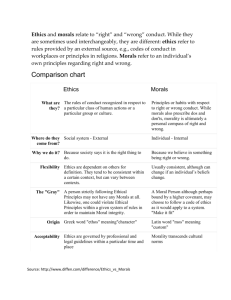

The underlying values and policies in good faith considerations are

advertisement

The European Bill of Fraud Erik Røsæg1 1 Introduction I think we all remember the English case about the shipowner who gave a clean bill of lading against a letter of indemnity in respect of leaking barrels of orange juice.2 I vividly can imagine the sticky, smelling mess which must have developed in the holds. The shipowner was made liable for the misdescription and had to pay damages to the receiver. He then turned to the shipper and demanded recourse under the letter of indemnity. The shipper argued that the courts should not enforce the indemnity – because he himself had been fraudulent! The court let him go free – they would not sort out matters between crooks. The end result was therefore that the court helped the culprit to keep the profit, while the shipowner had to carry the loss. Although the shipowner was clearly guilty of misdescription, I have some sympathy for him, because he would have been in a commercial squeeze and the problem did not originate at his end. The idea was however not to place the loss in the proper place. The point was to avoid tainting the court with determining a case between crooks. This is not a very peculiar English case. It is well in line with a Roman law tradition: Ex turpi causa non oritur actio – the case is not heard because of fraud. That does not make it any better. The buck stops in the wrong place. The bill of lading has been allowed to become a bill of fraud. I think it is on high tide to rethink this approach. The ex turpi causa-issues form part of the larger problems of commercial courts and morals, reflected in more general doctrines such as contracts contra bonos mores and illegal contracts.3 For my part, I see no reason to in the outset distinguishing between the influence of morals leading to total unenforceability or invalidity, partial invalidity or policy-based construction of contracts. Unfortunately, DCFR and the others are not very helpful here.4 They do not address the matter face on. But despite the core of uniformity based on Roman law, the disparities and challenges are so 1 2 Some thoughts in this paper were discussed informally with international colleagues at the University of Pennsylvania in May 2014. I am very grateful for the inspiration and advice received in connection with this event. Brown Jenkinson v Percy Dalton [1957] 2 Lloyd's Rep 1. 3 MacQueen, Illegality and Immoraltiy in Contracts: Towards European Principles In: Hartkamp, Towards a European civil code (2004) p. 418 points out that concepts such as immorality, public policy and ordre public capture for many may distinct ideas and associations. 4 Vogenauer and Kleinheisterkamp, Commentary on the Unidroit principles of international commercial contracts (PICC) (2009) p. 402; Bar and Clive, Principles, definitions and model rules of European private law: Draft Common Frame of Reference (DCFR) (2009) p. 40. The principles of European Contract law (PECL) include some provisions of the effect if illegality, etc. in Chapter 15, but leaves the issue of what is illegal, etc. to national law (http://www.jus.uio.no/lm/eu.contract.principles.parts.1.to.3.2002/). The 1 great that it is difficult to avoid the topic in the future discussions. This may be due to a lack of a common European legal culture.5 In the framework of the Common Core project, there are some discussions that certainly could influence maritime law in the future,6 and apparently one is still working on this in the context of the European Principles.7 The problems are not peculiar to maritime law and practice, although there is an abundance of examples here. But this would be a good arena for mutual influence between the maritime law and practice on the one side and general contract law and practice on the other. To use the same words as before in a different meaning: we need a European Bill of fraud. In the following, the new morals will be exemplified (below 2) and the basic rules of contra bonos mores and public policy will be discussed (below 3). Thereafter, 20th century developments will be discussed: The introduction of the concept of good faith is a major development in this context, but it has its limitations (below 4). To a great extent, the legislators have intervened, but the interventions have rather crude effects on contracts and are not of a general nature (below 5). Finally, a strategy to deal with the problem will be outlined (below 6). 2 The new morals The morals of our time are a-changing. There are, however, methodological problems involved if one wishes to ascertain this more exactly. One example will suffice to demonstrate the radical changes in moral thinking: In my lifetime, there has been a very radical change in the view on abortion – now virtually uncontroversial and irreversible in most of Europe. It is hardly possible to pinpoint the changes in facts or values that have caused the U-turn; this is not a matter of stringent logic or clear choices of values. All I really know is that attitudes change, and perhaps we change with them. I must confess I often consider newspapers a good barometer of what the prevailing public morals are. The papers know their readers, and they strongly influence them. A matter that is more or less explicitly held out to be a wrongdoing in the newspapers is likely to reflect an attitude in public morals. It is at least a better source than my own feeling. If and when a prevailing moral attitude has been ascertained, it is obviously not so that the courts should act on any change in public moral. But there are several examples of moral issues that are so pivotal that one at least should consider whether the courts should continue to ignore them. My first tentative observation to illustrate the new morals is how we now think about prostitution. From being objectionable and unenforceable because it does not confine sexuality to the boundaries of marriage and because it represent non-restraint of lust, it is now more common to see this as 5 6 7 EU has not taken up the issue, see A Common European Sales Law to Facilitate Cross-Border Transactions In The Single Market (COM(2011) 636 final) p. 8. Busch, The Principles of European contract law and Dutch law: a commentary (2002) p.192; LopezRodriguez, Ana M: Towards a European Civil Code without a common European legal culture? The link between law, language and culture In: 29 Brooklyn Journal of International Law (2004) p. 1195-1220, who does not expressly mention illegality or immorality. See http://www.common-core.org/node/46. See the background work MacQueen l.c. p. 415 et seq. 2 morally objectionable suppression of the prostitute; in particular women prostitutes. Obviously this must have effects in contractual conflicts. Rather than rejecting to deal with the matter at all as being immoral, the courts must interfere, e.g. to make sure that a prostitute will get her remuneration if the act first is performed. The morale has changed, and so must the law. A second observation is the ethical or policy problem that is paramount for the entire planet: Greenhouse gas emissions. Should the courts really remain neutral to this issue, even if still controversial in some quarters? Obviously, not all contracts with a negative effect of global warning should be declared void. However, arguably the courts should have a freedom or indeed an obligation to interpret contracts in the lights of the new morale, so that, e.g., obligations to sail a ship with “due dispatch” should allow for energy saving slow steaming, at least if there is no evidence that the parties have intended something else. It may even be so that the courts should censor obviously damaging incentive structures. Thus in voyage charterparties, the incentive structure makes it economically viable for a shipowner to increase his speed in order to arrive early, so that the per hour port regime will apply. If the port (demurrage) rate is high, the speed will be increased even more. I submit that good, new morals demands that the courts should not enforce this environmentally unfriendly incentive system if there is no commercial purpose for it, e.g. because the port is congested anyway and early arrival does not secure earlier loading or discharge. A third area that has got new, moral attention is insurance and pollution. To me, it is quite obvious that major pollution incidents not only cause despair and sorrow, but also moral rage. Strong economic incentives are used to prevent pollution incidents. But should the courts allow that these incentives are neutralized by insurance covering liability and even fines? A classic example of this kind is P&I Clubs’ covering members’ fines under an omnibus clause, at least if they do not consider the treatment fair in the jurisdiction in question. Or one can recall the ship that exported waste from Mexico via the US and Europe to Cote d’Ivoir, processed the waste and deposited the waste in Abidjan, causing injury to a large number of locals.8 The entire operation was on the edge of the law. So should the responsible party be allowed to recover on whatever liability insurance was applicable? There is a long way from finding that the operation is dubious to that it is illegal. The law perhaps should not react as long as the immorality is not also illegality. A final example is the concern not only of what you get as a contractual performance, but how it is brought about. A container of perfect clothing is perhaps not good enough if it is made by child labor of black labor. And the performance of a carrier or an entrepreneur is not good enough if risks are taken in the performance of the contract.9 Good morals require that the receiver cannot any longer just look at the end result, but must also consider the process behind it. But I do not know any court of law that will think along these lines unless there is an explicit contract to this effect. 8 9 Probo Koala, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2006_Ivory_Coast_toxic_waste_dump. In the English case St John Shipping Corporation v Joseph Rank Ltd [1957] 1 QB 267, Devlin J held that the purpose of the statute on overloading ships did not prevent enforceability of a carriage contract, perhaps contrary to what is suggested here. 3 The point of these examples is to demonstrate that what causes moral concern today may not be adequately addressed by the law. There is a difference between law and moral, but it is likely that that this dichotomy is not the problem here. But these morals are not of another kind or another strength than those already incorporated. The problem is rather that the morals and policies incorporated into the law of contract do not include the new morals. The problem of not taking notice of new moral concerns reaches beyond having suboptimal laws. By enforcing the condonable practices of the parties, the court itself gets tainted. Enforcing the new morals is as necessary for the courts as for the society as a whole. 3 The basic rules – same examples Many jurisdictions have rules on fraud, illegality and immorality. Here I will give three very different examples.10 3.1 Norway In Norway, there is a section in an act from 1667 providing that contracts against decency and law are exceptions to the main rule of pacta sunt servanda.11 The courts have not been very eager to use this provision, although it is accepted that this “standard” can refer to all kinds of morals and is flexible over time.12 Neither illegality nor contra bonos mores are therefore of great importance in Norwegian contract law. There is a general provision in the Contracts Act, s. 36 that allows courts to set aside and modify unreasonable contracts.13 This provision is rather open ended. However, there are no examples in Norway that the provision has been used when the problem is that the contract is unreasonable in relation to third parties or more abstract values. The core of the provision is to preserve a fair bargain between the parties. This is, of course, also a moral issue, but quite limited in scope. In interpreting contracts, the Norwegian courts are quite liberal in relation to the wording.14 Implicit assumptions may be relevant if they fail,15 and terms are freely implied. This, of course, also includes a possibility to include new morals in the arguments. In Rt-2006-179, the Supreme Court considered whether a consumer buyer of boots could demand new boots or only repair when the heel fell off. The court considered whether the cost of new boots to NOK 465 would be an “unreasonable expense” for the seller when the boots could be repaired for NOK 65. The majority concluded against the consumer’s demand for new boots with explicit reference to environmental considerations. The cost of new boots was in itself hardy unreasonable. But the court emphasized that if the boots were not repaired, they would most likely be thrown away, as there was no second hand marked for boots. Therefore, the majority explained, 10 11 12 13 14 15 For others see The Dutch Civil Code Art 3:40 (Busch l.c. p. 191); BGB Articles 134 and 138; CC Articles 6, 1128, 1131, 1132 and 1133. Woxholth, Avtalerett (2009) p. 332 et seq. The term «standard» is usually attributed to Knoph, Rettslige standarder: særlig Grunnlovens §97 (1948). Woxholth l.c. p. 340 et seq. Woxholth l.c. p. 395 et seq. Hagstrøm, Obligasjonsrett (2011) p. 260 et seq. 4 environmental considerations (not throwing away things) should influence the view on whether redelivery would be an unreasonable cost for the seller. As always in Norwegian sales law, it is difficult to say clearly whether the Court construed the Consumer Sales Act or the individual contract of sale. As usual, the individual contract gave no guidance. But in any event it is clear that the majority in the court felt free to introduce new, environmental morals into the sales relationship, to some extent supported by the literature and the parliamentary debate leading up to the enactment. In my view, this is a remarkable example to be followed. However, it also reflects that the more arguments are allowed, the more difficult it gets. It may very well be that the better environmental effects would have been to impose the harsher sanction to the sellers, so that he would produce boots of better quality in the future, less likely to end early in the trash. 3.2 England In England, the courts keep quite strictly to the wording of contracts, and the public policy exception is in practice limited to certain heads in order to ensure foreseeability.16 Illegal contracts include agreements by married persons to marry, agreements on trading with the enemy, contracts to deceive public authorities and champerty (agreements to finance another person’s litigation in return for a share in the proceeds). A big head is contracts in restraint of trade, still living alongside European competition law. To a great extent, these heads seems to have been developed by historical coincides and never removed. Although the heads of illegality can be justified, they are certainly not responses to the new morale issues. 3.3 US In the US, the rules on illegal and immoral contracts are quite open:17 § 178 When a Term Is Unenforceable on Grounds of Public Policy (1) A promise or other term of an agreement is unenforceable on grounds of public policy if legislation provides that it is unenforceable or the interest in its enforcement is clearly outweighed in the circumstances by a public policy against the enforcement of such terms. (2) In weighing the interest in the enforcement of a term, account is taken of(a) the parties' justified expectations,(b) any forfeiture that would result if enforcement were denied, and(c) any special public interest in the enforcement of the particular term. (3) In weighing a public policy against enforcement of a term, account is taken of(a) the strength of that policy as manifested by legislation or judicial decisions,(b) the likelihood that 16 17 See to this and the following Peel and Treitel, The law of contract (2011) p. 470 et seq. and Manchuk: Armed Guards, Marine Insurance, and the Implied Warranty of Legality In: 24 University of San Francisco Maritime Law Journal 309 (2011-12) p. 321-47. The ex turpi exception is also used to justify non-payments under letters of credit in case of fraud, see most recently Antoniou: Nullities in letters of credit: extending the fraud exception In: 29 Journal of International Banking Law and Regulation 229 (2014) p. 231. Restatement (Second) of Contracts, § 179. 5 a refusal to enforce the term will further that policy,(c) the seriousness of any misconduct involved and the extent to which it was deliberate, and(d) the directness of the connection between that misconduct and the term. The focus is protection of the public welfare: § 179 Bases of Public Policies Against Enforcement A public policy against the enforcement of promises or other terms may be derived by the court from(a) legislation relevant to such a policy, or(b) the need to protect some aspect of the public welfare, as is the case for the judicial policies against, for example,(i) restraint of trade (§§ 186- 188),(ii) impairment of family relations (§§ 189- 191), and(iii) interference with other protected interests (§§ 192- 196, 356). In practice, the courts hesitate to introduce new heads of illegality.18 This is thought best left to the legislators.19 It is likely that a similar attitude applies in the construction of contracts. 4 Good faith A flexible instrument for implementing new morals is the concept of good faith. But while the principle of good faith is widely recognized, the tenor of it is rather uncertain, and parts of the private law may be more or less excluded from its scope.20 Legal systems differ greatly in this respect. There may also be differences of what is considered to fall inside the ambit of the good faith principle (or principles), and what falls outside. There is one particular aspect of good faith is relevant to this paper: The aspect involving policy, politics or morale. To which extent could the application of the good faith principle be influenced by what could be considered the common good? This is called antisocial exercise of rights in the translation of the Spanish Civil Code: Article 7 1. Rights must be exercised in accordance with the requirements of good faith 2. The law does not support abuse of rights or antisocial exercise thereof. Any act or omission which, as a result of the author's intention, its purpose or the circumstances in which it is performed manifestly exceeds the normal limits to exercise a right, with damage to a third party, shall give rise to the corresponding compensation and the adoption of judicial or administrative measures preventing persistence in such abuse. This aspect of good faith includes such policy matters as the enforcement of contracts for sexual services and contracts restraining free competition. 18 19 20 Restatement (Second) of Contracts § 179 (1981), Official Comment (b). Ibid. See to this and the following Zimmermann and Whittaker, Good faith in European contract law (2000). 6 In the European codification attempts, these aspects have, as already mentioned, been left out,21 perhaps because they the views are disparate and the matters feel unpleasantly politicized. In my view, these are important and necessary elements of good faith that cannot and should not be left out. The distinction between the good faith considerations included in the European projects and those not is unclear. Thus when PICC exclude “invalidity arising from … immorality or illegality”, it is not the “immorality or illegality” as used in BGB art. 138.22 The latter provision include gross disparity, which is dealt with in PICC and obviously not intended to be excluded. There is indeed no difference in principle between the included and the excluded parts of the good faith considerations. The protection of the weaker party when there is an unequal bargaining power is as much a policy consideration as (other) immoral contracts. The underlying values and policies in good faith considerations are as differentiated as the good faith considerations themselves. When disclosure in contract negotiations is required, the policy consideration is that it would be better when people know what they buy or perhaps that sellers should not make profit on inequality of information. When reservations are added to a clear contract, the underlying policy is perhaps that parties should not have to take all eventualities into account and provide for them in the contract. One may disagree in these policies or find that my suggested expressions of them are not the best. However, it is fairly clear that they are policies that at least some courts will consider. In one specific context this is less obvious than in the others; that is when the (non-negligent) good faith of one party is relevant even the other is not in bad faith. This is when a purchaser in good faith obtains possession of a movable, and thereby gets a better title than a previous purchaser. This may be a distinct and different use of the good faith concept altogether. Or one can say that the underlying policy is that purchaser should be able to trust what they can observe. This is not a particularly moral issue. It is typical for the good faith values that they are generally accepted, almost to the extent that one has to be a lawyer to prefer the strict law. And even those who feel that the strict law must prevail in all or some of the conflicts, would be likely to recognize the values of trust, openness etc. The values as such are not controversial or politicized. 5 Legislative interventions The need for court intervention decreases by increasing legislative intervention. Illustrative is the ever decreasing sizes of the commentaries to BGB Article 137 on good faith – Treu und Glauben – as the doctrines developed by the courts on the basis of the provision are overtaken by specific legislation. There are many examples of such intervention. It does resolve the problem of whether it is legitimate for the courts to take a certain view – perhaps based on new morals – into consideration. But the regulation of private law matters are often too rigid or otherwise not well thought out. Often, a 21 22 See fn. 4, above. Vogenauer and Kleinheisterkamp, l.c. p. 402. 7 better approach would be to leave this to lawyers with a private law focus and private law experience. One example is the legislation on genetic information. Many states require a good health reason to take a genetic test and have banned the use of genetic tests in insurance. Norway is one of them. I believe Norwegian legislators are neither better nor worse than others, and will use the Norwegian legislation as an example for analysis. Unfortunately, the analysis requires that contract lawyers go beyond the comfortable realm of pure contract law. It is certainly better than trusting health policymakers to work out the details of the law of contract. The Norwegian rule is that predictive tests cannot be used in insurance, as opposed to diagnostic tests. From a contract law point of view there are several shortcomings in this approach:23 First of all, there is little or no evidence that the legislators have considered the contractual consequences of making genetic information known to the insured illegal to use. This means that the insured can buy insurance against a serious illness he more or less knows he will get. The whole exercise of making an insurance contract then becomes meaningless. It would be much less bureaucratic to require insurers to donate to those suffered from genetic diseases, and that would benefit also those who for some reason do not insure against their genetically predicted fate. Secondly, it is not a good idea to regulate contract law on the basis of the distinction between diagnostic and predictive tests. This distinction stems from the regulations for taking tests, where it is meaningful, because the distinction refers to the purpose of taking the test. But in insurance, the issue is often secondary uses of tests already taken. As long as the test can be used for prediction, it is irrelevant what its original purpose was. Using the public law framework for regulating the law of contract is in this respect rather unsuccessful. Thirdly, while the public law primarily regulate DNA screening, also indirect ways of obtaining genetic information, such as family history and visible traits, are relevant to an insurer determining risk. Similarly, for an insurer the genetic traits is but one of many risk factors, while the public law does not address risk evaluation, but DNA tests. The legislator seems to have been aware of this, and adds a prohibition on asking whether family history has been taken. The addition is inadequate, and more than anything emphasizes how inappropriate it is to regulate contractual matters in a public law context. Fourthly, the weighing of interests may be different in public law and insurance law. In Norway an exception to the rigid regime for genetic tests has been made in respect of a routine test on all infants for Følling’s disease, probably for practical reasons.24 The unfortunate coupling with insurance 23 Norwegian Act No. 100/2003relating to the application of biotechnology in human medicine, etc. (translated at http://www.ub.uio.no/ujur/ulovdata/lov-20031205-100-eng.pdf) s. 5-8. See to the policy points in the following Forsikringsselskapers innhenting, bruk og lagring av helseopplysninger: innstilling fra et utvalg oppnevnt av Sosial- og helsedepartementet oktober 1998 : avgitt 4. juli 2000 (2000) Ch. 9. 24 See Helsedepartementet, Høringsnotat - Lov om medisinsk bruk av bioteknologi m.m. (November 2002) item 5.9.1. The 2003 Act has resolved the problem by a special provision om mass screenings. 8 law probably made the results of these tests available also for insurers, although there is no particular reason to make an exception to the general principle in this context. Finally, the geographical scope of the public law regulation of DNA tests and the contract law regulation of genetic information and family history in insurance are different. The starting point is that the regulation of genetic tests applies in Norway, while the insurance law applies when the insurance contract is governed by Norwegian law. There are exceptions to this. But it does not necessarily make sense to let the contract law ban on using tests apply when tests are freely available. Likewise, it may not make sense to wholly or partly invalidate an insurance contract with a foreign company which legally has calculated a high or low premium based on a genetic test only because Norwegian contract law applies, in particular if it applies by choice. Again, contract law should be analyzed separately form public law. There are also plenty of other examples on public law rules with a not so well thought out addition on private law effects. A classic example is the agreement on the International Monetary Fund Article VIII(2)(b): (b) Exchange contracts which involve the currency of any member and which are contrary to the exchange control regulations of that member maintained or imposed consistently with this Agreement shall be unenforceable in the territories of any member. This rule has caused a vast amount of literature due to its lack of clarity and sense, without such refinements as a distinction between partial and total invalidity or between substantial and minor violations.25 This definitely should have been left to experts on contract law. From a more recent trend, anti-discriminatory legislation could be mentioned as a final example. The courts can obviously not enforce contract clauses or property ownership restrictions that are illegal due to their discriminatory nature.26 At least in the Norwegian legislation, discrimination is defined quite well. But also aiding and abetting to discrimination is illegal. Which effects does that have on linked contracts, such as guarantees, bearing in mind that also “indirect discrimination” is illegal? Again, the legislator has created a rule on invalidity without considering its effects. In sum, I think it is safe to assume that private law effects of new morals and new policies should be worked out by lawyers specializing in private law. 6 A better strategy In my mind, there is no doubt that a better strategy should be developed concerning the new morals. It is not good for the courts to be seen enforcing contracts that are detrimental to the environment, to treat child labor as irrelevant, etc. These values are now so commonly accepted, at least in the 25 26 Røsæg, Garantier eller fattigmanns trøst? Støtteerklæringer i selskapsforhold av typen "comfort letters" (1992) p.435-456. Act No. 60/2013 on prohibition of discrimination based on ethnicity, religion, etc. §§ 6 and 12 (translated at http://www.regjeringen.no/en/doc/laws/Acts/the-act-on-prohibition-ofdiscrimination.html?id=449184). 9 Norwegian society, that the foreseeability of contractual parties and the neutrality of the courts hardy can justify that courts do not take issue when called for to do so. It is an advantage for contractual parties to have a great deal of foreseeability, so that contracts are taken at face value. But this is not the only value that is important. And unlike very may other unexpected events in the life of a contract, a court intervening on the basis of new moral on which there is a broad consensus is a foreseeable un-foreseeability. A party who is unaware of the objectionable factual circumstances will be protected to the same extent as if the illegality was imposed by a clear Act of Congress. And he can hardy complain that he could not position himself in respect of the illegality; on the assumption of good faith he would not have done so anyway. In Europe, the approaches vary. This is a problem for the internal European market. To some extent foreseeability can be achieved by choice of law and jurisdiction. But in particular jurisdiction may end up in another state than intended, and the courts of that state may not easily depart from its deep rooted attitudes to morals and public policy. This means that a uniform European approach is necessary for the common European market. Finally, these matters should not be left with the legislators. The legislators may have a good grasp on the facts, although this is not always so. But their contractual analysis is not necessarily so good. The courts should therefore have the possibility to use or not to use invalidity and value-based construction in their handling of contracts on the borderline of new or old morals. In particular this is so when the matters are too complex to deal with in legislation, as in some of the examples above. 10