File - kendra Langreck Portfolio

advertisement

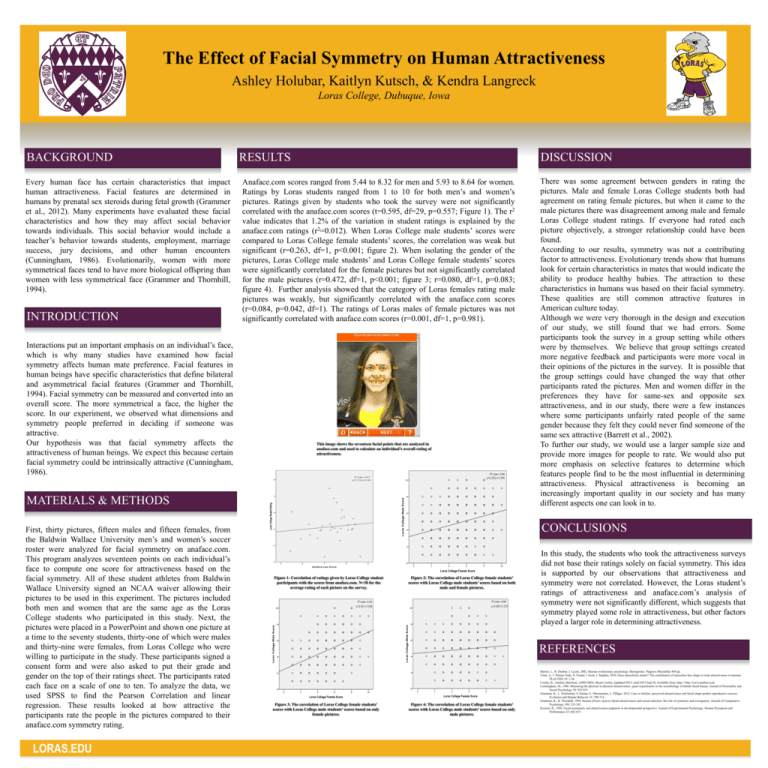

The Effect of Facial Symmetry on Human Attractiveness Ashley Holubar, Kaitlyn Kutsch, & Kendra Langreck Loras College, Dubuque, Iowa BACKGROUND Every human face has certain characteristics that impact human attractiveness. Facial features are determined in humans by prenatal sex steroids during fetal growth (Grammer et al., 2012). Many experiments have evaluated these facial characteristics and how they may affect social behavior towards individuals. This social behavior would include a teacher’s behavior towards students, employment, marriage success, jury decisions, and other human encounters (Cunningham, 1986). Evolutionarily, women with more symmetrical faces tend to have more biological offspring than women with less symmetrical face (Grammer and Thornhill, 1994). INTRODUCTION Interactions put an important emphasis on an individual’s face, which is why many studies have examined how facial symmetry affects human mate preference. Facial features in human beings have specific characteristics that define bilateral and asymmetrical facial features (Grammer and Thornhill, 1994). Facial symmetry can be measured and converted into an overall score. The more symmetrical a face, the higher the score. In our experiment, we observed what dimensions and symmetry people preferred in deciding if someone was attractive. Our hypothesis was that facial symmetry affects the attractiveness of human beings. We expect this because certain facial symmetry could be intrinsically attractive (Cunningham, 1986). RESULTS DISCUSSION Anaface.com scores ranged from 5.44 to 8.32 for men and 5.93 to 8.64 for women. Ratings by Loras students ranged from 1 to 10 for both men’s and women’s pictures. Ratings given by students who took the survey were not significantly correlated with the anaface.com scores (t=0.595, df=29, p=0.557; Figure 1). The r2 value indicates that 1.2% of the variation in student ratings is explained by the anaface.com ratings (r2=0.012). When Loras College male students’ scores were compared to Loras College female students’ scores, the correlation was weak but significant (r=0.263, df=1, p<0.001; figure 2). When isolating the gender of the pictures, Loras College male students’ and Loras College female students’ scores were significantly correlated for the female pictures but not significantly correlated for the male pictures (r=0.472, df=1, p<0.001; figure 3; r=0.080, df=1, p=0.083; figure 4). Further analysis showed that the category of Loras females rating male pictures was weakly, but significantly correlated with the anaface.com scores (r=0.084, p=0.042, df=1). The ratings of Loras males of female pictures was not significantly correlated with anaface.com scores (r=0.001, df=1, p=0.981). This image shows the seventeen facial points that are analyzed in anaface.com and used to calculate an individual’s overall rating of attractiveness. MATERIALS & METHODS First, thirty pictures, fifteen males and fifteen females, from the Baldwin Wallace University men’s and women’s soccer roster were analyzed for facial symmetry on anaface.com. This program analyzes seventeen points on each individual’s face to compute one score for attractiveness based on the facial symmetry. All of these student athletes from Baldwin Wallace University signed an NCAA waiver allowing their pictures to be used in this experiment. The pictures included both men and women that are the same age as the Loras College students who participated in this study. Next, the pictures were placed in a PowerPoint and shown one picture at a time to the seventy students, thirty-one of which were males and thirty-nine were females, from Loras College who were willing to participate in the study. These participants signed a consent form and were also asked to put their grade and gender on the top of their ratings sheet. The participants rated each face on a scale of one to ten. To analyze the data, we used SPSS to find the Pearson Correlation and linear regression. These results looked at how attractive the participants rate the people in the pictures compared to their anaface.com symmetry rating. LORAS.EDU There was some agreement between genders in rating the pictures. Male and female Loras College students both had agreement on rating female pictures, but when it came to the male pictures there was disagreement among male and female Loras College student ratings. If everyone had rated each picture objectively, a stronger relationship could have been found. According to our results, symmetry was not a contributing factor to attractiveness. Evolutionary trends show that humans look for certain characteristics in mates that would indicate the ability to produce healthy babies. The attraction to these characteristics in humans was based on their facial symmetry. These qualities are still common attractive features in American culture today. Although we were very thorough in the design and execution of our study, we still found that we had errors. Some participants took the survey in a group setting while others were by themselves. We believe that group settings created more negative feedback and participants were more vocal in their opinions of the pictures in the survey. It is possible that the group settings could have changed the way that other participants rated the pictures. Men and women differ in the preferences they have for same-sex and opposite sex attractiveness, and in our study, there were a few instances where some participants unfairly rated people of the same gender because they felt they could never find someone of the same sex attractive (Barrett et al., 2002). To further our study, we would use a larger sample size and provide more images for people to rate. We would also put more emphasis on selective features to determine which features people find to be the most influential in determining attractiveness. Physical attractiveness is becoming an increasingly important quality in our society and has many different aspects one can look in to. CONCLUSIONS Figure 1- Correlation of ratings given by Loras College student participants with the scores from anaface.com. N=30 for the average rating of each picture on the survey. Figure 2: The correlation of Loras College female students’ scores with Loras College male students’ scores based on both male and female pictures. In this study, the students who took the attractiveness surveys did not base their ratings solely on facial symmetry. This idea is supported by our observations that attractiveness and symmetry were not correlated. However, the Loras student’s ratings of attractiveness and anaface.com’s analysis of symmetry were not significantly different, which suggests that symmetry played some role in attractiveness, but other factors played a larger role in determining attractiveness. REFERENCES Figure 3: The correlation of Loras College female students’ scores with Loras College male students’ scores based on only female pictures. Figure 4: The correlation of Loras College female students’ scores with Loras College male students’ scores based on only male pictures. Barrett, L., R. Dunbar, J. Lycett, 2002. Human evolutionary psychology. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan 448 pp. Clark, A., I. Penton-Voak, N. Pound, I. Scott, I. Stephen, 2010. Does masculinity matter? The contribution of masculine face shape to male attractiveness in humans. PLoS ONE 10: 1-26. Cooley, B., Anaface [Internet]. c2009 (MO): Bryan Cooley; [updated 2012; cited 2013 Sept 9]. Available from: http:// http://www.anaface.com Cunningham, M., 1986. Measuring the physical in physical attractiveness: quasi-experiments on the sociobiology of female facial beauty. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 50: 925-935. Grammer, K., I. Holzleitner, S. Katina, E. Oberzaucher, L. Pflüger, 2012. Cues to fertility: perceived attractiveness and facial shape predict reproductive success. Evolution and Human Behavior 33: 708-714. Grammer, K., R. Thornhill, 1994. Human (Homo sapiens) facial attractiveness and sexual selection: the role of symmetry and averageness. Journal of Comparative Psychology 108: 233-242. Kowner, R., 1996. Facial asymmetry and attractiveness judgment in developmental perspective. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance 22: 662-675.