Media and Civil Society Participation: Removing a

advertisement

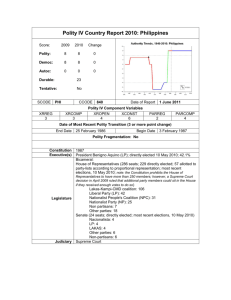

Removing a Corrupt President: The Role of Media, Civil Society Presentation by Malou Mangahas Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism December 2003 The Philippines: Fast Facts, Figures Filipinos like to call their country the Pearl of the Orient Seas. In truth, it is like a wasteland of dirt and pain, two elements that nurture pearl. Like a string of pearls, the Philippines is an archipelago with 7,107 islands, stretched across 300,000 square kilometers of land area. There are 16 administrative regions, 77 provinces, 500 cities and municipalities, and 30,000 plus barangays or villages. As of the May 2000 census, there are 76.5 million Filipinos, a population estimated to reach 80 million in 2001, at an average annual growth rate of 2.1 per cent. Up to 60 per cent of all Filipinos are below 21 years old. About 7 million work overseas as contract workers or migrants, many undocumented. There are 11,500 households and average family size is 3.4 persons. The government estimates poverty incidence at 28.4 percent, although the Asian Development Bank places it at 40 per cent. Simple literacy is very high at 93.9 per cent (1994 data) but functional literacy is only 81 per cent. By 2000, the average annual family income is estimated at P144,039, while average annual family expenditure, P118,002. The unemployment rate is placed at 10.2 percent of the workforce, and the underemployment rate, 15.3 per cent, as of October 2002. People Power, Episode 2 Four days of massive protest rallies capped by the withdrawal of support by generals of the Armed Forces forced the Philippines’ 13th President, Joseph Estrada, to step down on January 21, 2003. Multiple, parallel efforts by media and civil society exposed corruption in the government and Estrada’s unexplained wealth. Lawyers helped lawmakers prepare the impeachment complaint filed against Estrada with the House of Representatives, and joined the prosecution team in the Senate impeachment tribunal. Church leaders and businessmen lent moral and material support for the protest rallies, and openly took the side of the opposition as individuals or through various associations in the days leading to Estrada's decision to leave his post. Employers allowed their workers to join the protest rallies. Chief Justice Hilario Davide Jr. swore into office then Vice President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, vesting the new government with judicial and constitutional imprimatur and writing finis to the Estrada presidency. Of Mansions and Mistresses The Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ) published six stories and produced as many television documentaries from May to December 2001 on Estrada's multple mansions and mistresses. The first stories met with lukewarm response from leading newspapers and TV networks until Estrada buddy Luis "Chavit" Singson exposed the million-peso kickbacks that Estrada collected from illegal gambling and tobacco excise taxes. The first leads for the stories came from coffee shop talk, white papers and anonymous tipsters in Manila's vibrant rumor mill Earlier in January 2001, PCIJ organized a team of six reporters and researchers, all women, to work on the Estrada stories. The Research plan was pegged on: What could be documented? What could be verified? What will stick? Next, the PCIJ Team agreed to focus the research on the following concrete evidence of unexplained wealth: real estate, houses, corporate assets. Because Estrada kept a large and intricate network of spouses and friends, the Team also decided to assign the writers to specific spouses and cronies as their respective subjects of study. The Power of Paper The Paper Trail on Estrada's estate served as the backbone of the research effort. Student interns assisted researchers in lining up intermittently at Securities an Exchange Commission to gather GIS, articles of incorporation, financial statements, building and other permits, land registration records, statements of assets and liabilities on the Estrada properties. The research effort stretched on for six months and cost the PCIJ about P40,000 (about US$800) in photocopying fees. The research team compiled two boxes of documents on 66 companies that Estrada and his spouses, children and associates owned and controlled. Reverse search allowed by the SEC then provided a breakthrough in the research effort.. The enabling environment for the research effort was fairly well established in the Philippines. Regulatory agencies like the SEC has largely complied with the transparency clauses of anti-graft laws. The real burden on the research team was not so much the absence of documents but the tediousness and meticulous care required in ferreting out the truth. The research effort became so involved and tedious because of the vastness and layers of corporate veil that shrouded the Estrada properties. Resign, Impeach, Oust! EDSA People Power 2 had its roots in the latter part of 1999, when civil society groups started to write off the Estrada presidency as a gross disappointment. The Philippines' 13th president and the first with non-elite credentials -- a college dropout, he was given to gambling, drink and women, and spoke tortured English -- Estrada had trumpeted himself as "a man for the poor." Senior civil society leaders, however, advised the initially small circle of five NGOs to first gather solid evidence so the charges would stick. Failing this, the groups agreed that "even if we don't succeed, we could at least expose the issues and let people know." In time, bigger groups like the influential Makati Business Club joined in. Thus, when civil society leaders decided in November 2000 to gather all anti-Estrada groups within one umbrella coalition, KOMPIL 2, three modes of getting Estrada out of the presidency were adopted, representing the divergent points of view of the coalition members. Consensus was achieved on what was called a RIO (Resign, Impeach, Oust) strategy. Consensus was achieved as well on the sequence of protest calls KOMPIL will carry -- first "Estrada Resign," then "Impeach Estrada," and finally, "Oust Estrada." The groups failed, however, to achieve unity on the more contentious matter of "program of government," or what should happen after Estrada is ousted. On parallel track, Vice President Gloria Arroyo formed her "Constitutional Transition Committee" and assigned its members to keep in constant communication with KOMPIL 2 leaders. Churches & Traders The role of the churches -- Roman Catholic, Protestant, and Islamic -- that supported the anti-Estrada campaign cannot be over-emphasized. Church leaders from all denominations harnessed their moral influence on members, ministers, nuns and priests, administrators of church-run schools with command over students and teachers, to pack in the crowd at the EDSA shrine for four days straight. In like manner, Estrada counted on his loyal allies in the Iglesia ni Cristo -- a minority church of about 4 million adult members and virtually the only real voting bloc in the Philippines -- to pack in the crowd at the pro-Estrada rallies around the presidential palace, and later, against Mrs Arroyo. Business leaders are yet another equally important silent partner in EDSA People Power 2, as they were in EDSA People Power 1. Protest movements entail huge budgets and overheads, a burden that unavoidably falls always on businessmen. EDSA People Power 2 cost tens of millions of pesos to mount. The overhead expenses and campaign collateral (i.e. streamers, T-shirts, food, printing of pamphlets, transportation, sound system rental), entailed big costs. Residents of affluent villages enlisted women and children in food brigades to cook and serve meals for tens of thousands, an expense that cannot be billed in pesos and cents. An Interplay of Actors, Issues * A vibrant interplay of the right actors acting on the right issues at the right time made EDSA People Power 2 possible. In large measure, too, the Filipinos' unique, historical experiences with their political leaders, and the policy and social environment also enabled the effort. * Mounting a people power revolt is a fast, furious process that involves leaders and masses forging swift consensus on minimum common ground, and under pressure of limited time and resources. * The coalition members moved fast on the issues that united them, and thought it wise to skip the issues that divided them. Confronted by the question of who to install after Estrada, the constitutional successor, Vice President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, became the inevitable but not compelling answer. * By December 2000, Arroyo had organized a Constitutional Transition Committee of her closest advisers. The Committee consulted with the NGOs on "political and social programs" but made no commitments on what program of government Mrs Arroyo will implement once she takes power. People Power Scenarios As the impeachment trial of Estrada commenced in November 2000, KOMPIL embarked on "scenario-building efforts." They set a 30-day deadline for the trial to unfold, before launching their civil disobedience plans. KOMPIL anticipated any one of three likely scenarios could result from the trial: – Estrada would be exonerated; – Estrada would be convicted "by a mere stroke of a miracle;" or – The trial could stretch well beyond the congressional elections scheduled in May 2001. For all three scenarios, KOMPIL achieved general consensus to launch civil disobedience actions, as would be appropriate to individual groups. For instance, workers strikes or any combination of acts of civil disobedience were discussed. In the meantime, some NGO leaders started back-channel talks with certain military officers. KOMPIL’s contacts in the military imposed a condition for them to jump ship to the anti-Estrada side -- a big crowd or a big event to demonstrate that the people had lost faith in Estrada, a signal motive fore the Armed Forces to withdraw support. Civil Society’s Dilemma: Get In or Stay Out of Government? In the aftermath of People Power 2, one question caught civil society groups off-guard: Should their leaders serve in the Arroyo government, following their effort to help oust Estrada? KOMPIL 2 leaders decided to join government service, resulting in transition problems for their NGOs. The second-liners in a number of NGOs have not been fully prepared to take on leadership roles abandoned by the Arroyo appointees. The question continues to hound civil society groups: can NGO leaders serve best inside or outside government service? The day after victory, civil society leaders faced two equally urgent tasks. First, to consolidate the coalition. Second, to help run the government. In the meantime, KOMPIL leaders also had to rush back to the life and work they had, before the revolt beckoned. Thirty months hence, from 50 to 70 leaders and members of civil society groups in KOMPIL 2 are now in government service. Variably, they work in operations, policy planning and review, executive staff units in various departments, or sit on the boards of government financial institutions and corporations. Windfall: A few good results Civil society’s presence in government has yielded some positive, if tactical, results.: • Mrs Arroyo consults senior civil society leaders in the Cabinet on such policy issues as the peace talks with separatist Muslim rebels but it is not clear how much and how often they have prevailed in the testy debates that often hobble policy-making in the Philippines. • In a government bank where civil society leaders sit as board members, “a culture of dialogue” has been fostered between management and labor, resolving extended rows over pay and welfare issues. • Civil society leaders appointed to the social services sector have achieved a lot in the area of delivering basic services to slumdwellers and indigent communities, drawing in to the Arroyo side part of the large poor constituency of ousted President Estrada. Fallout: Weaker NGOs, Divided Civil Society Civil society’s decision to join government service has dissipated the shallow bench of NGO leaders, exacting a serious toll on the quality of leadership and cogency of issues of civil society. The Filipino public, by tradition very exacting in their expectations of civil society, remains ambivalent toward the new hybrid force of former civil society leaders who are now civil servants -- not quite activists anymore but not quite politicians and government bureaucrats as yet. Civil society has been split by the question on whether to support or criticize Mrs. Arroyo, and on what issues. Her decision to turn back on a promise not to run for president in May 2004 has dissolved a new coalition of NGOs. Only 2 of 32 NGO leaders who met in August 2003 decided to join her election campaign. Politics Hobbles the Court EDSA People Power 2 has dragged down the Supreme Court -- the singular institution that has consistently enjoyed positive public approval rating and the ultimate arbiter of conflict in the Philippines - and made it vulnerable to political criticism. Ousted President Estrada had filed a petition questioning the constitutionality of the decision of Supreme Court Justice Hilario Davide to swear in Mrs Arroyo as president. In a vote of 13-0 the high court threw out the petition, as well as a motion for reconsideration filed by Estrada’s lawyers. In 2003, members of the House of Representatives filed an impeachment complaint against the Supreme Court justices, for their role in installing Mrs Arroyo. This did not prosper. A second impeachment complaint against Chief Justice Hilario Davide Jr. passed with the vote of 88 lawmakers in October 2003. It alleged misuse of the Judicial Development Fund on repair and construction of the justices summer villas in northern Baguio City. The Perils of People Power People Power revolts have challenged the viability of the constitutional and legal processes for changing leaders. In its decision on the Estrada petition questioning the validity of the Arroyo government, the Supreme Court had to make fine, feeble, distinctions between EDSA 1 and 2. The high court ruled: “EDSA 1 involves the exercise of the people power of revolution which overthrew the whole government. EDSA 2 is an exercise of people power of freedom of speech and freedom of assembly to petition the government for redress of grievances which only affected the Office of the President. EDSA 1 is extra-constitutional… EDSA 2 is intraconstitutional. EDSA 1 presented a political question; EDSA 2 involves legal questions.” A justice, in a separate opinion, raised concern about “the use of people power to create a vacancy in the presidency,” citing that, “there is nothing in the Constitution to legitimize the ouster of an incumbent President through means that are unconstitutional or extraconstitutional.” ‘Short-cuts’ Weaken Institutions? EDSA 1 and 2 may have illustrated the Filipinos’ penchant for “shortcuts” and for “short-circuiting due processes.” The two people power episodes in the Philippines– the first against a repressive president, the second against a corrupt president – were in fact the triumph of “street politics” over due process, according to a political analyst. Filipinos resort to short-cuts precisely because most of them are poor, “ disempowered or unpempowered.” After people power revolts, the question that must dominate the public agenda is how to strengthen democratic institutions. Intermittent political squabbles that follow people power episodes render institutions as mere nominal structures constantly beholden to party politics.