace, as if thou didst inherit For that time all their greatnesse, and didst draw With those brave eyes your Royal Sitters saw. Not as of old, when a rough hand did speake A strong Aspect, and a faire face, a weake ; When only a black beard cried Villaine, and By Hieroglyphicks we could understand ; When Chrystall typified in a white spot, And the bright Ruby was but one red blot ; Thou dost the things Orientally the same Not only paintst its colour, but its Flame : Thou sorrow canst designe without a teare, And with the Man his very Hope or Feare ; So that th' amazed world shall henceforth finde None but my Lilly ever drew a Minde. William Blake, “The Clod and the Pebble” "Love seeketh not Itself to please, "Nor for itself hath any care, "But for another gives its ease, "And builds a Heaven in Hell's despair." So sang little Clod of Clay Trodden with the cattle's feet But a Pebble of the brook Warbled out these metres meet: "Love seeketh only Self to please, "To bind another to Its delight, "Joys in another's loss of ease, "And builds a Hell in Heaven's despite." William Blake (1757-1827), Songs of Experience Blake illustrated and engraved his own works J. M. W. Turner, British, 1775-1851 Slave Ship (Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhon Coming On). Oil on canvas (35 3/4 x 48 1/4 in.) David Wright“Before You Read the Plaque About Turner's Slave Ship" See the bare canvas. A pure white bone that splits the sky's weak, warm skin of colors. What will be left on the ocean floor, What will be left under the swells, What will be left is unspeakable and vivid and not the vicious beauty of cracking masts against the atmosphere writing lines of blood. Not the blended light, or the curious gulls. Not the market's fanacious hope. Not the gods' desperation to include us in this disaster, without our will. But the bare, bright, smoothed bones of many, many hands, so cold, down where the master could not imagine, could not light the darkest depths. Kitagawa Utamaro, Girl Powdering Her Neck Musee Guimet, Paris. The light is the inside sheen of an oyster shell, Cathy Song, sponged with talc and vapor, “Girl Powdering moisture from a bath. A pair of slippers Her Neck” are placed outside from a ukiyo-e the rice-paper doors. She kneels at a low table print by Utamaro in the room, her legs folded beneath her as she sits on a buckwheat pillow. Her hair is black with hints of red, the color of seaweed spread over rocks. Morning begins the ritual wheel of the body, the application of translucent skins. She practices pleasure: the pressure of three fingertips applying powder. Fingerprints of pollen some other hand will trace. The peach-dyed kimono patterned with maple leaves drifting across the silk, falls from right to left in a diagonal, revealing the nape of her neck and the curve of a shoulder like the slope of a hill set deep in snow in a country of huge white solemn birds. Her face appears in the mirror, a reflection in a winter pond, rising to meet itself. She dips a corner of her sleeve like a brush into water to wipe the mirror; she is about to paint herself. The eyes narrow in a moment of self-scrutiny. The mouth parts as if desiring to disturb the placid plum face; break the symmetry of silence. But the berry-stained lips, stenciled into the mask of beauty, do not speak. Two chrysanthemums touch in the middle of the lake and drift apart. Claude Monet, Water Lilies 1906 (190 Kb); Oil on canvas, 87.6 x 92.7 cm (34 1/2 x 36 1/2 in); The Art Institute of Chicago Robert Hayden, "Monet's Waterlilies" Today as the news from Selma and Saigon poisons the air like fallout, I come again to see the serene, great picture that I love. Here space and time exist in light the eye like the eye of faith believes. The seen, the known dissolve in iridescence, become illusive flesh of light that was not, was, forever is. O light beheld as through refracting tears. Here is the aura of that world each of us has lost. Here is the shadow of its joy. Paul Gauguin, The Loss of Virginity. 1890-91, Oil on canvas 90 x 130 cm (35 x 50 3/4 in), The Chrysler Museum, Norfolk, Virginia Linda Pastan, “In the Realm of Pure Color" after Gauguin's The Loss of Virginity It is our eyes that lose their innocence, ravished by these purples and greens as we gaze at the woman lying there, her ankles pressed together, like Holbein's christ. She is perfectly immobile, as if the fox signifying lust were hardly there, nor the bird settled on her open hand. Even the procession that winds its slow way towards her is simply a curve of darkness in the distance. In this realm of pure color it is the intense blues of the water that matter, the soft shapes of the rocks, more voluptuous than any woman. And she becomes a flat plane of white in the foreground, the tropical color of sand after the sea has receded. Edvard Munch, Girls on the Jetty (c. 1899) Oil on canvas, approximately 53.5 inches x 49.5 inches. Nasjonalgalleriat, Oslo. Derek Mahon, “Girls on the Bridge” Audible trout, Notional midges. Beds, Lamplight and crisp linen wait In the house there for the sedate Limbs and averted heads Of the girls out Grave daughters Of time, you lightly toss Your hair as the long shadows grow And night begins to fall. Although Your laughter calls across The dark waters, Late on the bridge. The dusty road that slopes Past is perhaps the high road south, A symbol of world-wondering youth, Of adolescent hopes And privileges; A ghastly sun Watches in pale dismay. Oh, you may laugh, being as you are Fair sisters of the evening star, But wait-if not today A day will dawn But stops to find The girls content to gaze At the unplumbed, reflective lake, Their plangent conversational quack Expressive of calm days And peace of mind. When the bad dreams You scarcely know will scatter The punctual increment of your lives. The road resumes, and where it curves, A mile from where you chatter, Somebody screams. The girls are dead, The house and pond have gone. Steel bridge and concrete highway gleam And sing in the arctic dark; the scream We started at is grown The serenade Of an insane And monstrous age. We live These days as on a different planet, One without trout or midges on it, Under the arc-lights of A mineral heaven; And we have come, Despite ourselves, to no True notion of our proper work, But wander in the dazzling dark Amid the drifting snow Dreaming of some Lost evening when Our grandmothers, if grand Mothers we had, stood at the edge Of womanhood on a country bridge And gazed at a still pond And knew no pain. Paul Cezanne, L'Estaque (1883-85) Oil on canvas. The Museum of Modern Art, New York City. Allen Ginsberg “Cezanne’s Ports” In the foreground we see time and life swept in a race toward the left hand side of the picture where shore meets shore. But that meeting place isn't represented; it doesn't occur on the canvas. For the other side of the bay is Heaven and Eternity, with a bleak white haze over its mountains. And the immense water of L'Estaque is a go-between for minute rowboats. Henri Matisse, The Red Studio (1911) Oil on canvas, 71“ x 86” The Museum of Modern Art, NYC There is no one here. But the objects: they are real. It is not As if he had stepped out or moved away; There is no other room and no Returning. Your foot or finger would pass Through, as into unreflecting water Red with clay, or into fire. Still, the objects: they are real. It is As if he had stood Still in the bare center of this floor, W.D. Snodgrass, His mind turned in in concentrated fury, “Matisse: The Red Till he sank Like a great beast sinking into sands Studio” Slowly, and did not look up. His own room drank him. What else could generate this Terra cotta raging through the floor and walls, Through chests, chairs, the table and the clock, Till all environments of living are Transformed to energy-Crude, definitive and gay. And so gave birth to objects that are real. How slowly they took shape, his children, here, Grew solid and remain: The crayons; these statues; the clear brandybowl; The ashtray where a girl sleeps, curling among flowers; This flask of tall glass, green, where a vine begins Whose bines circle the other girl brown as a cypress knee. Then, pictures, emerging on the walls: Bathers; a landscape; a still life with a vase; To the left, a golden blonde, lain in magentas with flowers scattering like stars; Opposite, top right, these terra cotta women, living, in their world of living's colors; Between, but yearning toward them, the sailor on his red cafe chair, dark blue, selfabsorbed. These stay, exact, Within the belly of these walls that burn, That must hum like the domed electric web Within which, at the carnival, small cars bump and turn, Toward which, for strength, they reach their iron hands: Like the heavens' walls of flame that the old magi could see; Or those ethereal clouds of energy From which all constellations form, Within whose love they turn. They stand here real and ultimate. But there is no one here. X.J. Kennedy “Nude Descending a Staircase” Toe upon toe, a snowing flesh, A gold of lemon, root and rind, She sifts in sunlight down the stairs With nothing on. Nor on her mind. We spy beneath the banister A constant thresh of thigh on thigh-Her lips imprint the swinging air That parts to let her parts go by. One-woman waterfall, she wears Her slow descent like a long cape And pausing, on the final stair Collects her motions into shape. Marcel Duchamp, Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 (1912) Oil on canvas, 58”x 35”. Philadelphia Museum of Art. Edward Hopper, House by the Railroad (1925) Oil on canvas, 24 inches x 29 inches. Museum of Modern Art, New York City. Edward Hirsch, “Edward Hopper and the House by the Railroad (1925)” Out here in the exact middle of the day, This strange, gawky house has the expression Of someone being stared at, someone holding His breath underwater, hushed and expectant; This house is ashamed of itself, ashamed Of its fantastic mansard rooftop And its pseudo-Gothic porch, ashamed of its shoulders and large, awkward hands. But the man behind the easel is relentless. He is as brutal as sunlight, and believes The house must have done something horrible To the people who once lived here Because now it is so desperately empty, It must have done something to the sky Because the sky, too, is utterly vacant And devoid of meaning. There are no Trees or shrubs anywhere--the house Must have done something against the earth. All that is present is a single pair of tracks Straightening into the distance. No trains pass. Now the stranger returns to this place daily Until the house begins to suspect That the man, too, is desolate, desolate And even ashamed. Soon the house starts To stare frankly at the man. And somehow The empty white canvas slowly takes on The expression of someone who is unnerved, Someone holding his breath underwater. And then one day the man simply disappears. He is a last afternoon shadow moving Across the tracks, making its way Through the vast, darkening fields. This man will paint other abandoned mansions, And faded cafeteria windows, and poorly lettered Storefronts on the edges of small towns. Always they will have this same expression, The utterly naked look of someone Being stared at, someone American and gawky. Someone who is about to be left alone Again, and can no longer stand it. Kate Fagan, “Circa 1927: Realising Belief” This world of geometry and truth outruns my hand in sprawling colour. Awake in constancy and a vaulted sky where sun gives shape to limbs I saw you standing with the jacarandas, siren of a new present as though feeling could not be pacified by numbers and shone replete in things. We are here — only here. Hill, bucket, river that fills and empties in a pool at my feet. Grace Cossington Smith's Trees, 1927, Newcastle Region Art Gallery Charles Henry Demuth (18831935), I Saw the Figure Five in Gold Oil on board, approximately 30 inches x 36 inches. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City. This is actually a painting on a poem. Demuth’s painting is based on W.C. Williiams’ poem William Carlos Williams, “The Great Figure” Among the rain and lights I saw the figure 5 in gold on a red fire truck moving tense unheeded to gong clangs siren howls and wheels rumbling through the dark city Paul Delvaux, The Village of the Mermaids (1942) Oil on panel, 41”x 49” The Art Institute of Chicago. Who is that man in black, walking away from us into the distance? The painter, they say, took a long time finding his vision of the world. The mermaids, if that is what they are under their full-length skirts, sit facing each other all down the street, more of an alley, in front of their gray row houses. They all look the same, like a fair-haired order of nuns, or like prostitutes with chaste, identical faces. How calm they are, with their vacant eyes, their hands in laps that betray nothing. Only one has scales on her dusky dress. It is 1942; it is Europe, and nothing fits. The one familiar figure is the man in black approaching the sea, and he is small and walking away from us. Lisel Mueller, “Paul Delvaux: The Village of the Mermaids Oil on canvas, 1942” Jackson Pollack, Number 1 (1948) Oil on canvas, 68 inches x 104 inches. The Museum of Modern Art, New York City. No name but a number. Trickles and valleys of paint Devise this maze Into a game of Monopoly Without any bank. Into A linoleum on the floor In a dream. Into Murals inside of the mind. No similes here. Nothing But paint. Such purity Taxes the poem that speaks Still of something in a place Or at a time. How to realize his question Let alone his answer? Nancy Sullivan “Number 1 by Jackson Pollock (1948)” Larry Rivers, Washington Crossing the Delaware (1953) Oil on canvas, 7’x 9’. The Museum of Modern Art, NYC Now that our hero has come back to us in his white pants and we know his nose trembling like a flag under fire, we see the calm cold river is supporting our forces, the beautiful history. To be more revolutionary than a nun is our desire, to be secular and intimate as, when sighting a redcoat, you smile and pull the trigger. Anxieties and animosities, flaming and feeding on theoretical considerations and the jealous spiritualities of the abstract the robot? they're smoke, billows above the physical event. They have burned up. See how free we are! as a nation of persons. Dear father of our country, so alive you must have lied incessantly to be immediate, here are your bones crossed on my breast like a rusty flintlock, a pirate's flag, bravely specific and ever so light in the misty glare of a crossing by water in winter to a shore other than that the bridge reaches for. Don't shoot until, the white of freedom glinting on your gun barrel, you see the general fear. Frank O'Hara, “On Seeing Larry Rivers' Washington Crossing the Delaware at the Museum of Modern Art”