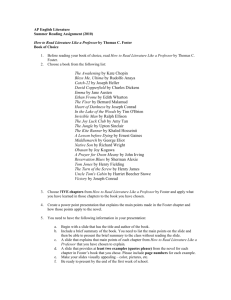

Foster Care Outcomes

advertisement

Foster Care Outcomes: Does Foster Care Help or Harm Children’s Emotional and Social Development? Dee Wilson Presentation to CA Medical Consultants March 17, 2008 Many foster care placements last for brief periods of time; median length of stay (LOS) for CPS placements in Washington State is about 1 year. However, approximately one quarter of children in out-of-home care for at least 60 days in Washington State are still in care 3 years after their date of placement. 2 Surveys of foster children around the world almost always elicit highly favorable views of foster care. “We are apparently in the presence of a robust phenomenon that does not appear to be either sample specific or country specific.” (Flynn, Robitaille, & Ghazal, 2006) 3 The odds of a child being reunified with birth parents decline dramatically as length of stay (LOS) increases. 4 Children with behavioral problems have much lower reunification rates than children without behavior problems. (Landsverk, et al, 1996) 5 One-half to two-thirds of children in out-of-home care have serious mental health problems; only 25% of children with MH problems receive MH treatment. Source: National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being 6 Long LOS are associated with multiple placements. Almost half of children in care for 4 or more years in Washington State have had 5 or more placements. 7 Placement disruptions are not the same as placement moves. Some of the best recent research has classified children as achieving “early stability,” “late stability,” “variable stability,” or “unstable” instead of counting placement events. (Rubin, et al, 2007) 8 In one recently published Australian study, 20% of foster youth were found to be “homeless in care”. Barber & Delfabbro (2006) refer to the “truly wretched conditions under which these foster children live.” 9 Both Rubin, et al (USA, 2007) and Barber & Delfabbro (Australia, 2006) found that approximately 20% of children in foster care were “unstable” in care at 18 months to 2 years after date of placement. Rubin, et al found that almost one-third of children 10 and older were still unstable in care at 18 months after original placement date. 10 The National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being (NSCAW) has found that “placement stability over the first eighteen months was significantly related to all permanency outcomes…” (Rubin, et al, 2007) 11 In NSCAW, “regardless of a child’s baseline risk for instability in this study, those children who failed to achieve placement stability were estimated to have a 36% to 63% increased risk of behavioral problems compared with children who achieved any stability in foster care.” (Rubin, et al, 2007) 12 Ryan & Testa (2005) found that male youth with 3 placements were 1.54 times more likely to be found delinquent in the Illinois Juvenile Justice System than male youth with 1 placement; male youth with 4 placements were 2.13 times more likely to be found delinquent than youth with 1 placement. The CPS substantiation history of children/youth was also related to delinquency (the greater the number of substantiated CPS reports the greater the odds of delinquency). Youth placed out of the home were 1.89 times more likely to be engaged in delinquent acts than youth remaining in the home. 13 Ryan & Testa comment that “the home environment for children removed from parental custody is unquestionably more deleterious compared to maltreated children whose environment is deemed safe enough for them to remain at home.” However, they add, “removing children from these highrisk environments should decrease the risk of delinquency. But our findings are that children in placement are more likely to be delinquent.” Ryan & Testa assert that placement instability is a major reason why out-of-home care often fails to have a therapeutic effect for male youth. 14 The NSCAW found that adolescent delinquent behavior for youth in out-of-home care was fairly stable over the first 18 months of placement. 15 Lawrance, Carlson, & Egeland (2006) compared 46 children, 0-9 at entry into care, to 46 maltreated children who remained at home in a longitudinal study. Developmental outcomes for these children were compared to 97 non-maltreated children. Children who had been in foster care had more behavior problems immediately after exit from care than maltreated children who had not been placed out of the home. Adolescent outcomes did not differ for the placed vs. nonplaced maltreated children. Both groups increased in behavior problems as children became older. Children placed in kin foster homes had less internalizing problems at exit from care than children placed in non-kin homes. 16 Rubin, et al’s (2007) analysis of the National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being (NSCAW) found that the strongest predictor of a child’s behavioral adjustment 18 months after entering care was the child’s level of behavioral problems at entry into care. Younger, healthier children with few behavior problems at entry into care had the best behavioral outcomes. Most children with poor CBCL scores at baseline had abnormal scores 18 months later, even when these children had stable placements. 17 The NSCAW indicates that in the aggregate foster care does not markedly improve or harm children’s functioning for most behaviorally troubled children. 18 However, aggregate trends for children in care mask considerable variability in children’s developmental outcomes. Three factors which mediate these differences are: Children’s behavior problems at entry into care, Children’s placement histories, and The quality of children’s relationship with substitute caregivers which are, in turn, affected by caregiver characteristics such as emotional warmth, acceptance, skills in managing children’s behavior, and commitment to the child. (Rubin et al, 2007; Shlonsky & Berrick, 2001) 19 The evidence continues to mount that exposure to chronic maltreatment has devastating effects on children’s development. In his recently published (2008) study of 347 foster children 4-9 years of age in New South Wales, Australia, TarrenSweeney found that length of exposure to chronic maltreatment prior to entry into care was the major factor influencing children’s mental health status. Tarren-Sweeney asserts that “longer time in care was protective” (of children’s development), even though almost 20% of the foster children had been abused or neglected in care. 20 Caregiver Report of Severe Violence Conflict Tactics Scale Parent to Child version Severe violence sub-scale hit child with fist or kicked him or her grabbed child around neck and choked him or her beat child up burned or scalded child hit child with a hard object on some other part of the body besides bottom threw or knocked child down Limited to children who remained in home following the investigation for maltreatment (Barth, 2005) 21 Caregiver Report of Severe Violence Infants/Toddlers (0-2) 5 1 6 88% None Worsened Preschoolers (3-5) 4 7 3 86% None Worsened Improved Continued Improved Continued (Barth, 2005) 22 Caregiver Report of Severe Violence (2) Middle Childhood (6-10) 10 Adolescents (11+) 42 6 5 12 85% None Worsened 77% Improved Continued None Worsened Improved Continued Among children older than 6, a significantly higher proportion had a decreased incidence of severe violence at 18 month than an increased incidence (6-10, p < .01; 11+, p < .05) (Barth, 2005) 23 Probability of Experiencing Severe Violence 0.12 0.1 Baseline 18 months 0.08 .12 .09 .08 .08 0.06 .07 .06 0.04 0.02 0 3 6 Violence increases in the lives of the youngest children, then begins to decrease in middle childhood 10 Age in years* (Barth, 2005) 24 Caregiver Report of Severe Violence and Official Re-report of Maltreatment for In-home Children Proportion of all caregivers reporting severe violence at 18 months % (SE) Proportion of caregivers reporting severe violence with an official re-report by 18 months % (SE) 0-2 (n=1006) 4.9 (1.3) 8.7 (7.6) 3-5 (n=497) 10.5 (2.9) 25.4 (11.4) 6-10 (n=790) 5.6 (1.1) 39.4 (9.6) 11+ (n=601) 10.2 (2.4) 31.1 (10.6) Total (n=935) 7.6 (1.1) 28.9 (5.0) All analyses are on weighted data, Ns are unweighted. • Among caregivers of infants and toddlers who reported using severe violence at 18 months, less than 9% had an official re-report of child maltreatment. • Overall, of those children with caregiver reported severe violence, 29% had an official re-report. (Barth, 2005) 25 Conclusions: Re-Report Although the majority of re-reports are not substantiated, about one in five children has at least one re-report over the 18 months Children in out-of-home care still have some risk of recurrent maltreatment Possible explanations for maltreatment include: occurred prior to child entering foster care occurred during visit with biological family child on child maltreatment in foster or group home (Barth, 2005) 26 Conclusions: Re-Report Receipt of parenting services associated with increased likelihood or re-report Possible explanations include: Families with greater needs selected into services Agency surveillance Services do not adequately family needs (Barth, 2005) 27 Caregiver Report of Violent Parenting Tactics Many caregivers (8%) report using severe violence toward their child following child welfare involvement A large proportion of severe violence remains unreported. This is especially true for infants and toddlers. Violence between intimate partners often leads to an increase in the amount of severe violence children experience (Barth, 2005) 28 In addition, there are some studies which indicate that foster children make better progress on standard developmental measures than reunified children. 29 (Bellamy, 2008) 30 Bellamy’s analysis (2008) of NSCAW data for 604 children in foster care for longer than 8 months found a small overall decline in CBCL scores while reunified children had a fourfold increase in internalizing behavior problems at 18 month follow-up. 31 Bellamy found that reunification outcomes for children were mediated by caregivers’ mental health and overall family stress, rather than by reunification per se. Bellamy also found that “continued long-term foster care does not inherently worsen this high-risk group’s behavioral health over time." 32 Taussig, Clyman, & Landsverk’s (2001) study of 149 ethnically diverse children 7-12 years of age in foster care for at least 5 months in San Diego found that “youth who reunify with their biological families after placement in foster care have more behavioral and emotional health problems than youth who do not reunify.” “These findings were consistent across the range of outcomes examined: Engagement in risk behaviors, life course outcomes, and current emotional and behavioral symptomatology.” 33 The non-reunified youth in Taussig, et al’s study had experienced an average of 8 placements after 6 years in care. These researchers could locate only 62% of reunified youth for the follow-up interview. 34 20-30% of children reunified with birth parents re-enter out-of-home care within 3-5 years. For many foster children, placement instability does not stop with return to birth parents. 35 One possible interpretation of NSCAW findings regarding out-of-home care is that foster care for behaviorally-troubled children is neither especially therapeutic nor harmful, unless children have highly unstable placement histories. However, the single most distressing NSCAW findings regarding out-of-home care concern infants and toddlers. 36 National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being (NSCAW) Infants did worse on developmental measures after 18 months in care. Bayley Infant Neurodevelopmental Screener (BINS) Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (VABS) Battelle Developmental Inventory (BDI) Preschool Language Scale (PLS-3) 37 Developmental Measures in NSCAW Bayley Infant Neurodevelopmental Screener (BINS) Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (VABS) Battelle Developmental Inventory (BDI) Preschool Language Scale (PLS-3) 38 Infants (0-3): Overall Change Over 18 Months Average Score at 18-Months: Measure BINS 6.1 0.5 VABS 89.6 -9 BDI -2.26 PLS-3 42.2 -5.73 -10 -8 -6 88.1 -4 -2 0 2 Change in points (Barth, 2005) 39 Infants (0-3): Age as a Significant Predictor Measure BINS Younger infants are much more likely to show greater deterioration 2.25 -0.08 -1.66 VABS 0.87 -7.61 -15.58 1.48 BDI -1.99 -5.42 PLS-3 0.51 -4.69 -9.78 -20 -15 -10 -5 0 5 Change in points Youngest 50th percentile Oldest (Barth, 2005) 40 Summary: Age 0-2 No significant measured improvements in development for infants In general, infants < 2 years decline in all measures, those 25-35 months improve Children with lower HOME-SF scores see greater declines in three of the four measures Children in nonurban PSUs see higher risk for developmental delay and neurological impairment and worsening language skills Males decline in cognitive development and social skills (Barth, 2005) 41 Summary: Age 3-5 Slight decline in social skills; improvement in language skills; stable level of problem behavior Age in months is a significant predictor of change, but not in a consistent direction Prior CWS history is a predictor of change for both social and language skills Could be that they receive greater level of intervention, this time Could be that prior involvement already raised the level of their care or treatment (Barth, 2005) 42 Summary: Age 6-10 Only age group that showed improvements, although slight, in all developmental measures examined Only age group where age is not a significant predictor of rate of change for any domain Maltreatment type is the only significant predictor across more than one domain, yet with varied results (Barth, 2005) 43 National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being (NSCAW) • Adolescents deteriorated while in foster care on standard measures of well being. 44 Implications Children who became involved with child welfare services do not show marked gains in development during the first 18-months The youngest children show declines on developmental measures Out-of-home care does not appear to offer protection leading to improvement in developmental status over 18 months as might be expected Yet, among the older children, those with prior CWS involvement did better (Barth, 2005) 45 Implications CWS may be focusing on the more explicit goals of safety and permanency than on well-being, which appears to be beyond its current scope Revisions to CAPTA that require referrals of substantiated infant cases to early intervention seem very timely and need rapid implementation Specialized infant units may also be valuable Reductions in infant placements my help (Barth, 2005) 46 The growth in kinship care has been described by one scholar as the most significant change in foster care services over the past two decades. In Washington State, the kinship care rate has increased from around 26% to 40% of children in out-of-home care. 47 Kinship care is more stable than foster care. 48 However, an analysis of NSCAW data (n=567) by Barth, Guo, Green, and McCrae (2007) found that children in non-kin foster care were more behaviorally troubled at baseline than children placed with relatives. These authors state that “differences between children in kinship and non-kinship care… may simply reflect these pre-existing differences…” 49 In this same NSCAW analysis, children in kinship care improved more on the CBCL after 18 months in care than children in non-kin care; but on other developmental measures (e.g., Vineland, Social Skills Rating System), there were no significant differences in improvement / lack of improvement at 18 months after entry into care. 50 One of the most concerning findings in this study is that “about one-fifth of the children were rated as experiencing both low responsiveness and high punitiveness at both baseline an at 18 months,” a statistic that did not differ for kin and non-kin caregivers. “Low responsiveness” and “high punitiveness” is another way of describing harsh emotionally unresponsive parenting. 51 This study also found that one-fifth of foster parents (kin and non-kin) were poor, and that only 42% of non-kin foster parents had more than a high school degree. “Any general notion that foster parents are predominantly middle-class is untrue,” these authors state. 52 Acute and chronic placement shortages are having a large negative effect on the quality of foster care in Washington State and nationally. 53 Foster care systems experiencing acute and chronic shortages of homes cannot: Match children’s needs to foster family strengths and capacities Keep siblings together, especially sibling groups of larger than 2 children Place children in their own neighborhoods / communities Maintain high standards of care 54 Foster home recruitment initiatives over the past 10 years have not been effective despite a large investment of resources; and, as a result, the Children’s Administration has placed an increased emphasis on kinship care. 55 New strategies must be found to recruit and retain foster homes, or the number of children entering out-of-home care must be greatly reduced. 56 Possible strategies: Neighborhood- / community-based recruitment campaigns Professional foster care Better support / a larger percentage of the foster care system run by private agencies 57 It is also useful to have some humility about our collective understanding of the needs of children. What do these items have in common? Indenture Almshouses Orphanages Orphan Trains / Foster care Mother’s Pensions Therapeutic Foster Care Kinship Care / Family Group Conferencing Juvenile Institutions Residential Care Wrap Around / Community Placement All of the items on this list were child welfare reforms at one point. 58 Nevertheless, the need for non-kin foster care is not likely to greatly diminish without dramatic reductions in the child poverty rate and/or major improvements in child welfare in-home services for parents with co-occurring substance abuse and mental health disorders. 59 Barth and his colleagues have written that “a vision for excellence in foster care is needed.” These experts recommend increasing financial support for foster parents, “linking every foster parent to a resource center” or resource person, and providing “consistent, powerful, supportive in-home training.” 60 It is difficult to understand how foster care can become a therapeutic system for behaviorallytroubled children without developing a cadre of professional foster parents and implementing evidence-based practice models. 61 Bibliography Barber, J. G., & Delfabbro, P. H. (2006). Psychosocial well-being and placement stability in foster care: Implications for policy and practice. In R. F. Flynn, P. M. Dudding, & J. G. Barber (Eds.), Promoting resilience in child welfare (pp. 157-172). Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press. Barth, R. P. (2005, May 19). National Survey of Child and Adolescent WellBeing (NSCAW): How Are the Children Faring and Did Mental Health Services Help? Presented at the University of Washington School of Social Work. Barth, R. P., Guo, S., Green, R. L., & McCrae, J.S. (2007). Kinship care and nonkinship foster care: Informing the new debate. In R. Haskins, Wulczyn, F., & Webb, M. B. (Eds.), Child protection: Using research to improve policy and practice (pp. 187-206). Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press. 62 Bibliography Bellamy, J. L. (2008). Behavioral problems following reunification of children in long-term foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 30, 216-228. Doyle, J. J. (2007). Child protection and child outcomes: Measuring the effects of foster care. The American Economic Review, 97, 1583-1610. Flynn, R. J., Robitaille, A., & Ghazal, H. (2006). Placement satisfaction of young people living in foster or group homes. In R. F. Flynn, P. M. Dudding, & J. G. Barber (Eds.), Promoting resilience in child welfare (pp. 191-205). Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press. Landsverk, J., Davis, I., Ganger, W., Newton, R., & Johnson, I. (1996). Impact of child psychosocial functioning on reunification from out-of-home placement. Children and Youth Services Review, 18, 447-462. 63 Bibliography Lawrence, C. R., Carlson, E. A., & Egeland, B. (2006). The impact of foster care on development. Development and Psychopathology, 18, 57-76. Rubin, D. M., O’Reilly, A. L. R., Haffner, L., Luan, X., & Localio, A. R. (2007). Placement stability and early behavioral outcomes among children in outof-home care. In R. Haskins, Wulczyn, F., & Webb, M. B. (Eds.), Child protection: Using research to improve policy and practice (pp. 171-186). Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press. Rubin, D. M., O’Reilly, A. L. R., Luan, X., & Localio, A. R. (2007). The impact of placement stability on behavioral well-being for children in foster care. Pediatrics, 119, 336-344. Ryan, J. P., & Testa, M. F. (2005). Child maltreatment and juvenile delinquency: Investigating the role of placement and placement instability. Children and Youth Services Review, 27, 227-249. 64 Bibliography Shlonsky, A. R. & Berrick, J. D. (2001). Assessing and promoting quality in kin and nonkin foster care. Social Service Review, 75, 60-83. Taussig, H. N., Clyman, R. B., & Lansverk, J. (2001). Children who return home from foster care: A 6-year prospective study of behavioral health outcomes in adolescence. Pediatrics, 108: e10. Retrieved March 10, 2008, from http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/reprint/108/1/e10 Tarren-Sweeney, M. (2008). Retrospective and concurrent predictors of the mental health of children in care. Children and Youth Services Review, 30, 1-25. Wilson, L., & Conroy, J. (1999). Satisfaction of children in out-of-home care. Child Welfare, 78, 53-69. 65