2007-02-25 PAINT pre..

advertisement

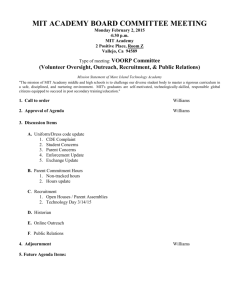

A System Dynamics (SD) Approach to Modeling and Understanding Terrorist Networks BAA-07-01-IFKA Proactive Intelligence (PAINT): Model Development Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) – – – Sloan School of Management Political Science Department Engineering Systems Division and National Security Innovations, Inc. (NSI) V11 2007-02-22 MIT 1 Agenda • Team • What is System Dynamics (SD) Modeling • Why is SD Modeling important • Challenge Problem to be addressed • Example of SD Modeling • Collaboration with other PAINT areas • Metrics & Validation • Management of Model Complexity – Key Sub-systems • Tasks, Deliverables & Timetable • Conclusion MIT 2 Key Personnel Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) – Stuart Madnick, Sloan School of Management, Information Technologies & School of Engineering, Engineering Systems Division – Nazli Choucri, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Political Science Department – Michael Siegel, Sloan School of Management, Information Technologies National Security Innovations, Inc. (NSI) – – Robert Popp, Founder and Chairman Greg Ingram, Vice President for Operational Technology All Key Personnel have considerable experience with the organization and management of large-scale projects that combine modeling and diverse data with application requirements in related areas – such as DARPA’s Pre-Conflict Analysis and Shaping (PCAS) effort 3 MIT Philosophy of System Dynamics • Every action has consequences • Often through complex non-linear feedback loops • Human are good at understanding individual pieces, • but difficult at comprehending the full impact Do you feel crowded in – and frustrated? MIT 4 See if you can get a bit more space by pushing on that wall … MIT 5 Oops … MIT 6 History of System Dynamics Modeling (SDM) SDM used as modeling & simulation method over 30 years • • Eliminate limitations of linear logics and over-simplicity Typical human assumptions and behaviors Better understanding system structure, behavior patterns, interconnections of positive & negative feedback loops, and intended & unintended consequences of action SDM has been applied to numerous domains, e.g., • • • • • Software development projects Process Improvement projects Crisis and threat in the world oil market Stability and instability of countries … many many others … SDM helps to uncover ‘hidden’ dynamics in system • • • MIT Helps understand ‘unfolding’ of situations Helps anticipate & predict new modes Explore range of unintended consequences 7 Appropriateness of Modeling Methodologies (adapted from Axelrod, 2004: “Modeling Security Issues of Central Asia”) Game Theory Agent-Based Modeling with Light Agents Agent Based Modeling with Heavy Agents Dynamical Systems System Dynamics Data-driven Models • • Construction time User Pre-requisites Learning Time Flexibility Repertory size Transparency L M L-H L L-H L M M H M L-H H H M M H L M M H H M M M L L L H L H M* M L M* M H Ideally, first three criteria should be Low, and the last three criteria should be High. The Criteria – – – – – MIT – Construction Time. Time and effort needed for a modeler skilled in this methodology to build a useful model with input from users. User Prerequisites. Amount of technical background needed by the user to understand as well as use the model. Learning Time. Time and effort for a typical user with the necessary prerequisites needs to learn a specific model. Flexibility. Ease with which the modeler can modify the model to incorporate a new variable. Repertory size. The number of published models of this type with features that could be adapted for use as part of a model on issues relevant to security in central Asia. Transparency. The ease with which the user can discover anything in the model that might bias the results. 8 Unique Capabilities of System Dynamics Modeling • • • • • • • • • MIT Objective input: Utilize data to determine parameters affecting the causality of individual cause-and-effect relationships. Subjective (expert) judgment: Represent and model cause-and-effect relationships, based on expert judgment. Intentions Analysis: Identify the long-term unintended consequences of policy choices or actions taken in the short term Tipping point analysis: Identify and analyze “tipping points” – where incremental changes lead to significant impacts. Transparency: Explain the reasoning behind predictions and outputs of the SD model. Modularity: Can organize SD models into collections of communicating sub-models (e.g., terrorism recruitment, economic development, religious intensity, regime stability) Scalability: Use the modularity to increase complexity without becoming unmanageable. Portability: Utilize the same basic SD model in different regions of the world without requiring re-formulation. Focusability: Increase details in specific areas of the SD model to address specific (and possibly new) issues. 9 PAINT Challenge Problem How should the Government analyze terrorist networks in the context of the political, religious, social and economic networks that intersect with, influence, and are influenced by, the terrorist network; predict the formation, evolution, vulnerabilities, and dissolution of the network; and identify strategies to shape or influence the network through selective action? MIT 10 Example of System Dynamics Modeling: Dissident and Terrorist Network Escalation (very simplified) Factors that affect rate of Flow Flows Avg Time as Dissident Stocks Appeasement Rate Population Births Dissidents Becoming Dissident Recruits Through Social Network MIT Appeasement Fraction Terrorist Recruitment Terrorists Desired Time to Remove Terrorists Removing Terrorists Removed Terrorists Regime Opponents 11 Dissident and Terrorist Network Development (slightly more detailed) Avg Time as Dissident Appeasement Rate Population Births Dissidents Insurgent Recruitment Becoming Dissident Recruits Through Social Network Regime Opponents Normal Propensity to be Recruited Propensity to be Recruited MIT Removing Terrorists Violent Incident Intensity Protest Intensity Removed Terrorists Propensity to Commit Violence Relative Strength of Violent Incidents Incident Intensity Effect of Incidents on Anti-Regime Messages Regime Resilience Social Capacity Political Regime Capacity Legitimacy Terrorists Propensity to Protest Effect of Regime Resilience on Recruitment Economic Performance Desired Time to Remove Terrorists Appeasement Fraction Effect of Anti-Regime Messages on Recruitment Perceived Intensity of Anti-Regime Messages Message Effect Strength Fifth-order system of non-linear differential equations: > 140 equations & > 100 feedback loops 12 Sample of Structure to Equations: Recruitment Section Population Becoming Dissident Pop Growth Fr Gr Rate Total Contacts Incitability Dissidents Terrorist Recruitment Terrorists Regime Recruits Through Opponents Social Network Cond Prob of Fract of Contacts Recruit with Regime Opponents Contacts Between Opponents and Population <Total Pop> Stocks Parameters Variables P = INTG(PG-BD)dt+Po D = INTG(TR-BD)dt+Do T = INTG(TR)dt+To FGR = 0.001706 I = 0.4 CPR = 0.1 RO = D+T TP = P+D+T FCWRO = RO/TP TC = P*I CBOP = TC*FCWRO RTSN = CBOP*CPR Flows MIT PG = P*FGR BD = RTSN 13 Example Intervention Policies: Removing Terrorists vs. Preventing Recruitment Increased Removal Effectiveness Avg Time as Dissident Appeasement Rate Population Births Dissidents Insurgent Recruitment Becoming Dissident Recruits Through Social Network Regime Opponents Normal Propensity to be Recruited Propensity to be Recruited Social Capacity MIT Political Regime Legitimacy Capacity Terrorists Removed Terrorists Removing Terrorists Propensity to Commit Violence Violent Incident Intensity Protest Intensity Relative Strength of Violent Incidents Incident Intensity Propensity to Protest Effect of Incidents on Anti-Regime Messages Effect of Regime Resilience on Recruitment Regime Resilience Desired Time to Remove Terrorists Appeasement Fraction Effect of Anti-Regime Messages on Recruitment Perceived Intensity of Anti-Regime Messages Message Effect Strength Preventing Recruitment 14 Example Intervention Policies: Removing Terrorists vs. Preventing Recruitment Terrorists 27,000 25,250 23,500 Better terrorist removal 21,750 20,000 2005 Preventing recruitment 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 Time (Year) MIT Better terrorist removal Preventing recruitment intelligence sharing moderate rhetoric Removing terrorists has a limited effect Preventing recruitment effects a sustained reduction 15 Collaboration with other PAINT areas: Architecture and Integration, Key Indicators, & Dynamic Gaming and Strategies • • • Worked with other potential PAINT researchers, such as in PCAS. Expertise that we can contribute to the overall PAINT effort. Architecture and Integration Innovative IT Architectures for Integration are major research foci for our MIT group at MIT. • • “Context Interchange: Using Knowledge about Data to Integrate Disparate Sources,” was projects under DARPA’s Intelligent Integration of Information (I3) research program - further improved and tested in various environments, including a recent project to facilitate the integration of intelligence data. Key Indicators Key Indicators are important part of our proposed work on the PAINT effort. We have experience with identifying and understanding Key indicators in other projects. Dynamic Gaming and Strategies System Dynamics extensively used by MIT in dynamic gaming, called “management flight simulators” to demonstrate how managerial “instincts” often lead to counter-intuitive and erroneous results. MIT 16 ‘What if’ “Virtual / Gaming mode” - Parameter Inputs with Sliders MIT 17 • Metrics & Validation Many ways to validate a System Dynamics model – – • Behavioral Reproduction – – – – • MIT 12 ways on p. 6 of proposal we will use all of them; two are below: Use past data (as well as other sources) to help determine parameters up to, say, two years ago. Each “stock” (e.g., number of terrorists) is a metric. Measure how well SD model projections match the following years planned changes, known 2 years ago, to policy are included. In PCAS effort, our SD model predictions were very accurate. System Improvement – Does the model generate useful insights that are appreciated by decision makers? – In PCAS effort, our results were presented to PACOM, etc. 18 Managing Model Complexity • • “A model should be as simple as possible and only as complex as needed.” Unneeded complexity will be avoided in this project. The primary method to manage SD model complexity is the use of subsystems (which can be further decomposed into sub-subsystems, if needed.) – • (a) regime resilience (b) terrorist network activities and growth. (c) government capacity & interactions with terrorist networks Each of these subsystems have internal dynamics as well as dynamic interactions with the other subsystems. – – MIT Our current plan is divide our High Level Model (HLM) into at least three major subsystems: Multi-level layer approach simplifies the complexity both in model development and refinements as well as model usage and understanding. Used very effectively in many SD modeling projects. 19 Proposed Tasks & Timetable (timetable on p. 16, details of 36 tasks on pp. 23-26 of proposal) Working Integrated SD model delivered each year and improved each year. Phase 1 (18 months) – Component Predictive Models Integrated into a Virtual World/Dynamic Gaming Collaborative Key task is to design, develop, and complete the High Level Model (HLM) including all subsystems: (a) regime resilience, (b) terrorist network activities and growth, and (c) government capacity and interactions with terrorists. Basic data for the HLM compiled to provide an empirical view of the overall model. Phase 2 (12 months) – Prediction Using Specific Challenge Problem with Historical or Synthetic Data All subsystems enhanced; focus on improving the regime resilience sub-system. Phase 3 (12 months) – Prediction using Real World Data Instrumentation, Feedback and Fine tuning All subsystems enhanced; focus on the terrorist network activities and growth sub-system Phase 4 (12 months) – Grand Challenge Problem: Influence Strategies for Alternative Futures All subsystems enhanced; focus on the government capacity sub-system and interactions with terrorists; development and analysis of strategies leading to better improved alternative futures. MIT 20 Conclusions • System Dynamics methodology important • • • • MIT and critical method for addressing the broad scope of PAINT. SD has been shown effective is related efforts (e.g., PCAS). We have assembled superb multidisciplinary team We are committed to the success of PAINT. Thank you. 21 Backup Slides – For Q&A MIT 22 Quick Primer: What (and Why) of System Dynamics Consider the domain of Software Development 1. “Knee jerk” reaction to a project behind schedule is to add people. 2. “Brooks Law” noted that “Adding people to a late project, just makes it later” • Because the new people must be trained, this takes productive people off the project – which was not obvious before. • These points are now fairly well-known by most software developers – but still naïve. • • Many other factors: length of project, type of project, expertise of staff available, approach to and time needed to do training, stage of project, etc. Over the years, all of these individual factors have been well-studied individually – but how do they interact ? • System dynamics helps model & study the dynamics of the interdependencies. Non-obvious outcomes frequently found. (e.g., sometimes Brooks is wrong! When and Why?) Source: Software Project Dynamics: An Integrated Approach, by T.K. Abdel-Hamid and S. Madnick, Prentice-Hall, 1991, and Fred Brooks, The Mythical Man-Month, 1975. MIT 23 Validation of System Dynamics Models • • • • • • • • • • • • MIT Boundary Adequacy: Does the selection of what is endogenous, exogenous, and excluded make sense? Structure Assessment: Is the level of aggregation correct, and does the structure conform to reality? Dimensional Consistency: Do the units of the model make sense, and does the model avoid the use of arbitrary scaling factors? Parameter Assessment: Do the parameters have real life meanings, and are their values properly estimated? Extreme Conditions: Do extreme parameter values lead to irrational behavior? Integration Error: Does the behavior change when the integration method or time step are changed? Behavioral Reproduction: How well does the model behavior match the historical behavior of the real system? Behavior Anomaly: Does changing the loop structure lead to anomalous behavior consistent with the changes? Family Member: How well does the model “scale” to other members within the same class of systems? Surprise Behavior: What is revealed when model behavior does not match expectations? Sensitivity Analysis: Do conclusions change in important ways when assumptions are varied over their plausible range? Changes in conclusions could be numerical changes, behavior mode changes, or policy changes. System Improvement: Does the model generate insights that actually lead to the hoped for improvements? 24 ‘What if’ “Virtual / Gaming mode” - Parameter Inputs with Sliders MIT 25 Example End-User (Non-Technical) Interface Design MIT 26 Resumes of Key Personnel - MIT Dr. Stuart Madnick is the John Norris Maguire Professor of Information Technology, Sloan School of Management and Professor of Engineering Systems, School of Engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He has been a faculty member at MIT since 1972. He has served as the head of MIT's Information Technologies Group for more than twenty years. He has also been a member of MIT's Laboratory for Computer Science, International Financial Services Research Center, and Center for Information Systems Research. Dr. Madnick is the author or co-author of over 250 books, articles, or reports including the classic textbook, Operating Systems, and the book, The Dynamics of Software Development, which received the Jay Wright Forrester Award for "Best Contribution to the field of System Dynamics in the preceding five years" awarded by the System Dynamics Society. His current research interests include connectivity among disparate distributed information systems, database technology, software project management, and the strategic use of information technology. He is presently co-Director of the PROductivity From Information Technology Initiative and co-Heads the Total Data Quality Management research program. He has been active in industry, as a key designer and developer of projects such as IBM's VM/370 operating system and Lockheed's DIALOG information retrieval system. He has served as a consultant to corporations, such as IBM, AT&T, and Citicorp. He has also been the founder or co-founder of high-tech firms, including Intercomp, Mitrol, and Cambridge Institute for Information Systems, iAggregate.com and currently operates a hotel in the 14th century Langley Castle in England. Dr. Madnick has degrees in Electrical Engineering (B.S. and M.S.), Management (M.S.), and Computer Science (Ph.D.) from MIT. He has been a Visiting Professor at Harvard University, Nanyang Technological University (Singapore), University of Newcastle (England), Technion (Israel), and Victoria University (New Zealand). MIT 27 Resumes of Key Personnel (continued) - MIT Dr. Nazli Choucri is Professor of Political Science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Director of the Global System for Sustainable Development (GSSD), a distributed multilingual knowledge networking system to facilitate uses of knowledge for the management of dynamic strategic challenges. To date, GSSD is mirrored (i.e. synchronized and replicated) in China, Europe, and the Middle East in Chinese, Arabic, French and English. As a member of the MIT faculty for over thirty years, Professor Choucri’s area of expertise is on modalities of conflict and violence in international relations. She served as General Editor of the International Political Science Review and is the founding Editor of the MIT Press Series on Global Environmental Accord. The author of nine books and over 120 articles Professor Choucri’s core research is on conflict and collaboration in international relations. Her present research focus is on ‘connectivity for sustainability’, including e-learning, e-commerce, and edevelopment strategies. Dr. Choucri is Associate Director of MIT’s Technology and Development Program, and Head of the Middle East Program. She has been involved in research, consulting, or advisory work for national and international agencies, and in many countries, including: Abu Dhabi, Algeria, Canada, Colombia, Egypt, France, Germany, Greece, Honduras, Japan, Kuwait, Mexico, North Yemen, Pakistan, Qatar, Sudan, Switzerland, Syria, Tunisia, Turkey Dr. Michael Siegel is a Principal Research Scientist at the MIT Sloan School of Management. He is currently the Director of the Financial Services Special Interest Group at the MIT Center For eBusiness. Dr. Siegel’s research interests include the use of information technology in financial risk management and global financial systems, eBusiness and financial services, global ebusiness opportunities, financial account aggregation, ROI analysis for online financial applications, heterogeneous database systems, managing data semantics, query optimization, intelligent database systems, and learning in database systems. He has taught a range of courses including Database Systems and Information Technology for Financial Services. He currently leads a research team looking at issues in strategy, technology and application for eBusiness in Financial Services. MIT 28 Resumes of Key Personnel (continued) – NSI Dr. Robert Popp is cofounder of National Security Innovations (NSI), Inc., presently serving as its Chairman and CEO. Prior to NSI, Dr. Popp served as Executive Vice President of Aptima, Inc. Prior to Aptima, Dr. Popp served for five years as a senior government executive within the Defense Department: one year at the Office of the Secretary of Defense as Assistant Deputy Undersecretary of Defense for Advanced Systems and Concepts, and four years at the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). At DARPA, Dr. Popp served as Deputy of the Information Awareness Office (IAO) where he oversaw a portfolio of over 25 programs exceeding $170M focused on novel IT-based tools for counter-terrorism, foreign intelligence and national security. Dr. Popp was also Deputy PM to Dr. Poindexter on the Total Information Awareness (TIA) program, a program that integrated and experimented with analytical tools in text processing, collaboration, decision support, foreign languages, predictive modeling, pattern analysis, and privacy. Dr. Popp also served as Deputy of the Information Exploitation Office (IXO), where he established a novel research thrust in stability operations and quantitative/computational social science modeling for nation state instability and conflict analysis. Prior to government service, Dr. Popp held senior positions with ALPHATECH, Inc. (now BAE Systems) and BBN. He has served on the Defense Science Board (DSB), is a Senior Associate for the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), and is a founding Fellow of the Academy of Distinguished Engineers at the University of Connecticut. Dr. Popp also served in the military from 1982 – 1988 as a Staff Sergeant in the US Air Force as an Aircraft Maintenance Technician of F106 fighters and B52 bombers. Dr. Popp holds a Ph.D in Electrical Engineering from the University of Connecticut, and a BA/MA in Computer Science (summa cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa) from Boston University. Gregory J. Ingram is the Vice President for Operational Technology for National Security Innovations MIT (NSI), Inc. He has twenty-four years of experience in the Army in the fields of Special Forces, Infantry, Civil Affairs, and Psychological Operations (PSYOP). Fifteen of his twenty-four years have been on active duty and the remainder in the reserves. He has deployed in various capacities to Lebanon, Italy, Chile, Korea, Haiti, Afghanistan, and Iraq. For the last five years, Greg has been heavily involved in developing, integrating, and operationalizing leading-edge technologies in the areas of knowledge discovery, planning and analysis, human language technologies, and quantitative social science methodologies. Greg served as the lead PSYOP/IO Planner in the Special Operations Joint Interagency Collaboration Center (SOJICC) and as an Operational Manager for the development of the PSYOP Planning and Analysis System (POPAS) as part of the PSYOP Global Reach (PGR) Advanced Concept Technology Demonstration (ACTD) at the United 29 States Special Operations Command (USSOCOM).