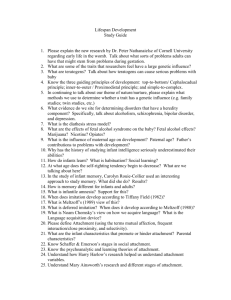

Attachment theory & Emotionally Focused Therapy

advertisement

…the capacity to form and maintain healthy emotional relationships which generally begin to develop in early childhood – Enduring bond with “special” person – Security & safety within context of this relationship – Includes soothing, comfort, & pleasure – Loss or threat of loss of special person results in distress Having close connections is vital to every aspect of our health – mental, emotional, and physical. Hawkley – U. of Chicago Calculates that loneliness raises blood pressure to the point where the risk of heart attack and stroke is doubled. House – U. of Michigan › Emotional isolation is more dangerous health risk than smoking or high blood pressure. Patients with congestive heart failure – the state of their marriage is as good a predictor of survival after four yeas as the severity of the symptoms. Conflict with and hostile criticism from loved ones increase our self-doubts and create a sense of helplessness › These are classic triggers for depression › We live in a epidemic of anxiety and depression The California Divorce Mediation Project reported that the most common reason for divorcing given by close to 80% of all men and women was gradually growing apart and losing a sense of closeness, and not feeling loved and appreciated. › Severe and intense fighting were endorsed by only 40% of the couples. Hundreds of studies now show that positive loving connections with others protect us from stress and help us cope better with life’s challenges and traumas. Simply holding the hand of a loving partner can affect us profoundly › Research has found that this act literally calms jittery neurons in the brain. People we love are “hidden regulators” of our bodily processes and our emotional lives. In 1939, women ranked love fifth as a factor in choosing a mate By the 1990s, it topped the list for both women and men. College students now say that their key expectation from marriage is “emotional security.” 1. Attachment is an innate motivating force › › Seeking and maintaining contact with significant others is innate. This occurs throughout the life span. 2. Secure dependency complements autonomy › › › › › No such thing as complete independence or overdependency There is only effective and ineffective dependence Secure dependence fosters autonomy and self-confidence The more secure attached we are the more separate and different we can be. Health means maintaining a felt sense of interdependency, rather than being selfsufficient and separate from others. 3. Attachment offers a safe haven › › › The presence of attachment figures provides comfort and security while perceived inaccessibility creates distress. Proximity is the natural antidote to feelings of anxiety and vulnerability Positive attachments offers a safe haven that offer a buffer against effects of stress and uncertainty. 4. Attachment offers a secure base › › › Gives base from which individuals can explore their world and most adaptively respond to their environment. Secure base encourages exploration and a cognitive openness to new information. When we have this felt security, we are better able to reach out and offer support for others. 5. Accessibility and Responsiveness builds bonds › › › › › › Building blocks for secure attachment are emotional accessibility and responsiveness One can be physically present but emotionally absent Emotional engagement and the trust that this engagement will be there when needed is most crucial. Any response, even anger, is better than none. Emotion is the key. If there is no engagement, no emotional responsiveness, then the message is “your signals do not matter to me and there is no connection between us.” 6. Fear and uncertainty activate attachment needs › › When an individual is threatened attachment needs for comfort and connection become salient and compelling, and attachment behaviors are activated. Attachment to key others is our primary protection against feelings of helplessness and meaningless. 7. The process of separation distress is predictable › › › If attachment behaviors fail to evoke comforting responsiveness and contact from attachment figures, a predictable process of protest, clinging, depression and despair, ending eventually in detachment. Depression is a natural response to loss of connection Anger can be seen as an attempt to make contact with an inaccessible attachment figure. 8. Finite number of insecure forms of engagement can be identified. › › There are a number of ways that we have to deal with the unresponsiveness of attachment figures. Only so many ways of coping from a negative response to the question “Can I depend on you when I need you?” 9. Attachment involves working models of self and others › › Attachment strategies reflect ways of processing and dealing with emotion These models of self and others come from thousands of interactions, and become expectations and biases that are carried forward into new relationships. 10. Isolation and loss are inherently traumatizing › › Attachment theory describes and explores the trauma of deprivation, loss, rejection, and abandonment by those we need the most and the enormous impact it has on us. These events have a major impact on personality formation and on a person’s ability to deal with other stresses in life. No Connection › Lack of emotion › Unresponsive › Emotionally unavailable Connection › Emotion is key › Are responsive to one another › Are emotionally available to one another Building blocks of a secure bond. Partner can be physically present but emotionally absent. Emotional engagement and the trust that this engagement will be there when needed is crucial. When there is no engagement, no emotional responsiveness, the message reads “you don’t matter to me.” Emotion is central to individuals being accessible and ‘emotionally’ responsive to one another › Any response, even anger, is better than none. It is in our closest relationships where our strongest emotions arise and where they seem to have most impact Emotion tells us and communicates to others what our motivations and needs are They can be seen as the ‘music’ to the relationship dance This means staying open to your partner even when you have doubts and feel insecure. It often means being willing to struggle to make sense of your emotions so these emotions are not so overwhelming You can then step back from disconnection and can tune in to your lover’s attachment cues. This means tuning into your partner and showing that his or her emotions have an impact on you. It means accepting and placing a priority on the emotional signals your partner conveys and sending clear signals of comfort and caring when your partner needs them. Sensitive responsiveness always touches us emotionally and calms us on a physical level. The dictionary defines engaged as being absorbed, attracted, pulled, captivated, pledged, involved. Emotional engagement means the very special kinds of attention that we give only to a loved one. We gaze at them longer, touch them more. Often we talk of this as being “emotionally present.” In these moments of safe attunement and connection › Both partners can hear each other’s attachment cry and respond with soothing care, › Forging a new bond that can withstand differences, wounds, and the test of time. Often found in small moments of time › Its in these moments of safe connection that change everything › They provide a reassuring answer to the question “are you there for me” › Once partners know how to speak to their need and bring each other close, every trial they face together simply makes their love stronger. These moments of connections create new patterns in the relationship – a new dance If you know your loved one is there and will come when you call, you are more confident of your worth and your value. The world is less intimidating when you have another to count on and you know that you are not alone. Vulnerability Compassion › One becomes vulnerable and the other responds with compassion. Vulnerability Vulnerability › One becomes vulnerable and the other responds with becoming vulnerable as well. Susan Johnson Leslie Greenberg EFT is collaborative combining Experimental and Rogerian techniques with Structural systemic interventions. EFT is based on clear, explicit conceptualizations of relationship distress and adult love. These conceptualizations are supported by empirical research on the nature of marital distress and adult attachment. Key moves and moments in the change process have been mapped into nine steps and three change events. To expand and re-organize key emotional responses–the music of the attachment dance. To create a shift in partners' interactional positions and develop new cycles of interaction. To foster the creation of a secure bond between partners. Relationship distress is maintained by absorbing negative affect. Affect reflects and primes rigid, constricted patterns of interaction. Patterns make safe emotional engagement difficult and create insecure bonding. Rigid repetitive interactional patterns: › No exits – no detours/ repair impossible › Rigid narrow positions – fight/flight/freeze › Most common patterns Criticize, complain, express contempt Defend, distance, stonewall Results: self reinforcing cycles or reactivity/self protective strategies Partners cannot attune to one another because they are so absorbed in their own negative affect Cannot communicate because of their own state. Gottman 1979 – absorbing states of negative affect: everything leads in, nothing leads out. 70 – 73% recovery rate in 10-12 sessions. Two-year follow- up on relationship distress, depression, and parental stress – results stable – 60% continue to improve. Depression significantly reduced. Best predictor of success – female faith in partner’s caring (Not initial distress level). Looks within at how partners construct their emotional experience of relatedness Looks between at how partners engage each other. Experiential › Present › Primary Affect Systemic › Process (time) › Positions / Patterns The counselor is a process consultant Present experience › Deal with the past when it comes into the present to validate client’s responses as it relates to how they coped/survived › When emotion is re-experienced it is now in the present › Focus is on current positions/patterns › Don’t ask “why”, focus on what is. Primary emotions › Validating and moving from secondary to primary emotions › Stay with emotions, create safe haven › Organize the emotion of a past experience so that client can engage in the here & now Process patterns › Look individually how each person is processing in the moment › “What happens…then what…then what” Positions › The position each partner is taking in the relationship › Work to create new position & new patterns Stage 1: De-escalation Stage 2: Restructuring the Bond Stage 3: Consolidation Steps 1 – 4 Assessment & Cycle De-escalation 1. Alliance & assessment: Creating an alliance and delineating conflict issues in the core attachment struggle. What are they fighting about and how are they related to core attachment issues. Steps 1 – 4 Assessment & Cycle De-escalation 2. Identify the negative interaction cycle, and each partner’s position in that cycle. Goal is to see the cycle in action and then identify and describe it to the couple and work to stop it. Steps 1 – 4 Assessment & Cycle De-escalation 3. Access unacknowledged emotions underlying interactional positions. Goal is to help each partner to access and accept their unacknowledged feelings that are influencing their behavior. › Both partners are to reprocess and crystallize their own experience in the relationship so that they can become emotionally open to the other person. Steps 1 – 4 Assessment & Cycle De-escalation 4. Reframe the problem in terms of underlying feelings, attachment needs, and negative cycle. The cycle is framed as the common enemy (externalizing the problem) and the source of the partner’s emotional deprivation and distress. Steps 5 – 7 Changing Interactional Positions and creating new bonding events 5. Promote identification with disowned attachment emotions, needs, and aspects of self, and integrate these into relationship interactions. Goal is to help the couple redefine their experiences in terms of their unacknowledged emotional needs. Steps 5 – 7 Changing Interactional Positions and creating new bonding events 6. Promote acceptance of the other partner’s experiences and new interactional responses. Goal is to work to get each partner to accept, believe, and trust that what the other partner is describing in terms of underlying emotional needs is accurate. Steps 5 – 7 Changing Interactional Positions and creating new bonding events 7. Facilitate the expression of needs and wants and create emotional engagement and bonding events that redefine the attachment between the partners. Goal is to help couple learn to express their emotional needs and wants directly and create emotional engagement. Steps 8 – 9 Consolidation/Integration 8. Facilitating the emergence of new solutions to old relationship problems. Without the old negative interaction style and with the new emotional connection and attachment, it is easier to develop new solutions to old problems. Steps 8 – 9 Consolidation/Integration 9. Consolidating new positions and new cycles of attachment behaviors. Help couple clearly see and articulate the old and new ways of interacting to help the couple avoid falling back into the old interactional cycle. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Develop an alliance, identify cycle, identify and access underlying emotions, and work to deescalate Engage the withdrawer Soften the pursuer/blamer Create new emotional bonding events and new cycles of interaction Consolidate new cycles of trust, connection and safety, and apply them to old problems that may still be relevant Johnson, S.M. (2008). Hold Me Tight: Seven Conversations for a Lifetime of Love. New York: Little Brown. Johnson, S.M. (2004). The Practice of Emotionally Focused Marital Therapy: Creating Connection. New York: Bruner / Routledge. Johnson, S.M., Bradley, B., Furrow, J., Lee, A., Palmer, G., Tilley, D., & Woolley, S. (2005) Becoming an Emotionally Focused Couples Therapist : A Work Book. N.Y. Brunner Routledge. Johnson, S.M. & Whiffen, V. (2003). Attachment Processes in Couples and Families. Guilford Press. Johnson, S.M. (2002). Emotionally Focused Couple Therapy with Trauma Survivors: Strengthening Attachment Bonds. Guilford Press.