Introduction to Forecasting

advertisement

Introduction to

(Demand) Forecasting

Topics

•

•

•

•

•

Introduction to (demand) forecasting

Overview of forecasting methods

A generic approach to quantitative forecasting

Time series-based forecasting

Building causal models through multiple linear

regression

• Confidence Intervals and their application in forecasting

Forecasting

• The process of predicting the values of a certain quantity,

Q, over a certain time horizon, T, based on past trends

and/or a number of relevant factors.

• Some forecasted quantities in manufacturing

–

–

–

–

demand

equipment and employee availability

technological forecasts

economic forecasts (e.g., inflation rates, exchange rates, housing

starts, etc.)

• The time horizon depends on

– the nature of the forecasted quantity

– the intended use of the forecast

Forecasting future demand

• Demand forecasting is based on:

– extrapolating to the future past trends observed in the company

sales;

– understanding the impact of various factors on the company future

sales:

•

•

•

•

•

•

market data

strategic plans of the company

technology trends

social/economic/political factors

environmental factors

etc

• Remark: The longer the forecasting horizon, the more

crucial the impact of the factors listed above.

Demand Patterns

• The observed demand is the cumulative result of:

– systematic variation, due to a number of identified factors, and

– a random component, incorporating all the remaining unaccounted

effects.

• Patterns of systematic variation

– seasonal: cyclical patterns related to the calendar (e.g., holidays,

weather)

– cyclical: patterns related to changes of the market size, due to, e.g.,

economics and politics

– business: patterns related to changes in the company market share,

due to e.g., marketing activity and competition

– product life cycle: patterns reflecting changes to the product life

The problem of demand forecasting

– Identify and characterize the systematic

variation, as a set of trends.

– Characterize the variability in the demand.

Forecasting Methods

• Qualitative (Subjective): Incorporate factors like

the forecaster’s intuition, emotions, personal

experience, and value system.

• These methods include:

–

–

–

–

Jury of executive opinion

Sales force composites

Delphi method

Consumer market surveys

Forecasting Methods (cont.)

• Quantitative (Objective): Employ one or more

mathematical models that rely on historical data

and/or causal/indicator variables to forecast

demand.

• Major methods include:

– time series methods: F(t+1) = f (D(t), D(t-1), …)

– causal models:

F(t+1) = f(X1(t), X2(t), …)

Selecting a Forecasting Method

• It should be based on the following considerations:

– Forecasting horizon (validity of extrapolating past data)

– Availability and quality of data

– Lead Times (time pressures)

– Cost of forecasting (understanding the value of

forecasting accuracy)

– Forecasting flexibility (amenability of the model to

revision; quite often, a trade-off between filtering out

noise and the ability of the model to respond to abrupt

and/or drastic changes)

Implementing Quantitative Forecasting

Determine Method

•Time Series

•Causal Model

Collect data:

<Ind.Vars; Obs. Dem.>

Fit an analytical model

to the data:

F(t+1) = f(X1, X2,…)

Update Model

Parameters

Use the model for

forecasting future

demand

Monitor error:

e(t+1) = D(t+1)-F(t+1)

Yes

Model

Valid?

No

- Determine

functional form

- Estimate parameters

- Validate

Time Series-based Forecasting

Basic Model:

D (i ), i 1,..., t

Historical

Data

Time Series

Model

Dˆ (t ), 1,2,...

Forecasts

Remark: The exact model to be used depends on the expected /

observed trends in the data.

Cases typically considered:

• Constant mean series

• Series with linear trend

• Series with seasonalities (and possibly a linear trend)

A constant mean series

14.00

12.00

10.00

8.00

Series1

6.00

4.00

2.00

0.00

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20

The above data points have been sampled from a normal distribution with a

mean value equal to 10.0 and a variance equal to 4.0.

Forecasting constant mean series:

The Moving Average model

The presumed model for the observed data:

D(t ) D e(t )

where

D

is the constant mean of the series and

e(t ) is normally 2distributed with zero mean and some unknown

variance

Then, under a Moving Average of Order N model, denoted as MA(N),

the estimate of D returned at period t, is equal to:

1

ˆ

D (t )

N

N 1

D(t i)

i 0

The forecasting error

• The forecasting error

1

ˆ

(t 1) D (t ) D(t 1)

N

N 1

D(t i) D(t 1)

i 0

• Also

1 N 1

1

E[ (t 1)] E[ D(t i)] E[ D(t 1)] ( ND ) D 0

N i 0

N

1 N 1

1

1 2

2

2

Var[ (t 1)] 2 Var[ D(t i)] Var[ D(t 1)] 2 N (1 )

N i 0

N

N

Forecasting error (cont.)

• (t+1) is normally distributed with the mean and

variance computed in the previous slide.

•

ˆ (t ) D

D

follows a normal distribution with zero

mean and variance 2/N.

Selecting an appropriate order N

• Smaller values of N provide more flexibility.

• Larger values of N provide more accuracy (c.f., the formula for the

variance of the forecasting error).

• Hence, the more stable (stationary) the process, the larger the N.

• In practice, N is selected through trial and error, such that it

minimizes one of the following criteria:

t

1

i)

MAD(t )

| (t ) |

t N i N 1

t

ii) MSD (t ) 1

( (t )) 2

t N i N 1

t

iii)

1

(t )

MAPE(t )

t N i N 1 D(t )

Demonstrating the impact of N on

the model performance

25.00

20.00

15.00

Series1

Series2

Series3

10.00

5.00

40

37

34

31

28

25

22

19

16

13

10

7

4

1

0.00

• blue series: the original data series, distributed according to N(10,4) for the first 20

points, and N(20,4) for the last 20 points.

• magenta series: the predictions of the MA(5) forecasting model.

• yellow series: the predictions of the MA(10) forecasting model.

• Remark: the MA(5) model adjusts faster to the experienced jump of the data mean

value, but the mean estimates that it provides under stationary operation are less accurate

than those provided by the MA(10) model.

Forecasting constant mean series:

The Simple Exponential Smoothing model

• The presumed demand model:

D(t ) D e(t )

where D is an unknown constant and e(t ) is normally distributed

with zero mean and an unknown variance 2 .

• The forecast Dˆ (t ) , at the end of period t:

Dˆ (t ) aD(t ) (1 a) Dˆ (t 1) Dˆ (t 1) a[ D(t ) Dˆ (t 1)]

where (0,1) is known as the “smoothing constant”.

• Remark: The updating equation constitutes a correction of the

previous estimate in the direction suggested by the forecasting error,

D(t ) Dˆ (t 1)

Expanding the Model Recursion

ˆ (t ) aD(t ) (1 a) D

ˆ (t 1)

D

ˆ (t 2)

aD(t) a(1 a)D(t 1) (1 a)2 D

.................................................................................................

t 1

a (1 a ) i D(t i ) (1 a )t Dˆ (0)

i 0

Implications

1. The model considers all the past observations and the

initializing value Dˆ (0) in the determination of the

estimate Dˆ (t ) .

2. The weight of the various data points decreases

exponentially with their age.

3. As 1, the model places more emphasis on the most

recent observations.

4. As t,

E[ Dˆ (t )] D and Var[ D(t 1) Dˆ (t )] 2 2

2a

ˆ

The impact of and of D (0) on

the model performance

25.00

20.00

15.00

Series1

Series2

Series3

Series4

10.00

5.00

40

37

34

31

28

25

22

19

16

13

10

7

4

1

0.00

• dark blue series: the original data series, distributed according to N(10,4) for the first 20

points, and N(20,4) for the last 20 points.

• magenta series: the predictions of the ES(0.2) model initialized at the value of 10.0.

• yellow series: the predictions of the ES(0.2) model initialized as 0.0.

• light blue series: the predictions of the ES(0.8) model initialized at 10.0.

• Remark: the ES(0.8) model adjusts faster to the jump of the series mean value, but the

estimates that it provides under stationary operation are less accurate than those provided by

the ES(0.2) model. Also, notice that the effect of the initial value is only transient.

The inadequacy of SES and MA

models for data with linear trends

12

10

8

Dt

6

SES(0.5)

SES(1.0)

4

2

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

• blue series: a deterministic data series increasing linearly with a slope of 1.0.

• magenta series: the predictions obtained from the SES(0.5) model initialized at

the exact value of 1.0.

• yellow series: the predictions obtained from the SES(1.0) model initialized at

the exact value of 1.0.

• Remark: Both models under-estimate the actual values, with the most inert

model SES(0.5) under-estimating the most. This should be expected since both of

these models (as well as any MA model) essentially average the past

observations. Therefore, neither the MA nor the SES model are appropriate for

forecasting a data series with a linear trend in it.

Forecasting series with linear trend:

The Double Exponential Smoothing Model

The presumed data model:

D(t ) I T t e(t )

where

I is the model intercept, i.e., the unknown mean value for t=0,

T is the model trend, i.e., the mean increase per unit of time, and

e(t ) is normally distributed with zero mean and some unknown

variance 2

The Double Exponential Smoothing

Model (cont.)

The model forecasts at period t for periods t+, =1,2,…, are

given by:

Dˆ (t ) Iˆ(t ) Tˆ (t )

with the quantities Iˆ(t ) and Tˆ (t ) obtained through the following

recursions:

Iˆ(t ) a D(t ) (1 a)[ Iˆ(t 1) Tˆ (t 1)]

Tˆ (t ) b [ Iˆ(t ) Iˆ(t 1)] (1 b ) Tˆ (t 1)

The parameters a and btake values in the interval (0,1) and are the

model smoothing constants, while the values Iˆ(0) and Tˆ (0) are the

initializing values.

The Double Exponential Smoothing

Model (cont.)

• The smoothing constants are chosen by trial and error, using the

MAD, MSD and/or MAPE indices.

• For t, Iˆ(t ) I and Tˆ (t ) T

2

• The variance of the forecasting error, , can be estimated as a

function of the noise variance 2 through techniques similar to

those used in the case of the Simple Exp. Smoothing model, but in

practice, it is frequently approximated by

ˆ 2 1.25MAD(t )

where

MAD(t ) g (t ) (1 g )MAD(t 1)

for some appropriately selected smoothing constant g(0,1) or by

ˆ 2 MSD(t )

DES Example

12

10

8

Dt

6

DES(T0=1)

DES(T0=0)

4

2

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9 10

• blue series: a deterministic data series increasing linearly with a slope of 1.0.

• magenta series: the predictions obtained from the DES(0.5;0.2) model initialized

at the exact value of 1.0.

• yellow series: the predictions obtained from the DES(0.5;0.2) model initialized

at the value of 0.0.

• Remark: In the absence of variability in the original data, the first model is

completely accurate (the blue and the magenta series overlap completely), while

the second model overcomes the deficiency of the wrong initial estimate and

eventually converges to the correct values.

Time Series-based Forecasting:

Accommodating seasonal behavior

The data demonstrate a periodic behavior (and maybe some

additional linear trend).

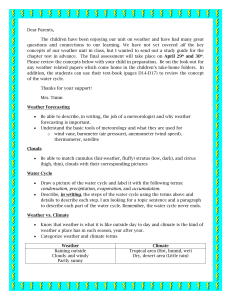

Example: Consider the following data, describing a quarterly

demand over the last 3 years, in 1000’s:

Spring

Summer

Fall

Winter

Total

Year 1

90

180

70

60

400

Year 2

115

230

85

70

500

Year 3

120

290

105

100

615

Seasonal Indices

Plotting the demand data:

350

300

250

200

Series1

150

100

50

0

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

Remarks:

• At each cycle, the demand of a particular season is a fairly stable percentage of

the total demand over the cycle.

• Hence, the ratio of a seasonal demand to the average seasonal demand of the

corresponding cycle will be fairly constant.

• This ratio is characterized as the corresponding seasonal index.

A forecasting methodology

Forecasts for the seasonal demand for subsequent years can be obtained by:

i. estimating the seasonal indices corresponding to the various seasons in the

cycle;

ii. estimating the average seasonal demand for the considered cycle (using, for

instance, a forecasting model for a series with constant mean or linear trend,

depending on the situation);

iii. adjusting the average seasonal demand by multiplying it with the

corresponding seasonal index.

Example (cont.):

Spring

Summer

Fall

Winter

Total

Average

Year 1

90

180

70

60

400

100

Year 2

115

230

85

70

500

125

Year 3

120

290

105

100

615

153.75

SI(1)

0.9

1.8

0.7

0.6

4

SI(2)

0.92

1.84

0.68

0.56

4

SI(3)

0.78

1.88

0.68

0.65

4

SI

0.87

1.84

0.69

0.6

4

Winter’s Method for Seasonal

Forecasting

The presumed model for the observed data:

D(t ) ( I T t ) c(t 1) mod N 1 e(t )

where

• N denotes the number of seasons in a cycle;

• ci, i=1,2,…N, is the seasonal index for the i-th season in the cycle;

• I is the intercept for the de-seasonalized series obtained by dividing the

original demand series with the corresponding seasonal indices;

• T is the trend of the de-seasonalized series;

2

• e(t) is normally distributed with zero mean and some unknown variance

Winter’s Method for Seasonal Forecasting

(cont.)

The model forecasts at period t for periods t+, 1,2,…, are given by:

Dˆ (t ) [ Iˆ(t ) Tˆ (t ) ] cˆ(t 1) mod N 1 (t )

where the quantities Iˆ(t ) , Tˆ (t ) and cˆi (t ), i 1,..., N ,are obtained from the

following recursions, performed in the indicated sequence:

Iˆ(t ) : a

D(t )

(1 a)[ Iˆ(t 1) Tˆ (t 1)]

cˆ(t 1) mod N 1 (t 1)

Tˆ (t ) : b [ Iˆ(t ) Iˆ(t 1)] (1 b ) Tˆ (t 1)

D(t )

cˆ(t 1) mod N 1 (t ) : g

(1 g ) cˆ(t 1) mod N 1 (t 1)

ˆI (t )

cˆi (t ) : cˆi (t 1), i (t 1) mod N 1

The parameters ,b,gtake values in the interval (0,1) and are the model smoothing

constants, while Iˆ (0), Tˆ (0) and cˆi (0), i 1,..., N , are the initializing values.

Causal Models:

Multiple Linear Regression

• The basic model:

D b0 b1 X 1 ... bk X k e

where

• Xi, i=1,…,k, are the model independent variables (otherwise known as the

explanatory variables);

• bi, i=0,…,k, are unknown model parameters;

• e is the a random variable following a normal distribution with zero mean and

some unknown variance 2.

2

• D follows a normal distribution N ( D , ) where

D b0 b1 X 1 ... bk X k

• We need to estimate <b0,b1,…,bk> and 2 from a set of n observations

{ D j ; X 1 j , X 2 j ,..., X kj , j 1,..., n}

Estimating the parameters bi

• The observed data satisfy the following equation:

D1 1 X 11

D 1 X

12

2

... ... ...

Dn 1 X 1n

... X k1 b0 e1

... X k 2 b1 e2

... ... ... ...

... X kn bk en

or in a more concise form

• The vector

d X b e

e d X b

denotes the difference between the actual observations and the corresponding

mean values, and therefore, b̂ is selected such that it minimizes the Euclidean

norm of the resulting vector eˆ d X bˆ .

• The minimizing value for b̂ is equal to bˆ ( X T X ) 1 X T d

• The necessary and sufficient condition for the existence of ( X T X ) 1 is that the

columns of matrix X are linearly independent.

Characterizing the model variance

• An unbiased estimate of 2is given by

SSE

MSE

n k 1

(Mean Squared Error)

where

SSE eˆT eˆ (d X bˆ)T (d X bˆ)

(Sum of Squared Errors)

• The quantity SSE/2 follows a Chi-square distribution with n-k-1 degrees of

freedom.

• Given a point x0T=(1,x10,…,xk0), an unbiased estimator of

D ( x0 )is given by

Dˆ ( x0 ) bˆ0 bˆ1 x10 ... bˆk xk 0

2 T

T

1

• This estimator is normally distributed with mean D ( x0 ) and variance x0 ( X X ) x0

ˆ

• The random variable D ( x0 ) can function also as an estimator for any single

ˆ

observation D(x0). The resulting error D ( x0 ) D( x0 ) will have zero mean and

T

2

T

1

variance [1 x0 ( X X ) x0 ]

Assessing the goodness of fit

• A rigorous characterization of the quality of the resulting approximation can be

obtained through Analysis of Variance, that can be traced in any introductory book

on statistics.

•A more empirical test considers the coefficient of multiple determination

SSR

R

SYY

2

where

SSR bˆT ( X T d ) nd 2 ( Dˆ j d ) 2

n

and

n

1

d Dj

n j 1

j 1

SYY SSE SSR

• Remark: A natural way to interpret R2 is as the fraction of the variability in the

observed data interpreted by the model over the total variability in this data.

Multiple Linear Regression and

Time Series-based forecasting

• The model needs to be linear with respect to the parameters bi but not the

explanatory variables Xi. Hence, the factor multiplying the parameter bi can be any

function fi of the underlying explanatory variables.

• When the only explanatory variable is just the time variable t, the resulting multiple

linear regression model essentially supports time-series analysis.

• The above approach for time-series analysis enables the study of more complex

dependencies on time than those addressed by the moving average and exponential

smoothing models.

• The integration of a new observation in multiple linear regression models is much

more cumbersome than the updating performed by the moving average and

exponential smoothing models (although there is an incremental linear regression

model that alleviates this problem).

Confidence Intervals

• Given a random variable X and p(0,1), a p100% confidence

interval (CI) for it is an interval [a,b] such that

P ( a X b) p

• Confidence intervals are used in:

i. monitoring the performance of the applied forecasting model;

ii. adjusting an obtained forecast in order to achieve a certain

performance level

• The necessary confidence intervals are obtained by exploiting

the statistics for the forecasting error, derived in the previous

slides.

Variance estimation and the t distribution

• The variance of the forecasting error is a function of the unknown variance,

2, of the model disturbance, e.

• E.g., in the case of multiple linear regression, the variance of the forecasting

error Dˆ ( x0 ) D( x0 ) is equal to 2[1 x0T ( X T X )1 x0 ] .

• Hence, one cannot take advantage directly of the normality of the forecasting

error in order to build the sought confidence intervals.

• This problem can be circumvented by exploiting the fact that the quantity

SSE/2 follows a Chi-square distribution with n-k-1 degrees of freedom.

Then, the quantity

T

T

[ Dˆ ( x0 ) D( x0 )] 1 x0 ( X T X ) 1 x0

SSE

n k 1

2

Dˆ ( x0 ) D( x0 )

MSE [1 x0 ( X T X ) 1 x0 ]

T

follows a t distribution with n-k-1 degrees of freedom.

• For large samples, T can also be approximated by a standardized normal

distribution.

Adjusting the forecasted demand in

order to achieve a target service level p

Letting y denote the required adjustment, we essentially need to solve the following

equation:

ˆ ( x ) y) p

P ( D ( x0 ) D

0

P(

D( x0 ) Dˆ ( x0 )

MSE[1 x0 ( X T X ) 1 x0 ]

T

y

MSE[1 x0 ( X T X ) 1 x0 ]

T

y

MSE[1 x0 ( X T X ) 1 x0 ]

T

) p

t p ,nk 1

y t p ,nk 1 MSE[1 x0 ( X T X ) 1 x0 ]

T

Remark: The two-sided confidence interval that is necessary for monitoring the

model performance can be obtained through a straightforward modification of the

above reasoning.