Arbitrability in the United States–the Recent Decision of the

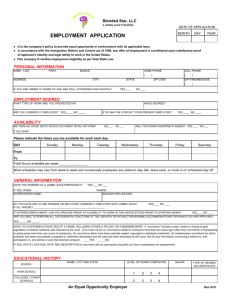

advertisement

Arbitrability in the United States – the Recent Decision of the Supreme Court in the CompuCredit corp. at. Al. v. Greenwood et.al Dora ZGRABLJIĆ ROTAR UDK 347.991(73) 347.918(73) kategorizacija rada Over the last thirty years, the United States Supreme Court has enacted an extreme pro-arbitration policy. After establishing that the Federal Arbitration Act reflects a liberal policy favouring arbitration, starting with the seminal decision in Mitsubishi Motors in which antitrust claims have been declared arbitrable in the United States, the Supreme Court has enforced arbitration agreements in matters that have traditionally been held non-arbitrable in almost every legal system. In recent years the Supreme Court has enforced arbitration clauses in consumer contracts of adhesion justifying it by the strong federal policy in favour of arbitration. The last one in the stream of decisions – CompuCredit v. Greenwood – was rendered in January 2012. The Supreme Court held that Credit Repair Organization Act claims are arbitrable, even though the Act imposes an obligation to inform the buyers that they have a non-waivable right to sue the credit repair organization. In this paper the decision in CompuCredit is analyzed with the emphasis on the inconsistencies in the Court’s argumentation. Key words: arbitrability, United States Supreme Court, Federal Arbitration Act, Credit Repair Organization Act, CompuCredit v. Greenwood I. Introduction United States Arbitration Act (known as the Federal Arbitration Act) was passed in 1925, with the idea to influence the general negative judicial attitude towards resolving disputes in arbitration.1 However, the scepticism towards arbitration remained unchanged for a number of years.2 Although a US delegation did participate in the negotiations for the New York Convention, the US was not among the original signatories of the Convention.3 The Convention was later codified and implemented through Chapter 2 of the FAA. However, decisions of the Supreme Court played the most important role in the strong pro-arbitration policy currently in the United States, especially when it comes to issues of arbitrability of claims. Dora Zgrabljić Rotar, LLM, Teaching Assistant, Faculty of Law, University of Zagreb Abby Cohen Smutny & Hansel T. Pham, Enforcing Foreign Arbitral Awards in the United States: The Non-Arbitrable Subject Matter Defense, 657 J. INT’L ARB. 25(6) 658 (2008). 2 Id. 3 Id. 1 In the New York Convention, arbitrability is defined as capability of settlement by arbitration.4 In some countries, notably in the United States, the term “arbitrability” is also used in a wider sense, namely as “covering the whole issue of the tribunal’s jurisdiction”.5 In this paper the term “arbitrability” is not used in this wider sense, but rather, how it is defined in the New York Convention. 6 Articles II and V(a)(2) of the New York Convention allow the national legislator to declare certain types of disputes non-arbitrable.7 The scope of arbitrable disputes differs from nation to nation, and most often include “disputes concerning labour or employment grievances, intellectual property, competition (antitrust) claims, real estate, consumer claims, and franchise relations.”8 The traditional view holds that limits on arbitrability arise from public policy.9 Tendencies have moved towards tying arbitrability of disputes to “efficiency and effectiveness of the arbitration process,”10 i.e. allowing arbitration of all disputes that can effectively be resolved in arbitration, notwithstanding the public policy concerns. However, “many arbitration laws still delineate inarbitrability on the basis of criteria related to public policy.”11 In particular, restrictions on consumer arbitration have been subject to extensive debate throughout the past years. There are several concerns which arise when considering allowing disputes between businesses and consumers to be resolved in arbitration proceedings. They include: 1. Unequal bargaining positions of the parties when concluding an arbitration agreement;12 2. Sophistication of consumers during the contract formation process;13 3. A concern that as a financial matter, the process by which the consumer disputes are arbitrated, cannot be fair to consumers; 4. Cost-effectiveness of resolving disputes involving small claims by arbitration;14 and 5. A concern that national policies designed to protect consumers will not be adequately enforced or will not be enforced at all.15 The European Union has traditionally relied on a policy that assumes that the consumer is a weaker contractual party. In the light of that policy, among other legislative efforts, the Directive on Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts provides that the court will decide whether a particular contract term is unfair and, thus, void. The Directive does not declare all predispute arbitration agreements in consumer contracts to be unfair terms. However, it seems that the European Court of Justice is going into precisely that direction. The United States Supreme Court has, on the other hand, readily upheld “international expansion of arbitrability to areas of economic activity heavily impregnated with public interest.”16 The policy on the arbitrability of pre-dispute arbitration agreements has favoured arbitration ever since the seminal decision in the Mitsubishi case, where the Supreme Court held that "Having made the bargain to arbitrate, the party should be held to it unless Congress itself has evinced an intention to preclude a waiver of judicial remedies for the statutory rights at issue."17 Although this liberal approach to arbitrability has been shaken with the Congress’ introduction of the Arbitration Fairness Act18 and the Fair Arbitration Act19 first in 2007, and then reintroduced in 2011,20 it seems that the United States is still successfully resisting this detrimental policies. 4 New York Convention, arts. II(1)., V(2)(a). Mistelis & Brekoulakis, supra note 4, at 5. 6 For various definitions of arbitrability see id. 7 New York Convention, arts. II(1)., V(2)(a). 8 GARY B. BORN, INTERNATIONAL ARBITRATION AND FORUM SELECTION AGREEMENTS: DRAFTING AND ENFORCING 130 (2010). 9 Mistelis & Brekoulakis, supra note 4, at 8. 10 Id. at 9. 11 Id. at 22. 12 Born, supra note 24 at 827. 13 Id. 14 Id. 15 Catharine Rogers, The Arrival of the "Have-Nots" in International Arbitration, 8 Nev. L.J. 341, 341 (2007). 16 Mistelis & Brekoulakis, supra note 4, at 57. 17 Mitsubishi Motors, 473 U.S. at 628. 18 Arbitration Fairness Act, S. 1782, 110th Cong. (2007). 19 Fair Arbitration Act, S. 1135, 110th Cong. (2007). 20 The two acts would amend the U.S. Federal Arbitration Act and declare “that no pre-dispute arbitration agreement shall be valid or enforceable if it requires arbitration of: (1) an employment, consumer, or franchise dispute, or (2) a dispute arising 5 However, in its recent decision in CompuCredit21 the United States Supreme Court has gone to the other extreme. Even though the issue was correctly qualified as one of arbitrability of CROA claims, the Court’s understanding of the Congress’ intention raises some problems. The Court’s interpretation of the words “right to sue” go against the purpose of the CROA, and indicates a lack of sensibility towards the understanding of the underlying purposes of declaring certain groups of claims nonarbitrable. For a better understanding of the Supreme Court’s 2012 decision in CompuCredit, it is important to have some information on the relevant case law history. Thus, an outline of the relevant cases is provided supra. II. Relevant case-law history a) Mitsubishi Motors Corporation v. Soler Chrysler-Plymouth, Inc. 22 Mitsubishi Motors is a seminal US case dealing with objective arbitrability. Favorable treatment of arbitration clauses when it comes to arbitrability of certain matters that are traditionally regarded as important issues of public policy, especially in international settings, has been evident in recent decisions of US courts.23 The beginning of this trend can be traced to a relatively recent decision of the United States Supreme Court in Scherk v. Alberto-Culvar Co.24 However, the Mitsubishi decision finally set the ground for answering “the question of whether and to what extent the “public law” matters such as securities law violations and antitrust claims may be subject to arbitration.”25 In Mitsubishi, an automobile manufacturer from Japan brought an action in Federal District Court to compel arbitration in accordance with the arbitration agreement it had with its distributor from Puerto Rico.26 The agreement between the parties contained an arbitration clause providing for arbitration by the Japan Commercial Arbitration Association. The Japanese manufacturer claimed “nonpayment of stored vehicles, contractual storage penalties, damage to manufacturer’s warranties and good will, expiration of distributorship, and other breaches of sales procedure agreement.”27 The distributer counterclaimed, inter alia, based on alleged violations of the Sherman Antitrust Act, which, he argued, cannot be resolved by arbitration.28 The District Court ordered arbitration, but the Court of Appeals reversed on the grounds that the “the rights conferred by the antitrust laws are inappropriate for enforcement by arbitration.”29 The Supreme Court reversed the Circuit Court, setting the grounds for a very broad understanding of the types of disputes that can be resolved by arbitration in the United States. The Supreme Court conducted a two-step analysis. In the first step it examined whether the scope of the arbitration agreement covered statutory claims. After finding that it did, the Court examined whether antitrust claims are arbitrable. under any statute intended to protect civil rights or to regulate contracts or transactions between parties of unequal bargaining power.” Mistelis & Brekoulakis, supra note 4, at 23. 21 CompuCredit Corp. v. Greenwood, 132 U.S. 665 (2012). 22 Mitsubishi Motors Corporation v. Soler Chrysler-Plymouth, Inc., 473 U.S. 614 (1985). 23 RONALD BRAND, FUNDAMENTALS OF INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS TRANSACTIONS 389 (2d ed. 2011). 24 In Scherk the court found that the claims under The Securities Exchange Act are arbitrable, despite the precedent in Wilko v. Swan in which it decided that claims under the Securities Act are not arbitrable. Id. 25 Id. 26 Mitsubishi Motors, 473 U.S. at 614. 27 Id. 28 Id. 29 Id. On the issue of scope, the distributer argued that statutory claims could not be resolved in arbitration if they have not been explicitly mentioned in the arbitration agreement.30 The Court dismissed the argument by saying that there is nothing in the Federal Arbitration Act that would provide a basis for this kind of conclusion.31 The Court reasoned that, in general, statutory claims can be arbitrable and the question whether particular claims under a particular Statute are non-arbitrable should be determined by the Congress in that particular Statute.32 The Court reasoned that it should be assumed that “if Congress intended the substantive protection afforded by a given statute to include protection against waiver of the right to a judicial forum, that intention will be deducible from text or legislative history.”33 It further explained that the intention of the Congress is crucial in determining arbitrability of particular statutory claims.34 The second issue was whether federal antitrust claims under the Sherman Act are non-arbitrable even though there was a valid arbitration agreement.35 The Court based its decision for upholding the arbitration agreement in this case on the fact that the contract in question was an international contract: “it will be necessary for national courts, to subordinate domestic actions of arbitrability to the international policy favouring commercial arbitration.”36 Nevertheless, lower courts, and the Supreme Court, have subsequently extended the arbitrability of antitrust claims to purely domestic contracts.37 In its decision, the Court interpreted the obligations under the New York Convention. Article II(1) sets the groundwork for contracting states to allow for certain groups of disputes to be non-arbitrable and the Court acknowledged that and concluded: “Doubtless, Congress may specify categories of claims it wishes to reserve for decision by our own courts without contravening this Nation’s obligations under the Convention.”38 The Court in Mitsubishi expressed its view that the exception to arbitrability found in New York Convention, article II(1) is to be used very narrowly, resulting in the final decision that antitrust claims in the United States are arbitrable.39 b) Shearson/American Express, Inc. v. Eugene McMahon40 Shearson/American Express involved a dispute between Shearson, a brokerage firm and two of its customers, Eugene and Julia McMahon. Their customer’s agreement included the following arbitration clause: Unless unenforceable due to federal or state law, any controversy arising out of or relating to my accounts, to transactions with you for me or to this agreement or the breach thereof, shall be settled by arbitration in accordance with the rules, then in effect, of the National Association of Securities Dealers, Inc. or the Boards of Directors of the New York Stock Exchange, Inc. and/or the American Stock Exchange, Inc. as I may elect. 41 The McMahons sued Shearson together with May Ann McNulty, the representative who handled their claims, for violations of the Securities Exchange Act (Exchange Act)42 and the Racketeer Influenced 30 Id. at 625. Id. at 627. 32 Id. at 627, 628. 33 Id. at 628. 34 Id. 35 Id. 36 Id. at 639. 37 GARRY B. BORN, INTERNATIONAL COMMERCIAL ARBITRATION 785 (2009). 38 Id. at 639. 39 Mitsubishi Motors, 473 U.S. at 614. 40 Shearson/American Express, Inc. v. Eugene McMahon, 482 U.S. 220 (1987). 41 Id. at 223. 42 Securities Exchange Act, 15 U.S.C. § 78a (1934) [hereinafter: Exchange Act]. 31 and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO).43 The question put forth was whether the claims under those two acts could be resolved in arbitration. The Southern District Court of New York held that the claims were arbitrable under the Exchange Act but not under the RICO, but the Court of Appeals reversed and decided that neither of the claims was arbitrable. The Supreme Court found that claims based on the Exchange Act and claims based on RICO are capable of being settled by arbitration, once again confirming its overall pro-arbitration policy.44 As in Mitsubishi, the Court found that the Federal Arbitration Act “establishes a federal policy favouring arbitration”45 subject to an exception of non-arbitrability when it can be proven that the Congress deemed a particular set of claims non-arbitrable. The Court further cited Mitsubishi when explaining that claims will be considered to be non arbitrable when the intent of the Congress is “deducible from [the statute’s] text or legislative history”, but added a very important reason “or from an inherent conflict between arbitration and the statute’s underlying purposes.”46 In Shearson, the Court further noted that “the burden is on the party opposing arbitration to show that the Congress intended to preclude a waiver of judicial remedies for the statutory rights at issue.”47 The Exchange Act contained a jurisdictional provision similar to that found in CompuCredit. In establishing that claims under the Exchange Act were arbitrable, the Court distinguished Wilko v. Swan, in which such provisions have been taken as evidence that there was a Congressional intent to bar arbitration. The decision held that “that case must be read as barring waiver of a judicial forum only were arbitration is inadequate to protect the substantive rights at issue.”48 In Shearson, the Court basically followed its decision in Mitsubishi, adding an important conclusion that when the Congress wants to bar certain claims from being resolved in arbitration, Congress’ intention must be “discernible from the text, history, or purposes of the statute.”49 In the case of both the Exchange Act and RICO the Court found that there is no “irreconcilable conflict between arbitration” and the statutes’ underlying purposes.50 c) Robert D. Gilmar v. Interstate/Johnson Lane Corporation51 In Gilmar, a registered securities representative working for Interstate had his employment terminated at the age of 62. The plaintiff sued for age discrimination in accordance with the provisions of the Age Discrimination in Employment Act (ADEA). The defendant filed a motion to compel arbitration based on the registration application of the plaintiff, which contained an arbitration agreement.52 The United States District Court for the Western District of North Carolina denied the motion. The Court of Appeals reversed. The United Sates Supreme Court decided that ADEA claims could be subject to arbitration. The Court again, as in Shearson, based its decision on the fact that there was no conflict between arbitration and a federal act’s underlying purpose,53 noting that “there is no inconsistency between the important social policies furthered by the ADEA and enforcing agreements to arbitrate age discrimination claims.”54 Once again the Court confirmed that the purpose of the 43 Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, 18 U.S.C. §§ 1961–1968 (1970) [hereinafter: RICO]. Shearson, 482 U.S. at 220. 45 Id. 46 Id. at 227. 47 Id. at 220. 48 Id. at 221. 49 Id. at 227. 50 Id. 51 Robert D. Gilmar v. Interstate/Johnson Lane Corp., 500 U.S. 20 (1991). 52 Id. 53 Id. at 23. 54 Id. 44 federal act in question is of the outmost importance when it comes to determining whether the claims under that act are arbitrable. III. CompuCredit corp. at. Al. v. Greenwood et.al - facts of the case In 2008 a group of individuals who received an Aspire Visa credit card advertised by the CompuCredit Corporation and issued by the Columbus Bank and Trust filed a class-action complaint against both CompuCredit and Columbus in the United States District Court for the Northern District of California, alleging violations of the Credit Repair Organization Act (CROA). 55 The plaintiffs alleged that the defendants misrepresented that the credit card could be used to rebuild poor credit. The fees applicable upon the opening of the credit card were almost as high as the advertised credit limit, resulting in a usable limit of the credit card that was much lower than the limit advertised.56 The advertised credit limit was $300 while the fees for opening the credit card came to $257. The advertisement had a notice about the fees buried in small print under other boilerplate language.57 The application for the credit card signed by the plaintiffs included the following provision in small print: “Any claim, dispute or controversy (whether in contract, tort, or otherwise) at any time arising from or relating to your Account, any transferred balances or this Agreement (collectively, ‘Claims’) upon the election of you or us, will be resolved by binding arbitration…”58 Based upon the arbitration clause, the defendants, CompuCredit and the Columbus bank, filed a motion to compel arbitration. Plaintiffs argued that the arbitration clause was unenforceable since claims under CROA were non-arbitrable.59 The District Court for the Northern District of California ruled in favour of the plaintiffs and found that the claims under CROA were non-arbitrable.60 The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed.61 The Supreme Court reversed the decision (with a majority of six justices, a concurring opinion by two justices, and a dissent by one justice) and upheld the enforceability of the arbitration agreement.62 IV. Issue – Arbitrability of CROA claims The question the Supreme Court articulated was whether claims arising under CROA are arbitrable. The starting point of this analysis was the Federal Arbitration Act: A written provision in any maritime transaction or contract evidencing a transaction involving commerce to settle by arbitration a controversy thereafter arising out of such contract or transaction… shall be valid, 55 Credit Repair Organizations Act, 15 U.S.C. § 402 (West 2000 & Supp. 2005) [hereinafter: CROA]. CompuCredit, 132 U.S. at 665. 57 Greenwood v. CompuCredit Corp., 617 F. Supp. 2d 980, 982 (Dist. Ct. of North. Cal. 2009). 58 CompuCredit, 132 U.S. at 668. 59 Id. at 667. 60 “The Court concludes that Congress intended claims under the CROA to be non-arbitrable. Requiring a dispute to be resolved through arbitration is incompatible with CROA's non-waivable right to sue. Therefore, the Court finds that the arbitration clause is void.” Greenwood, 617 F. Supp. 2d. at 988. 61 Id. 62 CompuCredit, 132 U.S. at 665. 56 irrevocable, and enforceable, save upon such grounds as exist at law or in equity for the revocation of any contract.63 There is no dispute that the provision, as the Court found, favours arbitration64 and that the underlying purpose of the provision was to decrease “judicial hostility to arbitration.”65 However, it has been long established that not all disputes are capable of being settled by arbitration. The New York Convention ensured the right for its contracting parties to keep certain claims in the exclusive jurisdiction of the courts, through objective and subjective arbitrability. 66 The arbitrability at issue in CompuCredit is objective arbitrability, i.e. question whether “the subject-matter of the dispute submitted to arbitration can be resolved by arbitration.”67 The Federal Arbitration Act implements the New York Convention, however it does not provide rules on what subjects are to be considered arbitrable. Whether a set of particular matters can be the subject of arbitration has always been established through judicial interpretation of other statutes, “most of which do not expressly address the issue of arbitrability.”68 In § 402 of CROA, Congress provided that the purpose of CROA is, amongst others: (1) to ensure that prospective buyers of the services of credit repair organizations are provided with the information necessary to make an informed decision regarding the purchase of such services; and (2) to protect the public from unfair or deceptive advertising and business practices by credit repair organizations.69 In § 405 it further explains that all credit repair organizations have to inform consumers of the rights the consumers have. Among others, credit repair organizations must comply with the following required disclosure: “You have a right to sue a credit repair organization that violates the Credit Repair Organization Act. This law prohibits deceptive practices by credit repair organizations.”70 § 408 of CROA further provides that “[a]ny waiver by any consumer of any protection provided by or any right of the consumer under this title (1) shall be treated as void; and (2) may not be enforced by any Federal or State court or any other person.”71 In several other sections, statutory language also includes references to “action”, “class action” and “court.” 72 For example, in § 409 of CROA entitled “Civil Liability,” the ways to compute damages have been explained in the following way: (A) Individual actions.--In the case of any action by an individual, such additional amount as the court may allow; (B) Class actions.--In the case of a class action, the sum of (i) the aggregate of the amount which the court may allow for each named plaintiff; and (ii) the aggregate of the amount which the court may allow for each other class member, without regard to any minimum individual recovery. 73 Based on all these provisions, the plaintiffs in CompuCredit claimed that under CROA they had a right to sue in court that could not be waived.74 63 Federal Arbitration Act, 9 U.S.C. § 2 (1925). “The provision establishes “a liberal federal policy favoring arbitration agreements”. Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospi- tal v. Mercury Constr. Corp., 460 U. S. 1, 24 (1983). See also, e.g., Concepcion, supra, at __ (slip op., at 4); Gilmer v. Interstate/Johnson Lane Corp., 500 U. S. 20, 25 (1991). It requires courts to enforce agreements to arbitrate accord- ing to their terms. See Dean Witter Reynolds Inc. v. Byrd, 470 U. S. 213, 221 (1985).” CompuCredit, 132 U.S. at 667. 65 CompuCredit, 132 U.S. at 668. 66 Discussed supra under I. 67 Gaillard & Savage, supra note 10 at 313. 68 Born, supra note 38 at 781. 69 CROA § 402. 70 Id. § 405. 71 Id. § 408. 72 Id. § 409. 73 Id. 74 CompuCredit, 132 U.S. at 667. 64 V. The Supreme Court’s opinion in CompuCredit case – analysis of the decision The decision in CompuCredit included a majority opinion joined by six justices. Justice Scalia delivered the opinion in which Justices Roberts, Kennedy, Thomas, Breyer, and Alito joined. Justices Sotomayor and Kagan concurred, while Justice Ginsburg filed a dissenting opinion. The decision of the majority includes five reasons supporting giving effect to arbitration agreements in the case. The concurring opinion adds another one. All six of them are discussed supra in detail. The Court has already established a line of reasoning in Mitsubishi, McMahon, and Gilmar. There is no doubt that the FAA provides for a federal policy favoring arbitration. There is also no doubt that claims under federal statutory acts can be subject to arbitration. However, there is also no doubt that if the Congressional intent to bar arbitration for claims under certain acts is proven, claims under those acts will be considered to be non-arbitrable and thus only capable of being settled in the courts. The intent of the Congress as to the non-arbitrability of the statutory claims has to be established by examining the text, history and purpose of the statute75. In the case of CROA the text does not explicitly provide that the claims cannot be resolved in arbitration. Therefore, the issue that needed to be decided in CompuCredit was whether CROA reflects an implied intention of Congress to find claims under CROA non-arbitrable. 1. The disclosure provision only provides consumers the right to receive the statement and not the right to sue in court Justice Scalia reasoned that the Ninth Circuit Court’s decision was flawed because it was based on the mistaken premise that the provision in CROA requiring credit repair organizations to give notice to consumers that they have the right to sue actually provides consumer the right to sue in the court. “The only consumer right it creates is the right to receive the statement, which is meant to describe the consumer protection that the law elsewhere provides.”76 The decision further explains that the disclosure provides information that the consumers “might otherwise not possess.”77 There are two problems with the Court’s interpretation. First, the consumer already has a right to sue, even absent the notice. Thus, it would make no sense to give the consumers a notice about something they already have a right to do under the law. It is reasonable to assume that every consumer knows he has a right to sue in court. It would, on the other hand, be unreasonable to assume that the notice contains a notorious fact, already known to every addressee of the notice. The plausible conclusion is that the intent of the notice is to inform the consumers that they have an exclusive right to go to court. However, even if the notice is here only to provide the consumers with an explanation of their rights, it must be assumed that the given explanation is accurate and is not misleading. The accuracy of the information provided in the notice should be assessed from the perspective of the addressee of the notice, i.e. the buyer of the credit. Otherwise, the disclosure provision would be contrary to the statutory purpose of CROA: to provide all information necessary for the buyers of the credit to make an informed decision. 75 Mitsubishi Motors, 473 U.S. at 628. CompuCredit, 132 U.S. at 670. 77 Id. 76 This leads to the second problem in the Court’s reasoning. If Congress had intended for CROA claims to be arbitrable, the requirement to give notice stating that “you have a right to sue” would mean that Congress instructed the Credit Repair Organizations to give misleading information to the buyers of the credit, since it would be reasonable to assume the majority of laypersons would interpret the disclosure provision as giving them the right to sue in a court. Therefore, it seems that this distinction between the notice of rights and the actual rights is not relevant here. Because, the notice only makes sense and is in line with the intent of Congress to provide accurate information to the consumers, if the notice reflects the actual rights of the buyers of the credit. Therefore, the real issue is: what is the interpretation of the words “you have the right to sue”? 2. The CROA references to “action”, “class action” and “court” do not show that consumers have a right to go to court Justice Scalia also found that the repeated use of the words “action”, “class action,” and “court” does not lead to the conclusion that it was Congress’ intent to provide courts with non-waivable exclusive jurisdiction for CROA claims, because “these references cannot do the heavy lifting that respondents assign them.”78 Basing his analysis on Mitsubishi, McMahon and Gilmar, Scalia noted that the Supreme Court has “repeatedly recognized that contractually required arbitration of claims satisfies the statutory prescription of civil liability in the court.”79 However, the Court follows this by admitting that none of the statutes in those cases contained a nonwaiver provision, as the one found in CROA § 408. In doing this, the majority opinion effectively distinguishes the facts of CompucCredit from the history of case law on which the Court bases its decision. Recognizing this result, he then follows with an attempt to dismiss the waiver provision. 3. Dismissing the waiver Basing his reasoning on the interpretation of the meaning of the words “right to sue”, Justice Scalia finds that the meaning of those words is not “the right to sue in all competent courts disabling the parties from adopting a reasonable forum selection clause,”80 but rather the right to sue in any competent court. He concludes that the waiver is intended only to preserve “the guarantee of the legal power to impose liability.”81 Justice Scalia’s analysis on the waiver issue could be plausible only if the Court’s definition of the words “right to sue” is accepted, thus creating a circular analysis. If the words “the right to sue” are interpreted as meaning that there is a right to both litigation and arbitration, depending on other circumstances, then the non-waiver provision, as Justice Scalia points out, only means that a consumer cannot waive their legally guaranteed protection to have some form of dispute resolution. However, if those words are interpreted to provide the consumers an exclusive right to sue in court then the nonwaiver provision means that they cannot waive their right to go to court by agreeing to go to arbitration. This reasoning confirms the conclusion that “the question on which this case turns is what Congress meant when it created a nonwaivable ‘right to sue’.”82 78 Id. Id. at 671. 80 Id. 81 Id. 82 Id. at 678. 79 4. The words “right to sue” include the right to sue in a court of law and the right to sue in arbitration The buyers of the credit in CompuCredit claimed that an interpretation similar to the one Justice Scalia and the majority adopt would be misleading for the vast majority of consumers if it truly included both the right to sue in a court of law and the possibility of resolving a dispute in arbitration. The Court found the opposite to be true and explained that “the disclosure provision is meant to describe the law to consumers in a manner that is concise and comprehensible to the layman – which necessarily means that it will be imprecise.”83 However, by adopting this explanation the Court tramples the very purpose of CROA, which is clearly stated as “(1) to ensure that prospective buyers of the services of credit repair organizations are provided with the information necessary to make an informed decision regarding the purchase of such services; and (2) to protect the public from unfair or deceptive advertising and business practices by credit repair organizations.”84 If the main purpose of the CROA is to provide accurate information to consumers, in order to enable them to make an informed decision, then the reasoning of the Court that the information provided to the consumers will necessarily be imprecise collides with the intention of Congress. This reasoning, as well as the decision based on it, is also in direct conflict with the prior decisions of the Supreme Court on the issue. In determining the arbitrability of certain statutory claims, the court has repeatedly held, that the purpose of the statute will be of the outmost importance. Justice Scalia’s opinion admits that, under his interpretation of CROA, the notice of the right to sue is misleading to consumers. However, he continues with an even more questionable explanation on how consumers should understand the notice of the right to sue: This is a colloquial method of communicating to consumers that they have the legal right, enforceable in court, to recover damages from credit repair organizations that violate CROA. We think most consumers would understand it in this way, without regard to whether the suit in court has to be preceded by arbitration proceedings.85 In contrast, Justice Ginsburg states in her dissent that the “audience in the CROA is not composed of lawyers and judges accustomed to nuanced reading of statutory texts, but laypersons who receive a disclosure statement in the mail.”86 It would be hard to believe that a layperson would understand his or her right to sue under the CROA as meaning – the right to have either court or arbitration proceedings. 5. Congress’ intention if it wanted to declare CROA disputes non-arbitrable should have been clearly stated Justice Scalia’s last argument is that “had the Congress meant to prohibit these very common provisions in the CROA, it would have done so in a manner less obtuse than what respondents suggest.”87 However, as pointed out in both the dissent and the concurring opinion: I do not understand the majority opinion to hold that Congress must speak so explicitly in order to convey its intent to preclude arbitration of statutory claims. We have never said as much, and on numerous occasions have held t hat proof of Congress’ intent may also be discovered in the history or purpose of the statute in question.88 83 Id. at 671. CROA § 402. 85 CompuCredit, 132 U.S. at 672. 86 Id. at 678. 87 Id. at 672. 88 Id. at 675. 84 The analysis of Congressional intent as an interpretive method has been established by the Supreme Court in numerous previous cases. Moreover, the rule that an implied intention of Congress to deem a certain group of claims to be non-arbitrable can be drawn from the most important case on the issue – Mitsubishi; “We must assume that if Congress intended the substantive protection afforded by a given statute to include protection against waiver of the right to a judicial forum, that intention will be deducible from text or legislative history.”89 6. The concurring opinion’s argument on the burden of proof Justices Sotomayor and Kagan agreed with Scalia in the ultimate holding, but disagreed with his interpretation of how a normal person would understand the required CROA disclosure. They stated that Those for whom Congress wrote the Act – lay readers “of limited economic means and … inexperienced in credit matters,” § 1679(a)(2) – reasonably may interpret the phrase “right to sue” as promising a right to sue in court. And it is plausible to think that Congress, aware of the impact of its words, intended such a construction of the liability provision.90 However, they agreed with the final decision of the majority. They pointed out the rule that “respondents, as the opponents of arbitration, bear the burden of showing that Congress disallowed arbitration of their claims.”91 They concluded that “the parties’ arguments are in equipoise”92 and that since the respondents (the consumers) here bear the burden of proving the intent of the Congress, arbitration should be allowed. VI. Conclusion The issue in CompuCredit was whether Congress intended to make the claims under CROA nonarbitrable. If the non-waivable provision on “the right to sue” under CROA is defined as banning arbitration and providing consumers the exclusive right to have their disputes resolved in a court, it means that all CROA claims are non-arbitrable, irrespective of whether an arbitration agreement has been concluded pre or post arbitration. However, in reality it is unlikely that the arbitration agreement between credit organizations and consumers will ever be concluded in a negotiated post dispute setting. This particular type of contract is especially tainted by the unequal bargaining powers of the contracting parties, since consumers are likely to sign up for arbitration only because it will be a precondition to getting the loan. Congressional intent to ban arbitration in claims that arise under the contracts where one side is in an evidently take-it-or-leave-it position can also be evidenced by analogy with other federal laws which prohibit arbitration in consumer matters. For example, creditors extending consumer credit to members of the armed forces and their covered dependents cannot require the borrower to submit to 89 Mitsubishi Motors, 473 U.S. at 628. CompuCredit, 132 U.S. at 675. 91 Id. 92 Id. 90 arbitration to resolve disputes93, and pre-dispute agreements requiring arbitration are prohibited for loans secured by residences.94 The question of whether these sorts of disputes are reasonably established as non-arbitrable should be clearly distinguished from the question of whether the Congress has impliedly proclaimed them to be non-arbitrable. In its previous decisions, the Court had already established that Congress has a right to proclaim certain groups of claims as non-arbitrable, and the courts have already on numerous occasions shown that the congressional intent can be express or implied. In this case it would be quite reasonable to argue that Congress did intend to proclaim all disputes under CROA to be non-arbitrable. If all the provisions of CROA are taken into account together with the stated purpose of the act, namely to “ensure that prospective buyers of the services of credit repair organizations are provided with the information necessary to make an informed decision,”95 and “to protect the public from unfair or deceptive advertising and business practices by credit repair organizations,”96 it seems that the decision of the Court is contrary to its formerly established practice. In both McMahon and Gilmar the Court decided that certain federal statutory claims are arbitrable.97 But in both cases the Court based its decision on the fact that there was no irreconcilable difference between the underlying purposes of the federal acts in question and allowing arbitration of claims that arose from those acts. In Gilmar, the Court based its opinion on the arbitrability of ADEA claims on the fact that “there is no inconsistency between the important social policies furthered by the ADEA and enforcing agreements to arbitrate age discrimination claims.”98 In CompuCredit there is both an underlying purpose of the Act and specific social policy behind CROA that point to the conclusion that there indeed was an implied intention of the Congress to declare the claims non-arbitrable. 93 10 U.S.C. § 987(e)(3) 15 U.S.C. § 1639c(e)(1) 95 CROA § 402. 96 Id. 97 Shearson/American Express, Inc. v. Eugene McMahon, 482 U.S. 220 (1987).Robert D. Gilmar v. Interstate/Johnson Lane Corp., 500 U.S. 20 (1991). 98 Gilmar, 500 U.S. at 23. 94