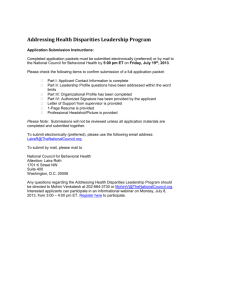

Manual for Addressing Health Disparities

advertisement