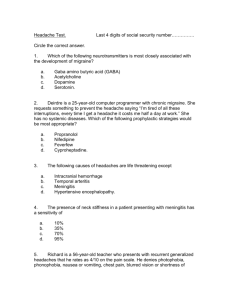

Headaches

advertisement

Headaches Differentiating the benign from the serious By Dr. Cuong Ngo-Minh Back to Basics April 16th 2009 Objectives LMCC • Differentiate benign vs serious headache via symptoms and signs, investigation • Pathophysiology of migraine and pain sensation of other cause of headache • Identify patients requiring brain imaging • Conduct effective plan of management on acute vs chronic setting, appropriate use of medication • Appreciate impact of misdiagnosis and mistreatment (CLEO) Etiology of headache disorders 1 Primary • Migraine (pulsatile, 2-72 hours, incapaciating photo-phono-phobia,): - Migraine without aura (common migraine) - Migraine with aura (classic migraine) • Cluster Headache (recurrent severe periorbital attacks) • Tension-type headache (eg posterior neck muscle contraction) The Medical Council of Canada (2005) Etiology of headache disorders 2 Secondary • H/a assoc. with vascular disorders: – – – – – Subarachnoid hemorrhage (Emergency!) Temporal arteritis (risk of blindness) Venous thrombosis Intracranial hematoma (including epidural, subdural) Severe arterial hypertension • H/a assoc. with nonvascular intracranial disorders: – Infection (meningitis, abscess, sinusitis) – ↑ CSF pressure (intracranial mass lesion or hydrocephalus) • Miscellaneous: – Medication: side effect nitroglycerin or withdrawal (analgesics) – Psychological disorders The Medical Council of Canada (2005) History for headache : • Onset (Acute vs slowly progressive) , frequency, duration (hours,days?) , quality, intensity (worse ever?) , location, triggers (worse with exertion?, food? menstruation?) and ameliorating factors, assoc sx (pulsatility, photo-phonophobia) Functional impairment (work, IADLs) • Red flags (neuro symptoms, severity of disability) for serious disease to differentiate between the causes of h/a. • Select patients in need of immediate management based on red flags on history and physical signs Clinical,diagnostic imaging, laboratory findings 1 • Vitals, Level of conscioussness, Head and neck, Neurological exam, (especially visual, motor, reflex, sensory, speech or cognitive), if + finding investigation is warranted. • Identify patients that require referral/brain imaging 1) new/explosive onset, 2) change in pattern, 3) jaw claudication, 4) limb girdle pain, 5) worse with stooping over, straining, coughing; 6) neurological signs on exam 7) temporal artery tenderness. • X-rays and other tests may also be used if sinusitis is suspected Gray J, Therapeutic Choices (2007) Red flags for serious headache Age of onset Middle-aged to elderly pt Type of onset Severe and abrupt Temporal sequence Progressive severity or increased frequency Pattern Significant change in h/a pattern. Neuro signs Stiff neck, focal signs, Reduced consciousness Systemic signs Fever, appears sick, abnormal examination Gray J, Therapeutic Choices (2007) Migraine headache • Unilateral in more than 50 % pts, Pulsating or throbbing in 50 % • Bilateral more common than previously thought. • Migraine can begin on one side then switch to other side. • Headache phase usually lasts between 2 and 72 hrs. • Invariably associated w~ other sx: nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. • Heightened sensory perceptions such as photophobia, phonophobia, & increased sensitivity to smell occur during attacks. • More common in individuals w/ family hx. More in women (women w/ mother w/ migraine) Prevalence: 19% of women in gen. pop • Common triggers: certain foods (aged cheese, chocolate), alcohol menstruation, stress, worry, lack of sleep, fatigue. Migraine without aura (common migraine) • Typically episodic • Prodromal phase: Sx of excitation or inhibition of CNS, i.e., elation, irritability, excitability, increased appetite or craving for certain foods, especially sweets; depression, sleepiness, and fatigue. Occurs in 30% of pts. • Prodrome sx may precede migraine attack by up to 24 hrs. • Aura: Migraine with aura 1 – Definition: focal neurological phenomena that precede or accompany the attack. – Appear over 5 to 20 minutes. Last ≤ than 60 minutes. – 20–30% of clients suffering from migraine Chronology of headache phase from end of aura (3 patterns): a) within 60 minutes b) delayed up to several hours c) No headache Young, William B. and Silberstein, Stephen D., Migraine and Other Headaches. St. Paul, Minn: AAN Press, 2004.; Evans, Randolph W., MD, and Matthew, Ninan T., MD. Handbook of Headache, Second Edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2005 ; Silberstein, Stephen D.; Lipton, Richard B.; Goadsby, Peter J. Headache in Clinical Practice Second Edition. Andover: Thomson Publishing Services. 2002. • Aura: Migraine with aura 2 – Visual, sensory, or motor in nature. – Visual aura is the most common. Subtypes – a) photopsia: unformed FLASHES of white and/or black or rarely of multicolored lights – b) scintillating scotoma: dazzling zigzag lines (if arranged like a castle = "fortification spectra" or "teichopsia"). Some patients complain, tunnel vision and hemianopsia. – Auditory or olfactory hallucinations, – SomatoSENSORY: paresthesias, eg. pins-and-needles can migrate up the arm → face, lips and tongue (ipsilateral). Or temporary dysphasia, vertigo and hypersensitivity to touch. Ddx TIA Clinical,diagnostic imaging, laboratory findings 2 • Lumbar puncture if subarachnoid hemorrhage, encephalitis, high- or low-pressure headache symptoms or meningitis is suspected. • Laboratory tests (on an individual basis) – ESR for suspected temporal arteritis – Endocrine, biochemical, infection work-up – Search for malignancy if indicated • Facial pain may need a thorough assessment by a dental specialist familiar with headaches and facial pain and/or an ENT specialist if sinus or other ENT disorders are suspected. Gray J, Therapeutic Choices (2007) Key elements in Hx and PE for h/a Diagnosis Question/Maneuver Assist in narrowing differential dx, comparing previous presentations Previous hx of h/a, types, freq, tx Serious underlying pathology Look for red flags Migraine Hx of throbbing, photophobia, assoc nausea, unilateral pattern, pos family hx, hx of aura Analgesic rebound h/a Hx of med use (types, freq, qty) Assist in planning tx and screen for depression, chronicity of hx, likelihood of compliance, and motivation for recovery Psychosocial hx: previous hx of anxiety/depression; substance abuse; current life stresses; activity/exercise level; patient’s worries about the h/a Serious underlying pathology Screening neuro exam TMJ, sinusitis, cervical arthritis, or temporal arteritis Palpate head, neck, and scalp Sloane, PD et al. -The Essentials of Family Medicine (2002) Diagnosis & Initial Assessment of Headache Headache Abrupt Recurrent Severe or new onset Typical pattern with mild to moderate pain Immediate assessment Elective assessment Rule out SAH and meningitis Usually benign primary h/a disorder Migraine Symptomatic or prophylactic tx. Tension-type Symptomatic or prophylactic tx. Gray J, Therapeutic Choices (2007) Progressive Accompanied by neurologic symptoms and signs Assess as soon as possible Possible mass lesion Other Symptomatic or prophylactic tx. Treatments for benign headache syndrome 1 • Symptomatic tx – Analgesics • Ibuprophen, naproxen, and ASA or acetaminophen with or without codeine and/or butalbital, are used for mild to moderate h/a pain. • Non-opioid meds should be used less than 15 days per month (re: prevent REBOUND h/a) • Butalbital compounds, Tylenol #3 and other opioids have limited use, should be used less than 10 days per month, in benign h/a disorders b/o the potential for addiction. • Medication over-use h/a can result from overuse of analgesics/ rebound/ dependency, which limits their longterm potential. Gray J, Therapeutic Choices (2007) Treatments for benign headache syndrome 2 • Symptomatic tx. – Ergot derivatives • Ergotamine acts on serotonin receptors and is classically used for migraines and cluster h/a but use is limited by side effects. They may cause rebound h/a if used 10 days per month or more. – Triptans • They act on the serotonin (HT-5) subclass 1B and 1D receptor, on extracerebral blood vessels and neurons, and the mechanism of action is prevention of neurologically sterile inflammatory responses around vessels and vasoconstriction. • They are contraindicated in patients with cardiac disorders, sustained hypertension, basilar and hemiplegic migraine. Gray J, Therapeutic Choices (2007) Treatments for benign headache syndrome 3 • Symptomatic tx. – Other classes of drugs • Corticosteroids can be useful in many h/a disorders, including status migraine, cluster h/a, and cerebral neoplasms with edema (especially metastatic lesions, temporal arteritis). • Other drugs include metoclopramide (maxeran) phenothiazines, Ketorolac, meperidine, indomethacin, dimenhydrinate and domperidone. Gray J, Therapeutic Choices (2007) Treatments for benign headache syndrome 4 • Symptomatic tx. Prophylactic tx. Is indicated if the migraine attacks are severe enough to interfere with the patient’s quality of life, or if the patient has three or more severe per month that fail to respond adequately to symptomatic tx. – – – – – Beta-blockers Calcium channel blockers Tricyclic antidepressants Anti-epileptic drugs (Valproic acid, topirimate, gabapentin) Serotonin agonists (methysergide) Gray J, Therapeutic Choices (2007) Patient education and counseling for management of benign headache syndrome • A calendar or diary of h/a is useful f/u assessment • A record of medications (usefulness, dosage, side effects) should be kept. • Reassurance and explanation are most important to the patient in the long term. • Always offer hope to the patient with chronic h/a even if no cure is available; most primary h/a can be controlled • For tension ha, attempt to modify or eliminate the stressor with behaviour modification, biofeedback, relaxation therapy, yoga, exercise, and so on. Gray J, Therapeutic Choices (2007) Physicians’ legal liability for negligence (CLEO 5.4) • Physicians are legally liable to their patients for causing harm through a failure to meet the standard of care that is applicable under the particular circumstances under consideration. • In a patient with headache, the primary care physician may miss a serious headache, such as subarachnoid hemorrhage. The diagnosis is missed most often because of incomplete clinical assessment. Although serious causes for headache are not frequent, failure to diagnose has potentially disastrous consequences. Legal liability may result. Applied scientific principles 1 • Intracranial structures that are pain-sensitive: – Dura, tributary veins, venous sinuses, meningeal vessels, tentorium – carotid, vertebrobasilar, cerebellar, and cerebral arteries • Pathophysiology of migraine – Platelet aggregation occurs in CNS – Release of serotonin from the synapses – Increase & decrease in the levels of blood-brain catecholamines, norepinephrine and epinephrine – Origin of aura • ↓blood flow changes → ↓ brain activity of cerebral cortex (referred to as spreading depression) → • ↑ inflammation of trigeminal nerves → • ↑ pain in the meninges. Applied scientific principles 2 – Trigeminoneurovascular system • Afferent trigeminal neurons transmit pain sensation → • back to the central nervous system → ↑ efferent parasympathic pathway (via facial nerve also pterygopalatine and otic ganglia) → ↑ Release vasoactive peptides (eg.VIP vasoactive intestinal peptide) ↑ vasodilation pericranial vasculature Moskowitz MA. The neurobiology of vascular head pain. AnnNeurol 1985;16:157-68. Source of information • Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of migraine in clinical practice CMAJ 1997;156(9): 1273-87 • Merck manual • Therapeutic choices 5th edition 169-187