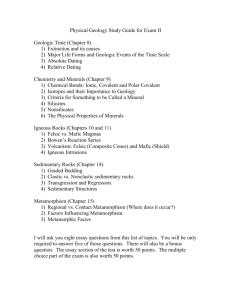

Igneous Rock Classification.

advertisement

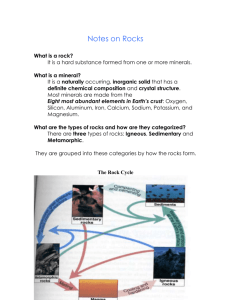

IGNEOUS ROCK CLASSIFICATION Prepared by Dr. F. Clark, Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, University of Alberta Oct. 05 FORMAL CLASSIFICATION SCHEMES Proper classification of igneous rocks requires that you identify the minerals present, as well as their proportions by volume percent of the whole rock, and recognize on the basis of textures whether the rock is intrusive or extrusive. There are various diagrams and tables that will allow you to do this with great precision, but for this presentation, we will use a much simplified version wherein we apply commonly used intrusive and extrusive rock names for igneous rocks of three, or perhaps four, broad compositional types. IGNEOUS ROCK COMPOSITION The chemical composition, which determines what minerals will crystallize, can be expressed as the sum of a number of oxides of common cations. For igneous rocks, the most important oxide is SiO2, or silica, most usually not in the form of the mineral quartz. The silica content ranges between approximately 40% and 70%. We notice that the total content of magnesium and iron is generally in inverse proportion to the silica content. Thus rocks deficient in silica are rich in Mg+Fe, and are called mafic, or even ultramafic, whereas rocks high in silica are generally depleted in Mg+Fe, and are called felsic. Rocks between these extremes are intermediate. COMPOSIITON AND COLOUR We observe that the colour of most igneous rocks is controlled by the composition, which in turn of course controls the mineralogy. Thus, mafic rocks, rich in Mg+Fe, have a higher proportion of mafic minerals, which are typically dark, whereas felsic rocks are low in Mg+Fe, and are therefore typically much lighter in colour, being dominated by quartz and feldspars. This gives rise to the concept of Colour Index, which is the volume percent of the rock that is accounted for by mafic minerals (e.g. olivine, pyroxene, amphibole, and biotite). As we shall demonstrate, there is not necessarily a direct correspondence between Colour Index and the colour we observe for a given rock. INTRUSIVE IGNEOUS ROCKS The coarse grain size produced by slow cooling of magmas makes the task of mineral identification so much easier for intrusive rocks. We will present images of ultramafic, mafic, intermediate, and felsic igneous intrusive rocks, in turn. As one might expect, the general trend will be for the rocks to be progressively lighter as we move from mafic to felsic. DUNITE This is an ultramafic (very low silica, very high Mg+Fe) igneous intrusive rock. The bulk of these specimens consists of glassy green olivine crystals on the order of 1mm or slightly finer. The few black grains [black arrows] are of a pyroxene group mineral. Not even plagioclase feldspar is found in these ultramafic rocks. GABBRO This is a mafic igneous intrusive rock. Mafic igneous rocks typically have mixtures of pyroxene [black arrows, as well as the yellow arrows highlighting a megacryst] and calcium-rich plagioclase feldspar, which shows up in this specimen as dark green crystals [blue arrows] that are nevertheless lighter than pyroxene. DIORITE This speckled coarse-grained specimen is an intermediate composition igneous intrusive rock. With intermediate composition, the Mg+Fe content of the magma is now tied up in the crystallization of the black minerals biotite [more so in this specimen] and amphibole. The white mineral is plagioclase feldspar, and there is minor clear, glassy quartz [purple arrows]. GRANITE – This is a felsic intrusive rock. The coarse grain size and variety of minerals makes granite an attractive choice for building stone, and less happily, grave markers as well. The most abundant mineral is yellowish potassium feldspar [turquoise arrows], followed by grey glassy quartz [mauve arrows], then black, relatively dull amphibole [no arrows], and finally shiny black biotite [green arrows]. GRANITE – yet again. In comparison with the previous specimens, this example of granite has pink potassium feldspar [turquoise arrows; note the well-developed cleavage faces], much less quartz [mauve arrows], much more amphibole, and more biotite [green arrows] as well. It might not technically be a granite [too little quartz, using rigorous classification schemes], but the name will do for our purposes. GRANITE This is a sample of the Kuskanax Intrusion, in the Canadian Cordillera, recovered from Nakusp, BC. Such boulders are abundant. This granite is much more fine-grained than the previous examples, and at first glance is dominated by yellowish potassium feldspar. However, there is substantial quartz content [mauve arrows], whose presence is masked by the feldspar. The black grains are amphibole. GRANITE This very coarse-grained granite may be a pegmatite, depending on the minimum grain size required to apply such a term. Again we have potassium feldspar, mostly yellow, with some turquoise grains of amazonite, a potassium feldspar variant [turquoise arrows]. Quartz [mauve arrows] shows up as typical grey, glassy grains without any cleavage faces. The flaky black grains are biotite. EXTRUSIVE IGNEOUS ROCKS With the rapid cooling of lavas that occurs at the Earth’s surface, much smaller crystals form, or in some cases, no crystals form at all. This is a tremendous obstacle to identification in hand specimen, and in practice one is heavily dependent on the overall colour of the rock as a guide to its composition, and thus probable mineralogy. There may be useful clues in the rock that will point you to the mineralogy, even if no specific minerals can be identified with the tools at your disposal, and some of these will be featured in the following images. BASALT This typically dark, mafic to ultramafic volcanic rock is apparently featureless. The presence of olivine suggests it is ultramafic. The dark colour suggests this is mafic, and we note the occasional green glint from slightly larger olivine crystals [green arrows]. Olivine is found only in ultramafic and mafic rocks, rarely with plagioclase but frequently with pyroxene, which we therefore surmise is also present. BASALT – With or Without Useful Clues As with the previous image, the sample on the left exhibits a few slightly larger olivine crystals [green arrows], and probably has pyroxene as the other mineral. In the right sample, the purple arrows point to amygdules, which are minerals precipitated in once-empty vesicles. Given that they may have formed well after the lava cooled, and be unrelated to it, they are no indicator of the lava’s composition. BASALT – Clues in Vesicular Basalts The scoria, or scoriaceous basalt, on the left has a few clues to its chemistry. Many of the vesicles have a lining of pale pea-green material [green arrows] often derived from the weathering of olivine, and the iron content is confirmed by the reddish-brown oxidized (rusted) weathered surface [red arrows]. The right sample has obvious olivine crystals, perhaps phenocrysts, but no lining to the vesicles. BASALT – Pillow Basalt from a Mid-Ocean Ridge Submarine eruption of basalt lavas leads to very rapid cooling of the exterior surface, to produce a flexible skin that contains the lava. Successive eruptions look like a stack of pillows, with rounded, convex upper surfaces. On the left we see the fresh surface (broken and also cut with a rock saw) with the yellow arrows pointing to the rapidly weathered exposed surface, seen on the right. COLUMNAR BASALT This outcrop is the Giant’s Causeway in Ireland; the Devil’s Post Pile is a similar exposure in California. The polygonal columns result from cooling, contraction, and cracking of thin, widespread sheets of mafic rock. These occur either by subaerial eruption of fluid basalt at rifts within continents, or by intrusion of mafic magma as near-surface sills between layers of cooler sediments. BASALT This is a porphyritic basalt, whose phenocrysts tell us much about the composition. The plagioclase phenocrysts [red arrows] suggest this is mafic, not ultramafic. As such, the matrix between the phenocrysts is likely a mixture of pyroxene and plagioclase, without any appreciable olivine. TRACHYTE – an Intermediate Volcanic Rock The classic intermediate composition volcanic rock is andesite. These samples, from the Crowsnest Pass, are alkali-rich (K, Na) intermediate rocks, whereas true andesite would be higher in Ca. The black phenocrysts are garnet [yellow arrows], with dodecahedral habit (the mafic minerals in intermediate rocks are more typically amphibole or pyroxene). The pink phenocrysts [blue arrows] are feldspar. RHYOLITE The lighter colour is indicative of the felsic composition of this extrusive rock, though we cannot distinguish the minerals. We expect, based on its felsic composition, that it would have quartz and potassium feldspar, and perhaps some mafic mineral content. The black spots [red arrows] are in fact not mafic minerals, but small blobs of black volcanic glass, or obsidian, which itself is felsic. RHYOLITE This would normally be called pumice, a term that describes the texture rather than being a proper rock name used in classification. It represents a case in which gas-rich felsic lava has turned into a sort of sticky froth that has eventually hardened. Flow of this taffy-like material has produced many glassy strands spanning the vesicles [blue arrows]. It is otherwise like the previous sample. OBSIDIAN This rock would have erupted as a rhyolite lava in the form of pumice, then collapsed. Rocks have minerals, which are crystalline, yet this is felsic volcanic glass, and is an exception to the basis for colour index. There are no mafic minerals (or, technically, any other for that matter), so this rock has a Colour Index of zero, even though it is completely black on the fresh surface. The brown weathered surface is a clue to the presence of iron, dispersed through the glass to make it black.