Public Finance and Public Policy

advertisement

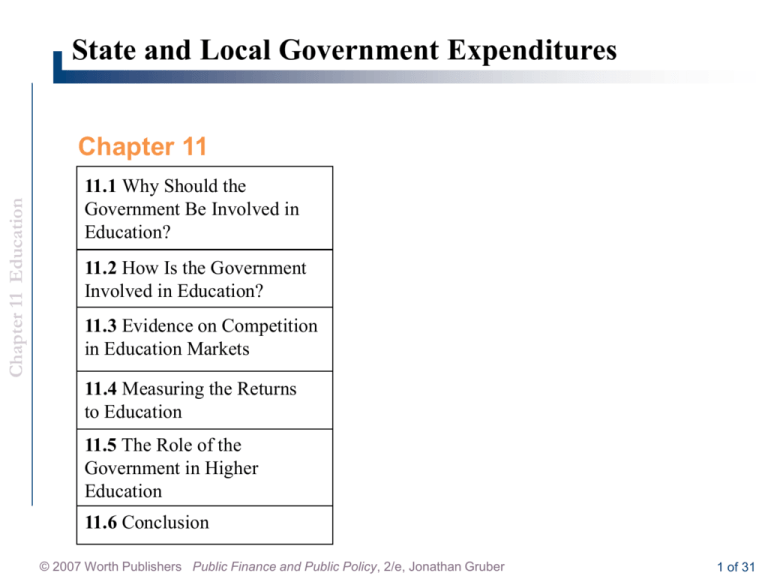

State and Local Government Expenditures Chapter 11 Education Chapter 11 11.1 Why Should the Government Be Involved in Education? 11.2 How Is the Government Involved in Education? 11.3 Evidence on Competition in Education Markets 11.4 Measuring the Returns to Education 11.5 The Role of the Government in Higher Education 11.6 Conclusion © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber 1 of 31 Chapter 11 Education State and Local Government Expenditures © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber 2 of 31 11 . 1 Why Should the Government Be Involved in Education? Chapter 11 Education There are a number of public benefits (positive externalities) to education that might justify a government role in its provision. Productivity The first potential externality from education is productivity. If a higher level of education makes a person a more productive worker, then society can benefit from education in terms of the higher standard of living that comes with increased productivity. Citizenship Education may make citizens more informed and active voters, which will have positive benefits for other citizens through improving the quality of the democratic process. © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber 3 of 31 11 . 1 Why Should the Government Be Involved in Education? Chapter 11 Education Credit Market Failures Another market failure that may justify government intervention is the inability of families to borrow to finance education. In a world without government involvement, families would have to provide the money to buy their children’s education from private schools. educational credit market failure The failure of the credit market to make loans that would raise total social surplus by financing productive education. © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber 4 of 31 11 . 1 Why Should the Government Be Involved in Education? Chapter 11 Education Failure to Maximize Family Utility The reason governments may feel that loans are not a satisfactory solution to credit market failures is that they are concerned that parents would still not choose appropriate levels of education for their children. Redistribution In a privately financed education model, as long as education is a normal good (demand for which rises with income), higher-income families would provide more education for their children than would lower-income families. Income mobility, whereby low-income people have a chance to raise their incomes, has long been a stated goal for most democratic societies, and public education provides a level playing field that promotes income mobility. © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber 5 of 31 11 . 2 How Is the Government Involved in Education? Free Public Education and Crowding Out Chapter 11 Education An important problem with the system of public education provision is that it may crowd out private education provision. © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber 6 of 31 11 . 2 How Is the Government Involved in Education? Chapter 11 Education Solving the Crowd-Out Problem: Vouchers educational vouchers A fixed amount of money given by the government to families with school-age children, who can spend it at any type of school, public or private. © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber 7 of 31 11 . 2 How Is the Government Involved in Education? Chapter 11 Education Solving the Crowd-Out Problem: Vouchers © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber 8 of 31 Chapter 11 Education © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber 11 . 2 How Is the Government Involved in Education? Solving the Crowd-Out Problem: Vouchers Chapter 11 Education Consumer Sovereignty The first argument in favor of vouchers is that vouchers allow individuals to more closely match their educational choices with their tastes. Competition The second argument in favor of vouchers is that they will allow the education market to benefit from the competitive pressures that make private markets function efficiently. © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber 10 of 31 11 . 2 How Is the Government Involved in Education? Problems with Educational Vouchers Chapter 11 Education Vouchers Will Lead to Excessive School Specialization The first argument made here for vouchers, that schools will tailor themselves to meet individual tastes, threatens to undercut the benefits of a common program. By trying to attract particular market segments, schools could give less attention to what are viewed as the central elements of education. © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber 11 of 31 11 . 2 How Is the Government Involved in Education? Problems with Educational Vouchers Chapter 11 Education Vouchers Will Lead to Segregation Critics of voucher systems argue that vouchers have the potential to reintroduce segregation along many dimensions, such as race, income, or child ability. Vouchers Are an Inefficient and Inequitable Use of Public Resources If the current financing were replaced by vouchers, total public-sector costs would rise, since the government would pay a portion of the private school costs that students and their families are currently paying themselves. © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber 12 of 31 11 . 2 How Is the Government Involved in Education? Problems with Educational Vouchers Chapter 11 Education The Education Market May Not Be Competitive The arguments of voucher supporters are based on a perfectly competitive model of the education market. Yet the education market is described more closely by a model of natural monopoly, in which there are efficiency gains to having only one monopoly provider of the good. The Costs of Special Education Each child would be worth a voucher amount that represents the average cost of educating a child in that town in that grade, but all children do not cost the same to educate. special education Programs to educate disabled children. © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber 13 of 31 11 . 3 Evidence on Competition in Education Markets Chapter 11 Education Direct Experience with Vouchers There have been several small-scale voucher programs put in place in the United States in recent years. Probably the most studied program has been the one used in Milwaukee. Studies of this program are reviewed in the Empirical Evidence box. © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber 14 of 31 EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE Chapter 11 Education ESTIMATING THE EFFECTS OF VOUCHER PROGRAMS Rouse (1998) studied the effect of the Milwaukee voucher program on the achievement of students who used their vouchers to finance a move to private schools. • She noted that one cannot directly compare students who do and do not use vouchers, since they may differ along many dimensions. • This selective use of vouchers would bias any comparison between the groups. • Oversubscribed schools had to select randomly from all applicants, using a lottery. In the United States, about 10% of students are enrolled in private schools, a proportion that doubles or triples in the low-income developing world. © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber 15 of 31 11 . 3 Evidence on Competition in Education Markets Experience with Public School Choice Chapter 11 Education Some school districts have not offered vouchers for private schools but have instead allowed students to choose freely among public schools. magnet schools Special public schools set up to attract talented students or students interested in a particular subject or teaching style. charter schools Schools financed with public funds that are not usually under the direct supervision of local school boards or subject to all state regulations for schools. © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber 16 of 31 11 . 3 Evidence on Competition in Education Markets Experience with Public School Incentives Chapter 11 Education Making schools accountable for student performance can provide incentives for schools to increase the quality of the education they offer. Accountability programs can have two unintended effects. • First, they can lead schools and teachers to “teach to the test.” • Second, schools can manipulate the pool of test takers and the conditions under which they take tests to maximize success. © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber 17 of 31 Chapter 11 Education International Evidence Very popular where used Vouchers often rationed Internationally, voucher students perform better Sweden has universal vouchers public schools compete for students © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber 18 of 31 Chapter 11 Education US economic studies, AER June 2007 Simulation of school quality and residential and school choices for Chicago Results enrollment in private schools rise residential choices affected by schools fiscal burden shifted from property tax to income tax private school quality gains religious private schools benefit less © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber 19 of 31 Chapter 11 Education © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber 20 of 31 11 . 3 Evidence on Competition in Education Markets Bottom Line on Vouchers and School Choice Chapter 11 Education There is also little evidence to support the notion that public school choice has major beneficial effects on outcomes. There is some evidence that vouchers improve the academic performance of students who move to private schools, particularly in nations where such systems are widespread. The United States is currently in a phase of experimentation with both choice and accountability that will provide further evidence on the most effective way to improve elementary and secondary education. © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber 21 of 31 11 . 4 Chapter 11 Education Measuring the Returns to Education returns to education The benefits that accrue to society when students get more schooling or when they get schooling from a higher-quality environment. Effects of Education Levels on Productivity There is a large literature that shows that more education leads to higher wages in the labor market. There is substantial controversy, however, over the implications of this correlation. © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber 22 of 31 11 . 4 Measuring the Returns to Education Chapter 11 Education Education as Human Capital Accumulation human capital A person’s stock of skills, which may be increased by further education. Education as a Screening Device screening A model that suggests that education provides only a means of separating high- from low-ability individuals and does not actually improve skills. © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber 23 of 31 11 . 4 Measuring the Returns to Education Education as Human Capital Accumulation Chapter 11 Education Policy Implications Under the human capital model, government would want to support education or at least provide loans to individuals so that they can get more education and raise their productivity. Under the screening model, however, the government would not want to support more education for any given individual. Differentiating the Theories Most of the returns to education reflect accumulation of human capital, although there may be some screening value to obtaining a high school or higher education degree. © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber 24 of 31 EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE Chapter 11 Education ESTIMATING THE RETURN TO EDUCATION AND EVIDENCE FOR SCREENING A simple approach to estimating the return to a year of education in terms of higher wages is to compare people with more education (the treatment group) to people with less education (the control group), but this approach suffers from bias problems. Two methods try to control for this bias in estimating the true human capital effects of education. • The first tries to control directly for underlying ability in a wage regression so that any remaining effect of education represents true productivity effects. • The other approach to control for bias in estimating the human capital returns to education has been quasi-experimental studies that try to find treatment and control groups that are identical except for the amount of schooling they receive. Although all of these approaches have some limitations, the result of the analysis is surprisingly consistent: each year of education raises wages by 7–10%. © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber 25 of 31 11 . 4 Measuring the Returns to Education Effect of Education Levels on Other Outcomes Chapter 11 Education A number of studies have assessed the impact of increased education on external benefits. Key findings include the following: Higher levels of education are associated with an increased likelihood of participation in the political process. Higher levels of education are associated with a lower likelihood of criminal activity. Higher levels of education are associated with improved health of the people who received more education and of their children. Higher levels of education of parents are associated with higher levels of education of their children. Higher levels of education among workers are associated with higher rates of productivity of their coworkers. © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber 26 of 31 11 . 4 Measuring the Returns to Education The Impact of School Quality Chapter 11 Education A number of approaches have been taken to estimate the impact of school quality on student test scores. Findings suggest that the outcomes of efforts to improve school quality can be very dependent on the approach taken to improvements. © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber 27 of 31 EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE ESTIMATING THE EFFECTS OF SCHOOL QUALITY Chapter 11 Education A major focus of research in labor economics is estimating the impact of school quality on student outcomes. Two approaches have been used to address this issue. The first is using experimental data. Example: The state of Tennessee implemented Project STAR in 1985– 1986, randomly assigning 11,000 students (grades K–3) to small classes (13–17 students), regular classes (22–25 students), or regular classes with teacher’s aides. The other approach is a quasi-experimental analysis of changes in school resources. Example: By the mid-1990s, California had the largest class sizes in the nation (29 students per class on average). The California state government in 1996 provided strong financial incentives for schools to reduce their class size to 20 students per class. © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber 28 of 31 11 . 5 The Role of the Government in Higher Education Chapter 11 Education Current Government Role © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber 29 of 31 11 . 5 The Role of the Government in Higher Education Current Government Role Chapter 11 Education State Provision The primary form of government financing of higher education is direct provision of higher education through locally and state-supported colleges and universities. Pell Grants The Pell Grant program is a subsidy to higher education administered by the federal government that provides grants to low-income families to pay for their educational expenditures. © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber 30 of 31 11 . 5 The Role of the Government in Higher Education Current Government Role Chapter 11 Education Loans direct student loans Loans taken directly from the Department of Education. guaranteed student loans Loans taken from private banks for which the banks are guaranteed repayment by the government. For students who qualify on income and asset grounds, the government subsidizes the loan cost to students by (a) Guaranteeing a low interest rate. (b) Allowing students to defer repayment of the loan until they have graduated. © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber 31 of 31 11 . 5 The Role of the Government in Higher Education Current Government Role Chapter 11 Education Tax Relief The final way in which the government finances higher education is through a series of tax breaks for college-goers and their families. The four largest tax breaks add up to about $9 billion per year in forgone government revenue. © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber 32 of 31 11 . 5 The Role of the Government in Higher Education Chapter 11 Education What Is the Market Failure and How Should It Be Addressed? The major motivation for government intervention in higher education is not to produce positive externalities but rather to correct the failure in the credit market for student loans. Given that the major market failure for higher education is in credit markets, shifting state resources away from direct provision and toward loans would likely improve efficiency. © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber 33 of 31 11 . 6 Conclusion Chapter 11 Education The provision of education, an impure public good, is one of the most important governmental functions in the United States and around the world. The optimal amount of government intervention in education markets depends on the extent of market failures in private provision of education and on the public returns to education. © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber 34 of 31 Chapter 11 Education © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber 35 of 31 FY 2008 State of Iowa General Fund Estimated Appropriations Chapter 11 Education (Amounts in millions) Justice System $618.1 Administration & Regulation $257.4 Agriculture & Natural Resources $41.6 Economic Development $96.0 Health and Human Services $1,391.9 Education $3,454.4 Total General Fund Appropriations - $5,859.5 © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber Chapter 11 Education © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber Chapter 11 Education © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber Chapter 11 Education © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber Chapter 11 Education © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber Chapter 11 Education © 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber