Froeb_23 - Vanderbilt Business School

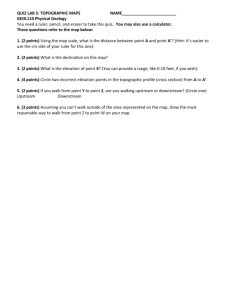

advertisement

Chapter 23: Managing Vertical Relationships Managerial Economics: A Problem Solving Appraoch (2nd Edition) Luke M. Froeb, luke.froeb@owen.vanderbilt.edu Brian T. McCann, brian.mccann@owen.vanderbilt.edu Website, managerialecon.com COPYRIGHT © 2008 Thomson South-Western, a part of The Thomson Corporation. Thomson, the Star logo, and South-Western are trademarks used herein under license. Slides prepared by Lily Alberts for Professor Froeb Summary of main points • Do not purchase a customer or supplier merely because that customer or supplier is profitable. There must be a synergy that makes them more valuable to you than they are to their current owners. And do not overpay. • If unrealized profit exists at one stage of the vertical supply chain — as often happens when regulations limit profit — a firm can capture some of the unrealized profit by vertical integration, by tying, by bundling, or by excluding competitors. • The double-markup problem occurs when complementary products compete with one another. Setting prices jointly eliminates the double-markup problem and is often a motive for vertical integration or maximum price contracts between a manufacturer and retailer. Summary of main points (cont.) • Restrictions on intra-brand competition like minimum resale price maintenance or exclusive territories provide retailers with higher profit, giving them incentives to provide demandenhancing services to customers. • If a product has two retail uses, a manufacturer may find it profitable to integrate downstream so that the firm can capture the profit through price discrimination. Vertical integration stops arbitrage between the two products, which allows price discrimination. • Outsource an activity if the outsourcer can perform the activity better or more cheaply than you can. Intro. anecdote: UC Power & Light • UC P & L sells electricity to customers at rates regulated by the state Public Utility Commission. • UC P & L is allowed to earn a nine percent return on invested capital. • The UC decided to buy the mine that supplies them with coal. • They formed a multi-divisional company, a regulated Power division, and an unregulated Coal mine. • By raising the transfer price of coal sold to the Power Division, they Coal division evade the regulation that limits profit for the Power division. • An increase in the price of coal raises the marginal cost of producing electricity (and Coal profit). • Under the profit regulation, this allows the Power Division to raise electricity prices. Introductory anecdote (cont.) • As a result, Coal earns more on the coal it sells; and Power is allowed to raise the regulated price of electricity so that its profit does not fall. • In other words, the Coal Mine is more valuable as a sister division to the Power Company than it is as an independent company. • This chapter looks at vertical relationships (merger, or contracts) between upstream suppliers and downstream customers in same vertical supply chain. • Vertical relationships can increase profit by giving firms a way to evade regulation, eliminate the double-markup problem, better align the incentives of manufacturers and retailers, and price discriminate. Caveat: Beware Acquisitions • Do NOT buy a customer or supplier simply because they are profitable • Purchasing a profitable upstream supplier or downstream customer will not necessarily increase your profit. • Without some kind of synergy, the value of the upstream supplier or competitor is exactly equal to the size of its profit stream – not moving assets to higher value uses. • Discussion: In 1999 AT&T bought TCI’s cable TV assets for $97 B; then in 2002, they sold the cable assets to Comcast for $60 B. Evading Regulation • One of the simplest and easiest-to-understand reasons for vertical integration is to evade regulation. • If unrealized profit exists at one stage of the vertical supply chain — as often happens when regulations limit profit — a firm can capture some of the unrealized profit by integrating vertically, by tying, by bundling, or by excluding competitors. • Discussion: How can you evade Rent Control (HINT: Tying, bundling, or exclusion) • Discussion: How can Multi-National companies evade national taxes using transfer pricing? Solving the Double-Markup Problem • Discussion: Gasoline refiners selling branded gasoline • This problem can be analyzed more generally as a prisoners’ dilemma faced by any two firms in the same vertical supply chain or by any two firms selling complementary goods. • In this case, consumers demand the gas, as well as the retail outlet that dispenses it. • When firms selling complementary products compete with each other, they price too high. • The double-markup problem occurs when firms selling complementary products set price in competition with each other. • Vertical integration is one way of addressing the double marginalization problem – commonly owned firms can coordinate more easily on lower prices to raise profit. Aligning Retailer Incentives with Manufacturer Goals • Discussion: Getting retailers to invest in demand-enhancing services • With a smaller profit slice, retailers may under-invest in services that help enhance a brand name. • Intra-brand competition can be controlled by means such as granting exclusive territories, or setting minimum retail prices. • This guarantees retailers a higher profit level creates incentive to provide demand-increasing services • Can you think of examples of this? • Limiting intra-brand competition also helps reduce free-riding, e.g., PING golf clubs require custom fitting and are not sold over the Internet. • BUT, many of these tactics may be illegal under antitrust laws • Especially for companies with dominant market shares Aligning incentives (cont.) • Frequently, practices that limit distribution in an attempt to enhance demand for a brand may violate anti-trust laws. • For example, European authorities have prohibited Coke from purchasing refrigerators for retail outlets because the practice may unfairly exclude rival soft drink manufacturers from retail outlets. • In Europe this is known as “abuse of dominance” and in the US as “monopolization” or anticompetitive “exclusion.” • To avoid this, remember: If you have significant market power, you should consider the effect any planned action will have on competitors. Price Discrimination • Vertical integration of downstream products can make it easier to price discriminate. • When there are two separate consumer groups who use the same product in different manners, buying a retailer can make it easier to price discriminate in a way that wont be defeated by arbitrage. • Example: Herbicide users • Home gardeners are willing to pay $5 per liter for herbicide. • Farmers are willing to pay $3 per liter. • Vertical integration solves the pricing dilemma by preventing farm retailers from selling to home gardeners. • Price discrimination at the consumer level is legal; but at wholesale level is more difficult (and may be illegal). Outsourcing • While technically the opposite of vertical integration, decisions to outsource should employ the same logic as decisions to vertically integrate. • Outsource an activity to an upstream supplier or downstream customer if they can do it more profitably. • The typical reason to outsource is to gain advantages of economies of scale or scope. • Remember to consider whether you are sacrificing any integration benefits before you decide to outsource. • Outsourcing takes away control of upstream manufacturing processes or downstream distributors and retailers. • It may also create a double-markup problem; you may find it difficult to motivate your downstream customers or upstream suppliers to invest in activities that benefit you; and you may find it more difficult to price discriminate. Alternate Intro Anecdote • The Aluminum Company of America (Alcoa) was the only domestic supplier of aluminum ingots prior to 1930, which were used for a variety of purposes • An addition to the production process in the iron and steel industry, used to improve the quality of the final product. • Manufacture of cooking utensils • Production of electric cable • Automobile and aircraft parts constituted the final two end markets. • Consumers in these diverse markets varied widely in their willingness to pay for aluminum ingots. • Demand for aluminum in the iron/steel industry and in the aircraft industry was relatively inelastic • In the other three industries, demand was much more elastic Alternate Intro Anecdote (cont.) • The potential for arbitrage created a barrier to implementing a scheme to increase prices to iron/steel and aircraft consumers while generally reducing price to the other three markets. • To successfully implement its price discrimination scheme, Alcoa was forced to forward integrate into the three relatively elastic markets. • By moving into the cookware, electric cable, and automotive parts markets, Alcoa prevented potential re-sale of aluminum ingot and was able to maintain high prices to the iron/steel and aircraft parts markets. 1. Introduction: What this book is about Managerial Economics 2. The one lesson of business 3.Benefits, costs and decisions Table of contents 4. Extent (how much) decisions 5. Investment decisions: Look ahead and reason back 6. Simple pricing 7.Economies of scale and scope 8. Understanding markets and industry changes 9. Relationships between industries: The forces moving us towards long-run equilibrium 10. Strategy, the quest to slow profit erosion 11. Using supply and demand: Trade, bubbles, market making 12. More realistic and complex pricing 13. Direct price discrimination 14. Indirect price discrimination 15. Strategic games 16. Bargaining 17. Making decisions with uncertainty 18. Auctions 19.The problem of adverse selection 20.The problem of moral hazard 21. Getting employees to work in the best interests of the firm 22. Getting divisions to work in the best interests of the firm 23. Managing vertical relationships 24. You be the consultant EPILOG: Can those who teach, do? 15