Measuring Stress

advertisement

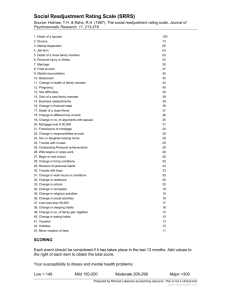

Measuring Stress Health Psychology Reasons 1. 2. Clinical diagnosis Research Three different types of measurement 1. 2. 3. Physiological Psychological Behavioural Physiological One way to assess arousal is to use electrical/mechanical equipment to take measurements of blood pressure, heart rate, respiration rate, or galvanic skin response (G. S. R.). The Polygraph measures all of these simultaneously. Miniature Polygraphs can be carried around. Researchers using a miniature Polygraph were able to find that ambulance workers had higher blood pressure whilst at work compared with when they were at home (Goldstein et al. 1992). However, being wired to a polygraph could increase stress. Polygraph test Blood or urine samples Blood or urine samples can be assessed for the level of hormones that the adrenal glands secrete. There are two main classes of hormones: corticosteroids (for example cortisol) and catecholamines (for example, adrenaline and noradrenaline. Measurements need to be analysed by a chemist using special procedures and equipment. However, having blood taken could cause stress. Evaluation There are several advantages to using measures of physiological arousal to assess stress. Physiological measures are reasonably direct and objective, quite reliable, and easily quantified. The disadvantages are that the techniques are expensive, the technique is stressful for some people and the measures are affected by factors such as gender, weight, activity prior to measurement and such substances as caffeine. Psychological stress does not always produce physiological arousal. Psychological Life events Holmes and Rahe (1967) Psychological The most widely used scale of life events has been the 'social readjustment rating scale (SRRS.)' developed by Holmes and Rahe (1967). The scale was made by constructing a list of events that were derived from clinical experience. Hundreds of men and women of various ages and backgrounds rated the amount of readjustment needed by people experiencing each of the stressful events. They were asked to give the average degree of readjustment. Holmes and Rahe (1967) To measure the amount of stress people have experienced subjects check off each life event they have experienced during the past 24 months. The values of the check items are then totalled to give the stress score. Holmes and Rahe (1967) Death of spouse 100 Divorce 73 Separation 65 Jail term 63 Death of close family member 63 Personal illness or injury 53 Marriage 50 Fired at work 47 Marital reconciliation 45 Retirement 45 Holmes and Rahe (1967) Change in health of family member 44 Pregnancy 40 Sex difficulties 39 Gain of new family member 39 Business readjustment 38 Change in financial state 38 Death of close friend 37 Change to a different line of work 36 Change in number of arguments with spouse 35 Holmes and Rahe (1967) Foreclosure of mortgage or loan 30 Change in responsibilities at work 29 Son or daughter leaving home 29 Trouble with in-laws 29 Outstanding personal achievement 28 Spouse begins or stops work 26 Begin or end of school or college 26 Change in living conditions 25 Change in personal habits 24 Trouble with boss 23 Holmes and Rahe (1967) Change in work hours or conditions 20 Change in residence 20 Change in school or college 20 Change in recreation 19 Change in church activities 19 Change in social activities 18 A moderate loan or mortgage 17 Change in sleeping habits 16 Change in number of family get-togethers 15 Change in eating habits 15 Holmes and Rahe (1967) Holiday 13 Christmas 12 Minor violations of law 11 Holmes and Rahe (1967) A survey of nearly two thousand eight hundred adults who filled in a version of the SRRS found that 15% experienced none of the events during the prior year, and 18% reported five or more. The three most frequent events were "took a vacation" (43%), "the death of a loved one or other important person" (22%), and "illness or injury" (21%). Holmes and Rahe (1967) The older the person the fewer life events reported and the more educated the person more life events were reported. Single, separated, and divorced people reported a larger number of events compared with married and widowed individuals (Goldberg & Comstock, 1980). Problems with the scale Major life events are rare therefore low scores Some items are ambiguous. Items in the SRRS are vague or ambiguous (Hough et al, 1976). For example, "change in responsibilities at work" does not take into account how much change or whether there is more or less responsibility. "Personal injury or illness" does not take into account the seriousness of the illness. This reduces the precision of the instrument. Problems with the scale Value of items vary depending on what group the respondent belongs to. Large individual differences in ability to cope Large cultural differences in our experience of events. Value of events change over time. So text loses its validity. Problems with the scale A weakness of the SRRS is that there is a poor correlation (about .30) between the score and illness (Dohrenwend & Dohrenwend, 1981). One reason could be that there are other many possible reasons for why people get sick and have accidents. Problems with the scale The scale does not consider the meaning or impact of an event for the individual (Cohen et al, 1983). For example, two people who each had a mortgage for 20,000 dollars would get the same score for "mortgage over 10,000 dollars" even though one of them made ten times the income of the other. The amount of stress caused by the "death of spouse" could depend upon the age, dependence on the spouse, and the length and happiness of the marriage. This again reduces the precision of the instrument. Problems with the scale The scale does not distinguish between desirable and undesirable events. "Marriage" or "outstanding personal achievement" are often viewed as desirable; but "sex difficulties" and "jail term" are obviously seen as undesirable. Some items can be viewed either way, for example, "change in financial state"; the score is the same regardless of whether the finances improve or worsen. Studies have found that undesirable life events are correlated with illness, but desirable events are not (McFarlane et al, 1983). Evaluation High correlation between men and women, Catholics and Protestants. Not so high for Black Vs White. The SRRS has face validity because many of the events listed are easily recognisable as stressful events. The values Allocated to each stress event have been carefully calculated from data provided by the opinions of many people. The survey form can be filled out easily and quickly. Daily hassles Kanner et al (1981) - minor stressors and pleasures of everyday life might have a more significant effect on health than the big events. - Takes account of the cumulative nature of stress. Daily hassles Richard Lazarus and his associates designed this scale. It concentrates on recent stressors, the annoying things that happened to everybody everyday. The hassles are rated as having been "somewhat," "moderately," or "extremely" severe. Daily Hassles 100 middle-aged adults were tested monthly over a nine-month period. The 10 most frequent hassles reported were: Concerns about weight Health of a family member Rising prices of common goods Home maintenance Too many things to do Misplacing or losing things. Outside home maintenance Daily Hassles Property, investment or taxes Crime Physical appearance Uplifts scale In addition to the hassles scale there is another instrument, the uplifts scale, which measures the good events in life. It is reasonable to assume that experiencing events that bring peace, satisfaction, or joy would allow people to endure the hassles of daily life. Uplifts experienced in the past month are recorded on a three-point scale. Uplifts scale The uplifts are rated as having been "somewhat," "moderately," or "extremely" strong. The 10 most frequent uplifts reported were: Relating well to spouse or lover Relating well with friends Completing a task Feeling healthy Getting enough Sleep Eating out Uplifts scale Meeting your responsibilities Visiting, phoning or writing to someone Spending time with the family Home pleasing to you Hassles, Uplifts and Life events One study tested middle-aged adults, using 4 instruments: The hassles scale The uplifts scale A life events scale that includes no desirable items The health status Questionnaire, containing questions about general health (Delongis et al., 1982). Hassles, Uplifts and Life events There is a weak correlation between hassles scores and health status, as well as between life event scores and health status. Hassles were more strongly associated with health than life events. There was no association found between uplifts scores and health status for men, but there was for women. Test - re-test reliability Self-report measures of life events are unreliable. A study had subjects fill out a scale regarding life events they experienced during the prior year. The subjects then filled out the same Questionnaire every month for a year. Towards the end of the year the reports were quite different from the ones made at the beginning of the year (Raphael, et al. 1991). Other methods of measuring stress Above methods only provide a snapshot. Stress varies from day to day. Gulian et al (1990) - study of British drivers. Completed psychometric tests (e.g. Rotter's Internal - External Locus of Control Scale). Also filled in a diary of their feelings while driving over 5 days. Results More stress in the evening and midweek. Stress varied with age and experience, health condition, sleep quality, driving conditions, driver's perception of driving as stressful. Douglas et al (1988) Douglas et al (1988) used diary and physiological measures 100 fire fighters from 12 stations. Heart rate recorded for minimum of 48 hours (used portable electrocardiogram) Douglas et al (1988) Results yielded a 'Ventricular cardiac strain score'. High scores were found to correspond with number of call-outs, level of seniority, and stressful events recorded in diaries. The end