TiffanyCrook_MEd_Masters_Thesis

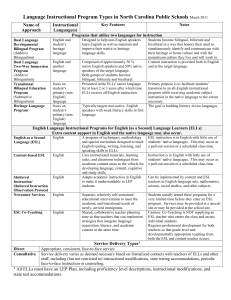

advertisement