Open Access version via Utrecht University Repository

advertisement

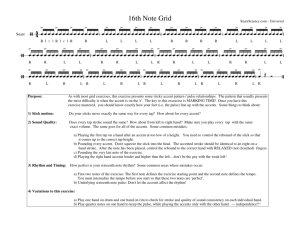

When Rah Meets Chav: Mock Accents in Contemporary British pop music. BA Thesis English Language & Culture Name: Aisha Mansaray Instructor: Koen Sebregts Date: 22/01/2013 2 When Rah Meets Chav: Mock Accents in Contemporary British Pop Music Abstract In recent years, an array of British pop artists with non-standard accents appeared on the UK music scene. While research has been done on British artists that emulated an American accent, there has been little discussion about British music and the shift in dialects from positive to negative prestige. My research focusses on artificial or mock British dialects in music and their effect on pop culture. This study involves analysis of non-standard features in three songs by different British artists who have used a fake accent. By examing cultural and sociological aspects as language, society and culture, I will create a framework on which I can base my theory. 2 Over the last 50 years, English has become the most widely used language in the world, and the increased use of English in communication has had a large impact on global culture. One of the key aspects of popular culture has been the emergence of pop music in the 1950s, which originated from the US and the UK and still has mass appeal today. An important part of popular culture is the variety of youth subcultures that are associated with the genres of pop music. Young people often form and express an identity based on genres, that is also often ascribed to their social background and surroundings (Straw, 1991, p. 370). In the UK, General American English was the dominant variety in pop music for years. Not only did American artists dominate the charts, but many British artists, such as The Beatles and The Rolling Stones, have at some point in their career adopted an American accent in their singing. However, the UK music scene changed, and new British music genres, like punk and indie-rock, were grittier than the pop music that dominated the charts and often associated with the lower classes. Especially in youth culture, an increasingly positive prestige became attributed to both regional and urban dialects often associated with lower social classes. The shift in expression of identity in British music that followed was noticeable in more British accents. This has resulted in a peculiar phenomenon: British artists incorporating a fake working class or regional accent into their music, and in doing so creating an exaggerated and sometimes artificial British working class persona. There have been a number of studies of British artists adopting a General American accent, such as that of Peter Trudgill (1982). He discusses how British bands went from emulating an American accent to returning to British over the course of the 1960’s. So far, however, there has been little discussion about the accents used in British music and the shift in dialects from American to British. 3 4 When Rah Meets Chav: Mock Accents in Contemporary British Pop Music My research focusses on artificial or mock British dialects in music and their effect on pop culture. The objective of this question is to determine what kind of identity the British bands and artists that use mock accents in their music are trying to convey. This question leads to three main questions and three sub-questions: What are the salient features that are represented in the pronunciation, and which dialect does it approach? How is the accent used different from these artists’ actual speech? What is the background of the artists who use mock accents? Which genre of music do they make and what kind of identity and subculture is usually linked to that specific genre? As the main question focuses on dialects and identity, it is interesting to see if there is a certain pattern in identity and dialects among the chosen artists that exceeds different genres of their music. Is there an identifiable common denominator? To answer these questions, I will, in the first part of this thesis, examine (social) identity, socioeconomic class and networks, and sociolinguistic aspects of society. The second part focuses on four British artists from different music genres who have at some point in their career adopted a fake or ‘mock’ British accent that is usually associated with a lower social class. By examining and comparing their normal versus their ‘mock’ accent and looking at the social and sociolinguistic conventions, my aim is to find out what identity these artists are trying to convey. 4 Theories on music and identity In order to determine how British dialects are linked to identity in British music genres and youth subcultures I will study the social and cultural theories on and descriptions of (social) identity and youth culture, to form a general idea of the content of these concepts, after which I will examine the connection between musical genres and identity. Social Identity Social identity is defined as a person’s identification in relation to others, according to what they have in common. It can be described as the portion of an individual's selfconcept derived from perceived membership in a relevant social group (Hogg and Vaughan, 2002). The highly influential social identity theory was developed by social psychologist Henri Tajfel (1974). According to sociologist Michael Hogg (2006), social identity theory is “a psychological analysis of the role of self-conception in group membership, group processes and intergroup relations”(p. 111). This theory does not serve as a general theory of social categorization as it just covers one aspect: the analysis of intergroup relations and social change as a function of positive distinctiveness. However, the social identity theory, in combination with fellow sociologist John Turner’s Self-categorization model creates the social identity approach, which has been applied to a wide variety of fields (Postmes and Branscombe, 2010). Tajfel and Turner (1979) list the essential criteria for group membership: 5 6 When Rah Meets Chav: Mock Accents in Contemporary British Pop Music applicable to large-scale social categories, and the ability of individuals to define themselves and as a member of a group. The conceptualization of a group is a collection of individuals who “perceive themselves to be members of the same social category, share some emotional involvement in this common definition of themselves, and achieve some degree of social consensus about the evaluation of their group and of their membership of it” (p. 40). Group membership is thus a tool for accommodating, or rather providing its members with self-identification in social terms. These identifications are mostly relational and comparative and define the individual as different from members of other groups. John Turner refers to self-identification on the relational level as ‘the Social Identification model’ (p. 16). This is one of the two traditional models that have been developed to investigate the dynamics of social relations, the other being the Social Cohesion model, which analyzes small, face-to-face groups instead of intergroup relations. The Social Identification model proposes, as Turner points out, that group membership has a perceptual and cognitive basis. Its subject matters are typically large-scale social categories such as nationality, sex, class, race and religion, and individuals structure the perception of themselves by comparing these social categories (self-categorization). According to Turner, the first question to determine group belonging would not be ‘Do I like these individuals?’ but: ‘Who am I? Turner then states, “What matters is how we perceive and define ourselves, and not how we feel about others” (p. 16, 22). The definition of identity I will adhere to in this study is Turner’s Social Identification model, thus a person’s self-identification by evaluating others. 6 Social structure and sociolinguistic differences in Britain As this study focuses on Britain, I will limit myself to on British social and cultural groups in youth subcultures and associated music genres. Important aspects of youth subcultures are class, gender, ethnicity and morality (Brake, 1985). As my study focuses on working class accents, I will only discuss socio-economic class. The term class usually refers to socio-economic background, which ‘groups’ people in the same social, economic or educational status. Social class is based on models of social stratification: a set of hierarchical social categories as a means of organizing societies (Grant, 2001). In modern western societies, stratification is usually organized into three main layers: the upper, middle and lower class. To understand the structure of social class and social networks and to construct a model of sociolinguistic structure of western European countries that integrate those two, Danish ethnologist Thomas Højrup divided the population in subgroups, which he called life-modes (1983). An important term in his theory is ‘network’, which refers to how a person’s social network is constructed (p. 22). One social network can be, for example, more extensive than another. These life modes are modes of production and consumption but also suggest a further integration of social network and class, because the different networks spring from difference in life modes of different individuals. Because the modes are structural, their cultural and ideological characteristics depend on other ‘life-modes’ in the formation of social structure. This is important because it explains why the interrelationships among life-modes and cultural practices vary in different countries, 7 8 When Rah Meets Chav: Mock Accents in Contemporary British Pop Music and how the life modes in Britain can have different variants from those in other western European countries (p. 23). The three life modes Højrup employed are life-mode 1, which is the closeknitted life-mode of the self-employed. Life-mode 2 is that of the ordinary wage earner whose main purpose is to provide an income that enables a ‘meaningful life’ during the worker’s free time. The final mode is life-mode 3, which is that of the higher professional wage earners (p. 23, 24). In Britain, subdivisions of each of the three main classes are commonly used, as the concept of social class is historically highly influential in Britain’s social structure and therefore more detailed (Harman, 2008). Besides the three main categories, the additional stratums used in Britain are the lower-middle class, the upper-middle class and, more recently identified, the underclass. While the social structure in Britain has significantly changed since the Second World War and some claim Britain is becoming increasingly classless, research has shown that the influence of social class on social status in Britain is still considerably prominent (Tak Wing and Goldthorpe, 2004). The differences in class are reinforced by stereotypes such as ‘chavs’, ‘Worcester women’ and ‘toffs’, all (mildly) derogatory terms for people from respectively the working, middle and the upper-class (O’Neill, 2011). Language and Class An important aspect of the social structure in Britain is the linguistic variation in regions across the county. Accents and dialects vary widely across Britain and are disparate even within counties and cities. Some dialects and accents have more 8 prestige than others; Received Pronunciation for example, is seen as very prestigious in England and Wales and is usually considered the standard accent of English in England, even though it is not linguistically superior to other varieties of English (Hudson, p. 337). It is likely to be the most studied and frequently described variety of spoken English in the world, even though only 2% of the British population speaks it (British Library). The extent to which a dialect is prestigious is socially determined: prestigious dialects are often linked to the upper-middle and upper class and people with higher education (Crystal). However, the attitude towards RP has changed over the last few years; RP was subject to change and began to diversify: “By the beginning of the twentieth century it was displaying a range of chiefly age-related differences. These would later be described as 'conservative' (used by the older generation), 'general' (or 'mainstream'), and 'advanced' (used by young upper-class and professional people), the latter often being judged as 'affected' by other RP speakers. It retained its upper and upper-middle social-class connotation, as a supra-regional standard, but from the 1960s it slowly came to be affected by the growth of regional identities […].” (Crystal). Also, virtually every British accent has been represented in the media in recent years, including the City, Civil service and academia. “As a result, fewer younger speakers with regional accents consider it necessary to adapt their speech to the same extent. Indeed many commentators even suggest that younger RP speakers often go to great lengths to disguise their middle-class accent by incorporating regional features into their speech.” (British Library). 9 10 When Rah Meets Chav: Mock Accents in Contemporary British Pop Music Youth culture So far, I have tried to outline some general prerequisites for my theory, constructed to take account of identity and social structures in Britain. In the next chapter, I will discuss British youth and music culture and by doing so, I hope to answer my main question: what kind of identity are British artists that use fake, regional accents, trying to convey? Youth culture is, as the name implies, culture that is specific to adolescents. Culture is a broad concept, but for my thesis I will regard culture based on the definition in the Oxford Dictionary: the human capacity of classification and representation of experiences with symbols, and people sharing, maintaining and transforming symbolic systems and processes like language and customs. Elements of culture include beliefs, norms, values and behavior, and in youth culture, there is an emphasis on music, sports, and an often distinctive use of language, that sets adolescents that are part of this culture apart from other age groups (Fasick,1984 p. 151). Within youth culture, there are several youth subcultures, which often attribute to adolescents a certain social identity. In the early 1950’s, the British skiffle scene grew out of the 1940’s jazz scene and became a critical stepping stone for other important British music movements like the second British folk revival and the British invasion (Brocken, 2003, p. 69). During the late 50’s to early 60’s, the rebellious image of rock and roll and blues grew popular amongst the British youth, resulting in the Mersey beat, Mod and Rocker scenes (O’Sullivan, 1974, p. 39). Since then, there have been various music 10 movements in the UK that have expanded into a life-style, with specific values, norms and practices. Andy Bennett (1999) discusses the connection between subcultures and structural changes in society: “Subcultures are seen to form part of an on-going working-class struggle against the socio-economic circumstances of their existence, and, as such, subcultural resistance is conceptualized in a number of different ways.” (p. 601). For instance, “the skinhead style represents ‘through the “mob” the traditional working class community as a substitution for the real decline of the latter” (p.601). While youth culture may have originally been a response against structural changes in society from the working class, the emerging element of freedom and increased spending power became an opportunity for young people of different socioeconomic groups to resist against a wider social order, and to break away from a traditional class-based identity. Thus, the norms, values and stylistic innovations of youth subcultures were not instigated by just working class youth but came from young people of all classes. However, as Bennett states, several groups, like skinheads, emulated the traditional working class community to a certain extend, by causing a stir and resist against the social order (p. 602). Therefore, several British subcultures where based on the working class ‘culture’ and enforced the youth’s solidarity with that culture (Hebdige, 1979, p.24). The central theme in the character of youth culture is finding an identity and to belong, and the former is, according to Sherry Ortner (1992), difficult for middle class teens as there are only a limited number of identities from which to choose (p. 4). Ortner argues that if the teenager is drifting towards an identity that is the opposite of that of their parents, the most salient oppositional models are very frequently 11 12 When Rah Meets Chav: Mock Accents in Contemporary British Pop Music characters and styles that are normally populated by working class kids. So, not only do they take a stance against their parents, but the also position themselves against ‘their’ class (p. 4). Another incentive for class reproduction is the globalization of culture, which according to Kellner and Kahn (2007) has been increasing over the past few decades and resulted in a ‘global youth culture’ (p. 3). Due to proliferation of global media, the corporate globalization and the global exchange of products, people, culture and identities, a new ‘information society’ has formed that can be seen as diversifying, but also homogenizing (Kellner and Kahn, 2007, p. 3). For most (western) countries, globalization means the adoption of American media and culture. Global youth are seen as actively engaging and identifying with this new culture, but others see the potential for global media to enlist youth to carry and adopt “the cultural logic of advanced capitalist states” as imperialist and ethnocentric. (Kellner and Kahn, 2007, p. 3). Paul Simpson (1999) argues that in music, globalization and homogenization of pop and rock music has led to a division of styles. “Bands […] try to carve out their identity by searching for some generic label that marks them out as different and unique” (p. 362). Also, Simpson mentions three interrelated factors in the performer’s choice of accent: tenor, field and mode. Tenor refers to the role of the artist to their audience, field is the context and the purpose of the text, and mode the way a song is performed, i.e. spoken, as a rap or sung (p. 351). The connection between many music genres and subcultures are that the norms, values, styles and interests of a subculture often match those expressed in the genre of music that is affiliated with that subculture. As Bennett (1999) suggests, 12 music and subcultures influence each other, and trends in music could easily become trends in subcultures and influence society: “Certainly, there are numerous instances of lifestyles that are intended to reflect more ‘traditional’ ways of life, notably in relation to class background. For example, British pop group Oasis and their fans promote an image, consisting of training shoes, football shirts and duffel coats, which is designed to illustrate their collective sense of working classness”(p. 608). I will look at the phenomenon of class reproduction through speech in contemporary music genres and the affiliated subcultures, by analyzing songs by artists in three genres that have this in common: indie-pop, hip-hop and indie-rock. Genres Despite the difference in sound, the genres indie and hip-hop have some similarities. For example, both have their roots in working class communities, as Becky Blanchard (1999) argues: “Today's rap music reflects its origin in the hip-hop culture of young, urban, working-class African-Americans, its roots in the African oral tradition, its function as the voice of an otherwise underrepresented group, and, as its popularity has grown, its commercialization and appropriation by the music industry”. Similarly, indie is via rock and roll rooted in blues, which originated from African American work songs and spirituals (Davis: 1995, pp. 2; Bolton: 2008). A characteristic feature of both genres is the way of producing the music, as Blanchard (1999) states: “[Hip-hop] was created by working-class AfricanAmericans, who […] took advantage of available tools--vinyl records and turntables-to invent a new form of music that both expressed and shaped the culture of black New York City youth in the 1970s”. 13 14 When Rah Meets Chav: Mock Accents in Contemporary British Pop Music Indie, deriving from “independent” refers to the DIY attitude of bands and the small and low-budget labels many indie bands are attached to. “The biggest indie labels might strike distribution deals with major corporate labels, but their decisionmaking processes remain autonomous. As such, indie rock is free to explore sounds, emotions, and lyrical subjects that don't appeal to large, mainstream audiences -profit isn't as much of a concern as personal taste (though the labels do, after all, want to stay in business)” (Allmusic). Furthermore, bands with a DIY attitude were able to experiment with different sounds and subjects, as they were not usually tied to large record companies and had a small, limited audience (Bateman, 2011; Allmusic). When the apparent working-class heroes broke free from life at the bottom of the pile, challenged the established order and exploded into popular culture (Bateman, 2011). However, a lot of the traditional music cultures changed because of the new digital technology, especially in the 2000s, when free music sharing on the Internet became possible. This made music available to anyone, everywhere, and artists were able to share and distribute their music more easily. While hip-hop music was already a mainstream genre by then, it meant that indie rock musicians could not only make music at a low expense, but also promote their music more extensively.” (Abebe, 2011). Similarly to indie music, the popularity of hip-hop continued and in hip-hop too many sub-genres appeared, such as Southern American Crunk and Snap, UK Grime and Grindie, a mix of indie and grime (Heawood, 2005; Collins, 2004). Mainstream success seemed to have a peculiar effect on these genres. Not only did artists begin to distinguish themselves by blending different music genres, but more artists seemed to use working class accents which were not always their own. This phenomenon was not new, as discussed by Trudgill (1983), who suggests that 14 the motivation to sound American started to become weaker around 1964 (p. 154). “British pop music acquired a validity of its own, and this has been reflected in linguistic behavior” (1983, p.153). Trudgill then discusses the punk/new wave bands that emerged in the late ‘70s, which introduced a conflicting motivation, since “the intended audience is British urban working-class youth” (1983, p.154). Another wave of British bands with Mockney accents appeared in the 19990s, the ‘Britpop’ era. Bands such as Blur, who were former art students, often exaggerated their accents in the same way 1960’s bands as the Rolling Stones or The Beatles did, as […] argues: “In terms of [the mockney style] association with Britpop, many consider the ‘mockney’ style of artists such as Damon Albarn, lead vocalist with Blur, to have evolved directly from 1960s groups, notably the Small Faces” (Bennett & Stratton, 2010, p.77). As mentioned before, the same ‘linguistic behavior’ came back in the early 2000s. The Arctic Monkeys may be the most notable example of the new wave of British artists, being one of the first British independent bands to publish and promote their music by the Internet, and achieving huge success with their first album in 2006 (Beal, 2009, p. 224). Lead singer Alex Turner’s dialect was frequently commented on in the press: “ [t]he idea of When The Sun Goes Down topping the charts appears a deeply improbable scenario: the biggest selling single in Britain might soon be a witty, poignant song about prostitution in the Neepsend district in Sheffield, sung in a broad South Yorkshire accent. As Alex Petriedis argues: “You don’t need to be an expert in pop history to realize that this is a remarkable state of affairs” (as cited in Beal, 2009). The Arctic Monkeys success led the press to mark October 2005 as the dawn of a new era in British popular music: “the simple fact that the Internet allows a 15 16 When Rah Meets Chav: Mock Accents in Contemporary British Pop Music fledging band’s music to be heard without label assistance has heralded a joyous new musical socialism (as cited in Beal, 2009, p. 224). Around that time, more artists with regional accents became popular, like The Streets, The View, Lily Allen and the Kaiser Chiefs. In the British music scene, regional accents seemed to become prestige accents. “[It] express[ed] some kind of solidarity between themselves and a historically underprivileged sector of society. It’s partly a marketing gimmick, but it’s also kind of a compliment, a way of valuing working-class experiences and lifestyle” (Bessner, 2012). Besides solidarity with the working class, it expresses solidarity with the original independent, underground nature of the genres, and it has become a way for young artists to distinguish themselves from the globalized mass culture. 16 Study Before I start with analyzing the artists’ performances, I will give a brief summary of my findings on the reason for class reproduction in music. In the 1950s, youth culture in Britain developed into an established part of society. The freedom youth culture offered to young people enabled them to take a stance against their parent and structural changes in society. Although it gave British youth in all socio-economic groups the opportunity to resist against a wider social order, several subcultures where based on the working class traditions. The subcultures emulated the traditional working class community ‘through the ‘mob’, as Bennett (1999) argues, which refers to “the [recreation] of the traditional working class community as a substitution for the real decline of the latter”. There are three other reasons for class reproduction, in music and youth subcultures. Firstly, as Ortner (1992) argues, teens in higher socio-economic groups often rebel by drifting towards an identity that is the opposite of their parents. This leads them to position themselves as ‘working class’. Secondly, the globalization of culture in the last few decades – in which pop culture has become more homogenized – often leads to the creation of a distinguishable identity through speech. In several subcultures this appears as class reproduction in speech, or in other words, taking on a working class accent. Also, the digital revolution in the 2000s has played a role in the popularization and diversification of music genres. With the Internet as their medium, artists are able to distribute their music for free, and new – often hybrid –music styles have gained 17 18 When Rah Meets Chav: Mock Accents in Contemporary British Pop Music popularity by the Internet. As a result, artists distinguish themselves by using nonstandard features in their accent. Finally, Simpson argues that three important factors in the choice of accent of artists are tenor, field and mode, and they should be placed into a wider, social and cultural context to understand why a performer would choose a particular accent. Class reproduction is seen in both music and youth subcultures, and they influence each other: subcultures reflect more ‘traditional’ ways of life and similarly, the themes in music are about life and society. For my study, I have chosen three British, contemporary artists in different genres that use, or have used a working class accent in their music that is not their own. These are, respectively, Kate Nash, who makes indie-pop, rapper Professor Green and indie rock band The Kooks. I chose these particular artists because they are all notable British artists, their first albums met with positive critical and commercial receptions, and because all three artists released their first albums in 2006, around the time of the Arctic Monkeys first release and the popularization of working class accents in music (NME). Also, they all appeared in the music scene at roughly the same time, which might explain this phenomenon. I will analyze the following features in a song of all three artists, and then pick either another song or a recording that features their normal speech. By comparing these two accents I will be able to see whether the accent in the song is exaggerated, or even fake. Because it is not always clear in which category the vowels and consonants fall as the artists sometimes mix dialects, I have used RP to compare accents. Although I do not see this as an accent that is better or more prestigious than other accents and dialects, it is a variety of spoken English that is widely known and often 18 used for teaching English as a foreign language. With RP as a measurement, it is easier to identify a regional or lower prestige variety. Kate Nash Kate Nash is a singer and songwriter from Harrow, London. In 2005, she uploaded her music onto MySpace, after which she signed to the independent, London-based record label Moshi Moshi records and released her first single, “Caroline is a victim” (Kate Nash Official Website). Her Cockney accent stood out, and fitted in with the wave of British artists singing with mock dialects. Despite being called ‘chav’ in the press because of her accent, she claims being “brought up well” by her family and is “way too articulate for a chav” (Colothan, 2007). In Nash’s second single “Foundations”1, many phonetic features in her singing are typical of Cockney, as shown in Table 1 and 2. Many of her vowels are lowered, the RP /aɪ/ in ‘price’ for instance becomes [ɑɪ], and /ei/ in ‘face’ changes into [æɪ]. Furthermore, the final –er in words like ‘fitter’, ‘bitter’ are pronounced with the broad Cockney lowered [ɐ] (Hughes and Trudgill, 1979, p. 41). Another prominent feature is the use of [aʊ] in words like ‘go’ and ‘know’, which is also a Cockney variant (Hughes and Trudgill, 1979 p, 41). The consonants are also typical for the Cockney accent: there is distinctive Tglottalization in almost every word with an intervocalic and final ‘t’, like ‘got’ and ‘humiliate’, Th-fronting in ‘rather’ and ‘with’, G-dropping of most words that end with /ɪŋ/ (Hughes and Trudgill,1979 p, 41). Furthermore, Nash vocalizes the dark /l/ in ‘call’ and uses R-labialization; [ʋ] instead of /r/ in ‘aggressive’ and ‘boring’. 1 Appendix A. 19 20 When Rah Meets Chav: Mock Accents in Contemporary British Pop Music However, Nash does not use any Cockney grammar, and besides the word ‘trainers’ (which is general British English) there are no specifically Cockney words in “Foundations”. Also, her accent is not very consistent; in “Foundations” for example, the final –er in ‘bitter’ becomes a lower [ɐ], but the /t/ is still pronounced as [t] instead of [ʔ]. Nash’s accent in spoken language is notably different than that used in “Foundations”, as shown in Table 3 and 4, based on an interview from 20102. The pronunciation of the diphthong /əʊ/, which she in Foundations realized as [aʊ], becomes an [əʊ]. The lower [ɐ] for the final –er is now [ə], which is the RP variant. All consonants seem to have changed to the RP variant, with the exception of one sentence, in which Nash pronounces ‘that’ twice, and the final /t/ switches from /t/ to /ʔ/. 2 Appendix B 20 Table 1 Non-standard vowel variants, after Hughes and Trudgill,1979. Keyword FACE KNOW AGO PRICE RP variant [ei] [əʊ] [ə] [aɪ] Cockney Variant in “Foundations” [æɪ] face, pasty, wasted [aʊ] won’t, go, holding, know [ɐ] bitter, fitter, [ɑɪ] night, I, my, fine, eye, time, smile, surpise, childish, Table 2 Non-standard Consonant Variants after Hughes and Trudgill,1979. Consonant /t/ RP variant [t] Variant in “Foundations” [ʔ] got, it, humiliate, front, bit, fight, right, upset /ŋ/ [ŋ] /ɹ/ [ɹ] /θ/ [θ] [f] with /ɫ/ [ɫ] [ʊ] call [n] Tellin, holdin, makin, morning [ʋ] Aggressive, boring 21 22 When Rah Meets Chav: Mock Accents in Contemporary British Pop Music Table 3 Standard vowel variants after Hughes and Trudgill,1979 Keyword RP variant Variant in Interview FACE [ei] [ei] plane, day KNOW [əʊ] [əʊ] video, know AGO [ə] PRICE [aɪ] [ə] sister, photographer [aɪ] like, signs, my Table 4 standard consonant variants after Hughes and Trudgill,1979 Consonant RP variant Variant in Interview /t/ [t] [t] knitted /t/ [t] /ŋ/ [ŋ] [ŋ] amazing /θ/ [θ] [θ] with /ɫ/ [ɫ] [ɫ] fall [ʔ] title, negative, that 22 Professor Green Stephen Manderson, a.k.a Professor Green was born in Hackney, and raised in EastLondon by his grandmother and uncles. His childhood was not particularly carefree, as he had no stable family life and grew up in a rough part of Hackney, where he became a drug dealer (McLean, 2012; Swash, 2010). Like Kate Nash, Professor Green rose to success via MySpace, on which he entered and won a rap contest twice. He released his first mix-tape in 2006, and his first full album in 2010, on fellow London rapper The Streets’ label (Swash). On “Into the Ground”, 3 4 Professor Green’s accent seems highly influenced by Cockney and Multicultural London English (MLE) in his songs, while the latter is not as clearly present in his normal speech. 5 MLE is a relatively young dialect, and a “blend of West Indian English, East Indian English, and some other things as well, all grafted onto a Cockney and/or Estuary-English substrate” (Liberman 2006). Although MLE is often associated with Britons of Caribbean descent, it is spoken by innercity Londoners of many ethnicities. Salient features are, according to Torgersen et al (2007), monopthongization of /aɪ/ in price (to /a/) which is the opposite of Cockney, but very close to a Jamaican accent. The vowel /ei/ is also monophongized, to [e:]. The vowel in goose, you and food is pronounced with a central or nearly front vowel. Furthermore, salient features of MLE are H-dropping, DH-stopping (using [d] for word-initial /ð/) and TH-fronting: using [f] for /θ/ (Torgersen et al, 2007). In the song, the rapper uses advanced /uː/ fronting, so that it becomes an [ʏː], which is a salient MLE feature (Torgersen et al, 2007). Another salient feature of Appendix C The (rather unfriendly) lyrics in this song are about Kate Nash: http://www.nme.com/news/professor-green/58362 5 Table 5 and 6. 3 4 23 24 When Rah Meets Chav: Mock Accents in Contemporary British Pop Music MLE in the song is the monophtongization of /aɪ/, pronounced with a low-back onset, which becomes a lowered, unrounded sound close to /a/. The diphthong /eɪ/ also becomes a monophtong,[e:] in pray and day, also a feature in MLE. Also, the Cockney variant [ɐ] is used as –er in another and brother, and the diphthong /əʊ/ is lowered and monophtongized to [ɔː]. Professor Green’s consonants also match MLE (and Cockney, as there are similarities in the salient features). Almost every /t/ is replaced with a glottal stop. Furthermore, there is G-dropping, L-vocalization and lastly, DH-dropping, a salient feature of MLE, is also used in words like with and this, which become [wɪd] and [dɪs] (Torgensen et al, 2007). In contrast to Kate Nash, Professor Green uses grammar and lexicon that are typical for the Cockney dialect. Professor Green uses Imma (I am going to), which is often used in AAVE, and the negation ain’t, which is used in many English dialects, including AAVE, but also MLE and Cockney (Hargraves, 2011; Hughes and Trudgill, 1996; Wells 1982b). Professor Green uses words like shagging and minge, which are general British English slang. Other slang terms, such as dimwit, prick and dipstick (foolish, inconsiderate or stupid person) vajazzle (genital decoration), in a muddle (confused), cop a feel (touching someone without permission), long in the tooth (being very old), call my bluff (to announce), are not necessarily British, or MLE. The only word that could fall under the category of MLE is rah, which probably comes from the Jamaican word rhaatid: a mild expletive of surprise or vexation (Patois Dictionary). A ‘rah’ is also a British pejorative term for a young, affluent person, but the first meaning fits into the context of the sentence: “back, intact and I’m still pro, rah!” (Meltzer, 2010). 24 In the interview6, the features of the MLE accent are not present; instead, Professor Green mostly talks in a Cockney dialect. The vowels /ə/, /uː/ and /aɪ/ are realized as their RP variant, so they are pronounced as the transcription suggests. Professor Green uses the RP /eɪ/ for away and same, but late is pronounced with a more open, Cockney vowel: [æɪ]. In words with a GOAT vowel, he switches between the RP [əʊ] and the Cockney [aʊ]. Another Cockney feature is the raising of /ʌ/ to [a] in ‘bumped’ (Wells, 1982b, p. 23). The realization of consonants has changed too: there is no DH-dropping, instead, the /θ/ in ‘with’ is pronounced with a glottal stop, as are most of the /t/’s. Furthermore, /ð/ in either is pronounced as [v], and there is still G-dropping in –ing words: morning, standing. Table 5 Standard vowel variants after Torgensen et. al, 2007). Keyword RP variant Variant in “Into the Ground” GOOSE [uː] [ʏː] dilute, look, full FACE [eɪ] [e:] pray, day AGO [ə] PRICE [aɪ] [a] light, wife, like GOAT [əʊ] [ɔː] Don’t 6 [ɐ] another, brother Appendix 4, Table 7 and 8. 25 26 When Rah Meets Chav: Mock Accents in Contemporary British Pop Music Table 6 Standard Consonant variants after Torgensen et al, 2007). Consonant RP variant Variant in “Into the ground” /θ/ [θ] [d] with /ð/ [ð] [d] this /t/ [t] [ʔ] water, courting, got /ŋ/ [ŋ] [n] courting, talking, walking /ɫ/ [ɫ] [ʊ] call, muddle Table 7 Standard vowel variants after Hughes and Trudgill,1979. Keyword RP variant Variant in interview GOOSE [uː] [uː] full FACE [eɪ] [eɪ ~ æɪ] away, same, late AGO [ə] [ə] burger, dissapear PRICE [aɪ] [aɪ] nights, trying GOAT [əʊ] [əʊ ~ aʊ] so, ago STRUT [ʌ] [a] bumped Table 8 Standard Consonants variants after Hughes and Trudgill,1979. Consonant RP variant /θ/ [θ] /t/ [t] /ð/ [ð] /ŋ/ [ŋ] Variant in interview [ʔ] with [ʔ] pretty, night, little [v] either [n] morning, standing 26 The Kooks The Kooks are a British Indie rock band from Brighton, England. The band consists of 4 members of which Luke Pritchard is the main singer (The Kooks Official Website). After they met in 2002 at the Brighton Institute of Modern Music they formed a band in 2004, inspired by artists such as The Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan and David Bowie (Stanley, 2006). After releasing an EP demo and playing several concerts, they signed with Virgin Records (Billboard). Their first album, Inside In/Inside Out, came out in 2006 and reached No. 2 in the British Music charts (Billboard). In the media, The Kooks are often referred to as a ‘posh’ band, most members having attended private schools (Heawood, 2008). In “Ooh La”7, a song on Inside In/Inside Out, singer Luke Pritchard seems to be singing in an undefined Northern British accent. Especially the vowels are pronounced in Northern English. One well-known Northern English feature is the absence of the foot-strut split, which means that for instance cut and put are both pronounced with [ʊ] (Wells, 1982, p. 57). This is notable in Pritchard’s voice, in ‘discovered’ for example, where the [ʌ] is realized as [ʊ]. Also generally there is no trap-bath split in Northern English varieties. The /ɑː/ is absent, so cat and bath, and as Pritchard says, ‘can’, ‘man’ and ‘spat’ are pronounced with [a] (Wells, 1982, p.317). Additionally, Happy-tensing occurs in money, and her is pronounced with [ɛː], which is a Scouse feature (Wells, 1982, p.317). In “Ooh La”, there are not many salient features in the pronunciation of consonants. The omission of /t/, as well as the pronunciation of /t/ as the fricative [s] 7 Appendix 5 27 28 When Rah Meets Chav: Mock Accents in Contemporary British Pop Music are both features of Northern English; the first is a salient feature of the Yorkshire dialect, while the latter is present in the Scouse dialect (Wells, 1982b, p. 317). In the interview with Luke Pritchard8, the strut-foot split is present, as the vowels in stuff, up and us are all pronounced [ʌ]. While and I are pronounced [ɒɪ], which is a Cockney variant (Wells 1982b, 308, 310). The Trap and Goose vowels are pronounced as in RP, and there is no occurrence of Happy tensing. Most of Pritchard’s final and intervocalic /t/’s are glottalized. The [ɹ] in very is realized in the Cockney variant [w], and there are occurrences of G-dropping and dark l vocalization, also both salient features of the Cockney dialect. As in Kate Nash’s “Foundations”, there are no specific occurrences of exclusive lexicon or grammar, but the use of ‘petticoat’ could refer to the 1950s, and by using this in combination with the sentence ‘Go to Hollywood’ and the genre of the song, The Kooks may have wanted to ‘imitate’ a working class persona in the style of 50’s rock and roll bands, contrasted by the glamour of the girl with the petticoat who wants to go to Hollywood. 8 Appendix 6 28 Table 9 Standard vowel variants after Hughes and Trudgill,1979 Keyword STRUT RP variant [ʌ] Variant in “Ooh La” [ʊ] discovered, such, understand TRAP [æ] [a] can, spat, understand HAPPY [i:] [ɪ] money FUR [ɜː] [ɛː] her Table 10 Standard Consonants variants after Hughes and Trudgill,1979 Consonant RP variant Variant in “Ooh La” /t/ [t] [ʔ] that /t/ [t] omission of /t/ find, petticoat, chewed /t/ [t] [s] out Table 11 Standard vowel variants after Hughes and Trudgill,1979. Keyword RP variant Variant in interview STRUT [ʌ] [ʌ] stuff, up, us PRICE [aɪ] [ɒɪ] while, I TRAP [æ] [æ] band HAPPY [i:] [i:] really, very GOOSE [u:] [ʊu] room 29 30 When Rah Meets Chav: Mock Accents in Contemporary British Pop Music Table 12 Standard Consonants variants after Hughes and Trudgill,1979. Consonant RP variant Variant in interview /t/ [t] [ʔ] got, it, but, spot /ɹ/ [ɹ] [w] very /ŋ/ [ŋ] [n] doing, recording /ɫ/ [ɫ] [ʊ] halls, difficult 30 The next tables show the percentages of standard and non-standard consonants and vowels that occur in the songs and interviews. The total number of vowels and consonants refer to the ones discussed in the tables above. The percentage of non-standard vowels and consonants in the Kooks’ “Ooh La” is, compared to the percentage in the two other songs, very low. The reason for this could be that compared to Kate Nash and Professor Green, the accent Luke Pritchard is trying to convey with the non-standard pronunciation he uses in “Ooh La” is very different and far removed from his own accent. The percentage of nonstandard vowels and consonants in the interview is higher, but are close to Cockney, and not a Northern dialect, which is used in the song. This is also the case for Professor Green in the interview, which also has a high percentage of non-standard vowels and consonants, but they are predominantly cockney, and not MLE, as he uses in “Into the Ground”. Kate Nash’s interview does however show that she normally has an accent that is close to RP, instead of the Cockney accent she uses in “Foundations”. Table 13 Occurrences of Standard and Non-standard vowels and consonants in “Foundations” Keyword/Consonant Total Standard Variant Non-Standard Variant FACE 12 4 8 KNOW 22 0 22 AGO 2 0 2 PRICE 65 0 65 /t/ 54 11 43 /ŋ/ 15 2 13 /ɹ/ 3 0 3 /θ/ 9 7 2 /ɫ/ 7 6 1 Total: 189 30 159 Total percentage standard vowels and consonants: 15,8 % Total percentage non-standard vowels and consonants: 84,2 % 31 32 When Rah Meets Chav: Mock Accents in Contemporary British Pop Music Table 14 Occurrences of Standard and Non-standard vowels and consonants in interview with Kate Nash Keyword Total Standard variant 13 13 0 KNOW 5 5 0 AGO 5 5 0 PRICE 13 13 0 /t/ 12 7 5 /ŋ/ 2 2 0 /θ/ 6 6 0 /ɫ/ 3 3 0 Total: 59 54 5 FACE Non-standard variant Total percentage standard vowels and consonants: 91,5 % Total percentage non-standard vowels and consonants: 8,4 % Table 15 Occurrences of Standard and Non-standard vowels and consonants in “Into the Ground” Keyword/Consonant Total Standard Variant Non-Standard Variant GOOSE 17 9 8 AGO 5 3 2 PRICE 42 4 38 GOAT 5 2 3 /θ/ 6 3 3 /ð/ 23 0 3 /t/ 24 0 24 /ŋ/ 15 2 13 /ɫ/ 17 8 9 32 Total: 154 31 123 Total percentage standard vowels and consonants: 20,1 % Total percentage non-standard vowels and consonants: 79,9 % Table 16 Occurrences of Standard and Non-standard vowels and consonants in interview with Professor Green Keyword Total Standard variant Non-standard variant GOOSE 3 3 0 FACE 4 2 2 AGO 4 2 2 PRICE 4 1 3 GOAT 3 1 2 STRUT 3 0 3 /θ/ 5 1 4 /t/ 6 0 6 /ð/ 1 0 1 /ŋ/ 7 0 7 Total: 40 10 30 Total percentage standard vowels and consonants: 25 % Total percentage non-standard vowels and consonants: 75% Table 17 Occurrences of Standard and Non-standard vowels and consonants in “Ooh La” Keyword/Consonant Total Standard Variant Non-Standard Variant STRUT 16 10 6 TRAP 7 3 4 HAPPY 39 38 1 FUR 8 2 6 /t/ 39 29 10 Total: 109 82 27 Total percentage standard vowels and consonants: 75,2% 33 34 When Rah Meets Chav: Mock Accents in Contemporary British Pop Music Total percentage non-standard vowels and consonants: 24,8 % Table 18 Occurrences of Standard and Non-standard vowels and consonants in interview with Luke Pritchard (The Kooks) Keyword Total Standard variant Non-standard variant STRUT 7 7 0 PRICE 10 4 6 TRAP 8 8 0 HAPPY 5 5 0 GOOSE 4 3 1 /t/ 17 5 12 /ɹ/ 11 9 2 /ŋ/ 4 3 1 /ɫ/ 3 2 1 Total: 69 46 23 Total percentage standard vowels and consonants: 66,6 % Total percentage non-standard vowels and consonants: 33,3 % Conclusion 34 In this study, I have discussed three artists that use a mock dialect in their songs. All three artists released their first albums in 2006, which was the time more artists with low prestige accents appeared on the UK music scene. The theory of tenor, field and mode as discourse for the choice of accent applies here; Kate Nash’s tenor is coming of age as a female, vulnerability and dealing with relationships. Her lyrics are relatable for many young women, which is why a low prestige accent could be perceived as easily accessible. The field, or the content and purpose of the text, is the dying relationship between boy and girl, and the everyday irritations and arguments. The mode of “Foundations” is partly sung, partly rhythmically spoken. This gives it a narrative tone, as if you are being told a story. The tenor, field and mode of “Foundations” frame Kate Nash as a common persona, someone that experiences things many females of that age can relate to. This could very well be a factor in her choice of accent. Professor Green’s tenor is – like Kate Nash’s tenor – gender expression, a magnified expression of masculinity by angrily mocking people (field) and thereby creating a ‘tough’ image. “Into the Ground” is pointed at other young males, and by rapping (mode) and using a multicultural London accent: his persona is that of a young, under-privileged male on the street. On “Ooh La”, The Kooks’ tenor is creating a working class persona by composing the field: a contrast between a glamorous girl and the ‘narrator’ in the ‘frame’ of a rock and roll song, thereby taking on an accent (their mode) reminiscent of rock and roll bands such as The Rolling Stones and The Beatles. The three interrelated factors I discussed above need to be taken into account, but also globalization, and a wider sociopolitical and cultural context. 35 36 When Rah Meets Chav: Mock Accents in Contemporary British Pop Music Globalization and the resulting homogeneity of pop and rock music has led to a fragmentation of styles, in which bands try to carve out an identity and to be different and unique. British Artists such as Kate Nash and The Kooks are marketed as indie in a time where the digital revolution had allowed indie bands to achieve mainstream success. The Arctic Monkeys (following British bands in the 1960s1990s) stood out, with their strong, working class accent. This could have opened the door for other contemporary artists to set themselves apart from the crowd by using a non-standard, low prestige accent, at the time of globalization and dominant American accents in music. Not only would they be ‘unique’ (if they are still unique, in a music scene where working class accents are a trend), but also show solidarity with the social values that are associated with the origins of the indie genre. Professor Green, despite making a different genre of music, shows the same solidarity with the social values that are attached to the hip-hop subculture. But unlike Kate Nash and The Kooks, who have a fairly well-behaved image, artists with a ‘rough’ image such as Professor Green may have a slightly different reason for using a mock accent. As Andy Bennett argues, subcultures form part of a working class struggle against the socio-economic circumstances of their existence. The skinhead style for example, represents the traditional working class community ‘through the mob’. Professor Green expresses, like many artists in the punk genre, his anger in his music, thereby creating an image many young men in London can identify with. This seems to correlate with Ortner’s notion that young people, in taking a stance against their parents and structural changes in society, position themselves against their class. Ortner argues that if the teenager is drifting towards an identity that is the opposite of that of their parents, the working class ‘identity’ is the most salient, oppositional model. What I think that also plays a role is the fact that the 36 middle class identity is hard to define. As mentioned earlier, forming an identity is difficult for middle class teens, as there are only a limited number of identities from which to choose. Thus, the middle class identity is quite limited in its ‘broadness’. Music is an important factor in youth culture, just as youth culture has become an important part of society. Social identity plays a big part in youth culture, as adolescence is a phase in life wherein many people find – or try to find – their identity, and group membership, according to Tajfel and Turner, is a tool for providing its members with self-identification in social terms. Individuals structure the perception of themselves by comparing social categories, in this case youth subcultures. Music, as common interest, connects these groups. Mock accents in UK pop music are not new and seem to return every decade. However, globalization is a new phenomenon, which I think plays a major role in the recent change amongst youth: the acceptance of regional accents, and sometimes even the incorporation of regional dialect features in RP. The reason for this is, as I mentioned before, most likely because of the need to diversify in a globalized (or McDonaldized) world, where culture is increasingly homogenized. While RP is diversifying and the acceptance of regional varieties of British English has grown, the influence of artists with working class accents on youth subculture could play a major role in the way dialects and accents in Britain develop. 37 38 When Rah Meets Chav: Mock Accents in Contemporary British Pop Music References Abebe, N. (2010, February 25). The decade in indie. Pitchfork, Retrieved from: http://pitchfork.com/features/articles/7704-the-decade-in-indie/ Allmusic. (2011). Indie Rock. Retrieved from: http://www.allmusic.com/style/indie-rock-ma0000004453 Bateman, Tom. (2011, January 28). Has pop gone posh? BBC News. Retrieved from: http://news.bbc.co.uk/today/hi/today/newsid_9373000/9373158.stm Beal, J. (2009). “You’re Not from New York City, You’re from Rotherham” Journal of English Linguistics, 37(3), 224. Retrieved from: http://eng.sagepub.com.proxy.library.uu.nl/content/37/3/223.full.pdf+html Bennett, A. (1999). Subcultures or Neo-Tribes?: Rethinking the Relationship Between Youth, Style, and Musical Taste? Sociology, 33(3), 601-608. Bennett, A., Stratton, J. Britpop and the English music tradition (pp. 77). London: Ashgate Publising Unlimited. Besner, L. (2012, December, 12). On Mick Jagger, mockney accents, and being a chav. Hazlitt. Retrieved from: http://www.randomhouse.ca/hazlitt/feature/mick-jagger-mockney-accentsand-being-chav Billboard. Retrieved from: http://www.billboard.com/artist/the-kooks/717758#/news/thekooks-1003540374.story Blanchard, B. (1999). The Social Significance of Rap and Hip-Hop Culture. Media and Race. Paper. Retrieved from: http://www.stanford.edu/class/e297c/poverty_prejudice/mediarace/socialsignif icance.htm Bolton, M. (2008, October 3). Class war on the dance floor. The Guardian. Retrieved from: http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/2008/oct/03/popandrock.foals Brake, M. (1985) Comparative Youth Culture: The sociology of youth culture and youth subcultures in America, Britain and Canada, Routledge, New York Brocken, M. (2003). The British folk revival, 1944–2002. (pp. 69). Aldershot: Ashgate. Collins, H. (2004, November 19). Will grime pay? BBC Collective. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.co.uk/dna/collective/A3299204 Colothan, S. (2007, September 26). Kate Nash: “I’m the new Posh Spice”. Retrieved from: http://www.gigwise.com/news/37305/kate-nash-im-the-new-posh-spice Davis, F. (1995). The History of the Blues. (pp. 2). New York: Hyperion. 38 Fasick, A. Frank (1984). “Parents, Peers, Youth Culture and Autonomy in Adolescence”. Adolescence, (73)3, 151. Grant, J. Andrew (2001). Definition of Class. In Jones, R.J. Barry. Routledge Encyclopedia of International Political Economy: Entries A-F (pp. 161). London: Taylor & Francis. Hargraves, O. (2011, November 1). I Dig You Rap. Macmillan Dictionary Blog. Retrieved from: http://www.macmillandictionaryblog.com/i-dig-your-rap Heawood, S. (2006, May 5). When hood meets fringe. The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/2006/may/05/popandrock Heawood, S. (2008, April 4). “I am a hit machine…I just roll ‘em out”. The Guardian. Retrieved from: http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/2008/apr/04/popandrock1 Hebdige, D. (1979). Subculture: The Meaning of Style. (pp. 24). London: Routledge. Hogg, M. A. (2006). Social identity theory. In P. J. Burke (Eds.), Contemporary social psychological theories (pp. 111-112). Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press. Hogg, M.A., & Vaughan, G.M. (2002) Social Psychology. 1st ed. California: Prentice Hall. Højrup, T. (1983) On the Concept of life-Mode. A Formspecifying Mode of Analysis Applied to Contemporary Western Europe. Ethnologia Scandinavica, 3, 22. Kate Nash Interview. (MTV). (2010, March 11). The 5. [Video File]. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7kMZYUYYVx8 Kellner, D. (1989). Critical Theory, Marxism, and Modernity. (pp. 3). Cambridge: Polity Press McLean, C. (2012, May 27). It’s Not Easy being Professor Green: the rapper, the heiress and the drama Made in Chelsea. The Independent. Retrieved From: http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/music/features/its-not-easybeing-professor-green-the-rapper-the-heiress-and-a-drama-made-in-chelsea7782415.html Meltzer, T. (2010, March 28). The gap year that went viral. The Guardian. Retrieved from: http://www.guardian.co.uk/technology/2010/mar/28/gap-year-spoof-youtube New Music Express (NME). (2007, January,16). Lily Allen, Muse head list of BRIT Award nominations. Retrieved from: http://www.nme.com/news/muse/25876 O'Sullivan, D. (1974) The Youth Culture. (pp. 39). London: Taylor & Francis. Ortner, S. (1992). Resistance and Class Reproduction Among Middle Class Youth. (Working Paper No. 71). (pp. 4). Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan. Oxford Dictionary. Retrieved from: http://oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/culture 39 40 When Rah Meets Chav: Mock Accents in Contemporary British Pop Music Patois Dictionary. (2008). Retrieved from: http://niceup.com/patois.html Postmes, T. & Branscombe, N. (2010). Sources of social identity. In T. Postmes & N. Branscombe (Eds), Rediscovering Social Identity: Core Sources. Psychology Press. Professor Green Interview. (Shakedown Festival). (2012, October 19). Professor Green at Shakedown Festival. [Video File]. Retrieved from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8qvXwBFo6JI Simpson, Paul. (1999). Language, Culture and Identity: with (another) Look at Accents in Pop and Rock Singing. Multilingua, 18(4), 351-362. Stanley, K. (2006, August 16). The Kooks come to the Farm. BBC local Lincolnshire. Retrieved from: http://www.bbc.co.uk/lincolnshire/content/articles/2006/08/15/the_kooks_prev iew_feature.shtml Straw, W. (1991). System of Articulation, Logics of Change: Communities and Acenes in Popular Music. Cultural Studies, 5(3), 273. Swash, R. (2010, April 20). How Professor Green gatecrashed the charts. The Guardian. Retrieved from: http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/musicblog/2010/apr/20/professorgreen-need-you-tonight Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 40). Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole Tajfel, H. (1982). Social Identity and Intergroup Relations. (pp. 16, 22, 26) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. The Kooks Interview. (OffGuardGigs). (2011, November 21). Exclusive Interview for OFF GUARD GIGS). [Video File]. Retrieved from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mbg2sk0B0z8 The Kooks Official Website. The Kooks – Biography. Retrieved from: http://www.thekooks.com Torgersen et. al. (2007). Phonological Innovation in London Teenage Speech. 4th Conference on Language Variation in Europe. Lancaster University. Trudgill, P. (1983). On Dialect: Social and Geographical Perspectives. 2nd ed. (pp. 153-155). New York: New York University Press. Wells, J.C. (1982b). Accents of English. (pp. 308, 310, 317) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Appendix A Kate Nash – Foundations 40 Thursday night, everything's fine, except you've got that look in your eye when I'm tellin' a story and you find it boring, you're thinking of something to say. You'll go along with it then drop it and humiliate me in front of our friends. Then I'll use that voice that you find annoyin' and say something like "yeah, intelligent input, darlin', why don't you just have another beer then?" Then you'll call me a bitch and everyone we're with will be embarrassed, and I wont give a shit. My fingertips are holding onto the cracks in our foundation, and I know that I should let go, but I can't. And every time we fight I know it's not right, every time that you're upset and I smile. I know I should forget, but I can't. You said I must eat so many lemons 'cause I am so bitter. I said "I'd rather be with your friends mate 'cause they are much fitter." Yes, it was childish and you got aggressive, and I must admit that I was a bit scared, but it gives me thrills to wind you up. Your face is pasty 'cause you've gone and got so wasted, what a surprise. Don't want to look at your face 'cause it's makin' me sick. You've gone and got sick on my trainers, I only got these yesterday. Oh, my gosh, I cannot be bothered with this. Well, I'll leave you there 'till the mornin', and I purposely wont turn the heating on and dear God, I hope I'm not stuck with this one. Appendix B Kate Nash Interview (2010) 41 42 When Rah Meets Chav: Mock Accents in Contemporary British Pop Music - “I shot the video for it on a plane…” 9 - “…doing dance routines with like the exit signs, like this…”10 - “…and there’s this other girl he is going out with…” 11 - “…and then me and the wholesome guy fall together, and then: are we going to kiss…I don’t know, you’ll never find out.” - “…my sister, Clare Nash, she is a photographer and we’ve done a lot of work together over the past year…”12 - “…so there’s like amazing pieces…”13 - “…a really cool, long black and white striped dress with knitted cuffs…” 14 - “It basically means that…I had another title for the album, which was like the negative version of that…”15 - “…and every day is quite hard, and not very pretty or romantic…”16 Appendix C Professor Green – Into the ground 0.22-0.26 0.45-0.48 11 0.55-0.58 12 1.21-1.28 13 1.53-2.00 14 2.07-2.13 15 2.39-2.43 16 4.01-4.06 9 10 42 Before I'm done Imma run this, run this. Before I'm done Imma run this, run this. Before I'm done I'm a run this town. Into the ground. Dilute me, water me down, how? There's more chance of me courting a cow disappeared, last seen walking around At 27 with a sign saying 40 and proud Does Katie look like Amy, or Amy look like Katie? What the fuck are these cosmetic surgeons creating? I'd never imagined shagging a mannequin But that vajazzle is, so bedazzling I want the light skinned chick from the misfits To pull my pants down and tell me if this fits When I say I'm a big prick; it's my dick talking I can't help it, I'm a bit of a dipstick Sadistic, come on cunts! insult me I insist A dimwit with a dick covered in lipstick on the prowl, walking around zipper down; dick sticking out! Who wants to fuck with me now? A half wit with a fringe started it an he's stuck with me now! I'm hunting him down Wow, how could he accuse me of clucking over crusty the clown? You're in trouble, prick, I'm in a muddle, prick Prick, is that your chick or Mick Hucknell, prick Dick, minge you puss I pray for the day I find him face down in that ginger bush Imagine cheating on your wife Footballers are as sleazy as you like Imagine sleeping with the wife of another Imagine sleeping with the wife of your brother Imagine if I said Imogen, I may do If I hate you, for me to name an shame you ain't nothing Make a mistake and say something, nothing Not even an injunction with a cape could save you I don't say this to all the girls just you, because I trust you, come here slut I need a drug mule I do these things because its fun to I don't need a mule for drugs I just wanted to see if you were in love enough to put drugs up you? Now you've got a clung full of monk and mushrooms I really can't believe you called my bluff I ain't fingering your chick I'm looking for my drugs Why think about what I say? I say what I feel Women call me rapey, I say cop a feel 43 44 When Rah Meets Chav: Mock Accents in Contemporary British Pop Music The worst day on this earth was the day I got a deal I ain't been the same since the day I dropped a pill I ain't lost appeal I got appeal though Spit hard kick rhymes with a steel toe Cap, been bad with a real flow Back, intact and I'm still pro, rah! Your opinions ain't shit to me I couldn't give a fuck what you think of me I may contradict myself as I change and I grow Though my bet'd be I'll be this way till I'm old From I was young I've been too long in the tooth I ain't down with the trumpets I ain't quirky or cool If I've offended you and you're coming to get me? Just know if I'm going to hell you're coming with me Appendix D Professor Green interview 2012 44 - “We’re practically best friends now, so…” 17 - “It’s been pretty full on, and I had a couple of nights off. I went out for dinner with Example two nights ago, that ended up 5 o’clock in the morning, yesterday morning.” 18 - “…we had on of the best burgers, probably the best burger in London. It was gonna end there, but ehm, we just got a bit carried away. And then last night was pretty much the same…” 19 - “…I just saw a few heads disappear in the distance…” 20 - “…it’s not like I wasn’t trying either, I wasn’t just standing there…”21 - “…I wanna try and catch a little bit of Dizzee, who I just bumped into…”22 Appendix E The Kooks – Ooh La In their eyes is a place that you finally discovered 0.10-0.11 0.29-0.39 19 0.54-1.04 20 1.15-1.17 21 1.35-1.37 22 1.54-1.57 17 18 45 46 When Rah Meets Chav: Mock Accents in Contemporary British Pop Music That you love it here, you've got to stay On the bottom of the rock, an island On which you find you love it when you twitch You feel that itch in you pettycoat Your pretty pretty pettycoat Then you smiled, he got wild You didn't understand that there's money to be made Beauty is a card that must get played By organisation And ooh la, she was such a good girl to me And ooh la, the world just chewed her up and spat her out And ooh la, she was such a good girl to me And ooh la, the world just chewed her up and spat her out The world can be a very big place So be yourself don't get out of place Love your man and love him twice Go to Hollywood and pay the price Oh go to Hollywood And don't be a star, it's such a drag Take care of yourself, don't begin to lag It's a hard life to live, so live it well I'll be your friend and not in pretend I know you girl In all situations And ooh la, she was such a good girl to me And ooh la, the world just chewed her up and spat her out And ooh la, she was such a good girl to me And ooh la, the world just chewed her up and spat her out Pretty pretty pretty pretty pretty pretty pretty pretty pretty Pretty pretty pettycoat Pretty pretty pretty pretty pretty pretty pretty pretty pretty Pretty pretty pretty pretty pretty pretty pretty pettycoat In all situations And ooh la, she was such a good girl to me And ooh la, the world just chewed her up and spat her out And ooh la, she was such a good girl to me And ooh la, the world just chewed her up and spat her out Appendix F The Kooks – Interview 2011 46 “We did a lot of stuff separately, which was different. I think that’s a natural progression for bands sometimes, when you have been together a long time. I did a lot of stuff ehm, you know in the studio on my own…”23 “It was really good, I mean it was very different again because we were building tracks up, we were trying…it was kinda like we didn’t really know what we were doing, because usually we just play guitars and we just get recording and we are in the room, and then the producer would do all the other stuff, but on this one we took more of a production role and we all got really involved in it.” 24 “America’s been really great for us, very un-judgmental […] there’s so much space there for you to put your music out and to have your own thing going on while you don’t have to be sort of homogenized…”25 “…we just did a German tour when we were playing, like music halls…” 26 “Sometimes the sound can be a bit difficult, but if you get it spot on, it can be really amazing…”27 0.28-0.40 0.56-1.16 25 1.24-1.40 26 2.00-2.03 27 2.15-2.20 23 24 47 48 When Rah Meets Chav: Mock Accents in Contemporary British Pop Music 48