Social Psychology - Napa Valley College

advertisement

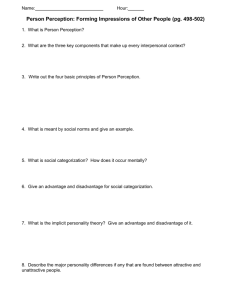

6th edition Social Psychology Elliot Aronson University of California, Santa Cruz Timothy D. Wilson University of Virginia Robin M. Akert Wellesley College slides by Travis Langley Henderson State University Chapter 4 Social Perception: How We Come to Understand Other People “Things are seldom as they seem. Skim milk masquerades as cream.” – W. S. Gilbert Other people are not easy to figure out. Why are they the way they are? Why do they do what they do? We all have a fundamental fascination with explaining other people’s behavior, but all we have to go on is observable behavior: – – – – – What people do What they say Facial expressions Gestures Tone of voice We can’t know, truly and completely, who they are and what they mean. Instead, we rely on our impressions and personal theories, putting them together as well as we can, hoping they will lead to reasonably accurate and useful conclusions. Source of image: Microsoft Office Online. Social Perception Social Perception The study of how we form impressions of and make inferences about other people. Source of image: Microsoft Office Online. Nonverbal Behavior • What do we know about people when we first meet them? • We know what we can see and hear, and even though we know we should not judge a book by its cover, this kind of easily observable information is crucial to our first impression. • With no words at all, we can communicate volumes. Source of image: Microsoft Office Online. Nonverbal Behavior Nonverbal Communication The way in which people communicate, intentionally or unintentionally, without words. Nonverbal cues include: • facial expressions • body position/movement • tone of voice • the use of touch • gestures • gaze Nonverbal Behavior • We have a special kind of brain cell called mirror neurons. • These neurons respond when we perform an action and when we see someone else perform the same action. • Mirror neurons appear to be the basis of our ability to feel empathy. • For example, when we see someone crying, these mirror neurons fire automatically and involuntarily, just as if we were crying ourselves. Source of image: Microsoft Office Online. Nonverbal Behavior Nonverbal cues serve many functions in communication. • You can express “I’m angry” by narrowing your eyes, lowering your eyebrows, and setting your mouth in a thin, straight line. • You can convey the attitude “I like you” with smiles and extended eye contact. • And you communicate your personality traits, like being an extrovert, with broad gestures and frequent changes in voice pitch and inflection. Nonverbal Behavior Some nonverbal cues actually contradict the spoken words. • Communicating sarcasm is the classic example of verbal-nonverbal contradiction. • Think about how you’d say “I’m so happy for you” sarcastically. Facial Expressions of Emotion Are facial expressions of emotion universal? The answer is yes, for the six major emotional expressions: anger, happiness, surprise, fear, disgust, and sadness. All humans encode or express these emotions in the same way, and all humans can decode or interpret them with equal accuracy. Source of images: Microsoft Office Online. Facial Expressions of Emotion • Paul Ekman and others have conducted numerous studies indicating that the ability to interpret at least the six major emotions is cross-cultural—part of being human and not a product of people’s cultural experience. Source of images: Microsoft Office Online. Facial Expressions of Emotion • Other emotions such as guilt, shame, embarrassment, and pride occur later in human development and show less universality. • These latter emotions are closely tied to social interaction. Source of images: Microsoft Office Online. Facial Expressions of Emotion Decoding facial expressions accurately is more complicated than we have indicated, for three reasons. 1. Affect blends occur when one part of the face registers one emotion and another part, a different emotion. 2. At times people try to appear less emotional than they are so that no one will know how they really feel. 3. A third reason why decoding facial expressions can be inaccurate has to do with culture. Culture and the Channels of Nonverbal Communication Display rules are particular to each culture and dictate what kinds of emotional expressions people are supposed to show. Source of images: Microsoft Office Online. Culture and the Channels of Nonverbal Communication Examples of display rule differences: • American cultural norms discourage emotional displays in men, such as grief or crying, but allow the facial display of such emotions in women. • Japanese women will often hide a wide smile behind their hands, whereas Western women are allowed—indeed, encouraged—to smile broadly and often. • Japanese norms lead people to cover up negative facial expressions with smiles and laughter and to display fewer facial expressions in general than is true in the West. Source of image: Microsoft Office Online. Culture and the Channels of Nonverbal Communication • Members of American culture become suspicious when a person doesn’t “look them in the eye” while speaking, and they find talking to someone who is wearing dark sunglasses quite disconcerting. • Cultures vary greatly in what is considered normative use of personal space. Most Americans like to have a bubble of open space, a few feet in radius, surrounding them; in comparison, in some other cultures, strangers think nothing of standing right next to each other, to the point of touching. Culture and the Channels of Nonverbal Communication Emblems Nonverbal gestures that have well-understood definitions within a given culture; they usually have direct verbal translations, like the “OK” sign. The important point about emblems is that they are not universal. Each culture has devised its own emblems, and these need not be understandable to people from other cultures. President George H. W. Bush once used the “V for victory” sign, but he did it backward—the palm of his hand was facing him instead of the audience. Unfortunately, he flashed this gesture to a large crowd in Australia—and in Australia, this emblem is the equivalent of “flipping the bird”! Source of image: Microsoft Office Online. Multichannel Nonverbal Communication • Because nonverbal information is diffused across these many channels, we can often rely on one channel to understand what is going on. • This increases our ability to make accurate judgments about others. Multichannel Nonverbal Communication • Except for certain specific situations, such as talking on the telephone, everyday life is made up of multichannel nonverbal social interaction. • Typically, many nonverbal cues are available to us when we talk to or observe other people. • How do we use this information? • And how accurately do we use it? Gender and Nonverbal Communication In general, women are better at encoding and decoding nonverbal cues. Source of images: Microsoft Office Online. Gender and Nonverbal Communication One exception is that women are less accurate at detecting deception. Source of images: Microsoft Office Online. Gender and Nonverbal Communication Social role theory of sex differences suggests that this is because women have learned different skills, and one is to be polite and overlook lying. Source of images: Microsoft Office Online. Gender and Nonverbal Communication According to Alice Eagly’s social role theory, most societies have a division of labor based on gender: • Men work in jobs outside the home. Source of images: Microsoft Office Online. Gender and Nonverbal Communication According to Alice Eagly’s social role theory, most societies have a division of labor based on gender: • Men work in jobs outside the home. • Women work within the home. Source of images: Microsoft Office Online. Gender and Nonverbal Communication This division of labor has important consequences. • First, gender-role expectations arise: Members of the society expect men and women to have certain attributes that are consistent with their role. Thus women are expected to be more nurturing, friendly, expressive, and sensitive than men because of their primary role as caregivers to children and elderly family members. Gender and Nonverbal Communication This division of labor has important consequences. • Second, men and women develop different sets of skills and attitudes, based on their experiences in their gender roles. Source of images: Microsoft Office Online. Gender and Nonverbal Communication This division of labor has important consequences. • Second, men and women develop different sets of skills and attitudes, based on their experiences in their gender roles. • Finally, because women are less powerful in many societies and less likely to occupy roles of higher status, it becomes more important for women to learn to be accommodating and polite than it is for men. Implicit Personality Theories: Filling in the Blanks. • To understand other people, we observe their behavior but we also infer their feelings, traits, and motives. • To do so, we use general notions or schemas about which personality traits go together in one person. Implicit Personality Theories: Filling in the Blanks. Implicit Personality Theory A type of schema people use to group various kinds of personality traits together; for example, many people believe that someone who is kind is generous as well. • If someone is kind, our implicit personality theory tells us he or she is probably generous as well. • Similarly, we assume that a stingy person is also irritable. Implicit Personality Theories: Filling in the Blanks. But relying on schemas can also lead us astray. • We might make the wrong assumptions about an individual. • We might even resort to stereotypical thinking, where our schema, or stereotype, leads us to believe that the individual is like all the other members of his or her group. Culture and Implicit Personality Theories These general notions, or schemas, are shared by people in a culture, and are passed from one generation to another. Source of images: Microsoft Office Online. Culture and Implicit Personality Theories A strong implicit personality theory in this culture involves physical attractiveness. We presume that “what is beautiful is good”—that people with physical beauty will also have a whole host of other wonderful qualities. Source of image: Microsoft Office Online. Culture and Implicit Personality Theories In China, an implicit personality theory describes a person who embodies traditional Chinese values: creating and maintaining interpersonal harmony, inner harmony, and ren qin (a focus on relationships). Source of image: Microsoft Office Online. Culture and Implicit Personality Theories In Western cultures, saying someone has an “artistic personality” implies that the person is creative, intense, and temperamental and has an unconventional lifestyle. The Chinese, however, do not have a schema or implicit personality theory for an artistic type. Source of image: Microsoft Office Online. Culture and Implicit Personality Theories Conversely, in China, there are categories of personality that do not exist in Western cultures. For example, a shi gú person is someone who is worldly, devoted to his or her family, socially skillful, and somewhat reserved. Source of image: Microsoft Office Online. Causal Attribution: Answering the “Why” Question If an acquaintance says, “It’s great to see you!” does she really mean it? • Perhaps she is acting more thrilled than she really feels, out of politeness. • Perhaps she is outright lying and really can’t stand you. The point is that even though nonverbal communication is sometimes easy to decode and our implicit personality theories can streamline the way we form impressions, there is still substantial ambiguity as to what a person’s behavior really means. Source of image: Microsoft Office Online. Causal Attribution: Answering the “Why” Question According to attribution theory, we try to determine why people do what they do in order to uncover the feelings and traits that are behind their actions. This helps us understand and predict our social world. The Nature of the Attribution Process Fritz Heider (1958) is frequently referred to as the father of attribution theory. Heider discussed what he called “naive” or “commonsense” psychology. In his view, people were like amateur scientists, trying to understand other people’s behavior by piecing together information until they arrived at a reasonable explanation or cause. Heider was intrigued by what seemed reasonable to people and by how they arrived at their conclusions. The Nature of the Attribution Process When trying to decide what causes people’s behavior, we can make one of two attributions: • An internal, dispositional attribution or • An external, situational attribution. Internal Attribution The inference that a person is behaving in a certain way because of something about the person, such as attitude, character, or personality. External Attribution The inference that a person is behaving a certain way because of something about the situation he or she is in. The assumption is that most people would respond the same way in that situation. The Nature of the Attribution Process Satisfied spouses tend to show one pattern: • Internal attributions for their partners’ positive behaviors (e.g., “She helped me because she’s such a generous person”). • External attributions for their partners’ negative behaviors (e.g., “He said something mean because he’s so stressed at work this week”). In contrast, spouses in distressed marriages tend to display the opposite pattern: • Their partners’ positive behaviors are chalked up to external causes (e.g., “She helped me because she wanted to impress our friends”). • Negative behaviors are attributed to internal causes (e.g., “He said something mean because he’s a totally selfcentered jerk”). The Nature of the Attribution Process Although either type of attribution is always possible, Heider (1958) noted that we tend to see the causes of a person’s behavior as residing in that person (internal explanation). • We are perceptually focused on people— they are who we notice. • The situation (the external explanation), which is often hard to see and hard to describe, may be overlooked. The Covariation Model: Internal versus External Attributions Harold Kelley’s major contribution to attribution theory was the idea that we notice and think about more than one piece of information when we form an impression of another person. Covariation Model A theory that states that to form an attribution about what caused a person’s behavior, we systematically note the pattern between the presence or absence of possible causal factors and whether or not the behavior occurs. The Covariation Model: Internal versus External Attributions The covariation model focuses on observations of behavior across time, place, actors, and targets. It examines how the perceiver chooses either an internal or an external attribution. We make such choices by using information on: • Consensus, • Distinctiveness, • Consistency. Consensus Information Information about the extent to which other people behave the same way toward the same stimulus as the actor does. Distinctiveness Information Information about the extent to which one particular actor behaves in the same way to different stimuli. Consistency Information Information about the extent to which the behavior between one actor and one stimulus is the same across time and circumstances. The Correspondence Bias: People as Personality Psychologists Specific errors or biases plague the attribution process. One common shortcut is the correspondence bias: the tendency to believe that people’s behavior matches (corresponds to) their dispositions. The Correspondence Bias: People as Personality Psychologists • The pervasive, fundamental theory or schema most of us have about human behavior is that people do what they do because of the kind of people they are, not because of the situation they are in. • When thinking this way, we are more like personality psychologists, who see behavior as stemming from internal dispositions and traits, than like social psychologists, who focus on the impact of social situations on behavior. The Correspondence Bias: People as Personality Psychologists The correspondence bias is so pervasive that many social psychologists call it the fundamental attribution error. Source of image: Microsoft Office Online. The Correspondence Bias: People as Personality Psychologists One reason is that when we try to explain someone’s behavior, our focus of attention is usually on the person, not on the surrounding situation. If we don’t know someone made a F earlier in the day, we can’t use that situational information to help us understand her current behavior. And even when we know her situation, we still don’t know how she interprets it. The F may not have upset her if she’s planning to drop the course anyway. Source of image: Microsoft Office Online. The Correspondence Bias: People as Personality Psychologists We can’t see the situation, so we ignore its importance. People, not the situation, have perceptual salience for us. We pay attention to them, and we tend to think that they alone cause their behavior. Perceptual Salience The seeming importance of information that is the focus of people’s attention. Source of image: Microsoft Office Online. The Correspondence Bias: People as Personality Psychologists The culprit is one of the mental shortcuts we discussed in Chapter 3: the anchoring and adjustment heuristic. The correspondence bias is another byproduct of this shortcut. When making attributions, people use the focus of their attention as a starting point. Source of image: Microsoft Office Online. The Two-Step Process In sum, we go through a two-step process when we make attributions. 1. 2. First, we make an internal attribution; we assume that a person’s behavior was due to something about that person. Then we attempt to adjust this attribution by considering the situation the person was in. But we often don’t make enough of an adjustment in this second step. The Two-Step Process In sum, we go through a two-step process when we make attributions. 1. First, we make an internal attribution; we assume that a person’s behavior was due to something about that person. 2. Then we attempt to adjust this attribution by considering the situation the person was in. But we often don’t make enough of an adjustment in this second step. Why? Because the first step occurs quickly and spontaneously whereas the second step requires more effort and conscious attention. The Two-Step Process We will engage in the second step of attributional processing if we • Consciously slow down and think carefully before reaching a judgment, • Are motivated to reach as accurate a judgment as possible, or • Are suspicious about the behavior of the target person (e.g., we suspect lying). Culture and the Correspondence Bias For decades, it was taken for granted that the correspondence bias was universal: People everywhere, we thought, applied this cognitive shortcut when forming attributions. Source of image: Microsoft Office Online. Culture and the Correspondence Bias People from individualistic and collectivistic cultures both demonstrate the correspondence bias. Members of collectivist cultures are more sensitive to situational causes of behavior and more likely to rely on situational explanations, as long as situational variables are salient. Culture and the Correspondence Bias North American and some other Western cultures stress individual autonomy. A person is perceived as independent and self-contained; his or her behavior reflects internal traits, motives, and values. In contrast, East Asian cultures such as those in China, Japan, and Korea stress group autonomy. The individual derives his or her sense of self from the social group to which he or she belongs. Culture and the Correspondence Bias It would be a mistake to think that members of collectivist cultures don’t make dispositional attributions. They do—it’s just a matter of degree. Source of image: Microsoft Office Online. The Actor/Observer Difference The actor-observer difference is an amplification of the correspondence bias: We tend to see other people’s behavior as dispositionally caused, while we are more likely to see our own behavior as situationally caused. The effect occurs because perceptual salience and information availability differ for the actor and the observer. Source of image: Microsoft Office Online. The Actor/Observer Difference Actors have more information about themselves than observers do. Actors know how they’ve behaved over the years; they know what happened to them that morning. They are far more aware than observers are of both the similarities and the differences in their behavior over time and across situations terms, actors have far more consistency and distinctiveness information about themselves than observers do. Self-Serving Attributions Self-Serving Attributions Explanations for one’s successes that credit internal, dispositional factors and explanations for one’s failures that blame external, situational factors. Defensive Attributions Explanations for behavior that avoid feelings of vulnerability and mortality. Self-Serving Attributions Why do we make self-serving attributions? 1. Most people try to maintain their self-esteem whenever possible, even if that means distorting reality by changing a thought or belief. • We are particularly likely to engage in self-serving attributions when we fail at something and we feel we can’t improve at it. • The external attribution truly protects our selfesteem, as there is little hope we can do better in the future. • But if we believe we can improve, we’re more likely to attribute our current failure to internal causes and then work on improving. Self-Serving Attributions Why do we make self-serving attributions? 1. Most people try to maintain their self-esteem whenever possible, even if that means distorting reality by changing a thought or belief. 2. We want people to think well of us and to admire us. Telling others that our poor performance was due to some external cause puts a “good face” on failure; many people call this strategy “making excuses.” Self-Serving Attributions Why do we make self-serving attributions? 1. Most people try to maintain their self-esteem whenever possible, even if that means distorting reality by changing a thought or belief. 2. We want people to think well of us and to admire us. Telling others that our poor performance was due to some external cause puts a “good face” on failure; many people call this strategy “making excuses.” 3. We know more about our own efforts than we do about other people’s. Self-Serving Attributions • One form of defensive attribution is to believe that bad things happen only to bad people or at least, only to people who make stupid mistakes or poor choices. • Therefore, bad things won’t happen to us because we won’t be that stupid or careless. • Melvin Lerner called this the belief in a just world—the assumption that people get what they deserve and deserve what they get. Source of image: Microsoft Office Online. Self-Serving Attributions The just world belief has unfortunate consequences: • Victims of crimes or accidents are often seen as causing their own fate. • People tend to believe that rape victims are to blame for the rape. • Battered wives are often seen as responsible for their abusive husbands’ actions. Source of image: Microsoft Office Online. Culture and Other Attributional Biases There is some evidence for cross-cultural differences in the Actor-Observer Effect and in Self-Serving and Defensive Attributions. Typically, the difference occurs between Western, individualistic cultures and Eastern, collectivistic cultures. How Accurate Are Our Attributions and Impressions? Our impressions are sometimes wrong because of the mental shortcuts we use when forming social judgments. To improve the accuracy of your attributions, remember that the mental shortcuts we use, such as the correspondence bias, can lead us to the wrong conclusions sometimes. Even with such biases operating, we are quite accurate perceivers of other people. We do very well most of the time. In fact, most of us are more accurate than we realize. How Accurate Are Our Attributions and Impressions? Our impressions are sometimes wrong because of the mental shortcuts we use when forming social judgments. In short, we are capable of To improve the accuracy of your attributions, remember that making the mental shortcuts we use, such as the both stunningly correspondence bias, can lead us to the wrong accurate assessments of conclusions sometimes. Even with such biases we are quite accurate people andoperating, horrific perceivers of other people. We do attributional very well most of themistakes. time. In fact, most of us are more accurate than we realize. 6th edition Social Psychology Elliot Aronson University of California, Santa Cruz Timothy D. Wilson University of Virginia Robin M. Akert Wellesley College slides by Travis Langley Henderson State University