Supported Accommodation Facilities (SAFs) Report

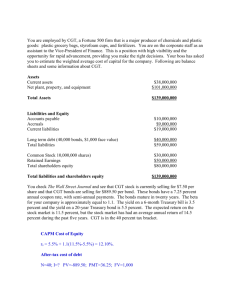

advertisement