Reading

Comprehension

Strategy:

Using

Background

Knowledge

Look for the traces of your own life in

everything you read.

Catherine M. Wishart

Literacy Coach

Copyright © 2009. All rights reserved.

“A story has as

many versions as

it has readers”

(John Steinbeck).

What is Background

Knowledge?

• Do you remember a particular vacation you took that

was especially great?

• Do you remember the last book you read that you really

liked?

• Do you remember a family event that everyone in the

family still talks about?

• Do you remember a special friend from your childhood?

• Do you remember a specific movie that you really

enjoyed?

• All of these events, experiences, memories make up

your own personal background knowledge.

Activating Background

Knowledge

• When reading a text, make a personal

connection:

–

–

–

–

–

That reminds me of when….

That’s how my family….

My friend used to….

I tried to do something like that when I….

I act like that character when I….

• When you make a personal connection to a text,

you are making a text-to-self connection.

• Text-to-self connections make the reading more

real and more important for the reader.

Text-to-Self Connections

“A Child’s Laughter”

One of a kind this cheerful sound

A child’s laughter wherever it’s found

From the giggling of a baby in a playpen

To the laughter of a toddler again and again

A child’s laughter can bring a smile

To one who hasn’t done so in such a long while

I know because that one was me

Until my daughter’s laugh set mine free

A child’s laughter can bring out the best

Of most every man when he’s depressed

Cause his spirit that’s fallen to soar

Until at last he laughs once more

Harry J. Couchon Jr. Poemhunter.com

What Does the Poem Remind You Of?

• Do you remember a time when a child was

laughing – maybe you as a child?

• Do you remember a time when someone was

especially sad, but a child said or did just the

right thing to change his or her mood?

• Do you recall a special child-parent moment that

ended up in laughter?

• Answering any of these questions when thinking

about the poem means you have drawn on your

background knowledge to make the poem more

real.

• Answering any of these questions means you

have made a text-to-self connection.

Accessing Text-to-Text

Connections

• Text-to-text connections involve linking

two or more different texts you have

personally read.

• When making a text-to-text connection,

you find what is similar and familiar in

these texts.

• Finding the similarities makes learning and

understanding easier.

Background Knowledge:

Text-to-Text Connections

“Shopping at the Hospital”

Mom and Dad were very excited – their new son had

finally arrived. Like all parents, they thought Matthew was

perfect. Today, 2 ½ year old Dawn would meet her new

baby brother for the first time. Dawn dressed up in a fancy

new dress to meet her brother. Mom, Dad, and Dawn all

strolled down to the nursery to see Matthew. Dad lifted up

Dawn so she could see all the babies. Mom beamed and

said, “See that baby right here in front of us? That’s your

new baby brother.” Dawn started to pout. She said, “But

Mommy, I don’t want that one with no hair! I want that one

with the pretty curly hair!”

How Do the Poem and Story

Connect?

• Text-to-text connections:

– Both the poem and the story are about laughing and

happiness

– Both the poem and the story are about children and

how they see the world

– Both the poem and the story show how adults react to

children

• If you had read the poem first, you could use

your background knowledge about children’s

laughter and its effects on adults to understand

the story. This connection is a text-to-text

connection.

Text-to-World Connections

• “Books, articles, and stories that make you

think of something beyond your own life

help you create text-to-world connections”

(Zimmermann and Hutchins, 2003, p. 53).

• Text-to-world connections are often the

most difficult to make.

• Text-to-world connections help you learn

about the world from what you read.

Practicing This Strategy

• The short story, “The Puzzle,” is continued

on the next slide.

• Read this portion of the story carefully.

You may also decide to review previous

portions of the story to assure you recall

the highlights of the characters and the

plot.

Making Connections:

“The Puzzle” by Anonymous

Pugh explained.

“I observed that box on a tray outside a second-hand furniture shop. It struck my eye. I took it up. I examined

it. I inquired of the proprietor of the shop in what the puzzle lay. He replied that that was more than he could

tell me. He himself had made several attempts to open the box, and all of them had failed. I purchased it. I

took it home. I have tried, and I have failed. I am aware, Tress, of how you pride yourself upon your ingenuity.

I cannot doubt that, if you try, you will not fail.”

While Pugh was prosing, I was examining the box. It was at least well made. It weighed certainly under two

ounces. I struck it with my knuckles; it sounded hollow. There was no hinge; nothing of any kind to show that

it ever had been opened, or, for the matter of that, that it ever could be opened. The more I examined the

thing, the more it whetted my curiosity. That it could be opened, and in some ingenious manner, I made no

doubt – but how?

The box was not a new one. At a rough guess I should say that it had been a box for a good half century;

there were certain signs of age about it which could not escape the practiced eye. Had it remained unopened

all that time? When opened, what would be found inside? It SOUNDED hollow; probably nothing at all – who

could tell?

It was formed of small pieces of inlaid wood. Several woods had been used; some of them were strange to

me. They were of different colors; it was pretty obvious that they must all of them been hard woods. The

pieces were of various shapes – hexagonal, octagonal, triangular, square, oblong, and even circular. The

process of inlaying them had been beautifully done. So nicely had the parts been joined that the lines of

meeting were difficult to discover with the naked eye; they had been joined solid, so to speak. It was an

excellent example of marquetry. I had been over-hasty in my deprecation; I owed as much to Pugh.

What Connections Do You

Make?

• Reread this portion of “The Puzzle” to

yourself.

• Think about what kind of connections you

make to parts of the story.

• Complete the double-entry journal page.

Choose your own quotes from the story on

which to comment.

• Be prepared to discuss your connections

with this part of the story in class.

Questions to Guide Making

Background Knowledge

Connections

• Does anything here remind me of something that

happened in my life?

• What do I know now about this topic that I didn’t know

before I read this article?

• How are these two texts related?

• How can I use my background knowledge to predict

what may happen next?

• Can I get a movie going that shows how my own life

experiences and this story have connections?

• What does this article tell me about the world? Do I

agree with what the author says, or do I disagree? Why?

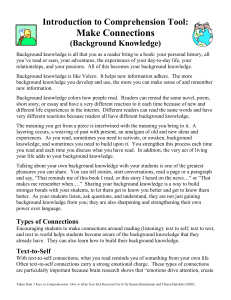

The K-W-L Chart for Non-Fiction

Reading

What I Know

What I Want

to Know

What I

Learned

The K-W-L Chart is a great way to access background knowledge and to track

new learning. When reading about a new topic, brainstorm a list of what you

already know about the topic. Then brainstorm a list of what you believe you

want to learn about the topic. After reading, brainstorm a list of what you learned

that has added to your background knowledge for future reading.

A Simple Way to Build

Background Knowledge

• Spend some time in the children’s section

of the library!

– Important terms will be explained in simple

language

– Important ideas will be presented

– Your background knowledge will be increased

to make reading more difficult texts on the

topic easier to understand

“Remember only this one thing,”

said Badger. “The stories people

tell have a way of taking care of

them. If stories come to you, care

for them. And learn to give them

away where they are needed.

Sometimes a person needs a

story more than food to stay alive.

That is why we put these stories

in each other’s memory. This is

how people care for themselves.

-Crow and Weasel, Barry Lopez

(Zimmermann and Hutchins, 2003, p. 62).

References

• Anonymous. “The Puzzle.”

http://www.classicreader.com/book/1409/1/.

• Couchon, Harry J. Jr. “A Child’s Laughter.”

http://www.poemhunter.com/poems/laughter/.

• “Critical Perspectives: Reading and Writing about

Slavery.”

http://www.readwritethink.org/lessons/lesson_vie

w.asp?id=1060.

• Zimmermann, Susan and Hutchins, Chryse. 7

Keys to Comprehension. NY: Three Rivers Press,

2003.