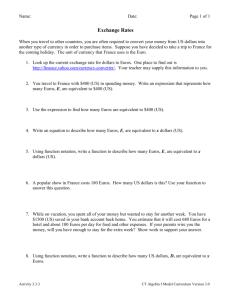

Cost

advertisement

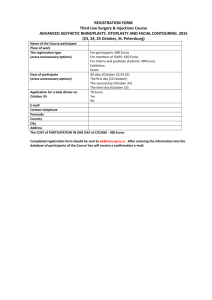

NATIONAL AND KAPODISTRIAN UNIVERSITY OF ATHENS Faculty of Economics Department of Business Economics and Finance Center of Financial Studies Laboratory for Investment Applications Internal Audit Program Course: Managerial Economics and Financial Management - Chapter 3 Instructor: Panayotis Alexakis In cooperation with: Under the aegis of: Managerial Economics and Financial Management Chapter 3: Cost Concepts for Decision Making Contents of presentation: The economic cost as an opportunity cost Forms of costs and management rules Cost and the choice of the size of the production unit Breakeven analysis and operational leverage Economies of scale, learning and combining Introduction Every business decision takes place following the comparison between the benefits, that is the revenues to be obtained, and the costs related to it. Benefits should exceed costs. The measurement of cost related to a business decision must be accurate, which is not an easy case for two main reasons: 1. The economic cost for the production of a good may differ from the expenditures occurred for the production of this good. 2. The use of fixed assets do not become obsolete after the production of a certain quantity of the good, but instead remain and are used for the production of more product units in the course of time. 3 The economic cost as an opportunity cost As microeconomic theory indicates, the correct measurement of cost is the one that takes place under the concept of the opportunity cost. The opportunity cost of a production factor is determined by its value in its best possible use. The prices prevailing in the market for a production factor are considered as a satisfactory indicator of the opportunity cost. This is justified by the understanding that market prices express the amounts that the various users of this factor are willing to pay for the acquisition of this production factor. 4 The economic cost as an opportunity cost Example: Let us suppose that a raw material, say aluminum, is used for the production of goods by various factories. The prevailing market price represents the value that the marginal user places for its use. The acquisition of a unit of raw material by another user deprives this unit from the marginal buyer and prevents him to produce a value that is equal to the raw material value that he is willing to pay. 5 The economic cost as an opportunity cost An alternative way to comprehend OC: Let us suppose that a firm possesses a quantity of raw material in its warehouse. In order for the company to estimate correctly whether the use of the raw material is to its benefit, the company could consider the price prevailing in the market. This price is the opportunity cost because the alternative use for the company would be to dispose it to the market and obtain revenues at the market price. 6 The economic cost as an opportunity cost The previous example of the warehouse raw material is sufficient in order to shed light on the important difference between accounting and economic cost. Differences: The accounting cost has to do with the recording of the expenditures that were realised for the production of a unit of a product. The economic cost represents the opportunity cost. The accounting cost implements the reporting of expenditures that were undertaken. The economic cost takes into account the alternative uses of resources and forms the appropriate calculation for proper management decisions. Under certain conditions, both coincide while under other conditions they differ. 7 The economic cost as an opportunity cost Example: Suppose that company A undertakes the production of aluminum frames and has for this reason acquired and keeps in its warehouse 10 tons of aluminum, at the price of € 1,000.00 per ton. Three months later, it is getting prepared to use this quantity to the production of aluminum frames. However, within these three months international aluminum demand has suddenly increased due to needs of the aerospace industry, resulting a rise in the price to € 1,100.00 per ton 8 The economic cost as an opportunity cost If A has the ability to sell this raw material stock to the market at the price of € 1,100.00 per ton, this new price is the opportunity cost of the use of aluminum for the production of frames. The initially purchased price € 1,000.00 per ton, has however been recorded in the company books and presents the accounting cost. If the aluminum price remains steady during the quarter between the purchase and the use of the raw material, then both the accounting and the economic cost would coincide. If, however, the price had been reduced in the meantime, then the economic cost would be lower as compared to the accounting cost. 9 The economic cost as an opportunity cost However: The prices prevailing in the market are not sufficient for all cases for the determination of the opportunity cost. This happens, mainly, for the cases that certain production factors are so specialized in the production of a company that their alternative uses outside the company are rare or absent. The cases where this happens relate mainly to machinery. The source of this problem can be understood, as contrary to the raw material which is offered for many uses, specialized machinery has a very different acquisition price and sale price, subsequently. Usually, the second price is lower than the first. For this reason, the opportunity cost of a machinery, before its use by the company, equals the market price, while following its acquisition, equals the sale price. 10 The economic cost as an opportunity cost A last dimension of the opportunity cost of particular importance for the case of equipment, has to do with its multiple use inside a company. Example: A machine can be used for the production of product I and also of product G. Its use for product I, represents an opportunity cost equal to the income that would be achieved from its alternative use for the production of G. It becomes evident that, in this case, an intracompany comparison of alternative uses is taking place, which depends not on the value of the machine but on the profitability it generates to the various activities of the company. 11 Forms of costs and management rules The identification of the cost connected to each entrepreneurial decision is assisted if one takes into account the various forms of cost appearing in practice. One first dimension assisting towards this direction is the distinction between explicit and implicit cost. Explicit cost is easily calculated as it is composed of expenditures directly related with the activity. The calculation of implicit cost is more troublesome as it has to be perceived as an opportunity cost. 12 Forms of costs and management rules Example: Let us suppose a unit producing pairs of stockings, and requires the purchase of fixed assets of 100,000 euros, annual labour cost (in full capacity) of 15,000 euros, and cost of raw materials and energy of 10,000 euros. The last two categories of costs are to be covered by the sales. The cost of fixed assets should be covered immediately. Two businessmen, A and B, separately, consider the undertaking of this activity. A already possesses 100,000 euros through savings. B must borrow at 15% borrowing rate and therefore has to bear an additional annual amount of 15,000 euros. 13 Forms of costs and management rules It can be seen that the explicit cost is higher for B (15,000 + 10,000 + 15,000 = 40,000 euros) as compared to A (15,000 + 10,000 = 25,000 euros). However, it would be a mistake to conclude that the production of stockings is more profitable for A, as he is subject to the implicit cost of 15,000 euros. This means that the 100,000 euros that he possesses imply an opportunity cost, as he could lend this amount at an interest of 15%, instead of using it for the purchase of the fixed assets. Therefore, the total annual cost is the same for both A and B. 14 Forms of costs and management rules A second distinction is the one between incremental and disbursed cost. The incremental cost of a business decision equals the total outflow that is exclusively related to this decision. On the contrary, the disbursed cost is composed of outflows that have already taken place which do not change due to the undertaking of the business activity under study. 15 Forms of costs and management rules Example: Company ABC spends 50,000 euros for the construction of a warehouse with freeze compartments, especially designed for the maintenance of dairy products. Unfortunately, the processing of dairy products that was planned was cancelled due to environmental problems threatening milk contamination. Since that time the warehouse remained unutilized and the freeze compartments were subjected to destruction. Now ABC plans to use the warehouse and its equipment for meat maintenance. The repairs and adjustments that have to be undertaken require expenses of 23,000 euros, while the new activity is estimated to bring revenues (before the warehouse costs) of 32,000 euros. 16 Forms of costs and management rules The question is whether this activity should be undertaken. The incremental cost of this activity is to generate a profit of 9,000 euros and therefore it is beneficial and is recommended for realization. The initial warehouse and equipment cost should not be taken into account as it is an already disbursed amount and this expenditure exists, independently of whether the new activity is undertaken or not. 17 Forms of costs and management rules The third cost dimension, is already known from economic theory and distinguishes between fixed and variable cost. While in the previous two cases, the analysis is related to a business activity in total, this last distinction refers to the way that the production cost changes as the quantity produced changes, too. The fixed cost is the size which does not depend on the change of the production quantity 18 Forms of costs and management rules Fixed cost is related to fixed expenses (buildings, equipment, installations, managerial operation), which are required for the fulfillment of the production activity and remain steady irrespective of the production scale (of course, within limits). Example: The expenses for space rental, the interest paid on company loans for the acquisition of equipment, the salaries of top executives, refer to sizes which do not depend on the upward or downward changes of the production level. 19 Forms of costs and management rules The variable cost depends on the number of units produced. It originates from expenses on production factors which are incorporated in each production unit (e.g. a raw materials, energy, labour cost). These expenses, obviously, depend on the production cost. 20 Forms of costs and management rules Having in mind the characteristics which, respectively, determine the fixed and the variable cost, it can be easily deducted that their relative sizes depend on the production function that is used. A production procedure that is highly capital intensive brings forth a high fixed cost, while a production procedure of low capital intensity is related to a relatively higher variable cost. 21 Forms of costs and management rules Cost sizes Quantity Total Fixed Variable Average Average Average Marginal Cost Cost Cost Total Fixed Variable Cost (TC) (FC) (VC) Cost Cost Cost (ATC) (AFC) (AVC) (MC) 1 120 100 20 120.0 100.0 20.0 20 2 138 100 38 69.0 50.0 19.0 18 3 151 100 51 50.3 33.3 17.0 13 4 162 100 62 40.5 25.0 15.5 11 5 175 100 75 35.0 20.0 15.0 13 6 190 100 90 31.7 16.7 15.0 15 7 210 100 110 30.0 14.3 15.7 20 8 234 100 134 29.3 12.5 16.8 24 9 263 100 163 29.2 11.1 18.1 29 10 300 100 200 30.0 10.0 20.0 37 22 Forms of costs and management rules Costs per product unit 23 Forms of costs and management rules The table and diagram above incorporate three worth observable points: a) The effect of the fixed cost in the formation of the cost per unit of output is continuously falling. Therefore, on the side of fixed cost, it is to the benefit of the company to achieve the maximum possible increase of production. b) The effect of the variable cost in the formation of the cost per unit of output is initially falling. However, after the 6 units produced it becomes rising. For this reason, the maximum possible increase in production may not necessarily be the most beneficial from the side of total cost. In the above examples, the minimum total cost per unit of output is achieved at 9 units produced. c) The marginal production cost does not coincide with the average cost, as it presents the change in total cost. This change is due to the variable cost change as production increases by one unit, given that fixed cost remains unchanged. 24 Forms of costs and management rules Note: The distinction between fixed and variable cost requires special attention on the part of decision making, as it is valid only within certain limits. The production factors which determine fixed cost have always a maximum use limit and they can support the production process up to a given scale. For example, the capacity utilization of a factory, the capacity of a warehouse, the capacity of a management team to offer services, they all have a natural limit. Within this limit, the distinction between fixed and variable cost is valid. Beyond this limit, it is not valid as the increase of production at a higher scale requires the additional capacity of the factory, new warehouse spaces, or more executives. 25 Forms of costs and management rules Using the example of the above table, suppose also that the production limit is at 10 product units. The 11th unit requires new installation leading to the change of fixed cost from 100 to 200. The same can be repeated for the 21st unit and so on. Therefore, in order for production to be increased to a bigger scale, the fixed cost is transformed to variable, too. However, since the big changes in the production scale occur usually (not always) in long time periods, economics considers the presentation of the above table as representing the short term behavior of cost, while it considers that when adopting a long term perspective all cost kinds are variable. 26 Forms of costs and management rules From the company side, the decision makers must consider as short term the least period required for the change of the production factors which affect (feed in) the fixed cost. For example, if the change in the production capacity of a factory requires construction works for a year, the short term behavior of cost applies for a period less than a year. 27 Inventory management as cost factor Managing the company’s supply chain and logistics, the sources of its raw materials and inputs and the handlers of the outcome (outputs), forms one of the essential direct cost factors which contribute to pricing. A company carries inventories because of the difficulty to predict, quantities and also the timing and location of demand (or supply). Minimizing cost (so minimize one of the pricing factors), is essential in this case by finding the optimal inventory level. 28 Inventory management as cost factor The most significant factors are: a. Ordering costs which are fixed costs of placing an order - independent of the amount of units ordered, and b. Carrying costs (known as holding costs), which may be, rents, taxes, lying and demurrage charges, depreciation (or obsolesce), and opportunity cost, among others. Carrying costs are reduced by minimizing the inventory level. Also other non-operating factors, such as theft, or waste can play their role. In order to avoid troubles and risk stock-outs and shrinkages, safety stock must always be present. 29 Theoretical model The challenge is to find the spot where total costs of inventory are minimum (given the total cost and the order quantity). The intersection of the carrying costs with the ordering costs curve is represented by the following formula. EOQ=[(2ad/K)] 1/2, which a= variable cost per order (or production setup) d= Demand (periodical) in units K= Carrying cost (unit periodic) 30 Theoretical model 31 Theoretical model This formula indicates that EOQ varies directly with demand and order (setup) costs, and varies inversely with carrying costs. The average level of inventory is always the ½ of the EOQ. The model has its limitations relating to its restrictive assumptions on these 3 variables, which remain constant throughout the period. Also, stock-out costs here are zero and no safety stock is held. 32 Practical models (methods) ABC Inventory Management ABC method focuses on cost-reducing tactics and leads managerial control by often and regularly reviewing the inventory on A Group, less often in B Group and not so often on C Group (because it consists, from lesser value inventory items). 33 Cost and the choice of the size of the production unit So, the size of a production unit, a factory for example, determines the limits and the relative magnitudes of fixed and variable cost. Under a different size of a factory the short term cost curves will differ, too. The following diagram presents three cases of factory scales A, B, C, where A is the smallest and C is the largest scale. 34 Cost and the choice of the size of the production unit Q1 Q* Q2 35 Cost and the choice of the size of the production unit Size of Production Unit and Variations in Production and Sales 36 Cost and the choice of the size of the production unit As it can be seen from the diagram, the lower cost per unit of output is achieved when the production scale B is selected, with Q* being the quantity produced. This, however, does not imply that the company will, at all cases, select this production scale. If it expects that production will exceed Q2, then production scale C forms the best choice. Production scale B is more appropriate for production levels which are between Q1 and Q2. 37 Cost and the choice of the size of the production unit Another, but equally essential, dimension in the choice of the size of a production unit refers to the flexibility in large variations of the quantity of production. Diagram (a) depicts a typical presentation of this characteristic. It can be observed that the production unit A achieves a very low cost per unit of output at the level of 5,000 units, while unit B depicts a higher cost, at the same level. Unit A depicts a very large cost increase as production moves away from the level of 5,000 units. 38 Cost and the choice of the size of the production unit On the contrary, unit B presents a small cost increase only for production levels above 5,000 units. From the cost side, unit A is a specialised factory achieving very high return, for a specific production scale, while unit B is very flexible to changes in production. Furthermore, selecting the type of unit A is not the best business decision, always. The right choice depends on the degree of variation of production and this in turn is determined by the variation in sales. 39 Cost and the choice of the size of the production unit Diagram (b) on production size and variations in production and sales, presents two probability distributions of sales. Both present an expected sales level of 5,000 units. However D depicts a relatively smaller variation around the expected level of 5,000 production units, while E has a significant variation. If the probability distribution D presents the sales behavior correctly, then the choice of type A production unit is favoured. If on the other hand distribution E presents the right sales behavior, then production unit B is favoured. 40 Break even analysis and operational leverage The formation of the production cost leads to the right business decision only if it is combined with the revenues from the sales of the product. One known way for the analysis of this combination is the break even analysis. The break even point of a company refers to the quantity of production where revenues are exactly offset by the production cost, and it is estimated with the use of the production cost. 41 Break even analysis and operational leverage The break even point is calculated as follows: Suppose that: P, is the price per unit of product Q, is the quantity of the product, produced and sold FC, is the fixed cost AVC, is the variable cost per unit of product QB, is the break even quantity produced and sold. The break even point requires that revenues equal costs: (1) PxQB FC (QB xAVC) 42 Break even analysis and operational leverage which derives: FC QB P AVC (2) Example: Suppose that a publishing company V plans the publication of a book on the medical science. The cost of publication is as follows: 43 Break even analysis and operational leverage Fixed cost € Correction texts 1,700 Pictures 2,700 Composition 5,600 Total fixed cost Variable cost per book Paper, printing, binding Bookshop fee Writer rights General Sales Expenses Total variable cost p.b. Sale price per book 10,000 € 1.21 0.80 0.34 0.85 3.20 4.00 44 Break even analysis and operational leverage Then by formula (2) above: 10,000 QB 12,500books 4 3.2 It is derived that for the company to produce profits, it has to sell more than 12.500 books. If the estimations from the market suggest that a lower number of books will be absorbed, then this publication does not have profit prospects. 45 Break even analysis and operational leverage However, before the publication is abandoned, two other solutions could be analysed. One solution is to raise price to € 4.50 per book, as in this case the break even point is at 7,962 books. The other solution lies on cost cutting. If by using a simpler set of pictures reducing fixed cost by 1,000 units, a different quality of paper and simplifications on binding reducing average variable cost by 0.5 euros per book, then the break even point is at 6,923 books sold. Certainly, the company could combine the reduction in cost with the rise in the price per book 46 Break even analysis and operational leverage However, it should be stressed that there are limits on these maneuvers. The rise in price is not always possible, when competitors offer lower prices, while cost reduction reduces the quality of the product leading to a lower sales price. Finally, the increase in price could lead certain cost elements upwards, such as writer rights, bookshop fees, which are estimated as a percentage of sales. 47 Break even analysis and operational leverage An alternative presentation of the break even analysis refers to the calculation of the quantity of production and sales which leads to the minimum profit. Many companies consider that an activity should be undertaken only if it brings forth a minimum level of profit. By defining MI as the minimum profit and QMI the quantity that secures this minimum profit, then: (3) PxQMI FC QMI xAVC MI 48 Break even analysis and operational leverage And, QMI FC MI P AVC (4) By comparing (4) and (2), it can be seen that always: QMI QB , When QMI is positive By using the example of the publishing company, let us assume that the publication is to proceed only if it brings forth a minimum profit of 1.000 euros. Then, 49 Break even analysis and operational leverage QMI 10,000 1,000 13,750books 4 3.2 So, while a publication of 12,500 books realised zero profit, when 13,750 books are produced and sold, a profit of 1,000 euros is secured. Based on formula (4), one can search various choices relating to cost and price adjustments. 50 Break even analysis and operational leverage Break even analysis or analysis of the minimum profit quantity, provides information on the minimum production levels without losses or with a minimum profit. Frequently, in reality the production and sales size is not steady but varies according to the market situation, the evolution of incomes and seasonal factors, among others. For this reason, a sensitivity measure is needed on the level of profits to the variation of sales. This measurement is achieved with the use of the Degree of Operational Leverage (DOL). 51 Break even analysis and operational leverage It practically measures the elasticity of profits with respect to the product quantity: dI Q DOL x dQ I (5) when dI is the marginal change of profit and dQ is the marginal change of the quantity. 52 Break even analysis and operational leverage From the above, profit is defined as follows: I=(PxQ)-(AVCxQ)-FC (6) The size dI / dQ is the derivative of profit with respect to quantity: (7) dI P AVC dQ while, I / Q is derived from (6) as follows: (8) I FC P AVC Q Q 53 Break even analysis and operational leverage DOL is produced when dividing (7) with (8): Qx ( P AVC )(10) DOL Qx ( P AVC ) FC Formula (9) can be understood in a simple way, given that the nominator and the denominator differ only due to the deduction of FC in the denominator. By defining (P - AVC) as the operational profit margin per unit of output, then DOL can be determined by the relative sizes of the operational profit and the fixed cost. The bigger the operational profit in relation to fixed cost the smaller the DOL, and the reverse. 54 Break even analysis and operational leverage That is, when the company has a relatively large operational profit and a smaller fixed cost, (labour intensive company), the sensitivity of profit on the variation of sales is being reduced. Example: Let us suppose two companies A and B produce exactly the same product but with a different technology. The sales price per product unit is 20 euros. A uses simple equipment but a large quantity of labour, while B (capital intensive) uses a complicated equipment of high automaticity and very small labour quantity. The formation of cost appears in the following table. 55 Break even analysis and operational leverage Cost formation, revenues and breakeven point Company A Company B FC 200,000 600,000 AVC 15 10 P 20 20 56 Break even analysis and operational leverage Quantity Revenues Cost Profit Revenues Cost Profit (000 (000 (000 (000 (000 (000 euros) euros) euros) euros) euros) euros) 20,000 400 500 -100 400 800 -400 40,000 800 800 0 800 1000 -200 60,000 1200 1100 100 1200 1200 0 80,000 1600 1400 200 1600 1400 200 100,000 2000 1700 300 2000 1600 400 120,000 2400 2000 400 2400 1800 600 140,000 2800 2300 500 2800 2000 800 160,000 3200 2600 600 3200 2200 1000 57 Break even analysis and operational leverage From the sizes of this table it can be seen that: Firstly, A has a lower break even point than B (40,000 and 60,000, respectively). Therefore, by increasing production, it achieves profits at an earlier stage, than B. Secondly, by increasing production beyond the breakeven point, B achieves a much faster increase of profits, than A. Thirdly, the profits of B appear to have a higher sensitivity to the variation of production. This is also derived from the calculation of DOL for the two enterprises in various production levels. 58 Break even analysis and operational leverage For example: At the level of production of 80,000 units: 80,000 x(20 15) DOL ( A) 2 80,000 x(20 15) 200,000 120,000 x(20 15) DOL ( B) 4 120,000 x(20 15) 600,000 59 Break even analysis and operational leverage At the level of production of 120,000 units: 120,000 x(20 15) DOL ( A) 1.5 120,000 x(20 15) 200,000 120,000 x(20 15) DOL ( B) 2 120,000 x(20 15) 600,000 Note: DOL is always bigger for company B. 60 Break even analysis and operational leverage A «critique» of DOL 1. 2. The use of DOL and the break even analysis is certainly very informative for business decision making. However, there seem to be two restrictions that should be taken into account in the analysis: It assumes that the sales price is constant and independent from the production and sale levels. If the sale price varies, then a demand function has to be incorporated to the analysis which links the change in prices with the change in quantity. It assumes an average variable cost which is also given and independent from the production level. This assumption too can diverge from reality. In this case one has to incorporate an estimation of the cost function to the analysis. 61 Economies of Scale, Learning and Combining The purpose? When it comes to business initiatives of long term prospects and growth of the production activity, the cost estimation must be undertaken on the basis of projections of its size, when the company is at a future advanced stage of development, as compared to the present. Along the growth of a company and production, three frequent phenomena are taking place which are conducive to the reduction of cost. These are the economies of scale, the economies of learning and the economies of combining. Certainly, all three have to be estimated for each particular case so that their presence is verified, as well as the size of their effect. 62 Economies of Scale, Learning and Combining 1. Economies of scale The economies of scale describe the case where for long periods of production increases, the reaction of the quantity produced is that it increases at a rate which is bigger than the proportional rise of the production factors used towards this purpose. For example the doubling of the production scale requires less than double increase of production factors, which implies that as production increases the average cost per unit of product is being reduced. Therefore, economies of scale are achieved as the cost per additional product unit is being reduced during the increase of production, which is explained by reasons of operational efficiency in the production process. 63 Economies of Scale, Learning and Combining Why is that happen? Due both to the fact that the fixed cost is being absorbed by the rising volume of production, as well as to the fact that the bigger production, the standardization of the product and the labour specialization are combined for the production and contribute to the reduction of the variable cost. More specifically, the existence of economies of scale, is related to certain significant determinants. So, indivisibilities on the use of certain production factors, in combination to the abilities of large production units, frequently drive the production increase at faster rates as compared to the rate of increase of production factors. 64 Economies of Scale, Learning and Combining Bigger production units entail a more efficient utilization and specialization of the labour force and therefore its effectiveness, as well as a higher effectiveness of the total production process. Also, technology acts as a catalyst to the achievement of this phenomenon, as it frequently leads to the complete utilization of large scale equipment and / or to improvement of the quality of the final product. The large production units are the ones which utilize the most efficient production methods. 65 Economies of Scale, Learning and Combining 2. Economies of learning The economies of learning describe the phenomenon where the accumulation of production experience allows for improvements in the production process which in turn lead to the reduction of the production cost. This phenomenon is particularly linked to the production of complex products, in which other simpler products can be incorporated, where the coordination of quality, quantity and the attainment of outmost accuracy form a complex venture which is smoothed out along the practice, repetition and learning. The production of airplanes and computers form typical examples of this case. 66 Economies of Scale, Learning and Combining 3. Economies of combining The economies of combining describe the phenomenon where the production of a product favours the production of another product, so that their coproduction cost is smaller than the addition of the costs, if the production of each product were to take place separately. A baker, for example, can expand his production in a profitable way to pastry products because his knowledge and equipment are offered for this activity. The expansion of the companies of electronic computers to telecommunications explains also the emergence of this phenomenon. The economies of combining force the company to analyse, not only the profitability of a product, but also the profitability of activities which can be combined. 67 Questions 1. Describe, how cost affects the choice of size of a production unit. 2. Explain the relationship between the average cost curve and the marginal cost curve. 3. Define the difference between disbursed and incremental cost and utilize an example in order to make this distinction clearer. 4. Define the difference between accounting and economic cost. What are the consequences of this distinction on business decision making? 5. Describe the procedure of the break even analysis. 6. Distinguish between economies of scale, learning and combining. 68 Questions 7. Under what conditions can a business expansion be a combination of all the above economies? 8. The degree of operational leverage forms a significant factor for business decision making, particularly those related to the structure of the production unit and the proportional use of the production factors. Express your views on that. 9. How does depreciation affect a company’s break even analysis? 10. In the choice of the size of a production unit, an important factor that should be taken into account refers to the flexibility in large variations in production quantity. Do you agree or disagree? Express your opinion on that. 69 Exercises 1. DANUBE S.A. deals with the trade of legumes. It purchases in advance 1000 tones annually at pre-agreed prices, paying the producers 20% in cash and the rest in promissory notes which are redeemed following the sale of the product. This year the total purchase value is 30,000 euros. The warehousing for the product costs 3,000 euros and is prepaid by DANUBE S.A. The company faces three choices for the sale of the product. 70 Exercises Sale of the product at the domestic market with a guaranteed price of 24 euros per ton. b) Sale of the product at the European market where the price can range (with equal probability) to 24 euros or 36 euros per ton, on the basis of current expectations. c) Sale to the Asian market, where the price can range with equal probability to 12 euros or 50 euros per ton, on the basis of current expectations. a) 71 Exercises DANUBE S.A. has to settle, now, the transportation of the product which is to be sold to only one of the above markets. Which choice should the company adopt? Which choice should the legume producers prefer? Which choice should the company prefer, if it was wholly owned by one shareholder only with a total worth of 60,000 euros? • 72 Exercises 2. Two total cost functions are given: TC1 2,000,000 150Q 0.02Q 2 TC2 2,250,000 200Q 0.01Q a) b) c) 2 Derive the marginal and average cost function for each case. Determine the production limit where scale economies are exhausted for each cost function. Compare the two cost functions. 73 Exercises 3. Three postgraduate students of business economics at Munich University, plan their summer work. One possibility for them is to work for a local bank with a total three month salary of 8,000 euros for each one of them. The other is to organise a summer canteen for the sale of ice cream in a zoo. A kiosk and its full equipment is rented at the zoo, for 16,000 euros for a three month period. An additional cost of 2,000 euros is needed for the insurance of the installation and 0.80 euros per ice cream. 74 Exercises a) b) c) Derive the cost function. Which is the opportunity cost of the canteen business? Which is the break even quantity point? 75 Exercises Two companies A and B, plan the production of the same product by using different technologies. The sale price is 20 euros and the production capabilities range from 20,000 to 160,000 units per company. The cost data is: Company A: FC = 200,000, AVC = 15 Company B: FC = 600,000, AVC = 10 4. 76 Exercises a) b) c) Derive the break even quantity for each company. Estimate DOL for 80,000 and 120,000 units for A and B. Assume that the product price changes according to the demand function P = 30 0.00025Q. How are the previous calculations adjusted (Assume that each company ignores the existence of the other). 77 Exercises 5. a) b) The price function for the product that a company produces is: P = 40 - 0.000006Q, while the cost function is TC = 1,562,500 +20Q + 0.000004Q2. Which is the profit maximizing quantity? Which is the price and the cost per unit in the above quantity? 78 Exercises 6. The Agricultural Cooperative of Chania (ASX) has asked for a bid of offers for the transportation of 100 tones of products to Thessaloniki, in September. This transportation is taking place with lorries. The minimum time for loading, travel, unloading and return is 48 hours. Two types of lorries are offered, as follows: 79 Exercises Type Capacity Travel costs Loading costs A 2 tons 73,000 euros 8,000 euros B 5 tons 101,000 euros 20,000 euros Two transport companies are preparing their offers setting a price equivalent to cost plus 20% profit. Company DEF plans to rent lorries. The monthly rent equals 150,000 euros for type A and 400,000 euros for type B. Company XYZ owes lorries of type A, which the company intends to use. As the possibility of damages or delays exists in sea transport, each company foresees a spare a capacity of at least 20% in its offer. Which is the most economic offer of each company? 80 Exercises 7. OLYMPUS S.A. produces two products A and B for which relevant data for the past month, are as follows: Sales (units) Price per unit (€) Materials cost (€) Labour cost (€) Overheads (€) A 420,000 2.50 193,200 264,600 283,946.5 B 110,000 4.25 52,800 138,600 148,733.5 81 Exercises OLYMPUS is operating at full capacity but is unable to meet the demand for product A, which is half a million units per month. One way to meet demand for A is to reduce the output of product B and shift these resources to the production of A. For each unit reduction in B, OLYMPUS produces two units of A. Note that the average variable costs are constant in both production processes. 82 Exercises Alternatively, OLYMPUS could contract out to have product A manufactured by another firm in the same industry and sold as if this product were from OLYMPUS plant. KENTAVROS S.A. which has excess capacity is willing to supply 80,000 units of A at a price of €2.25 per unit. How should OLYMPUS resolve this problem? Support your answer with the discussion of the various issues involved. 83 Exercises 8. The following table depicts combinations of inflows for the production of 100, 200 and 300 units of a product. Method A B C D E F Inflow 1: capital 9 14 16 20 21 26 Inflow 2: labour 15 13 20 16 25 22 Product 100 100 200 200 300 300 84 Exercises a) b) If the remuneration for each unit of labour is €10.00 and for each unit of the capital €5.00, which is the combination with the lowest possible cost for the production of each production level? Does the company opt for techniques of more or less capital intensity? Please, explain. 85 Exercises 9. Explain why the degree of operational leverage (DOL) forms a basic factor in business decision making, particularly for those decisions which are linked to the structure of the production unit and the proportion of the production factors used. Furthermore, are there any disadvantages in the use of DOL? 86 Exercises 10. A company functions inside a competitive sector facing a fixed cost of 4 thousand euros and a variable cost presented below (in 000 euros). Production quantity (q) Variable cost (VC) 1 22 2 27 3 31 4 38 5 48 6 56 7 68 8 81 87 Exercises a) b) Estimate, TC, AVC, AFC, ATC and MC. Given that the company’s supply curve is formed as the part of the MC curve that is above the AVC curve, determine the supply curve of the company (the pricequantity combination). 88 Solutions to Exercises Exercise 1 The company pays in advance: 20% x 30,000 = € 6,000 The remaining amount (€30,000 - €6,000) = € 24,000 forms an obligation Warehouse cost: €3,000 Choice A (Full Certainty) DANUBE S.A. Revenues: 24 x 1,000 = €24,000 Payment: - 24,000 Net Return: 0 Average Return: 0 Suppliers +24,000 90 Exercise 1 Choice B (Low Risk and Return) DANUBE S.A Revenues: 24 x 1,000 = 24,000 36 x 1,000 = 36,000 Payment: - 24,000 Net Return: 0 12,000 Average Return: 0 + 12,000 / 2 = 6,000 Suppliers + 24,000 91 Exercise 1 Choice C (Low Risk and Return) DANUBE S.A Revenues: 12,000 50,000 Payment: 12,000 24,000 Net Return: 0 26,000 Average Return: (0 + 26,000) / 2 = 13,000 Suppliers 12,000 24,000 92 Exercise 1 Decision The company opts for C. (The company is an S.A. where the owners’ responsibility reaches the amount of their contribution to the share capital. Therefore, a possible loss may not shut the company down, immediately, as part of it can be undertaken by the shareholders. The suppliers opt for A or B. The only owner would opt for B. Note: It is clear that, the behavior of the investor towards risk should be taken into account, each time. 93 a) Exercise 2 AC1 = TC1/Q = 2,000,000/Q + 150 + 0.02 Q AC2 = TC2/Q = 2,250,000/Q + 200 + 0.01 Q MC1 = dTC1/dQ = 150 + 0.04Q MC2 = dTC2/dQ = 200 + 0.02Q b) Each function encompasses economies of scale up to the point of AC minimization. dAC1/dQ= -2,000,000/Q2+0.02=0 => Q1=10,000 dAC2/dQ= -2,250,000/Q2+0.01=0 => Q2=15,000 The 2nd function encompasses economies of scale at a larger 94 production limit. Exercise 2 c) At the two minimization points, we have: AC1 AC2 Quantity 10,000 550 525 Quantity 15,000 583.33 500 Observation At the range [10,000, 15,000], the second is the most effective function, as it presents the smaller AC and therefore it is more preferable. 95 Exercise 3 a,b) TC = FC + VC TC = (16,000 + 2,000 + 24,000 = fixed cost + opportunity cost) + 0.80Q TC = 42,000 + 0.80Q c) Q* = TC / (P-AVC) = 42,000 / (2-0.80) = 42,000 / 1.20 = 35,000 ice creams Therefore, 35,000 ice creams must be sold in order to cover the total cost of the canteen. 96 Exercise 4 a) Q1* = 200,000 / (20-15) = 40,000 units Q2* = 600,000 / (20-10) = 60,000 units Labour Intensive Capital intensive 97 Exercise 4 b) DOLa (at 80,000) = [Q*(P-AVC)] /[Q*(P-AVC) – FC] = 2 DOLb (at 80,000) = 4 (keep in mind, FCa < FCb) DOLa (at 120,000) = 1,5 DOLb (at 120,000) = 2 Note: DOL is always higher for higher capital intensive techniques. 98 Exercise 4 c) K = P x Q – AVC x Q – FC = (30-O.00025Q) x Q – AVC x Q – FC And DOL now is, DOL = [ dK / dQ ] x [Q/K] DOL = [ Q* x (P-AVC] / [Q*(P-AVC)-FC] By proceeding with the appropriate substitutions, DOLa (Q=80,000)=… DOLa (Q=120,000)=… DOLb (Q=80,000)=… DOLb (Q=120,000)=… or 99 Exercise 5 a) K= (40-0.000006Q)xQ-1,562,500-20Q0.000004Q2 K= 20Q+0.00001Q2-1,562,500 Proceeding to the derivative of this function with respect to Q and equalizing to 0, we have: d K /d Q = 0 Q * = 1,000,000 units 100 Exercise 5 b) Hence, the price P* = 40 – 0.000006Q = €34 AC=TC/Q= € 25.56 101 Exercise 6 Type A (2T capacity) 15 routes (maximum number within a month) transports 30 tones. The 4 Type A transport 120 tones (20% of spare capacity). Type B (5T capacity) 15 routes (maximum number within 1 month) transports 75 tones. The 2 Type B transport150 tones (20% spare capacity). Monthly rent: 150,000 Minimum time for loading, route, unloading and return: 2 days (48 hours). Then, we estimate the cost for each combination of lorries (it should be noted that many such combinations can take place, keeping in mind the spare capacity of each lorry). 102 Exercise 6 For the 4 As: Number of Routes 100 tons / 2 = 50 routes Rent 4 x 150,000 = 600,000 Route – Loading 50 x (73,000 + 8,000) = 50 x 81,000 = 4,050,000 Total cost for As: 4,050,000 + 600,000 = 4,650,000 For the 2 Bs: Number of Routes 100 tons / 5 = 20 routes Rent 2 x 400,000 = 800,000 Route – Loading 20 x (101,000 + 20,000) = 20 x (121,000) = 2,420,000 Total cost for Bs: 2,420,000 + 800,000 = 3,220,000 103 Exercise 6 Offer of XYZ: (It possesses four owned type A lorries): 4,650,000 x 1.20 = 5,580,000 Note: we include the rental cost, despite the lorries being owned by XYZ, as it forms the opportunity cost, as the fact remains that it could (potentially) rent them. In other words, it is a lost opportunity cost. One case could be, that XYZ does not include the 600,000 and therefore the offer would be stand at 4,050,000 x 1.20 = 4,860,000 104 Exercise 6 Offer by DEF. (It does not possess owned lorries). 3,220,000 x 1.20 = 3,864,000 It is therefore the lowest offer and could be selected, as this choice dominates. This forms a threat for XYZ, which would rather not stay stand still. It could rent the four Type A lorries (for some use) and follow, too, the selection of 2B, or proceed to an even better offer. Another combination could be lorries of both Type A and B: 1B + 2A (=75+60=135 tons) with a 35 % spare capacity. Solution 2B is more competitive even from 1B + 2A (proceed to the necessary calculations). 105 Exercise 7 Need to purchase 80,000 units of A. Therefore, A. Reduce B by 40,000 units Then: • Reduction in materials cost of B by (52,800/ 110,000)*40,000= 0.48*40,000=19,200 • Reduction in labor cost of B by (138,600/ 110,000)*40,000= =1.260*40,000= 50,400 • Reduction in revenues of B by 40,000*4.25= 170,000 • Reduction in overheads by (148,773.3/110,000)*40,000= 1.352*40,000= 54,085 106 Exercise 7 Net result of B: 19,200+ 50,400+ 54,085- 170,000= = -46,315 • Increase in materials cost of A by (193,200/ 420,000)*80,000= =0.46*80,000= 36,800 • Increase in labor cost of A by (264,600/420,000)*80,000= =0.63*80,000= 50,400 • Increase in revenues of A by 80,000*2.5= 200,000 • Increase in overheads by (283,946.5/ 420,000)* 80,000= =0.676* 80,000= 54,085 107 Exercise 7 Net result of A: 200,000- 50,400-36,800-54,085=59,115 • Net overall result: 59,115- 46,315= =12,800 B. Cost: 80,000*2.25 = 180,000 Revenues: 80,000x2.50 = 200,000 Net result: 200,000-180,000 = 20,000 Suggestion: Buy rather than make. 108 Exercise 8 a) Method A B C D E F Quantity of K 9 14 16 20 21 26 Value of K 45 70 80 100 105 130 Quantity of L 15 13 20 16 25 22 Value of L 150 130 200 160 250 220 Product (units) 100 100 200 200 300 300 TC AC 195 200 280 260 355 360 1.95 2.00 1.40 1.30 1.18 1.17 109 Exercise 8 Therefore, • for production level of 100 units A is preferable. • for production level of 200 units D is preferable. • for production level of 300 units F is preferable. b) Along the rise of the product volume, AC is being reduced implying capital intensive techniques, and economies of scale. 110 Exercise 9 Useful in deciding on labour intensive versus capital intensive techniques. Also, comment on possible disadvantages of DOL. 111 Exercise 10 a) Firstly, TC (=FC+VC) is estimated and them follow other cost elements: q 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 FC 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 VC 0 22 27 31 38 46 56 68 81 TC 4 26 31 35 42 50 60 72 85 AFC 4 2 1.3 1.0 0.8 0.7 0.6 0.5 AVC 22 13.5 10.3 9.5 9.2 9.3 9.7 10.1 ATC 26 15.5 11.6 10.5 10 10 10.3 10.6 MC 22 5 4 7 8 10 12 13 112 Exercise 10 TC=FC+VC, AFC=FC/q, AVC=VC/q ATC=AFC+AVC, MC=TC(q)-TC(q-1) b) The supply curve of the company is determined as the part of the MC curve which is above the AVC curve. Therefore, the supply curve is composed of the following points: q P 6 10 7 12 8 13 113