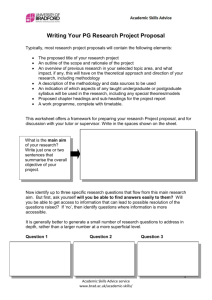

This workshop will - University of Bradford

advertisement

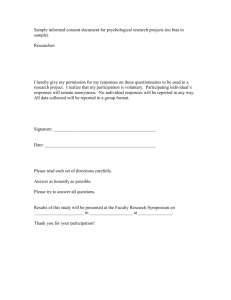

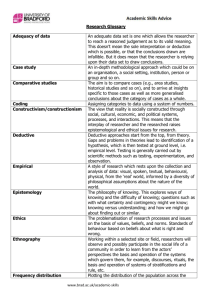

Academic Skills Advice MA and MSc: Research Design This workshop will: - Help you begin to understand the basics of research approaches - Offer hints and tips in getting to grips with quantitative and qualitative methods - Discuss basic ethical considerations that may need to be taken into account - Provide initial tips for those considering secondary, rather than primary, dissertations and projects Teaching points: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. The research design process Philosophies and theories Research approaches Research methods Sampling Bias Ethical considerations Secondary research Reflection 1 www.brad.ac.uk/academic-skills Academic Skills Advice 1. The research design process Research design is a process, including the generation of a plan, with a number of stages all playing their part enabling you to find an answer to your research problem. Your research design involves both the way that you prepare and conduct your research to find the answer to your research question or test your hypothesis. Setting up a Master’s research project includes: Your methodology – the principles that inform the way you make choices and decisions in designing, undertaking and writing up your research Your choice of raw material – documents, data or characteristics for participant selection Your chosen methods – including any conditions you create for undertaking your research Your methods of recording information – at each stage of your research Analytical methods to employ – e.g. statistical approaches, formulae or analytical techniques you apply to your raw data or source materials Data storage and management – the conditions under how you maintain and store your data Conducting the research involves additional thought about: Ethical considerations – e.g. informed consent, confidentiality and anonymity, and many more aspects Bias – from sampling to analysis Although each of these will be discussed separately, many are connected. 2. Philosophies and theories Before we move onto the individual stages above, we will briefly look at two ideas that underpin all research: what exists in the world and how we know about what exists. Ontology and epistemology are terms which make many post-graduate students shudder, but don’t panic. They can be summed up as: Ontology relates to our perception of the world. It is whether we believe the world is knowable and measurable and that everyone shares in the same sense of reality OR the belief that the world is perceived differently by individuals. It is about what we are looking at. 2 www.brad.ac.uk/academic-skills Academic Skills Advice Epistemology explores ways of knowing and the difficulty of knowing. It asks questions, such as do we learn by being ‘told’ passively or do we come to know things through experience? This leads to further questions about how we might go about finding things out. It is about how we look and find out about something/s. These two concepts lead us to understand that nothing is certain, so it is wise not to be over-confident with your research conclusions. Coming to a decision about how we see the world and how we learn will lead you to down one of two paradigm paths. There’s another word post-graduates don’t like – paradigm. It is simply a word that describes the ways we think about and research the world. At one time, the two central paradigms, positivism and interpretivism, were dealt with as separate and competing explanations of how we see the world and learn about it, but philosophers and researchers accept they now happily coexist. Positivists believe that knowledge can be obtained objectively, i.e. what we see and hear is straightforwardly perceived and recordable; that we are able to observe, measure and study the world ‘scientifically’. This means the researcher is ‘distanced’ from the research subject to maintain objectivity. This forms the basis of the scientific methods, among others. Interpretivism reveals the world as a construct we perceive as individuals because we attach different meanings to everything. Therefore, we cannot use the same ‘scientific’ method of measurement, but need to consider people and how they interrelate, by looking at what they say and their behaviour to discover meaning. This means the researcher is ‘closer’ to the participants and may be subjective in their interpretation. So you can see how decisions relating to ontology and epistemology lead to different paradigms being adopted. Let’s sum up what we have covered in the research design process. Ontology: Perception of the world Epistemology: Ways of knowing Paradigm: PositivistStudy world in a detached and objective way Paradigm: InterpretivistStudy world close up and subjectively 3 www.brad.ac.uk/academic-skills Academic Skills Advice This will help you to make a decision about which research approach to take, and therefore which methods and tools to use, i.e. qualitative or quantitative. In short, qualitative methods aim to develop understandings of meanings, and usually work with ‘soft’ data such as words, images, sounds, etc. quantitative methods identify and make sense of patterns in ‘hard’ data in the form of numbers, such as measurements. So, in a very basic way, you could describe quantitative methods as following a positivistic paradigm and qualitative coming from interpretivism. (More on quantitative and qualitative approaches and methods later). Before we finish, a quick word about the ‘ologies’, paradigms, and the two ‘Qs’: they should not be your starting point when deciding on a research question or hypothesis, and it makes sense for them not to be. The focus should be on what you want to find out and the best way to obtain that information, and not the following scenario: ‘I believe we all see the world in the same way and learn through information being provided directly, so I will study from a detached and objective point using a method involving statistical data. Right, what research project could I choose to do that?’ So the model actually looks a bit more like this… Practical top down: What you want to find out and how Research question Methodology/ methods Methodology/ methods Quantitative approach Qualitative approach Paradigm Epistemology Ontology 4 www.brad.ac.uk/academic-skills Philosophical bottom up: The world, knowledge and approaches to research Academic Skills Advice On top of all this, is the use of theory, either to suggest or support your choices for your research project and activity, or to suggest explanations for your findings. It can be difficult for post-graduate students to know how to use theory, with many trying to ‘shoe horn’ it into their assignments and dissertations as they know their tutors/supervisors will expect to see it. A couple of examples of how theory could help are: My research project centred on why some students do not engage with the Academic Skills Advice Service, and their reasons for not using us, so that we can then improve our methods of publicity to raise awareness and hopefully attendance. I have no idea what the outcomes would be but my research of the literature presented some possible explanations of why students do not engage. One of these was a theory of practice by Bourdieu, which suggests people are unable to escape the status they have from birth. This is linked to another theory on how people’s actions are influenced by both the language and behaviour of others. Therefore, one possible reason for students not engaging is because their peers don’t, or their lecturers’ may not have suggested the Service, or they have low expectations of themselves due to their social background. So, theory could help me after my research activity. Alternatively, I could be unsure what research project to undertake within the field of student access and success. If I read Marx’s theory relating to the oppression of the working classes by the elite, this could lead to a research project regarding how Bradford University encourages students from nontraditional backgrounds to consider the institution as an option. So theory could help me before my research activity. Theory Research Question Insert theory here Data collection & analysis OR Findings Theory Insert theory here Above section adapted from Thomas (2013) 3. Research approaches Let’s get back to qualitative and quantitative approaches. To recap, qualitative methods are about interpretation of meaning from people using words, pictures, etc. and quantitative methods find patterns in numerical data. 5 www.brad.ac.uk/academic-skills Academic Skills Advice Activity 1: Q v Q Read the following statements and decide which are advantages or disadvantages for quantitative or qualitative approaches. Each is allocated a letter; please jot down the letter of the statement in the box under the appropriate heading. Quantitative Advantages Disadvantages Qualitative Advantages Disadvantages A. They are useful for in-depth analysis of individual people, businesses, events and occurrences. B. Projects that use quantitative approaches are generally easier to plan and to contain in size, making them ideal for student projects. C. They enable study on a broader scale, such as through online surveys, generating large amounts of data which can be analysed relatively easily using relevant software. D. The results can lack ecological validity (ie that methods, materials and setting must approximate the real-world that is being examined rather than external validity which relates to ability to generalise the research’s findings). E. They can be unpredictable, making them harder to manage and contain. F. They help establish patterns such as trends in behaviour, or in science, ‘universal laws’. G. The research questions or hypotheses tend to be very precisely articulated, allowing the possibility of precise answers. H. They tend to more open-ended, allowing a greater set of responses to emerge. I. Findings may be useful to the particular case but not more generally applicable. J. They have greater ecological validity. K. There is a risk of gaining rather banal results. L. The scale of the research makes it easier to draw reasonably valid generalisations in a relatively short timeframe. M. Not everything is easily measured. There is a risk of gaining skewed understanding of a phenomenon as a result of omitting those aspects that can’t be measured. 6 www.brad.ac.uk/academic-skills Academic Skills Advice 4. Research methods You may already be aware of the many data collection methods available to you as researchers, and you may have researched which could be most useful to you in your project. There are two different types of methods – primary and secondary with the first involving you undertaking empirical research, i.e. direct experience or observation to generate findings. The latter entails using previous research from others to find links, gaps and/or consensus between them to generate something new (Punch 2010). Activity 2: Data collection methods In pairs or small groups, identify appropriate methods of data collection based on the answers within the table above. Use of primary or/and secondary sources Quantitative methods Qualitative methods You do not have to stick to quantitative OR qualitative methods as it is acceptable to mix them to obtain fuller and richer detail. This is called a mixed methods approach. There are some frameworks where it is often expected methods will be combined, such as a case study. Don’t forget to… use the appropriate method to gain the type of data you want ensure it is ‘fit for purpose’, i.e. it is suitable for the intended purpose (questions are clear and understandable, or scales use appropriate measurements) Extract adapted from Dixon and Pearce (2010) 7 www.brad.ac.uk/academic-skills Academic Skills Advice Next, we will look at issues you should concern yourself with depending on whether you are carrying out primary or secondary research. We will start with those relating to primary research. 5. Sampling Whether you chose to undertake quantitative or qualitative research, you will have to make a decision about what or who you will be studying. However, how representative your sample is does depend on which approach you take. For quantitative research, you will want to generalise your results from your (relatively) small sample to a wider population. So, you could say that because research performed on 1000’s of cancer cells reveals feeding them custard inhibits growth, all cancer cells will be similarly affected. Whereas in qualitative research, it is less about broadening results outwards than looking at what individuals say or how they behave, etc., so fewer numbers are required. As you can see, each approach has sample group/s selected differently, and with different numbers of participants required. Remember, that the claims you can make from your data will be very different in each case – avoid making generalisations on the basis of a small, unrepresentative sample (Eve 2008). Another consideration is how you can access whatever makes up your sample: children, silver nitrate, students, false legs, etc. Who would you have to contact, how would you obtain permission, what is the financial cost of access, what are the ethical implications, and many other questions need to be answered and various procedures gone through before you can start. A final word on sampling and samples: if your research project has a qualitative approach, you may come across other terms for ‘sample’. These could include ‘respondent group’ or ‘participatory cohort.’ 6. Bias Bias is anything which stops an impartial and balanced research process from taking place. It can occur at any phase of research, from study design or data collection, to data analysis and publication. As a post-graduate student, you must consider the degree to which you can prevent bias, through proper study design and implementation, or consider how it might influence your study’s conclusions. In extreme cases, bias can cause readers to think one thing when the opposite is true. For example, before 1988, many studies showed that hormone replacement therapy (HRT) decreased the risk of heart disease among women who had gone through the menopause. However, more recent studies, rigorously designed to minimise bias, found the opposite, i.e. an increased risk of heart disease with HRT. (Pannucci and Wilkins 2010) 8 www.brad.ac.uk/academic-skills Academic Skills Advice In quantitative research, the researcher tries to eliminate bias completely: in qualitative research, it is all about understanding what will happen, acknowledging the bias and trying to compensate for it. There are many different ways in which bias can creep into research… Design bias happens when the researcher does not take into account the inherent or fundamental biases found in most experiments, and does not either try to lessen their impact or take them into account when analysing results. For example, ignoring or not compensating for the effect fluctuating Spring temperatures may have on the decomposition of a body. Selection or sampling bias: there are two types– omission and inclusive. In the first, certain groups are omitted from the sample, e.g. ethnic minorities are excluded or only ethnic minorities are studied. Of course, this can be a deliberate decision on the researcher’s part, but you are expected to explain why you have made your sampling choice (see below). The other occurs when samples are selected for convenience, e.g. enlisting students outside a bar for a psychological study. In both cases, the researcher must not generalise their results to a broader population. The following are all forms of data collection bias: Procedural bias: occurs when participants have pressure applied to them to complete their responses quickly, e.g. employees being asked to complete questionnaires during their break time. Measurement bias: arises from an error in data collection and the process of measurement. In quantitative research, this could be that an instrument has not been properly calibrated or set (a faulty scale). Or more generally, any research will have an unavoidable effect on a participant so the researcher must assess the extent to which this happens, such as, respondents providing more socially acceptable answers due to a fear of being judged, which could then skew the results. Interviewer or response bias (sometimes called researcher bias or participant bias): derives from the researcher giving subconscious clues in questionnaire or interview questions to attain the answer they hope for from the subjects. Researchers may make assumptions about how questions or key words will be interpreted or defined. Or the opposite – respondents provide the answers they think researchers want to receive (Shuttleworth 2014). 7. Ethical considerations You will find that many of your ethical considerations are connected, but let’s start with a basic principle: “Ethical practice requires the investigator to respect the individual’s freedom to decline to participate in research.” Faber and Beauchamp (1985: 185) 9 www.brad.ac.uk/academic-skills Academic Skills Advice It may seem odd to start with a statement about people not getting involved with research but it is important to remember that people participate on a voluntary basis. This places the burden on you to ensure they and their rights are respected, and they are provided with all the relevant information about your research project. Whilst obtaining consent is about people agreeing to be involved in a study, informed consent covers a much broader range of associated elements. Participants need to have some detail about the research project and how you intend to collect the data (will you be drawing blood or interviewing them?). They need to know if any harm may come to them whether physical, mental, emotional or even just by making them feel a little uncomfortable. For example… you may want to ask students why they do not attend tutorial sessions they have requested. The answer may be of a personal nature so embarrassment may be caused. Other information to provide participants includes how confidentiality will be maintained; what data storage solutions you have found, how long you will be holding the data for and how you intend to dispose of it; and your contact details. Most importantly, respondents must be made fully aware that they can withdraw or “discontinue participation AT ANY TIME” (my emphasis) (Faber and Beauchamp, 1986: 185). In turn, this may affect the level of anonymity you can employ: if you do not know who has supplied what, how can you withdraw their data? (Thomas 2013). We will look at some of these in more detail starting with anonymity and confidentiality. Many post-graduate students are unsure of the difference between the two, so let’s clear this up. Anonymity refers to concealing the identities of participants in all documents resulting from the research Confidentiality is concerned with who has the right of access to the data provided by the participants Extract adapted from Research Development Initiative (2014) Therefore, you need to consider the ‘level’ of anonymity. In effect, if you will be able to identify participants in the final dissertation and report, you cannot promise anonymity. Regarding confidentiality, it may be that someone will help you to analyse the data (e.g., if there are transcriptions of interviews or focus groups to perform, or many questionnaires to look at) or, as in my case, my colleagues will be reading a report on the findings. Your consent form and participation brief needs to reflect this to ensure participants can make an informed choice about whether or not to take part. 10 www.brad.ac.uk/academic-skills Academic Skills Advice Another aspect already mentioned, and relating to confidentiality, concerns data storage which is relevant to all forms of primary research. Consider where any raw data will be kept, the length of time you keep the raw data and how you intend to dispose of it. Is a locked filing cabinet sufficient to keep hard copies of observations, questionnaires, etc. at work? What if you work from home? Electronic data needs to be appropriately protected by encryption and/or passwords. You must also take into consideration that “personal data processed for any purpose…shall not be kept for longer than is necessary for that purpose” (Information Commissioner’s Office, 2014). Speak to your tutor/supervisor for advice on these and also methods of safely and thoroughly destroying data. It is possible that participants may be misled or not informed in full (i.e. they are victims of ‘deception’) as part of a research project, notably in psychology. However, this is unusual and generally any deception should be avoided as this affects the integrity of informed consent. What to avoid is… Misleading participants about the purpose or procedures of the research Providing incorrect information about the study Leaving information out about the research Observing participants when they do not know they are being watched Extract adapted from Thomas (2015) If you are unsure as to whether your research process could in any way deceive participants, discuss this with your dissertation or project supervisor. If you are asking someone to participate in research, you must consider the relative positions you hold and the influence you may exert over them both to initially be involved as well as during the data collection phase. This is the notion of power and authority. For example… you are a social worker on a lengthy work placement and want to interview regular clients about the other services they use. Even if you don’t, they may perceive that you hold a position of power and that not participating may adversely affect the level of service they receive from you and your colleagues in the future. This perception may also lead them to provide answers they think you want rather than honest replies, so there will be a negative effect on your research. This notion of power and authority can be difficult to negotiate. All participants must be treated with respect and provided with all relevant information but there are some that are particularly vulnerable: obvious categories include children and those with disabilities or mental health issues, but there are others, such as the example above, that also need to be treated with special care and thought. 11 www.brad.ac.uk/academic-skills Academic Skills Advice A quick mention of some of the documents you require if you are studying people: a participation briefing is (usually) written information that provides participants with all the information they need about the research from its aims and intentions to what they need to do and all the above relating to ethics. Your consent form will reiterate this information in such a way that participants can confirm their understanding (e.g. tick boxes at the end of statements) and sign to represent their willingness to be involved. Make sure you follow all the necessary guidelines and requirements of your course and the University as outlined in your handbooks and by your tutor/supervisor. Activity 3: Assessing sampling, bias and ethical considerations Below is an extract from an article: Undergraduate students perceptions of the role and utility of written assessment feedback. (Bailey, 2009) Read the extract and, in pairs or small groups, decide if sampling, bias and ethical considerations are adequately covered in the text. If so, explain how the author has done so; if not, state what is missing and what the author should have included to reveal the appropriate actions had been taken. Space is available overleaf. Abstract: Student dissatisfaction in higher education with written feedback on their assessed work is a topical issue given the publicised findings of the National Student Survey. This paper presents excerpts from interviews with students about their experience with written feedback together with analytical and interpretive commentary. The context of the research was a post-92 university with a wide range of higher education provision and a commitment to widening participation and student retention. The paper begins with an overview of feedback studies in higher education and a summary of current agendas. The data and analysis are presented in three sections. A final discussion section outlines some salient findings from the research. The research comprised semi-structured interviews with student respondents who came from a cross-section of disciplinary areas. Interviews were conducted with individuals and small groups of up to three students. Some students were approached directly through contact with their subject teachers while others were approached through the study skills centres. Participants were traditional and non-traditional (the latter often being mature-age and returnees to education in applied and vocational subject areas). All student participants were undergraduates and some studying one or two year diploma (represented by teaching staff in 12 www.brad.ac.uk/academic-skills Academic Skills Advice those curricular areas as equivalent to at least advanced degree level) courses in nursing and social work. Many of the sample were students following joint degrees or on modularised courses in applied and vocational areas. The departmental and disciplinary background of students is given in parenthesis following each of the data excerpts. Additional information is also included in some instances using square ([ ]) brackets. Questions asked by the interviewer are italicised in the excerpts. Initially the following questions were asked: What do you like/dislike about written feedback? What do find useful/less useful about written feedback? The emphasis was on open and exploratory talk to allow respondents to consider their experience and perceptions more reflectively and in depth. In the course of the interviews reference was made to the form and delivery of feedback. In some cases students were able to produce documentation in the form of structured feedback sheets and assessment guides. In disciplines that usually adopt quantitative research approaches, other ethical considerations come into play. For natural and human sciences, the health and safety of the researcher and others needs to be taken into account. This could relate to potential cross-contamination or infection from handling tissue samples. Within the computing sector, what is the ethical position regarding the use of people’s likenesses in 3D modelling? Whilst consent is normally pre-negotiated, these issues need to be mentioned within your final year project report or dissertation. 13 www.brad.ac.uk/academic-skills Academic Skills Advice For both quantitative and qualitative research, the ethical watchword is honesty: honesty in how you approach the problem or question, and honesty when you report your results. An open and objective attitude is vital when preparing and undertaking research coupled with a lack of ego or fear about changing a hypothesis when the evidence merits it. Also, your results must be accurately reported with no ‘massaging’ to achieve the desired outcome – do not succumb to pressure of time, or your own or others’ expectations and therefore provide untrue results (Fleddermann 1999). So, you have completed your data collection activity but before analysing your data, you need to manage it so it is ready to analyse. Sometimes, your data management drives the format a tool will take, e.g. you intend to undertake a large questionnairebased survey with potentially hundreds of responses. One way to speed up collation and analysis would be to enter your data automatically via a specific software programme. Therefore, you would have to structure your questionnaire in such a way that it can be read by the software. Depending on your research tool, you may have a lot of information that is not relevant to your research question. Therefore, the first thing you need to do is to ‘mine for the gold’. Whether reading through your transcripts or looking at your spreadsheets or databases, relevance is the key (Cohen et al. 2010) Once you have your reduced any relevant information, ask yourself the following analysis questions : a) b) c) d) e) Are there any clear themes? Can you claim any generalisations? Do you have any chunks of data to underpin your interpretations? Are there any quotations or vignettes representing an overarching theme? Is there any patterned data? What does not fit this/these pattern/s? Does that tell you anything? f) How does this/these case study/ies relate to others? g) What gaps or puzzles remain? Extract adapted from Cousin (2009) 8. Secondary research The secondary research methodology involves the summary, collation and synthesis of existing research rather than conducting your own primary research. Existing research could include use of conference papers, reports, censuses, patents, interview transcripts, etc. If this sounds like a literature review, then you are right there are many similarities between them. 14 www.brad.ac.uk/academic-skills Academic Skills Advice One of those is the process of reviewing the literature you will include in your research: Appraisal Quality of literature and findings/outcomes Analysing to identify details Evaluating the literature and how written up Comparison To find patterns or themes Selecting most useful literature Also, you need to employ different reading and note-taking skills at each of the above preliminary phases and for more focused in-depth work. What is different at post-graduate level is the sheer volume of literature you will be using, so it may be useful to update or learn new indexing and cross-referencing methods to help you to keep track of all the documents. Ensuring your notes are organised as you go along will also save time later when you come to the writing stages. Primary and secondary research do have commonalities including many of the elements discussed earlier in the booklet, such as the philosophies and theory/theories underpinning your project; bias in your choice of literature to use in your study and potential bias of the original researchers; and gaining any required permission to use the papers. We run a workshop for taught postgraduate students on appraising and choosing sources; please visit our website for further details. 9. Reflection You may be asked to keep reflective logs or journals during your research process, either as an assignment or as a tool to consider emotions, events and other experiences. These could simply be records of in lab books (scientific procedures) to refer to if you decide to repeat an experiment, or they could be basic descriptive diaries, or they may be full journals. Even if you are not required to do so, it can be a worthwhile exercise and increase the rigour of your research. Reflection is a valuable transferable skill to take into your professional life. It is seen as the method by which a professional grows, changes and adapts – by constantly thinking about the impact of their expertise and predispositions, its strengths and the areas that can be developed further given what they know about theory, method and practice in their field. 15 www.brad.ac.uk/academic-skills Academic Skills Advice The skills associated with stepping back and pausing to look, listen and reflect, are closely related to those concerned with critical thinking which also requires you to ‘unpack’ whatever you are focusing on, not simply accept what you read or hear at face value. Through this process you will probably identify things you would not otherwise notice. The key to reflecting is spotting the patterns and links which emerge as a result of your experiences. Sometimes this is difficult for students because the focus is on you and this might not feel comfortable – especially when you are usually encouraged to depersonalise your work in essays and reports. Remember, you try to avoid saying ‘I’ in essays? So, when writing reflectively, you need to find a way to be both academic and personal, and that is not always easy. You may be both referencing academic theory and, in the same piece of writing, describing an exciting learning experience you had during a tutorial. Becoming reflective is, in part, about feeling comfortable with this dual process – to do this takes practice (Learning Development 2010). It can help you to be reflective about your research process whilst you do it, rather than making notes and then reflecting at the end of your project. For example, when starting your review of the literature, you should keep notes and records on what key search terms you have used, what articles may be of interest and why. You can then reflect on how you have selected and critically analysed these sources to be more efficient and effective in the future by identifying what skills you need to improve on, whether you have a broad enough variety of sources, etc. Your Subject Librarian will be able to help you with most issues relating to accessing texts of all sorts, and there are many hard copy and internet sources available on research and planning (Charlesworth 2015). References Bailey, R. (2009) Undergraduate students perceptions of the role and utility of written assessment feedback. Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. http://www.aldinhe.ac.uk/ojs/index.php?journal=jldhe&page=article&op=view&path %5B%5D=29&path%5B%5D=26 Accessed 9 January 2015. California State University. (2014) Use of deception in research. Hayward: California State University. http://www20.csueastbay.edu/orsp/forms-policies-procedures/irb/deception.html Accessed 4 December 2014. Charlesworth, A. (2015) Doing research: planning, risk and reflection. Bristol: University of Bristol. https://www.cs.bris.ac.uk/Teaching/learning/how-to-lectures/planning-riskreflection.pdf Accessed 7 January 2015. Cohen, L., Manion, L., and Morrison, K. (2010) Research methods in education. 6th ed. Abingdon: Routledge. 16 www.brad.ac.uk/academic-skills Academic Skills Advice Cousin, G. (2009) Researching learning in Higher Education. Abingdon: Routledge. Dixon, N. and Pearce, M. (2010) Guide to ensuring data quality in clinical audits. London: Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership. http://www.hqip.org.uk/assets/LQIT-uploads/Guide-to-ensuring-data-quality-inclinical-audits-8-Sep-10.pdf Accessed 7 January 2015. Eve, J. (2008) Writing a research proposal: planning and communicating your research ideas effectively. Brighton: University of Brighton. http://about.brighton.ac.uk/ask/files/6813/7206/9880/Writing_a_Research_Proposal. pdf Accessed 7 January 2015. Faben, R and Beauchamp, T. (1986) A history and theory of informed consent. New York: OUP. Fleddermann, C. (1999) Engineering ethics. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall Inc. Information Commissioner’s Office. (2014) Data protection principals. Wilmslow: Information Commissioner’s Office. https://ico.org.uk/for_organisations/data_protection/the_guide/the_principles Accessed 4 December 2014. Learning Development. (2010). Reflection. Plymouth: Plymouth University. http://www.plymouth.ac.uk/uploads/production/document/path/1/1717/Reflection.p df Accessed 7 January 2015. Pannucci, C. and Wilkins, E. (2010) Identifying and avoiding bias in research. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 126 (2) 619-625. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2917255/ Accessed 7 January 2015. Punch, K. (2010) Developing effective research proposals. 2nd ed. London: Sage Publications Ltd. Research Development Initiative. (2014) Anonymity and confidentiality. Lancaster: Lancaster University. http://www.lancaster.ac.uk/researchethics/1-2-anonconf.html Accessed 4 December 2014. Shuttleworth, M. (2014). Research bias. : Explorable.com. https://explorable.com/research-bias Accessed 7 January 2015. Thomas, G. (2013) How to do Your research project. London: Sage Publications Ltd. Thomas, S. (2015) Deception: definition, meaning and quiz. Mountain View: Education Portal. http://education-portal.com/academy/lesson/deception-definitionmeaning-quiz.html#lesson Accessed 21 January 2015. 17 www.brad.ac.uk/academic-skills Academic Skills Advice Answers Activity 1: Q v Q Quantitative Advantages Disadvantages B,C,F,G,L D,K,M Qualitative Advantages Disadvantages A,H,J E,I Activity 2: Data collection methods Use of primary or/and secondary sources Primary Primary Primary Primary Secondary Primary Secondary Primary Quantitative methods Qualitative methods Structured detachedobserver non-participant involved observation Questionnaire: structured closed questions Experiment Structured interview closed questions Use of statistical data Involved observer and participant observation (ethnography) Questionnaire: less-structured open questions Less-structured interview openquestions Focus group Use of reports Close measurement Activity 3: Assessing sampling, bias and ethical considerations Informed consent – no mention of this in the extract so do not know if information about the research was given to students. Also, no mention of participation briefing and consent forms being understood and completed. Anonymity – again, no discussion about the level of this especially as have used tutors and student support centre to find students. Confidentiality – do tutors and support staff have access as helped to source students, and as the results could be of interest to the former. Deception – n/a although not properly explaining what the research is about could be deemed so. Power and authority – we have no information on who the researcher is so we cannot access the relationship. Location is also undisclosed which can affect the power dynamic. 18 www.brad.ac.uk/academic-skills