CDI slide template

advertisement

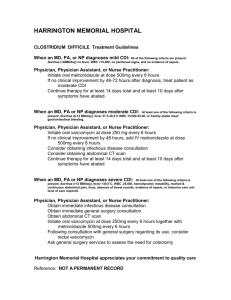

CONVENTIONAL TREATMENT OPTIONS SLIDE RESOURCE SET FDX/13/0068/EUb | August 2013 Snapshot of treatment for initial episodes of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) Treatments used in an initial episode of CDI in a 2008 European survey 0.2% 18% Oral metronidazole Intravenous metronidazole 11% Oral vancomycin Intracolonic vancomycin 71% Bauer MP, et al. Lancet 2011;377:63–73. FDX/12/0076/EUf | EK206 Rates of clinical cure for metronidazole and vancomycin p=0.36 Clinical cure (%) 100 p=0.02 98 p=0.006 97 97 90 Metronidazole 84 80 Vancomycin 74 60 40 20 0 37/ 41 39/ 40 Mild CDI 28/ 38 30/ 31 Severe CDI 66/ 79 69/ 71 All cases Note: patients were stratified by mild or severe disease based on a severity assessment score developed for this study. Patients received one point each for age >60 years, temperature >38.3°C, albumin level <2.5 mg/dL, or peripheral white blood cell count >15,000 cells/mm 3 within 48 hours of enrolment. Two points were given for endoscopic evidence of pseudomembranous colitis or treatment in an intensive care unit. Patients with ≥2 points were considered to have severe CDI Zar FA, et al. Clin Infect Dis 2007;45:302–7. FDX/12/0076/EUf EK205 Rates of clinical success for metronidazole and vancomycin Rates of clinical success in two identical, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, parallel-group trials p=NS p=NS p<0.05 Clinical success (%) 100 81.3 80 81.1 80.8 72.0 73.3 Study 301 (n=277) Study 302 (n=260) 72.7 60 Metronidazole (375 mg qid) Vancomycin (125 mg qid) 40 20 0 Pooled analysis (n=537) Clinical success was defined as diarrhoea resolution and absence of severe abdominal discomfort due to CDI on Day 10; NS, not significant; qid, four times daily Johnson S, et al. Poster presented at IDWeek 2012; 818. FDX/12/0076/Euj | OC104 Clinical limitations associated with current treatments for CDI • Although metronidazole and vancomycin are effective in a first episode of CDI, therapy remains suboptimal • Among the most significant drawbacks of current therapy for CDI are: – Rates of treatment failure with metronidazole of up to 18%1 – Rates of recurrent infection following treatment with metronidazole and vancomycin of up to 25% within 30 days following treatment2–4 – Risk of overgrowth of vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) in patients who are already colonised with VRE5 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Aslam S, et al. Lancet Infect Dis 2005;5:549–57; Louie TL, et al. N Engl J Med 2011;364:422–31; Lowy I, et al. N Engl J Med 2010;362:197–205; Bouza E, et al. Clin Microbiol Infect 2008;14(Suppl 7):S103–4; Al-Nassir WN, et al. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2008;52:2403–6. FDX/12/0087/EUu | slide 041 Is there an increasing treatment failure rate with metronidazole? Average rate of treatment failure in patients receiving metronidazole Treatment failure (%) 25 20 18.3 15 10 5 3.6 2.4 0 1980s 1990s Adapted from Aslam S, et al. Lancet Infect Dis 2005;5:549–57. 2000s Note: the dates relate to the year of publication not the year of the study FDX/12/0076/EUf | EK213 The incidence of recurrent CDI 1st recurrence of CDI Initial episode of CDI 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Recurrence(s) of CDI Up to 25% of patients have recurrent CDI1–3 Louie TJ, et al. N Engl J Med 2011;364:422–31; Lowy I, et al. N Engl J Med 2010;362:197–205; Bouza E, et al. Clin Microbiol Infect 2008;4(Suppl 7):S103–4; McFarland LV, et al. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:1969–75; McFarland LV, et al. JAMA 1994;271:1913–8. ~45–65% of patients have further recurrences4,5 FDX/12/0076/EUb | SJ122 Rates of disease recurrence with metronidazole and vancomycin (1) 29 Recurrence (%) 30 28 Metronidazole 21 20 10 21 Vancomycin 18 7 0 Pre-2000 Post-2000 Adapted from Aslam S, et al. Lancet Infect Dis 2005;5:549–57. Combined Note: the dates relate to the year of publication not the year of the study FDX/12/0076/EUa MW303 Rates of disease recurrence with metronidazole and vancomycin (2) Rates of recurrence in two identical, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, parallel-group trials p=NS p=NS p=NS 50 Metronidazole Vancomycin Recurrence (%) 40 30 27.1 23.4 23.0 18.9 17.6 20 20.6 10 0 Study 301 (n=277) Study 302 (n=260) Johnson S, et al. Poster presented at IDWeek 2012; 818. Pooled analysis (n=537) NS, not significant FDX/12/0076/Euj | OC105 Rates of recurrence for metronidazole and vancomycin grouped by age CDI recurrence during 4-week follow-up in patients from two pooled, randomised, double-blind, parallel-group trials p=NS p=NS p=NS Recurrence (%) 50 Metronidazole 40 30 20 Vancomycin 36.2 26.2 19.8 19.2 21.8 23.2 10 0 Age ≤65 years • Age >65 years Age >75 years* Recurrence increased with increasing age in metronidazole-treated subjects but remained relatively stable in vancomycin-treated subjects Johnson S, et al. Poster presented at IDWeek 2012; 818. *Subset of subjects aged >65 years; NS, not significant FDX/12/0076/EUq | EB113 Rates of recurrence for metronidazole and vancomycin grouped by sex CDI recurrence during 4-week follow-up in patients from two pooled, randomised, double-blind, parallel-group trials p<0.05 p=NS Recurrence (%) 50 Metronidazole Vancomycin 40 30 20 23.7 22.5 24.0 17.4 10 0 Males • Females Male subjects treated with vancomycin had significantly fewer (p<0.05) recurrences vs males treated with metronidazole Johnson S, et al. Poster presented at IDWeek 2012; 818. NS, not significant FDX/12/0076/EUq | EB112 Rates of recurrence for metronidazole and vancomycin grouped by C. difficile strain CDI recurrence during 4-week follow-up in patients from two pooled, randomised, double-blind, parallel-group trials p=NS p=NS Recurrence (%) 50 Metronidazole 40 Vancomycin 32.4 30 29.0 24.4 18.8 20 10 0 BI (027) strain Non-BI (non-027) strain Johnson S, et al. Poster presented at IDWeek 2012; 818. BI, restriction-endonuclease analysis group BI strain of C. difficile (also known as NAP1/027); NS, not significant FDX/12/0076/EUq | EB115 Differences in estimates of CDI recurrence and its definition across Europe Country Estimate Definition Austria 16% A second episode within 60 days of the first Denmark 11% Not reported France 1% Not reported 3% >40 days after first episode 4% Toxin-positive diarrhoea <30 days post treatment 14% New CDI episode during the next chemotherapy course 18% Within 8 weeks of the previous episode 36% New CDI episode during 60-day follow-up, ≥48 hours after treatment Germany Ireland 3–4%,* 10%† The Netherlands Relapse of CDI >8 weeks after first infection 16% Episode occurring ≤8 weeks after onset of an earlier case 22% Diarrhoea <30 days after initial clinical improvement Poland 17% Increased frequency of loose stools with new signs of severe colitis Spain 6–18% Switzerland UK 4% Not reported Positive toxin or stool culture up to 3 months from first diagnosis 0–2% 30-day recurrence 8–11% Toxin-positive diarrhoea up to 4 weeks following treatment 15% Over 12 months 20% Return of diarrhoea ≤30 days after completion of treatment Wiegand PN, et al. J Hosp Infect 2012;81:1–14. *Ribotypes 001, 014 and 078; †Ribotype 027 FDX/12/0076/EUq | EB107 Patients with CDI recurrence (%) Vancomycin regimens for recurrent CDI post hoc analysis from two trials (n=163) 80 *p<0.05 compared with vancomycin 1 g/day 70 60 50 40 * 30 20 * 10 0 Vancomycin (1 g/day) × 7–14 days Vancomycin (2 g/day) × 7–14 days McFarland LV, et al. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:1769–75. Tapered vancomycin Pulsed vancomycin FDX/12/0076/EUr | SJ230 Rationale for a new treatment • CDI remains a disease for which there are significant unmet needs e.g.: – Therapy to provide sustained clinical cure (defined as clinical cure without recurrence)1 – Therapy to reduce recurrence (relapse and/or reinfection)1 – Better identification of patients at risk of recurrence or those for whom the impact of recurrence would be most dramatic2 • New approaches under investigation but data from large-scale randomised controlled trials are lacking3 • Management strategies to treat acute episodes of CDI effectively and markedly reduce the risk of recurrence would represent a significant therapeutic advance4 1. 2. 3. 4. Cornely OA. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012;18(Suppl 6):28–35; Kelly CP. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012;18(Suppl 6):21–7; Bauer MP, et al. Clin Microbiol Infect 2009;15:1067–79; Bouza E. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012;18(Suppl 6):5–12. FDX/12/0076/EUk | MB145 Faecal microbiota therapy for CDI Study Indication Eiseman et al. 1958. Severe PMC MacConnachie et al. 2009. Patients Administration Outcome 4 Enema Resolution in all patients Recurrent CDI 15 NG tube 86.7% clinical response Arkkila et al. 2010. Recurrent CDI 37 Colonoscope 92% eradication Khoruts et al. 2010. Recurrent CDI 1 Colonoscope Eradication Yoon, Brandt. 2010. Recurrent CDI/PMC 12 Colonoscope 100% clinical response Rohike et al. 2010. Recurrent CDI 19 Colonoscope 94.7% clinical response Silverman et al. 2010. Recurrent CDI 7 Enema 100% asymptomatic Garborg et al. 2010. Recurrent CDI 40 Endoscope 82.5% eradication Russell et al. 2010. Recurrent CDI 1 NG tube Resolution of symptoms Kelly et al. 2010. Recurrent CDI 12 Colonoscope 100% clinical response Mellow et al. 2010. Recurrent CDI 13 Colonoscope 92.3% clinical response Kassam et al. 2010. CDI 14 Enema 100% clinical resolution Kelly et al. 2011. Recurrent CDI 26 Colonoscope 92% clinical resolution Borody TJ, Khoruts A. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;9:88–96. NG, nasogastric; PMC, pseudomembranous colitis FDX/12/0100/EUk | JC129 Faecal microbiota therapy for recurrent CDI: study design van Nood et al. trial Oral vancomycin 500 mg qid, 14 days Oral vancomycin 500 mg qid, 14 days Bowel lavage 1× Oral vancomycin 500 mg qid, 4 days Bowel lavage 1× Donor faeces 1× Endpoints1,2 • Diarrhoea (≥3×/day) and C. difficile toxin on Days 35 and 70 • Quality of life, days spent in isolation, days admitted to the hospital, attributable costs • Psychological analysis of effect of faecal transplant • Follow-up 10 weeks, cross-over if failure in antibiotic group 1. van Nood E, et al. N Engl J Med 2013;368:407–15; 2. Protocol to: van Nood E, et al. N Engl J Med 2013;368:407–15. qid, four-times daily FDX/12/0100/EUk | JC132 Duodenal faecal microbiota transplantation vs vancomycin plus lavage p<0.001 p<0.001 p=0.008 Rates of cure without relapse (%) p=0.003 100 80 93.8 81.3 60 30.8 40 23.1 20 0 First infusion of donor faeces (n=16) Infusion of donor faeces overall (n=16) Vancomycin (n=13) Vancomycin with bowel lavage (n=13) • Study stopped after interim analysis • No significant differences in adverse events among study groups, except for mild diarrhoea and abdominal cramping in the infusion group on the day of infusion van Nood E, et al. N Engl J Med 2013;368:407–15. FDX/12/0076/EUf | EK242 Microbiota diversity in patients before and after faecal infusion versus healthy donors Simpson’s reciprocal index 250 200 150 100 50 0 Donors van Nood E et al. N Engl J Med 2013;368:407-415 van Nood E, et al. N Engl J Med 2013;368:407–15. Patients before infusion Patients after infusion FDX/12/0100/EUk | JC135 Faecal bacteriotherapy: limitations • No supporting data from prospective, randomised controlled trials1–3 • Very limited data on long-term safety – Administration via colonoscopy, nasogastric tube or retention enema associated with some risk4 – Potential transmission of infectious agents contained in the donor stool may also carry inherent risks4 • Acceptability of the procedure may be an issue5 – Patients and physicians reluctant to choose donor-faeces infusion at an early stage6 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Gough E, et al. Clin Infect Dis 2011;53:994–1002; Anderson JL, et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2012;36:503–16; Guo B, et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2012;35:865–75; Aas J, et al. Clin Infect Dis 2003;36:580–5; Hedge DD, et al. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2008;4:949–64; van Nood E, et al. N Engl J Med 2013;368:407–15. FDX/12/0076/EUk | MB137 Issues surrounding the clinical application of faecal transplantation • Acceptability1–3 • Patient selection • • 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. – Immunocompromised3,4 – Concomitant antibiotic therapy5 – Allergens (e.g. nuts)4 Donor screening – Epstein–Barr virus,5 cytomegalovirus,5 HIV,4–6 hepatitis A/B/C4–7 – Syphilis,7 C. difficile5–7 – Enteric pathogens including parasites5–7 – No antibiotics in previous 3 months4 Cost – Screening6 – Procedure-related6 Yoon SS, Brandt LJ. J Clin Gastroenterol 2010;44:562–6; Hedge DD, et al. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2008;4:949–64; Borody TJ, Khoruts A. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;9:88–96; Bakken JS, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;9:1044–9; van Nood E, et al. N Engl J Med 2013;368:407–15; Rohlke F, Stollman N. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2012;5:403–20; Aas J, et al. Clin Infect Dis 2003;36:580–5. FDX/12/0100/EUk | JC136