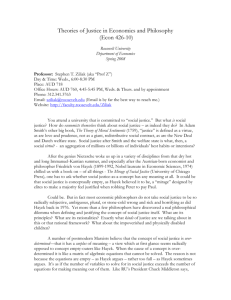

Late Development and Industrial Policy - TPP-PED

advertisement

Week 13: The State and Development: Growth Strategies and Late Industrialization in Developing Countries DEFINITIONS: Late Developing Countries: Developing in a time when others are more technologically advances, efficient, incumbent countries. Late industrialisation: How ‘missing’ prerequisites in latecomers are created or substituted (in the very course of development and industrialisation) through SPECIFIC INSTITUTIONAL RESPONSES. The Infant-Industry Model (Rapley, 2007) List = states needed to protect and nurture their economies until they caught up with Britain, only then could the world open up to unregulated competition. Focus on STATISM and time-limited PROTECTION – shares characteristics with ISI – both are founded on the principle that conditions in the developing world are so vastly different from those in the developed world that NC model cannot be used to develop an economy whose conditions call for state intervention. To raise industry requires sums of capital beyond reach of private financial sector – state can gather through borrowing, taxation and sale of exports. Further, to build up human capital state must invest heavily in education. To acquire, adapt and alter production technologies imported from developed world, firms must be given a LEARNING PERIOD during which the state protects from foreign competition. To make it possible for firms to move onto a market in which penetration and brand loyalty favour established producers, the state may have to RESERVE ITS DOMESTIC MARKET for a set period of time = THE STATE CAN LEVEL THE PLAYING FIELD BETWEEN DEVELOPING AND DEVELOPED WORLD. How different from ISI? 1. Rather than build an industrial base to satisfy local demand, it focuses on building an economy’s export industries. 2. Rather than provide local industry with indiscrimate protection, governments in IIM ‘choose winners’ – selecting a few industries to nurture and relying on imports to satisfy remainder of local demand. This model seeks to FOSTER NEW COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE = dynamic rather than static comparative advantage. This should all be market-enhancing i.e inefficient firms left to die – in countries which practiced ISI this was seldom done – MUST IMPOSE DISCIPLINE ON PRIVATE ENTREPRENEURS. Also important to note that rural-urban transfer is not necessarily a zero-sum game = both South Korea and Cote d’Ivoire used surpluses from their agricultural sector to fuel rapid expansion in urban industry (need to develop primary sector as well – ISI often failed to do this) Gains of development need to be distributed broadly = creates a large class of consumers with moderate incomes = demand for narrow range of products/specialisation = may take advantage of economies of scale. Problem with ISI was that it concentrated gains of development in urban sector = resulted in uneven distribution of land and income – this is why DS theorists advocate land redistribution as a key ingredient in development – need a very hard state to do this as makes enemies of privileged populations. Import Substitution Industrialisation ‘The logic underlying ISI is simple. Let us assume that a given country is exporting primary goods in order to import finished goods. It wants to begin processing those finished goods itself. It can do this by restricting imports of the goods in question by way of tariffs – taxes on imported goods – or of nontarrif barriers such as quotas, content regulations, and quality controls. Such restrictions raise the prices of imported goods to local consumers – local investors who could not previously compete with the foreign suppliers find the market benign. Because third-world producers operating in an ISI regime cannot exploit economies of scale (due to small domestic market), the prices on their goods will be higher than those on the world market. Nevertheless, provided these prices remain below the administratively inflated prices of imports, any venture can turn a profit’ (Rapley) Import substitution industrialization or "Import-substituting Industrialization" (called ISI) is a trade and economic policy based on the premise that a country should attempt to reduce its foreign dependency through the local production of industrialized products. The term primarily refers to 20th century development economics policies, though it was advocated since the 18th century. It has been applied to many countries in Latin America, where it was implemented with the intention of helping countries to become more self-sufficient and less vulnerable by creating jobs and relying less on other nations. The ISI is based primarily on the internal market. The ISI works by having the state lead economic development through nationalization, subsidization of vital industries (including agriculture, power generation, etc.), increased taxation to fund the above, and highly protectionist trade policy. Some of the positive effects of ISI included increased jobs and a more stable state. Ultimately, the ISI model was exhausted, because the size of internal markets were too small. As a result, there were fewer people buying products in the industrial market. Further, countries could not easily delink themselves with other countries and depended very much on exports, imports, and multinational corporations. Adopted in many Latin American countries from the 1930s until around the 1980s, and in some Asian and African countries from the 1950s on, ISI was theoretically organized in the works of Raúl Prebisch, Hans Singer, Celso Furtado and other structural economic thinkers, and gained prominence with the creation of the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (UNECLAC or CEPAL). Insofar as its suggestion of stateinduced industrialization through governmental spending, it is largely influenced by Keynesian thinking, as well as the infant industry arguments adopted by some highly industrialized countries, such as the United States, until the 1940s. ISI is often associated with dependency theory, though the latter adopts a much broader sociological outlook which also addresses cultural elements thought to be linked with underdevelopment Conceptually, ISI could be outward-looking in that it promotes exports (like in Asia, especially South Korea) or inward-looking without significant links to world markets (like in Latin America). The decision to adopt one or another perspective is frequently determined by external factors. The industrialization of South Korea and other Asian Tigers, for example, was in line with the United States's geopolitical strategy of building a "contention belt" of capitalist countries around China and other communist states in Asia, which involved the granting of incentives for these countries to export to the United States. In contrast, Latin American countries, which were outside the main areas of geopolitical concern, did not receive these incentives – despite requests that they be extended to them, for example in the Pan-American Operation proposed by Brazilian President Juscelino Kubitscheck. Consequently, Latin American countries concentrated on producing for their domestic markets, or on building expanded areas which could absorb scale-production, such as the Latin American Free Trade Association (ALALC) and the Latin American Integration Association (ALADI), which were never fully implemented. Both in inward and outward-oriented ISI, however, external competition by imports in the markets of the targeted industries are discouraged, by tariffs, devalued currencies and other factors. Hence, policies to pursue ISI have a strong protectionist component and are not favored by advocates of absolute free trade. Export-orientated industrialisation Export-oriented Industrialisation (EOI) sometimes called export substitution industrialisation (ESI) or export led industrialization (ELI) is a trade and economic policy aiming to speed-up the industrialisation process of a country through exporting goods for which the nation has a comparative advantage. Export-led growth implies opening domestic markets to foreign competition in exchange for market access in other countries. However this may not be true of all domestic markets, as governments may aim to protect specific nascent industries so they grow and are able to exploit their future comparative advantage and in practise the converse can occur. For example many East Asian countries had strong barriers on imports during most of the 1960s-1980s. Reduced tariff barriers, floating exchange rate (devaluation of national currency is often employed to facilitate exports), and government support for exporting sectors are all an example of policies adopted to promote EOI, and ultimately economic development. Exportoriented Industrialisation was particularly characteristic of the development of the national economies of the Asian Tigers: Hong Kong, South Korea, Taiwan and Singapore in the post World War II period ESSAY QUESTION: What are some of the main economic and political challenges in implementing effective industrial strategies? EXAM QUESTIONS: ‘Industrial policy in late developers is as much a political as an economic challenge’. Discuss. ‘The prospects of late industrialisation are poor without effective state intervention.’ Discuss. Critically assess the claim that trade liberalisation and a realistic exchange rate are the key to faster growth in less developed countries. “Developing countries need foreign capital and technology; therefore, they should always welcome foreign direct investment”. Discuss. ‘Reducing levels of corruption in low-income countries is effective in inducing faster economic growth’. How convincing is this argument? Corruption is routinely measured to be far higher in developing countries than in richer industrialised economies. What explains this and to what extent does this create a substantial obstacle to economic growth? ‘Corruption and rent-seeking are obstacles to economic development.’ Discuss. Explain why corruption and rent-seeking can have very different implications in late developers. Lecture Blurb: This lecture will focus on the problem of late industrialization and its relationship to economic nationalism in historical perspective. It will consider the variety of political/economic paths to industrial development as well the logic of industrial policy and the developmental state. This unit also reviews the most important growth and accumulation strategies implemented in LDCs, particularly the contrast between importsubstituting industrialisation and export-oriented industrialisation It will also cover the political and economic implications of late development for the current debates on governance. Key Themes from the lecture: Alexander Hamilton – architect of US industrial policy. Earliest use of the concept of ‘Infant industry’— argued that technologically inferior agrarian economy would never catch up with advanced European producers without government, support. Manufacturing important part of catch up. Tariffs and subsidies were therefore instrumental to the development aims of the American state. Highlighted that free trade is only beneficial under certain circumstances Agrees with Adam Smith on the theoretical virtues of free trade but….“If the system of perfect liberty to industry and commerce were the prevailing system of nations, the arguments which dissuade a country of in the predicament of the US from the zealous pursuit of manufacturers would, doubtless, have, great force.” The country, however, faces a “situation, not a theory.” As a result, from the 1970s onwards, the US maintained the highest level of tariff protection at that time (cf Chang (2002) – kicking away the ladder Chp 2). ‘DO WHAT WE SAY, NOT WHAT WE DID’ First systematic analysis of late development – trying to catch up with Britain. Influence on policy makers in Japan and France – important role of the state in protecting industry and development. Important role of the state to protect infant industry Influenced Frederick List –The National System of Political Economy (1841). “In order to allow freedom of trade to operate naturally, the less advanced nations must first be raised by artificial measures to that stage of cultivation to which the English nation has been artificially raised.” (131). 3 Rules of Development: Kaldor 1967 All countries develop and sustain high per capita incomes through industrialisation Most infant industries develop through protection Anyone who says otherwise is lying Very different from the discourse today which promotes: Free trade Lower level of state interventions The promotion of free markets. Rich countries preaching a different story to their own. Late Development (Gerschenkron (1962)): Basically, looked at 3 different countries (Britain, Germany and Russia) which were all at very different stages of development. 1. Crucial feature —latecomers different from forerunners because they are late. Laterunners different from forerunners because they develop in the context of more productive incumbent firms and economies 2. Organizing concept: Degree of backwardness is (distance from technological frontier—income per capita or productivity levels). n.b. degree of backwardness is measured as distance from efficient producers – income per capita is one way to measure this, but countries may have high per capita income in oil rich countries e.g. but actually very fare behind re technological advancement – therefore, good idea to look at productivity levels in manufacturing sector. 3. --"late development" presented the challenge of accommodating the relation between technological factors (large-scale production) with institutional factors (underdeveloped capital markets). Basically the challenge of setting up new large firms when banks don’t have the capacity to write loans etc. 4. catching-up occurs by undertaking more capital-intensive investment in individual PLANTS—even though overall capital intensity of the backward economy is less. LDCs are labour-surplus economies so how do they go against comparative advantage to develop? = capital intensive plants in a context of financial systems unwilling to invest in long-run investment e.g. setting up steel plant has large fixed set-up costs where the return on investment is gestated – LONG-RUN VIEW = very risky in LDC because economy is so thin it’s difficult to make long-run bets. Characteristics of late development: Late Development—not simply a process of transfers (of technology and institutions) but a process of DEVISING FUNCTIONAL SUBSTITUTES. Late industrialization - how ‘missing’ prerequisites in latecomers are created or substituted (in the very course of development and industrialisation) through SPECIFIC INSTITUTIONAL RESPONSES. For example, differences in the way that Britain, Germany and Russia developed (see below). Initial conditions (human capital, bureaucratic quality, low corruption)—are as much by-products of growth strategy as inputs. Vs. GG arguments. Questions the Prerequisite View of Development. Country: Institutions funding development: Britain Germany Stock market funded long term industrial projects Financial sector not as developed therefore cannot fund development. Investment banks largest funders – functional substitute to the stock market. Russia Therefore stage of economic development very important to the types of institutions present in a country – vs. GG one size fits all development model of institutions. When countries begin developing, v. important to the types of institutional forms underlying capital accumulation. Largely peasant economy. Neither stock market now investment banks developed – state development bank played the crucial role, only institution with the resources available for long-term investment. Therefore was the functional substitute. The logic of subsidy of Infant Industry in late developers: Needed for four reasons. Backward institutional environment/infrastructure—implicit subsidy to producers in more advanced countries (first-mover advantage). Entrepreneurs in developing countries start up in institutionally backwards areas (Infrastructure works, skills available etc) – leads to higher TC’s. Amsden and Hikino – Measures of backwardness – much greater challenge in post WWII era than 19th Century Germany. Learning-by-doing (Arrow, 1962) – requires time and means that producers in LDC’s at disadvantage since earlier developers have more experience. Infant industries are less efficient; cheap labour (low wages not a basis for competition) therefore not sufficient to overcome gap in productivity. Asset-specific firm investments (reputation, branding – cash reserves for advertising etc) over time generate rents for firms with experience – signals quality that develops over time. Large fixed set-up costs (economies of scale important) therefore it’s a long time before you see a return on your investment. Particular challenge in developing countries because the financial sector is not able to commit. Late Development (especially Late Industrialization) is inherently RISKY, especially in the context of free trade. Role of the State: Socialize Risk and Induce Risk Taking and Learning. For example: Tariff protection (imported products set at a higher price for consumers) Non-Tariff borders – Banning imports Subsidised credit Subsidised imports – cheap electricity, subsidised fertiliser Provision of infrastructure Functional Substitutes in 20th Century Late Developers: The rise of latecomers in the 20th century—based for the first time on industrialization without proprietary innovations. Late industrialization as pure learning. This dependence lent the process of catch-up its distinctive norms: New Control Mechanism -principle of reciprocity (support/discipline by the state). In return for support, state had to discipline firms e.g. if inefficient industry state withdraws support. Selectivity—Industrial Policy is aimed at particular industries (and firms as their components) to achieve the outcomes that are perceived by the state to be efficient for the economy as a whole. Exports need to move away from commodities (volatile) into areas of greater technology. Therefore selective late industrial states (Japan/South Korea) selective in their support. Large and concentrated firm size key to competitiveness: Large diversified business group initial agent of industrialization. E.g. Industry/Plant set-up needs to be of a scale which it can at some point grow up and be able to compete on it’s own. Gives the opportunity to pool risk if you concentrate investment (can also capitalise on scarce talent) – can take profits to cross subsidise another sector e.g. Samsung/Hyundai. Key: Tariffs most fiscally feasible way for late developers to develop historically. Doesn’t cost the state money, unlike subsidised credit – often there is not already an established tax base therefore adds needed revenue. However, they have been removed as tools for poor countries to deploy. Developmental states predicated on the following functions to socialise risk and induce learning: 1. Development banking 2. Local-content management – state used to bargain with multinationals for example, increasing use of domestic supply parts to increase profits – trying to promote domestic industry. 3. “Selective seclusion” (strategic integration) – looking at sectors which were historically important for development and supporting them in your own country – e.g. textiles. (If you promote every sector, incentives not there for investors to move into the areas you want – channelling of entrepreneurial talent/resources into strategic sectors). 4. National firm formation - Promoting particular forms within these sectors, e.g. Finland, Sweden. Netherlands. 5. Greater role of SOE (state owned enterprise) in production – state the only one able to find the resources to support certain areas e.g. railways, mining. The developmental state – Woo-Cummings (1999). For example, airbus example of large subsidies needed to break into aero industry, Japanese car industry turned down loan by WB for a large amount of time – Likely to make large losses for years. Profitability of firms therefore not an accurate indicator of whether it is moving in the right direction, you can suddenly turn a corner from large losses into highest success in industry. Key point is which states are able to create exit strategies/discipline unproductive and inefficient firms. Suspending forces for competition through protection. Neoclassical economics is a methodology – Hayek (1945), critical article. Forefather of IE. Market creates valuable information through prices, ex-post (to the process of investment) and rivalry/competition. Infant Industry – suspending information and disciplinary role of markets, therefore the ability of the state to manage this process is very important. Why are some countries more successful in implementing industrial policy and others aren’t? Analysis of why it doesn’t work not comprehensive (Chang). Labour exploitation, social factors, gender imbalances etc generate different industrial policies. Political Economy of Rents and Rent-Seeking: 1. Rents = monopoly profits = SUBSIDY Above average profit rate e.g. monopoly, v. valuable therefore likely to induce rent seeking: including legal (lobbying) and illegal (bribery) forms. Taking place in countries where state purposely creating rents. Most countries don’t have the bureaucratic capacity to ensure that this doesn’t collapse (WB) – have to look at cost but also benefits created. 2. Rents RISKS 3. Rent-Seeking – Influencing Activities to maintain, create and change rights. 4. Rent outcomes – Net benefits associated with the maintenance, change and creation of rights. 5. IMPORTANT CONDITIONS TO UNDERSTAND THE EFFECTS OF RENT-SEEKING AND STATE-CREATED RENTS: Motivations of leaders – looking for long-term industrial development or short-tem profits? Performance Criteria, Disciplinary Power of the State – political process disciplining? What are the historical origins leading to why some states are successful whilst some are not? Selectivity of Rent Development – distributional advantages to some and others not. Maintaining political stability, e.g. Senegal (Boone) v.s. S. Korea – more people to please in Senegal. Therefore infant industry protection not taking place. Security of Growth-enhancing property rights. Weakness of Gerschenkron’s late development analysis: Gradual catching-up not considered (e.g. Nordic countries) – focus on heavy industry. Role of the state in enforcing property rights taken for granted (no functional substitute no for effective governance of the state.) – no political analysis. ‘Big-push’ overexpansion led to problem of overheating through debt-led growth – neglected. Underestimated geo-political and political economy factors. Why are some countries more focused on industrial development? Role of the external threat of communism gave some the capacity o be disciplinary – e.g. S. Korea. Discipline of Rent Recipients and Selectivity Serve Economic Functions but require POLITICAL ANALYSIS to understand where the power of the state to develop and enforce these functions originates. As Amsden (2001) notes: “That conditions of ‘lateness’ are inherently conducive to overexpansion is suggested by the fact that when a debt crisis occurs, it almost always occurs in a latecomer country.” This is because…diversification in the presence of already well-established global industries involves moving from labour-intensive to capital-intensive sectors characterized by economies of scale.” (p. 252). The scale of “big push” investments were, indeed, instrumental in the debt crises in Latin America in 1982 and in East Asia in 1997 as both were preceded by a surge in investment (ibid. p. 253). Of course, the duration of a crisis will depend on the capacity of the state to effectively change institutions so as revive investment, growth, competitiveness and exports. In this respect, East Asian developmental states were more successful than their Latin America counterparts (ibid.) Weiss and Hobson (1995) States and Economic Development—Gershenkron neglected to ask why industrialization became a strategy and where and how the capacity of the state emerged. Underestimated geo-political factors, particularly the THREAT OF WAR as crucial. Similar to Tilly on war and state-making and tax collection – threat of war/political obliteration enabled taxes to be collected to raise an army. Conflict/violence can be developmental. See Kohli, A. 2004. State-Centred Development. Cambridge University Press. Industrial Policy Options – (Lin and Monga) Because many LDCs are likely to have limited state capacity to intervene effectively, it is essential that states target industries that are not overly ambitious in terms of technological challenges. This means targeting industries that have relatively simple technologies and are relatively labour-intensive. Labour intensive industry is important in the creation of employment. Industrial strategies that have targeted complex heavy industries have often been a failure (Di John, 2009; Lin and Monga, 2010). A common feature of the industrial upgrading and diversification strategies adopted by successful countries (the most advanced ones and the East Asian NIEs in the post-war period) was the fact that they targeted mature industries in countries not too far advanced compared to their own levels of per capita income (Lin and Monga, 2010). It pays for LDCs to examine the industrial experiences of countries that have certain similarities to their own. That may have been the single most important cause for their success. Pioneer countries always played the role of an “economic compass” for latecomers: 16th century Netherlands played that role for Britain, which in turn served as a model and target to the U.S., Germany, and France in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and to Japan in the mid 20th century. Likewise, Japan was imitated by Korea, Taiwan-China, Hong Kong-China, and Singapore in the 1960s and 1970s. Mauritius picked Hong Kong-China as its “compass” in its catch-up strategy in the 1970s. China chose Korea, Taiwan-China, and Hong Kong-China in the 1980s. For example, the strategy for SSA may therefore be to look at countries a little more advanced than them e.g. Vietnam and seeing what their import structure looked like 30 years ago to find areas to focus on. Key is to not be too ambitious (e.g. through unsustainable heavy industry). For example, US wrong model to follow for Latin America – not a late developer with different types of institutions. Case-Study Example, Mauritius: An example of this comes from Mauritius, one of the most successful African economies, which took off in the 1970s by targeting labour-intensive industries such as textiles and garments. These industries were mature in Hong Kong, its “compasseconomy” (Lin and Monga, 2010). Both economies share the same endowment structure and the per capita income in Mauritius was about half of that in Hong Kong-China in the 1970s. The Mauritius Industrial Development Authority (MIDA) and Export Processing Zones Development Authority were created by the government to attract Hong Kong-China’s investment in its export-processing zone. The vision was to position Mauritius as a world class export hub on the Hong Kong-China model. Together, they have contributed to the country’s emergence as a successful late developer. Foreign firms are likely to play a more important role in the industrialization compared to earlier late industrialisers. This is both because their degree of backwardness is greater and because the domestic private sector is likely to be weak. As such, developing joint ventures may be promising (e.g.Bangladesh garments industry a mixture of joint ventrues) In LDCs with poor infrastructure and a difficult business environment, the government can invest in industrial parks or export processing zones and make the necessary improvements to attract domestic private firms and/or foreign firms that may be willing to invest in the targeted industries. Greater efficiency by targeting territorial areas/industrial clustering e.g. Silicone Valley. NB: Improvements in infrastructure and the business environment can reduce transaction costs and facilitate industrial development. However, because of budget and capacity constraints, most governments will not be able to make the desirable improvements for the whole economy in a reasonable timeframe. Focusing on improvement in infrastructure and business environment in industrial parks or export processing zones is, therefore, a more manageable alternative. Industrial parks and export processing zones also have the benefits of encouraging industrial clustering (Lin and Monga, 2010). Given that electricity provision is one of the main contributors to light manufacturing production and exports (UNCTAD, 2006), donors should prioritise this within the package of aid to infrastructure. Aid switched away from economic to governance/social provision. Not necessary good for development – finite source. While much of the World Bank advice has been to limit industrial policy as a tool of government intervention, there is still substantial room for donors to contribute to improving the interventionist capacity of states in the area of industrial policy. The reality is that most less developed countries still engage in some form of industrial policy (Rodrik, 2004). One useful and relatively inexpensive approach might be to encourage South-South cooperation. For instance, it may be worth trying to persuade relatively successful industrial policy states (e.g. South Korea, Malaysia, Brazil) to be share lessons of successful interventions when those countries were at earlier stage of development with LDCs. In particular, strengthening capacities in ministries of industry and planning would be useful. Industrial Policy as Discovery Process where learning takes place (Rodrik and Hausmann): “The conventional approach to industrial policy consists of enumerating technological and other externalities and then targeting policy interventions on these market failures. The discussion then revolves around administrative and fiscal feasibility of these policy interventions, their informational requirements, their political economy consequences, and so on… The task of industrial policy is as much about eliciting information from the private sector on significant externalities and their remedies as it is about implementing appropriate policies…. Correspondingly, the analysis of industrial policy needs to focus not on the policy outcomes—which are inherently unknowable ex ante- but on getting the policy process right. Latin America better governance than East Asia but not necessarily beneficial for industrial policy; trade offs apparent in late development process. We need to worry about how we design a setting in which private and public actors come together to solve problems in the productive sphere, each side learning about the constraints faced by the other, and not about whether the right tool for industrial policy is, say, directed credit or R&D subsidies or whether it is the steel industry that ought to be promoted or the software industry. Hence the right way of thinking of industrial policy is as a discovery process —one where firms and the government learn about the underlying costs and opportunities and engage in strategic coordination; centralised industrial policy requires co-ordinated decisions e.g. building up steel industry and railway. The traditional arguments against industrial policy lose much of their force when we view industrial policy in these terms.” But how can you use this? Why does it matter? Kholi, Di John. State still central to economic performance in the context of globalisation State as ultimate guarantor of property rights (no functional substitute for effective governance of the state) Investment is still mainly domestic Role of the state in taxation and resource mobilisation Role of the state in conflict resolution Still low levels of labour mobility and migration Different approaches: S. Korea, Taiwan (state owned heavy industry) and Malaysia within centralised approach. Compatibility of Development Strategy and Political Structure: Centralised Heavy Industrial Policy requires state co-ordination, selectivity and discipline - This policy works where state is co-ordinated and political fragmentation is low (South Korea, Taiwan, Malaysia). Centralised Heavy Industrial Policy fails in fragmented states/polities (India, 1960-1980; Pakistan, Venezuela) since co-ordination selectivity and discipline more difficult. Most countries have fragmented politics, often decentralised. Authoritarian not necessary. If you use compatible policies, you can still succeed – fragmented regionally based political structures don’t require heavy industry production. Decentralised, smaller-scale labour-intensive manufacturing can work even in fragmented, corrupt political systems (Thailand, Colombia, Italy) since centralised state co-ordination not required. Compatibility between political structures and development strategies employed therefore have done well. E.g. India – decentralised policy planning has increased growth e.g. c.f. 60s and now. Compatible with regional politics. Higher Wage regions (Latin America, Eastern Europe) cannot easily compete in cheap labour-intensive manufacturing so the case for industrial policy to promote large-scale industry is still strong. Have to look at why there is failure in some countries and success in others! See Khan and Jomo (eds.), Rents,Rent-Seeking and Economic Development CORE READINGS 1. Gerschenkron, A. 1962. Economic Backwardness in Historical Perspective. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. (chap 2, p. 31-51 essential as well), Pages: 5-30. Our thinking about the industrialisation of backward countries is dominated – consciously or unconsciously – by the grand Marxian generalisation that it is the history of advanced or established industrial countries which trace out the road of development: ‘The industrially more developed country presents to the less developed country a picture of the latter’s future’ (MARX, Das Kapital) We should be attempting to develop fully rather than stifle the ‘possibilities of things’ (KEYNES) In sum, exploring the ways in which the stage of development plays an important role in the types of institutions that play certain functions in financing capital accumulation. This goes against the GG agenda notion of one-size-fits-all – AngloAmerican model. Idea that capitalism has different forms and as such, this will affect the type of institutions (HALL has written about this in ‘Varieties of Capitalism’) See lecture notes above for detail. 2. Amsden, A. 2001. The Rise of the Rest: Challenges to the West from LateIndustrializing Countries. Oxford University Press. Chapter 1. Divide amongst ‘backward’ countries = ‘The rest’ (China, India, Indonesia, South Korea, Malaysia, Taiwan and Thailand, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Mexico, Turkey) to over-expand and fall into debt. The ‘remainder’ comprising countries that had been less exposed to modern factory life in pre-war period failed to achieve anywhere near the ‘rests success’- all about MANUFACTURING EXPERIENCE. Economic development is a PROCESS of moving from a set of assets based on primary products exploiting unskilled labour to a set of assets based on knowledge exploited by skilled labour. The TRANSFORMATION involves attracting capital (human and physical) out of RENT-SEEKING, COMMERCE, and ‘AGRICULTURE’ and into MANUFACTORING. KNOWLDEGE BASED ASSETS A KNOWLEDGE-BASED ASSET is a set of skills that allows its owner to produce and distribute a product at above prevailing market prices (or below market costs) – requisite skills are managerial and technological = production, execution and innovation capabilities. Idea that problem in backward economy is that there are too few KBAs, which leads to inability of these countries to compete at world prices even in industries that suit their capital and labour endowments e.g. textiles, steel, automobiles etc. Unlike information which is factual, knowledge is conceptual. It involves combinations of facts that interact in intangible ways – difficult to access whether by ‘making’ or ‘buying’. Perfection information is conceivable with enough time and money – a firm may learn all the facts pertaining to its business. Perfect knowledge is inconceivable because knowledge is firm-specific and kept proprietary as best as possible to earn technological rents. Economic theory and policy prescriptions related to economic development exist in relation to a cognition spectrum from accessible (Information – a stylised fact) and inaccessible (knowledge – combination of tacit and implicit ideas that form a firmspecific concept) – policies fall closer to accessible information. Heckscher-Ohlin-Samuelson trade theory, which still governs policy debates on economic openness = perfect knowledge (‘technology’) is a key assumption which renders firms in all countries in the same industry as equally productive, which leaves an uncompetitive country with only one efficient policy choice – adjust prices (reduce wages) rather than develop know-how (subsidise learning). NIE is perceived as a movement towards INCREASINGLY PERFECT INFORMATION, markets and thus minimal ‘transaction costs’ rather than a process of developing knowledge based assets to reduce production costs and enhance market position Problems of underdevelopment are linked to lack of information, not knowledge (financial markets for example fail in poor countries because they lack enough information about inexperienced borrowers) = gov policies remain focused on education and firm-neutral infrastructure Nature of technology makes knowledge difficult to acquire – difficult to determine KBA = difficult to copy, which leads to above normal profits = entrepenurial and technological rents. This leads to models of comparative advantage to not behave predictably i.e latecomers cannot industrialise simply by specialising in a low-technology industry Poor countries lower wages may prove inadequate against a rich country’s higher productivity A NEW CONTROL MECHANISM (as discussed in lecture) To compensate for skill deficit, ‘the rest’ devised an unorthodox original economic model – new because it was governed by an innovative control mechanism = a set of institutions that imposes discipline on economic behaviour. The control mechanism of ‘the rest’ revolved around the principle of reciprocity. Subsidies (intermediate assets) were allocated to make manufacturing profitable – facilitate flow of resources from primary product assets to KBA. Recipients of intermediate assets were subjected to monitorable performance standards that were redistributive in nature and results-oriented. RECIPROCAL CONTROL MECHANISM OF THE REST – transformed the inefficiency associated with government intervention into collective good = IDEA OF MINIMISING GOVERNMENT FAILURE. First of engineering experiments = FREE TRADE (export processing) ZONES – rationale behind this was that ‘the rests’’ manufacturers were intrinsically profitable at world prices given their low wages – to industrialise it was necessary to simply ‘get the prices right’ – free trade zones step in right direction = manufacturers detached from exchange rate distortions – all imported inputs were freed of duties – in exchange, firms had to export 100% of output. Development planners went even further – offered greater subsidies to textile industry and prospective mid-technology manufacturers – deliberate attempt to ‘get prices wrong’ in order to make manufacturing activity profitable. NATIONAL OWNERSHIP While all countries in ‘the rest’ succeeded in building mid-technology industries, some went further than others in becoming knowledge-based economies. China, India, Korea and Taiwan began to invest heavily in their own proprietary national skills, which helped them to sustain national ownership of business enterprises in mid-technology industries and invade high-technology sectors based on ‘national leaders’. By contrast, Argentina and Mexico and to a lesser extent Brazil and Turkey increased their dependence for future growth on foreign know-how. THAILAND’S RECIPROCAL CONTROL MECHANISM 3. Sheffadin, M. 2000. ‘What Did Frederick List Actually Say? Some Clarifications on the Infant Industry Argument’, UNCTAD Discussion Paper 149. pp.1-23. List recommended selective rather than across-the-board protection of infant industries and was against neither international trade nor export expansion = he envisages FREE TRADE AS AN ULTIMATE AIM OF ALL NATIONS. List’s theory is dynamic with dimensions of time and geography. Protection is necessary for countries at early stages of industrialisation if some countries ‘outdistanced others in manufacturers’. Protection should be TEMPORARY, TARGETED AND NOT EXCESSIVE. Domestic competition should be introduced in due course, preceded by planned, gradual and targeted trade liberalisaiton. International trade rules need to be revised to aim at achieving a fair trading system, in which the differential situations of countries at various stages of development are taken into greater consideration. Infant Industry argument evolved out of dissatisfaction with COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE which is concerned with STATIC EFFICIENCY and not conducive to LONG-TERM DEVELOPMENT = critics argue that current market prices and costs fail to serve as a guide to social needs and scarcities over time, because of the existence of dynamic externalities, uncertainties and risk. List says countries go through 5 stages in development Savage stage Pastoral stage Agricultural stage Agricultural and manufacturing stage Agricultural, manufacturing and commercial stage Transitions cannot be left to ‘natural course of things’ (market forces). Countries must industrialise in order to progress. Protection should be confined to the manufacturing sector, agriculture should not be protected. Main departure from SMITH is PHILOSOPHICAL. To List, ‘THE SUM OF INDIVIDUAL INTERESTS IS NOT NECESSARILY EQUAL TO THE NATIONAL INTEREST’ further, some nations may be more interested in their own welfare than the collective interests of humanity = in this instance, a nation might be more interested in the expansion of productive forces rather than maximising the welfare of humanity at large through free trade. Proposes theory of PRODUCTIVE POWER which goes beyond international trade – which emphasises that the productive power of a nation depends on ‘possession of natural advantage’ as well as STABILITY AND INSTITUTIONAL FACTORS AND INDEPENDENCE AND POWER AS NATIONS. Because of risks need INCENTIVES. And also INDUSTRIAL TRAINING OR EDUCATION OF THE COUNTRY AS A WHOLE. Need SUBSIDIES, REGULATION OF IMPORT DUTIES. TRADE IS ONLY AN INSTRUMENT OF DEVELOPMENT IT IS NOT AN END = the ultimate end is progress, development and independence. Aware of the limitations of the infant-industry application in small countries due to the size of their markets – but still thought that development of the manufacturing sector was important because of need for absorption of surplus labour in agriculture by that sector to prevent starvation of expanding population. LIST ARGUES THAT POLITICAL ECONOMY MUST REST UPON PHILOSOPHY, POLICY AND HISTORY FREE TRADE SHOULD BE LIBERALISED ONLY WHEN ALL NATIONS WILL HAVE REACHED THE SAME LEVEL OF DEVELOPMENT. 4. Hayek, F. 1945. ‘The Use of Knowledge in Society’. American Economic Review, Vol 35, No. 4 (September, 1945). Pages 519-530. Hayek argues against the establishment of a Central Pricing Board, as a centrally planned market could never match the efficiency of the open market because any individual knows only a small fraction of all which is known collectively. A decentralised economy thus complements the dispersed nature of information spread throughout society. ‘It is rather a problem of how to secure the best use of resources known to any of the members of society, for ends whose relative importance only these individuals know. Or, to put it briefly, it is a problem of the utilization of knowledge which is not given to anyone in its totality.’ (520) Di John on Hayek: Di John asserts that this article represents one of the best descriptions of what market forces do. It is a critique of NC methodology (understood as a methodology not an ideology i.e can actually be used to demonstrate that central planning as well as laissez-faire works) NC methodology assumes that people have full information about everything that is going on. (n.b. In economic theory, perfect competition describes markets such that no participants are large enough to have the market power to set the price of a homogeneous product. Because the conditions for perfect competition are strict, there are few if any perfectly competitive markets. Still, buyers and sellers in some auction-type markets, say for commodities or some financial assets, may approximate the concept. Perfect competition serves as a benchmark against which to measure real-life and imperfectly competitive markets.) Thus, in the perfect competition model, there is an invisible auctioneer who calls out prices before anyone makes any investment. In this respect the PC model actually has a central planner (auctioneer) and NC economics is misleading in suggesting otherwise. Idea that Social Science has to start with the fact that society is comprised of individual agents with LIMITED AND LOCAL KNOWLEDGE. We don’t know which investments are going to work out in the long-run – everything is a bet. Market creates valuable information in the form of prices ex-post(after everyone has made their bets prices provide information to decentralised agents with limited knowledge) it happens not before investment takes place but rather in the course of ‘RIVALRY.’(competition) The market provides: 1. INFORMATION about what is a valuable investment (after people make investment s some firms will succeed and others will not) 2. DISCIPLINE – those bets that are unviable will go bankrupt. Ex-post to process of investment. Hayek is examining the PROCESS OF ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT not its EQUILIBRIUMS. His work laid the foundation for institutional economics. ********* This article is quite dense – found a random (by no means reputable) site which you might want to look at (http://reality.gn.apc.org/econ/hayek.htm) outlines how Hayek is: 1. Against centralisation The point at issue between Hayek and the proponents of socialist economic planning is not ``whether planning is to be done or not''. Rather it is ``whether planning is to be done centrally, by one authority for the whole economic system, or is to be divided among many individuals'' (Hayek, 1945, pp. 520-21). The latter case is nothing other than market competition, which ``means decentralized planning by many separate persons'' (Hayek, 1945, p. 521). And the relative efficiency of the two alternatives hinges on whether we are more likely to succeed in putting at the disposal of a single central authority all the knowledge which ought to be used but which is initially dispersed ¼ or in conveying to individuals such additional knowledge as they need in order to fit their plans in with those of others. (ibid .) The next step in Hayek's argument involves distinguishing two different kinds of knowledge: scientific knowledge (understood as knowledge of general laws) versus ``unorganized knowledge'' or ``knowledge of the particular circumstances of time and place''. The former, he says, may be susceptible of centralization via a ``body of suitably chosen experts'' (Hayek, 1945, p. 521) but the latter is a different matter. [P]ractically every individual has some advantage over others in that he possesses unique information of which beneficial use might be made, but of which use can be made only if the decisions depending on it are left to him or are made with his active cooperation. (Hayek, 1945, pp. 521-22) Hayek is thinking here of ``knowledge of people, of local conditions, and special circumstances'' (Hayek, 1945, p. 522), e.g., of the fact that a certain machine is not fully employed, or of a skill that could be better utilized. He also cites the sort of specific, localised knowledge relied upon by shippers and arbitrageurs. He claims that this sort of knowledge is often seriously undervalued by those who consider general scientific knowledge as paradigmatic. 2. The importance of change Closely related, in Hayek's mind, to the undervaluation of knowledge of local and specific factors is underestimation of the role of change in the economy. One key difference between advocates and critics of planning concerns the significance and frequency of changes which will make substantial alterations of production plans necessary. Of course, if detailed economic plans could be laid down for fairly long periods in advance and then closely adhered to, so that no further economic decisions of importance would be required, the task of drawing up a comprehensive plan governing all economic activity would appear much less formidable. (Hayek, 1945, p. 523) Hayek ascribes to his opponents the idea that economically-relevant change is something that occurs at discrete intervals and on a fairly long time-scale, and that in between such changes the management of the productive system is a more or less mechanical task. As against this, he cites, for instance, the problem of keeping cost from rising in a competitive industry, which requires considerable day-to-day managerial energy, and he emphasises the fact that the same technical facilities may be operated at widely differing cost levels by different managements. Effective economical management requires that ``new dispositions [be] made every day in the light of circumstances not known the day before'' (Hayek, 1945, p. 524). He therefore concludes that central planning based on [aggregated] statistical information by its nature cannot take direct account of these circumstances of time and place, and ¼ the central planner will have to find some way or other in which the decisions depending upon them can be left to the man on the spot. (ibid .) Rapid adaptation to changing circumstances of time and place requires decentralisation-we can't wait for some central board to issue orders after integrating all knowledge. 3. Prices and information While insisting that very specific, localised knowledge is essential to economic decision making, Hayek clearly recognises that the ``man on the spot'' needs to know more than just his immediate circumstances before he can act effectively. Hence there arises the problem of ``communicating to him such further information as he needs to fit his decisions into the whole pattern of changes of the larger economic system'' (Hayek, 1945, p. 525) How much does he need to know? Fortuitously, only that which is conveyed by prices. Hayek constructs an example to illustrate his point: Assume that somewhere in the world a new opportunity for the use of some raw material, say tin, has arisen, or that one of the sources of supply of tin has been eliminated. It does not matter for our purpose and it is very significant that it does not matter which of these two causes has made tin more scarce. All that the users of tin need to know is that some of the tin they used to consume is now more profitably employed elsewhere, and that in consequence they must economize tin. There is no need for the great majority of them even to know where the more urgent need has arisen, or in favor of what other uses they ought to husband the supply. (Hayek, 1945, p. 526) Despite the absence of any such overview, the effects of the disturbance in the tin market will ramify throughout the economy just the same. The whole acts as one market, not because any of its members survey the whole field, but because their limited individual fields of vision sufficiently overlap so that through many intermediaries the relevant information is communicated to all. (ibid .) Therefore the significant thing about the price system is ``the economy of knowledge with which it operates'' (Hayek, 1945, pp. 526-7). He drives his point home thus: It is more than a metaphor to describe the price system as a kind of machinery for registering change, or a system of telecommunications which enables individual producers to watch merely the movement of a few pointers, as an engineer might watch the hands of a few dials, in order to adjust their activities to changes of which they may never know more than is reflected in the price movements. (Hayek, 1945, p. 527) He admits that the adjustments produced via the price system are not perfect in the sense of general equilibrium theory, but they are nonetheless a ``marvel'' of economical coordination. (ibid .) 4. Evolved order The price system has not, of course, arisen as the product of human design, and moreover ``the people guided by it usually do not know why they are made to do what they do'' (ibid .). This observation leads Hayek to a very characteristic statement of his general case against central planning. [T]hose who clamour for ``conscious direction''-and who cannot believe that anything which has evolved without design (and even without our understanding it) should solve problems which we should not be able to solve consciously-should remember this: The problem is precisely how to extend the span of our utilization of resources beyond the span of the control of any one mind; and, therefore, how to provide inducements which will make individuals do the desirable things without anyone having to tell them what to do. (Hayek, 1945, p. 527) Hayek generalises this point by reference to other ``truly social phenomena'' such as language (also an undesigned system). Against the idea that consciously designed systems have some sort of inherent superiority over those that have merely evolved, he cites A. N. Whitehead to the effect that the progress of civilisation is measured by the extension of ``the number of important operations which we can perform without thinking about them'' (Hayek, 1945, p. 528). He continues: The price system is just one of those formations which man has learned to use¼ after he had stumbled upon it without understanding it. Through it not only a division of labor but also a coordinated utilization of resources based on an equally divided knowledge has become possible¼ [N]obody has yet succeeded in designing an alternative system in which certain features of the existing one can be preserved which are dear even to those who most violently assail it such as particularly the extent to which the individual can choose his pursuits and consequently freely use his own knowledge and skill. (ibid .)