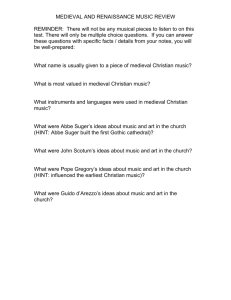

II. Church Architecture and Its Incorporation of Art

advertisement