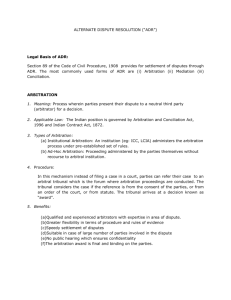

A14. A WIPO Medical Device Related Patent Arbitration

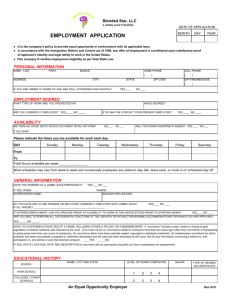

advertisement