Economics 232 Industry and Government

advertisement

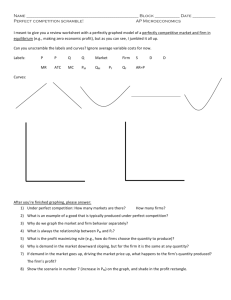

Economics 267 Industry and Government Summer 2003 Tu-Th 9:00-12:15 Castleman 201 R. N. Langlois Langlois@UConnVM.UConn.edu http://vm.uconn.edu/~langlois Office: Room 322 Monteith Office hours by appointment Points to remember. Come to class. Check online syllabus regularly for new links and materials. 2 Competition. What is competition? Why is it good? 3 Two views of competition. Competition as a process. Meaning of ordinary language. Competition as active striving, rivalry. Competition as a state of affairs. Formal, technical view. Lack of power over price. P f(Q) 4 The competitive spectrum Oligopoly Monopoly Atomism ? Only one seller, who is effectively insulated from competition. A handful of sellers, each one able to affect price but affected in turn by the behavior of competitors. Many sellers, each one too small to affect market price. 5 Perfect competition. Large number of “small” buyers and sellers. None large enough to affect market price. “Atomism.” Homogeneous product. Each product a perfect substitute for all others. A subjective, not objective, criterion. (Eyes of the buyer.) 6 Perfect competition. Productive resources freely mobile. Free entry and exit. No “barriers to entry.” Perfect knowledge. Everyone knows all buyers and sellers. Everyone uses best practice technology. Implies all firms identical. 7 Analysis of perfect competition. MC $/q Perfect competitor is a “price taker.” AC P1 d1 Faces a perfectly horizontal demand curve. . Chooses quantity q* so that MR = MC. q* q/t For perfect competitor, P = MR. If P > AC at q*, firm makes a profit. Π = (P1 – AC)q* In the short run, when no new firms can enter. An economic profit. Marshall: quasi-rents. 8 Analysis of perfect competition. MC $/q S1 D d1 . S2 $/q AC P1 MC q/t AC P1 P2 q* $/q P2 Q1 Q2 q/t d2 q* q/t In the long run, profit attracts entry. Addition of new firms shifts out market supply curve. Entry continues until price is bid down to minimum point of individual firm’s AC curve. Price of output now exactly equal to the opportunity cost of resources used in production. 9 Competition as a process. Older view – before Adam Smith Competition as striving, rivalry. Firms can compete at any size. Firms can compete by changing the product. Adam Smith (17231790). Author of the Wealth of Nations (1776). Picture courtesy of the Warren J. Samuels Portrait Collection at Duke University. Knowledge never perfect. Knowledge a result of -- not a requisite to -- competition. Competition as a discovery procedure. Free entry still essential. F. A. Hayek (1899-1992) 10 A comparison. Structure Perfect competition Process competition Atomism is a desirable goal. Any market structure can be competitive. 11 A comparison. Product differentiation Perfect competition Undesirable Process competition May be a form of competition. 12 A comparison. Contractual practices Perfect competition Typically undesirable. Evidence of “market power.” Process competition May be evidence of competition or requisites to competition. 13 A comparison. Free entry Perfect competition Process competition Necessary. Necessary. 14 A comparison. Knowledge Perfect competition Process competition Should be “perfect.” Diversity of knowledge can create “market power.” Competition as generating knowledge. Dispersion of knowledge desirable. 15 Monopoly. Two systems of belief about monopoly. Interventionist monopoly. Competition tends to eliminate market power unless there are government barriers. True monopoly is a creature of the state. Spontaneous monopoly. “Natural tendency” for monopolies to arise and persist. Need for active antitrust policy. 16 Analysis of monopoly. $/Q Firm’s demand curve is the market demand curve. MR falls faster than demand. Why? Suppose monopolist lowers price. Loss in revenue from lowering price to existing (inframarginal) customers. P1 P2 Gain in revenue from attracting new customers. D=AR Q1 Q2 No price discrimination. Q/t 17 Analysis of monopoly. $/Q Monopolist chooses Qm so that MR = MC. Demand curve determines monopoly price Pm. Not true that a monopolist can set “any price it wants.” Pm MC=AC A monopolist operates on the elastic part of the demand curve. D=AR Qm Q/t MR 18 What’s wrong with monopoly? $/Q A perfectly competitive industry would choose Qc where D = MC. Economic profit would be zero. Shaded area is consumers’ surplus. MC=AC Pc D=AR Qc Consumer’s surplus is the difference between what the consumer is willing to pay and what he or she has to pay. Q/t 19 What’s wrong with monopoly? $/Q CS Pm Monopoly restricts output and raises price relative to the competitive benchmark. Some consumers’ surplus becomes producer’s surplus (profit). Is this what is wrong with monopoly? PS MC=AC Pc Transfers of surplus can be regressive or progressive. D=AR Qm Qc Q/t MR 20 What’s wrong with monopoly? $/Q CS Pm Monopoly restricts output and raises price relative to the competitive benchmark. As a result, some potentially beneficial gains from trade don’t take place. Total surplus is diminished by the extent of the deadweight-loss triangle. PS DWL MC=AC Pc Total (social) surplus is CS + PS. D=AR Qm Qc Q/t MR 21 Pareto efficiency. A minimalist criterion of efficiency. Vilfredo Pareto (1848-1923) A change is Pareto improving if it leaves at least one person better off and no one worse off. 22 Pareto efficiency. An allocation is not Pareto efficient if … 23 Pareto efficiency. There is any left on the table. Could make one better off without making the other worse off. 24 What’s wrong with monopoly? $/Q Monopoly is not Pareto efficient. CS Why? Pm Let’s make a deal. PS DWL MC=AC Pc D=AR Qm Qc Q/t MR 25 What’s wrong with monopoly? A $/Q Consumers ask monopolist to produce at the competitive level Qc. Consumers’s surplus expands to APcB. Pm B Pc MC=AC D=AR Qm Qc Q/t MR 26 What’s wrong with monopoly? $/Q In exchange, consumers “bribe” the monopolist by transferring back: all producer’s surplus, plus (say) half of the DWL. Pm Now both are better off. MC=AC Pc Ah, but transaction costs! D=AR Qm Qc Q/t MR 27 The competitive spectrum Oligopoly Monopoly Atomism ? Only one can affect price. Behavior not constrained, but only one “rational” result. Price and quantity depend on interaction among firms. Expectations matter. No one can affect price. Behavior perfectly predictable. 28 The prisoners’ dilemma. Two suspects – Smith and McAlpin – apprehended for bank robbery. Police have little evidence, so they arrest them on lesser charges and attempt to get confessions. Suspects taken into separate interrogation rooms and offered plea-bargain deals. 29 The prisoners’ dilemma. McAlpin Don’t Confess Smith Confess Don’t Confess -1, -1 -10, 0 Confess 0, -10 -6, -6 Difficulty of coordination. Difficulty of commitment. 30 Oligopoly pricing. Firm B PB = $130 PA = $130 Firm A PA = $105 PB = $105 Joint profit maximization. 111, 111 57, 122 Incentive to cheat on cartel. 122, 57 Nash equilibrium. 95, 95 31 The Cournot model. Nash equilibrium: “A set of strategies is called a Nash equilibrium if, holding the strategies of all other firms constant, no firm can obtain a higher payoff (profit) by choosing a different strategy. Thus, in a Nash equilibrium, no firm wants to change its strategy.” (Carlton & Perloff, p. 157.) John F. Nash, Jr (1928-) Cournot model. Firms compete by choosing quantity. Firms can’t coordinate or commit. Firms calculate optimal response to all possible moves by opponents. Cournot-Nash equilibrium. Antoine Augustin Cournot (1801-1877) 32 The Cournot model. The Lerner index of market power. Abba P. Lerner (1903-1982) P - MC L= P L = 0 is socially optimal – no market power. Cournot model with n identical firms. 1 L= nε ε is elasticity of demand. Antoine Augustin Cournot (1801-1877) L 0 as n . Market power a smooth declining function of number of firms. Market concentration equals market power. 33 Oligopoly pricing. How secure is the relationship between concentration and market power? π2 Profit possibilities frontier On the frontier means joint-monopoly pricing. Cournot Assumptions are everything. Stackelberg Bertrand At the origin means efficient pricing. π1 Carlton & Perloff (1999, p. 164). 34 Oligopoly behavior. The Harvard School Structure largely determines market power. “Tacit” collusion. Edward H. Chamberlin, 1899-1967 Unexamined assumptions about expectations and transaction costs. 35 Oligopoly behavior. The Chicago School Incentive to cheat on cartel. Collusion isn’t free. Costs of coordinating. Costs of policing. George J. Stigler, 1911-1991. Using transaction-cost reasoning to address the problem of interdependence. 36 Oligopoly behavior. Secret price cutting most likely when: Number of sellers high. Products heterogeneous. Large differences in costs. Orders lumpy and infrequent. Price information is secret. Role of trade associations. Elbert H. Gary (1846-1927), founder of U. S. Steel and convener of the famous “Judge Gary dinners” at which Steel industry competitors set production quotas and collusive prices. “Social structure” not conducive to collusion. 37 Appraising oligopoly. Why do we like perfect competition? William Stanley Jevons, 1835-1882 "The problem of economics may, as it seems to me, be stated thus: -- Given, a certain population, with various needs and powers of production, in possession of certain lands and other sources of material: required, the mode of employing their labour which will maximize the utility of the produce." (Theory of Political Economy, 4th ed., p. 267.) The last unit of output is earning exactly the opportunity cost of the resources that went into it. Static resource allocation. But is that all we might ask for in appraising industry structure? 38 Appraising oligopoly. Two themes. Is the setting of optimal price and quantity the only economic problem firms are trying to solve? The “inhospitability tradition.” Example: Can collusion in highthroughput industries (like steel) also lower costs by reducing uncertainty? Is static efficiency the right (or the only) criterion of efficiency? 39 Appraising oligopoly. Economic growth: Secular increase in output. Lower prices. Creation of new products. Development of new technologies. Is there a conflict between the goal of static resource allocation and the goal of economic growth? 40 Schumpeterian competition. Joseph A. Schumpeter (1883-1950), author of Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy (1942) “As soon as we go into details and inquire into the individual items in which progress was most conspicuous, the trail leads not to the doors of those firms that work under conditions of comparatively [atomistic] competition but precisely to the doors of the large concerns — which, as in the case of agricultural machinery, also account for much of the progress in the competitive sector — and a shocking suspicion dawns upon us that big business may have had more to do with creating [the modern] standard of life than with keeping it down” (p. 82). 41 Schumpeterian competition. Creative destruction. “[T]he problem that is usually being visualized is how capitalism administers existing structures, whereas the relevant problem is how it creates and destroys them” (p. 84) Joseph A. Schumpeter (1883-1950), author of Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy (1942) “… competition from the new commodity, the new technology, the new source of supply, the new type of organization (the largestscale unit of control for instance) — competition which commands a decisive cost or quality advantage and which strikes not at the margins of the profits and the outputs of the existing firms but at their foundations and their very lives. This kind of competition is as much more effective than the other as a bombardment is in comparison with forcing a door, and so much more important that it becomes a matter of comparative indifference whether competition in the ordinary sense functions more or less promptly; the powerful lever that in the long run expands output and brings down prices is in any case made of other stuff” (pp. 84-85). 42 Schumpeterian competition. The “Schumpeterian hypothesis.” Joseph A. Schumpeter (1883-1950), author of Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy (1942) Do big firms (or firms with market power?) innovate more than small firms? A relatively confused and arid debate. Empirical evidence: oligopolies are more innovative than either perfect competitors or monopolists. Do firms innovate well because they are big – or do they get big because they innovate well? 43 Barriers to entry. Monopoly model and Cournot model both assume no threat of entry. But economic profits are a lure to potential entrants. Barriers to entry. What are they? 44 Barriers to entry. Bain. Joe S. Bain, 1912- Barriers to entry: “the extent to which, in the long run, established firms can elevate their selling prices above the minimal average costs of production and distribution … without attracting potential entrants to enter the industry.” (Industrial Organization. New York: Wiley, 1968, p. 252). 45 Barriers to entry. Bain. Examples: High capital costs. Large advertising expenditures. Everything but the kitchen sink. Joe S. Bain, 191246 Relative cost advantages. Can factors like capital costs or advertising expenditures be barriers just because they are high? Assume all firms have identical costs but that average costs are declining. 47 Relative cost advantages. Deterring small-scale entry But what deters large-scale entry? $ D Incumbent can set a limit price PL to deter entry at any scale less than MES. AC PL QE MES Q/t 48 Relative cost advantages. Entry is not always, or even usually, about small entrants challenging large incumbents. Entry of large-scale competitors with complementary assets. Example: Bowmar Brain. Entry from a different technological base. Example: locomotives. 49 Strategic entry deterrence. Can an incumbent use strategy to deter large-scale entry? Remember: we are assuming firms have identical costs. Sylos postulate: Incumbent firms threaten to maintain their output in the face of entry. Entrants left with “residual” demand curve. 50 Strategic entry deterrence. Incumbent(s) choose a limit price PI that ensures that the entrant can do no better than break even. So, is the shape of the cost curve a barrier to entry? $ Remember that entrant has same cost curve as incumbent. D AC PI PE QE QI Residual demand Q/t 51 Strategic entry deterrence. (πM, 0) Stay out Entrant Fight Enter πM > πS > 0 > πW (πW, πW) Incumbent Share (πS, πS) A potential entrant who believes the threat to maintain output will be deterred. But the Sylos postulate is not a credible threat, since incumbent has no incentive to carry it out once entry has occurred. πS > π W 52 Strategic entry deterrence. Credible commitments. To make a threat credible, a player must make an irreversible commitment that changes his or her incentives or constrains his or her action. Thomas C. Schelling, 1921- Ulysses and the Sirens. The Doomsday Device. Ulysses and the Sirens by John William Waterhouse (British, 1849-1917), National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia. Peter Sellers in Dr. Strangelove (1964). 53 Strategic entry deterrence. (πM-C, 0) Stay out Entrant Fight Enter (πW, πW) Incumbent Share (πS-C, πS) Incumbent invests C (a sunk cost) in (for example) excess production capacity useful only in the event of a price war. The threat is now credible if πW > πS-C. The threat is worth making if πM-C > πS. So choose C so that πM- πS > C > πS- πW. 54 Strategic entry deterrence. (πM-C, 0) Stay out Entrant Fight Enter (πW, πW) Incumbent Share (πS-C, πS) Does this mean that strategic commitments save the Bain-Sylos account of barriers to entry? Notice that, because of the commitment, the incumbent no longer has the same costs as the entrant. 55 Absolute cost advantages. Stigler. “A barrier to entry may be defined as a cost of producing (at some or every rate of output) which must be borne by a firm which seeks to enter an industry but is not borne by firms already in the industry.” (The Organization of Industry. Homewood, Ill.: R. D. Irwin, 1968, p. 67.) George J. Stigler, 1911-1991. 56 Absolute cost advantages. Stigler. Examples: High capital costs are not a barrier unless the incumbent didn’t also have to pay them. Capital market “imperfections.” George J. Stigler, 1911-1991. Ditto large advertising expenditures. 57 Absolute cost advantages. $ ACE ACI Not all absolute cost barriers are policy relevant. A barrier is policy relevant if removing the barrier will improve economic efficiency. Example: Superior knowledge or technology. Q/t 58 Raising rivals’ costs. Investing resources to create cost advantages. It may pay to raise rivals’ costs even if it means raising your own. Example: the strategic use of regulation. Margarine and whiskey. 59 Barriers and property rights. Are there barriers All cabs must hold a taxi to entry in the medallion. New York taxicab Limited by law to 12,187. business? But incumbents do not have a cost advantage. Insider-outsider distinction fails to identify a barrier. 60 Barriers and property rights. Average Annual Medallion Prices 1947, 1950, 1952, 1959, 1960 and annually since 1962. Source: Schaller Consulting. 61 Barriers and property rights. Demsetz. Barriers to entry ultimately reduce to rights over assets. Do the benefits of the barrier (right) outweigh the costs? Rights (barriers) solve problems of externality. Harold Demsetz, 1930- Ordinary property rights. Taxi medallions? Transferable pollution quotas. 62 Barriers and property rights. M $ S' Maker of widgets doesn’t have to pay full cost of production. S An externality. Example: pollution. S is “apparent” supply curve. S' is “true” supply curve. P' P D (demand for widgets). Pollution quota limits output by restricting a scarce input. Q' Q Q/t Industry produces “too many” widgets. 63 Barriers and property rights. M $ S' S P' Original owners of pollution rights receive a scarcity rent. Rent is capitalized into the value of the rights when they are exchanged. P D (demand for widgets). Q' Q Q/t 64 Scarcity rents. David Ricardo (1772-1823) Image courtesy of the Warren J. Samuels Portrait Collection at Duke University. Economic rent. Payments made to a factor that are in excess of what is required to elicit the supply of that factor. • Greater than the opportunity cost. Alfred Marshall (1842-1924) Quasirents. Payments made to a factor that are in excess of what is required to elicit the supply of that factor in the short run. • Can be bid away in the long run. 65 Scarcity rents. $/Q Scarcity rents or monopoly power? Assume: D MR All factors used in fixed proportions. All but one factor available in perfectly elastic supply (CRTS). One factor constrained. Q/t This analysis follows Winter (1995, pp. 159-167). 66 Scarcity rents. $/Q Rent goes to the factor owner. PA C MR QA This analysis follows Winter (1995, pp. 159-167). Constrained input limits the production of output. Price is above cost, but firm has no incentive to restrict output. (PA – C)QA is a scarcity rent. If the firm owns all of the constrained factor, it D keeps the rent. If the firm has to buy the factor on a competitive Q/t market, it bids the factor price up to (PA – C). 67 Scarcity rents. $/Q The difference between the profit and the scarcity rent is the monopoly rent. PA PB PD C Suppose now that the input suffices to produce QD. A competitive industry would set price PD and scarce factor would earn rent (PD – C)QD . But a firm that controls all the factor would also want to restrict output to QB . D MR QA QB QD This analysis follows Winter (1995, pp. 159-167). Q/t There is now deadweight loss. The firm’s profit is now (PB – C)QB . 68 Scarcity rents. Distinctive knowledge as a scarce factor. Kinds of knowledge inputs. Explicit knowledge as a public good. Tacit and poorly understood routines. May also be linked to specific asset or site. Can the innovator replicate the input? Can competitors imitate the input? Patents and secrecy. Complexity and ambiguity. 69 Scarcity rents. Efficiency-enhancing innovation Replicable by innovator? NO YES Incentive to restrict output? NO Scarcity (Ricardian) rents YES Imitable? NO Scarcity rents + monopoly rents This analysis follows Winter (1995, pp. 159-167). YES Quasirents or Schumpeterian rents 70 Barriers to entry. Conclusion: Barriers to entry always reduce to property rights over a scarce factor. Efficiency or inefficiency of a barrier depends on: Costs/benefits of exclusion. Demand and cost conditions. 71 Intellectual property rights. Patent. Origins in medieval and early modern royal grants. Letters patent vs. letters close. Copyright. Letters patent of Queen Elizabeth II, 1964 Protects artistic expression. Trademark. Encourages investment in reputational capital. 72 The economics of patents. The invention-motivation theory of patents. Firm expends resources on R&D to create a new product. Expenditures are a sunk cost equal (in flow terms) to IJKL. I J L K 73 The economics of patents. $/Q A Successful innovation creates a new demand curve. CS B This generates total social surplus PcAC. Pm PS DWL C Pc MC D D=AR Qm Qc Q/t MR 74 The economics of patents. $/Q A A patent confers monopoly power for 17 years. CS I J L K B Pm PS DWL C Pc MC D D=AR Qm Qc Q/t An ideal patent would exactly compensate the firm for sunk costs of R&D. PcPmBD = IJKL. MR 75 The economics of patents. $/Q A Consumers still benefit by PmAB. CS I J L K B Pm PS DWL C Pc MC D D=AR Qm Qc But DWL (area DBC) is the price of creating an incentive to innovate. Q/t MR 76 The economics of patents. $/Q A Without a patent, competitors would bid price down to Pc CS I ? L Pc C Qc J K Consumers (society) would MC benefit in principle, but firms would have no incentive to D=AR expend resources on Q/t innovation. 77 Intellectual property rights. Issues: A letters patent of Queen Elizabeth II, 1964 Other mechanisms for appropriating the returns to innovation. Is research seeking the same idea or many diverse ideas? Differences in technology and in the process of technical advance. 78 Appropriation mechanisms. Tacit knowledge. Trade secrets. First-mover advantages. Complementary assets. 79 Patent races. Invention-motivation theory assumes inventors are not competing for the same ideas. Patent races and overfishing models. Generating “too much” research effort. But how frequent are patent races? James Watson and Francis Crick with a model of DNA 80 Topography of technological advance. Science-based industries. Cumulative systems industries. 81 Topography of technological advance. Science-based industries. Discovery of a single explicit “idea.” Knowledge is “slippery.” Invention-motivation theory works reasonably well. Example: pharmaceutical patents and the price of drugs. 82 Topography of technological advance. Cumulative systems industries. Technical advance depends on small improvements in an interconnected system. Knowledge is tacit. Examples: automobiles, radio, airframes. 83 Intellectual property rights. Patent scope. A letters patent of Queen Elizabeth II, 1964 General ideas vs. specific processes. Example: the Selden patent. Blocking patents. The “anticommons.” Patent pools. 84 Advertising. Information or persuasion? Assumptions about the nature and role of knowledge. World 1: knowledge free and perfect. World 2: information costly. World 3: open-ended possibilities. 85 World 1. If knowledge is free and perfect, advertising can have no informational role. Assumptions of perfect competition. The only role left for advertising is to influence preferences. 86 World 1. In this world, advertising is persuasion: it increases consumer demand. $ Does advertising create brand loyalty? Is advertising a barrier to entry? P' P D' D Q Q/t 87 World 1. $ P Alternatively, advertising might decrease demand elasticity. D Increases market power of firms. Makes industry less competitive? D' Q/t 88 World 2. $/hour Information is costly. Consumers know which products exist, but it is costly to find (say) the MCs lowest price. Advertising reduces search costs. MBs' MBs S' S Search time (hours) 89 World 2. Benham: the effect of advertising restrictions on prices. States varied in restrictions on the advertising of prescription eyeglasses (1963 and before). Prices in restrictive states higher by 25 to 100 per cent than in laissez-faire states. NC: $37.48; Texas and DC: $17.98. 90 World 2. Brand loyalty more important when advertising is forbidden. States varied in restrictions on the advertising of prescription eyeglasses (1963 and before). Prices in restrictive states higher by 25 to 100 per cent than in laissez-faire states. NC: $37.48; Texas and DC: $17.98. 91 World 2. Advertising tends increase rather than decrease demand elasticity. States varied in restrictions on the advertising of prescription eyeglasses (1963 and before). Prices in restrictive states higher by 25 to 100 per cent than in laissez-faire states. NC: $37.48; Texas and DC: $17.98. 92 Truth in advertising. If advertising is truthful, does it ever reduce welfare? If advertising changes tastes, which set of tastes do we use to evaluate it? If information is costly, can advertising mislead consumers? 93 Truth in advertising. Three kinds of goods. Search goods. Experience goods. Credence goods. Actual goods may have characteristics of two or more types. 94 Truth in advertising. Search goods. Qualities can be determined prior to purchase. Consumer can cheaply verify the truth of claims about search characteristics. Size, ripeness, color, etc. Incentive to target ads to the right consumers. Misleading advertisement of search characteristics costly to advertiser. 95 Truth in advertising. Experience goods. Qualities can be determined only after purchase. Direct information about quality harder to verify (and thus less valuable to consumers). Non-specific claims of quality or no quality claims at all. Indirect information. Advertising as a signal. Advertising and reputational capital. 96 Truth in advertising. Credence goods. Qualities can’t be determined even after purchase. Medical care, car repair. Consumers uncertain about both amount and quality. Producers have scope to sell “too much” or cheat on quality. But this has little to do with advertising. Information costs and the “optimal amount of fraud.” 97 World 3. Do people have a complete list of all possible products in their heads? Advertising as competition for scarce attention. The medium is the message: value of advertising is the fact of advertising not the message. As number of products increase, will advertising have to yell louder? 98 Network effects. A network is a system of complementary nodes and links. See the Dictionary of Terms in Network Economics. 99 Network effects. Physical connection networks. Mark Twain had one of the first telephones in Hartford. “Virtual” networks. Hardware-software networks. 100 Network effects. Standards: The set of rules that assure compatibility between nodes and links in the network. The great Baltimore fire of 1904. 101 Network effects. Network effects: See the Dictionary of Terms in Network Economics. Membership in the network becomes more valuable in proportion to the number of other people who are already members (or who are expected to become members). 102 Path-dependence and “lock-in.” Paul A. David, 1935- A path-dependent sequence of economic changes is one of which important influences upon the eventual outcome can be exerted by temporally remote events, including happenings dominated by chance elements rather than systematic forces. (David 1985, p. 332). Example: the QWERTY keyboard. The Sholes & Glidden Type Writer (1874) 103 Path-dependence and “lock-in.” The story of QWERTY. Paul A. David, 1935- The Sholes & Glidden Type Writer (1874) Christopher Latham Sholes 1868. Remington produces first model 1874. The QWERTY layout: Marketing gimmick? Attempt to slow typing speed? Crucial typing contest in Cincinnati 1888. The invention of touch typing. A historical accident that QWERTY won? 104 Path-dependence and “lock-in.” Typing as a virtual network. Hardware: the keyboard layout. Paul A. David, 1935- The Sholes & Glidden Type Writer (1874) Software: touch-typing skills. Technological interrelatedness. High conversion costs. Positive feedback. “Tipping” to a dominant standard. 105 Path-dependence and “lock-in.” Are we “locked in” to an inefficient keyboard standard? Paul A. David, 1935- The Sholes & Glidden Type Writer (1874) The QWERTY keyboard. The Dvorak keyboard. 106 Path-dependence and “lock-in.” The choice of QWERTY not entirely historical accident. There were many competing typewriters. There were many typing contests like the one in Cincinnati. Liebowitz and Margolis criticize the QWERTY story. Dvorak is not greatly superior to QWERTY. The Navy study. The importance of rhythm. 107 Path-dependence and “lock-in.” Sensitivity to starting point. But no inefficiency. Examples: First degree path dependency. Liebowitz and Margolis (1995). Language. Side-of-the-road driving conventions. 108 Path-dependence and “lock-in.” Sensitivity to starting point. Imperfect information. Outcomes are regrettable ex post. But no inefficiency, in the sense that no better decision could have been made at the time. Second degree path dependency. Liebowitz and Margolis (1995). 109 Path-dependence and “lock-in.” Sensitivity to starting point. Inferior outcome. Inefficient, in the sense that the inferior outcome could have been avoided. Error is remediable. Third degree path dependency. Liebowitz and Margolis (1995). 110 Path-dependence and “lock-in.” Technology B is superior. Table from Arthur (1989). Produces highest value in the long term. But Technology A has higher short-term payoffs. Example: QWERTY stops mechanical keys from jamming. Conclusion: choice of – and lock-in to – wrong standard. 111 Path-dependence and “lock-in.” Table from Arthur (1989). But this result depends on imperfect information. If users could correctly forecast, they would adopt B. The real issue: which institutional structure will choose best under poor information? Do markets choose badly? 112 Path-dependence and “lock-in.” The role of a technology “champion.” Table from Arthur (1989). Someone who “owns” a system has an incentive to see it adopted. Champions who forecast higher long-term payoffs can subsidize adoption in the short term. MS-DOS versus Apple and other examples. Competing champions and local knowledge. 113 Standards as barriers. Types of Standards: Open versus closed. Some “semi-open.” Example: Windows Proprietary versus nonproprietary. Economics of networks predicts a single dominant standard, not necessarily a single monopoly owner. Privately proprietary (IBM 360). “Collectively” owned (fax standards). Unowned (stereo systems, Linux?) 114 Anatomy of a network product. Product 1 Product 2 Ease of use Ease of use Style Style Autarky value Durability Durability Maintenance costs Maintenance costs Compatibility Synchronization value 115 Standards as barriers. If someone “owns” a standard, he or she has a property right to a restricted input. The compatibility attribute. Microsoft and the “applications barrier to entry.” 116 Standards as barriers. Standards as “essential facilities.” U. S. v. Terminal Railroad Association (1912). Ski slopes and copier parts. Standards and “serial monopoly.” Schumpeterian competition. Is (temporary) monopoly necessary to encourage champions to subsidize valuable standards? 117 Crafts production. A1 A2 B1 C1 B2 B3 C2 A4 B4 C3 D1 E1 A3 E2 D2 D3 E3 A5 B5 C4 D4 E4 C5 D5 E5 Time 118 Crafts production. A1 A2 B1 C1 B2 B3 C2 A4 B4 C3 D1 E1 A3 E2 D2 D3 E3 Time A5 B5 C4 D4 E4 C5 D5 E5 Artisans work at their own pace. Differences in absolute and comparative skill across tasks. Ease of “systemic” change in product. Uniqueness of crafts-made goods. Need for “wide” human capital. Skilled artisan must master many different tasks. 119 Factory production. A1 B2 A1 C3 B2 A1 D4 C3 B2 A1 E5 D4 C3 B2 A1 E5 D4 C3 B2 E5 D4 C3 E5 D4 E5 Time 120 Factory production. A1 B2 A1 C3 B2 A1 D4 C3 B2 A1 D4 C3 B2 A1 Time Shift from parallel to series. E5 E5 D4 C3 B2 E5 D4 C3 E5 D4 E5 Time phasing of inputs. Workers work at pace of team. Workers complements not substitutes. Product standardized. Difficulty of systemic change. Ease of “autonomous” change and learning by doing. 121 Factory production. A1 B2 A1 C3 B2 A1 D4 C3 B2 A1 D4 C3 B2 A1 Time Physical capital saving. E5 E5 D4 C3 B2 E5 D4 C3 E5 D4 E5 Need only one set of tools. Economizes on work-in-process (buffer) inventories. Human capital saving. “Deskilling.” Workers sorted by comparative advantage. Human capital “deepening” instead of widening. 122 The division of labor. Improvement in “skill and dexterity.” Charles Babbage (1791-1871). Learning by doing. Spread fixed set-up costs. Less “sauntering” between tasks. Increased innovation. Operative focused on and benefits from “abridging labour.” Specializing in invention. Assign operatives according to comparative advantage. Adam Smith (1723-1790). Author of the Wealth of Nations (1776). Picture courtesy of the Warren J. Samuels Portrait Collection at Duke University. 123 The division of labor. Howe pin-making machine, about 1840. (Smithsonian Institution.) Adam Smith (1776): ten men could make 48,000 pins a day, or almost 5,000 per person per day. Karl Marx (1867): one woman or girl could supervise four machines, each making 145,000 pins per day, for almost 600,000 per person per day. Pratten (1980): one person could supervise 24 machines, each making 500 pins a minute, or about 6 million pins per person per day. 124 The problem of organization. A1 B2 C3 D4 E5 But the division of labor by itself doesn’t say anything about the boundaries of the firm. Are the stages of production each a separate firm, or are some stages within a single firm? Vertical integration. 125 The problem of organization. X1 X2 X3 black box Q The theory of the firm we’ve learned so far doesn’t help much. The firm as a black box. Boundaries of the firm assumed. 126 Why are there firms? The master gun-maker -- the entrepreneur -- seldom possessed a factory or workshop. ... Usually he owned merely a warehouse in the gun quarter, and his function was to acquire semifinished parts and to give those out to specialized craftsmen, who undertook the assembly and finishing of the gun. He purchased material from the barrel-makers, lockmakers, sight-stampers, trigger-makers, ramrod-forgers, gun-furniture makers, and, if he were engaged in the military branch, from bayonet-forgers. All of these were independent manufacturers executing the orders of several master gun-makers. ... Once the parts had been purchased from the "material-makers," as they were called, the next task was to hand them out to a long succession of "setters-up," each of whom performed a specific operation in connection with the assembly and finishing of the gun. To name only a few, there were those who prepared the front sight and lump end of the barrels; the jiggers, who attended to the breech end; the stockers, who let in the barrel and lock and shaped the stock; the barrel-strippers, who prepared the gun for rifling and proof; the hardeners, polishers, borers and riflers, engravers, browners, and finally the lock-freers, who adjusted the working parts. [G. C. Allen, The Industrial Development of Birmingham and the Black Country, 1906-1927. London, 1929, pp. 56-57.] 127 Why are there firms? “The main reason why it is profitable to establish a firm would seem to be that there is a cost of using the price mechanism.” Ronald H. Coase (1910-) Cost of discovering the relevant prices. Costs of negotiating and concluding a separate contract for each exchange. Not completely eliminated by intermediaries. Employment contract vs. spot contract. Costs of coordinating when tasks are uncertain. 128 The parable of the secretary. Why not pay for office services by the piece? $1 per letter typed, etc. Manager unlikely to know in advance which services needed. Manager pays for the secretary’s time, and decides tasks later. Contract for “job description.” 129 The size of the firm. A1 B2 C3 D4 E5 Ronald H. Coase (1910-) The size of the firm not its output (Q) but the number of transactions or activities within its boundaries. 130 The size of the firm. Why doesn’t the firm expand forever? V. I. Lenin: “The whole of society will have become one office and one factory.” But: diminishing returns to internal coordination. Management as a fixed factor. 131 The size of the firm. Ronald H. Coase (1910-) “A firm will tend to expand until the costs of organising an extra transaction within the firm become equal to the costs of carrying out the same transaction by means of an exchange on the open market or the costs of organising in another firm.” (Coase 1937, p. 395.) 132 The size of the firm. $ CPS + CAC Costs of administrative coordination. Costs of the price system. T* Size of the firm. Number of transactions (ordered from most to least costly to execute through the price mechanism). 133 The size of the firm. “It should be noted that most inventions will Ronald H. Coase (1910-) change both the costs of organising and the costs of using the price mechanism. In such cases, whether the invention tends to make firms larger or smaller will depend on the relative effect on these two sets of costs. For instance, if the telephone reduces the costs of using the price mechanism more than it reduces the costs of organising, then it will have the effect of reducing the size of the firm.” (Coase 1937, p. 397n.) 134 The nature of the firm. Armen Alchian (1919-) Harold Demsetz (1930-) But is a firm something different from a market? “Telling an employee to type this letter rather than to file that document is like my telling a grocer to sell me this brand of tuna rather than that brand of bread.” (Alchian and Demsetz 1972, p. 777.) The firm as a nexus of contracts. 135 Transaction costs. The “costs of using the price system” came to be called transaction costs. Ex ante transaction costs. Ronald H. Coase (1910-) The costs of finding trading partners, negotiating, coordinating. Ex post transaction costs. The costs of opportunism after the deal is made. Oliver E. Williamson (1932-) “Self-interest seeking with guile.” Asset specificity versus moral hazard. 136 Composite quasirent. Alfred Marshall (1842-1924) Indeed, in some cases and for some purposes, nearly the whole income of a business may be regarded as a quasi-rent, that is an income determined for the time by the state of the market for its wares, with but little reference to the cost of preparing for their work the various things and persons engaged in it. In other words it is a composite quasi-rent divisible among the different persons in the business by bargaining, supplemented by custom and by notions of fairness … Thus the head clerk in a business has an acquaintance with men and things, the use of which he could in some cases sell at a high price to rival firms. But in other cases it is of a kind to be of no value save to the business in which he already is; and then his departure would perhaps injure it by several times the value of his salary, while probably he could not get half that salary elsewhere. (Marshall 1961, VI.viii.35.) 137 Asset specificity. The “fundamental transformation.” Oliver E. Williamson (1932-) Incentives change once the contract is signed. One party may have an incentive to “hold up” the other. Transfer some of the quasirents of cooperation. 138 Asset specificity. One party owns a generic asset. High value outside of the transaction (next best use). The other party owns a highly specific asset. Low value outside the transaction. Next best use is as a boat anchor. Assume also that parties cannot recontract until “next season.” 139 Asset specificity. Cooperation nets $50,000. Oliver E. Williamson (1932-) Agree to split 50/50. Once the contract is signed, the party with the generic asset threatens to pull out of the contract. Demands $49,000 of the quasirents of cooperation. “Post contractual opportunism.” 140 Asset specificity. Foreseeing such “contractual hazards,” parties will be reluctant to cooperate. Or will choose less specialized but therefore less efficient technology. Vertical integration solves the hold-up problem. The two parties jointly own both assets. Incentives now properly aligned. 141 Asset specificity. Choice between markets and internal organization. Oliver E. Williamson (1932-) Markets promote high-powered incentives. Markets can aggregate demands and realize economies of scale. But internal organization can sometimes solve problems of opportunism. 142 Asset specificity. The model. β(k) = bureaucratic costs of internal governance. M(k) = governance costs of markets. k = index of asset specificity. Oliver E. Williamson (1932-) β(0) > M(0) because advantages of markets not offset by costs of asset specificity. But β declines faster than M as k increases (M' > β' k). ΔG(k) = β(k) - M(k). 143 Asset specificity. As asset specificity increases, ΔG becomes negative. At critical value of k, internal organization preferred to market. Cost β0 ΔG _ k k 144 Asset specificity. Economies of scale and scope. Markets can aggregate demands and take advantage of economies of scale and scope. Production-cost penalty for internal organization. Oliver E. Williamson (1932-) ΔC = steady-state production-cost difference between producing to one’s own requirements and the steady-state cost of procuring the same item in the market. ΔC always positive but decreasing in k. 145 Asset specificity. Cost ΔC + ΔG ΔC β0 ΔG _ k Market procurement has advantages in both scale economies and governance when optimal asset specificity is slight. ^ k k 146 Asset specificity. Cost ΔC + ΔG ΔC β0 ΔG _ k Internal organization has advantages when optimal asset specificity substantial. Little aggregation benefits when assets highly specific. ^ k k 147 Asset specificity. Cost ΔC + ΔG ΔC β0 ΔG _ k Mixed governance for intermediate levels of asset specificity: some make, some buy, and all are dissatisfied. ^ k k 148 Asset specificity. Cost Since ΔC always greater than zero, firm will never integrate for production-cost reasons alone ΔC + ΔG ΔC β0 ΔG _ k ^ k k 149 The hostage model. Oliver E. Williamson (1932-) But sometimes markets can solve problems of asset specificity without integration if cooperating parties can make credible commitments before the contract is signed. 150 The hostage model. (¼π, ¼π) Use non-specialized technology Party A Use specialized technology Don’t hold up (½π, ½π) Don’t give in Party B (0, -C) Hold up Party A Give in (0.9π, 0.1π) The hold-up threat in extensive form. Party A incurs a sunk cost C once the contract is signed. Party A’s optimal strategy is to use the lessefficient technology. (Why?) 151 The hostage model. (¼π, ¼π) Use non-specialized technology Party A Use specialized technology Don’t hold up (½π, ½π) Don’t give in Party B (-h, αh-C) Hold up Party A Now suppose that Party B supplies a hostage of value αh before the game begins. Give in (0.9π, 0.1π) The hostage — a credible commitment — is forfeit in the event of contract breach. 152 The hostage model. (¼π, ¼π) Use non-specialized technology Party A Use specialized technology Don’t hold up (½π, ½π) Don’t give in Party B (-h, αh-C) Hold up Party A h is the value of the hostage to B; α is the fraction of h that has value to A. Give in (0.9π, 0.1π) A money bond would have α = 1. But is an in-kind hostage a more credible commitment? 153 The hostage model. (¼π, ¼π) Use non-specialized technology Party A Use specialized technology Don’t hold up (½π, ½π) Don’t give in Party B (-h, αh-C) Hold up Party A If αh-C > 0.1π, A will choose the more efficient specialized technology. Give in (0.9π, 0.1π) Even if α = 0, B may have no incentive to hold up A. Hostage as a signal. 154 Fisher Body. Fisher Body pioneers closed car body. GM acquires 60 percent of Fisher Body in 1919 and initiates long-term contract. In 1926, GM fully integrates with Fisher. Why? 155 Fisher Body. Klein. Benjamin Klein Closed bodies required more firm-specific investment than open bodies. Contract worked well until 1925, when GM demand increased. Fisher brothers increased short-term profit by not making new investment. Integration (plus side payments) solved contractual hold-up problem. 156 Fisher Body. Other explanations. GM was trying to ensure access to specialized human capital. Provisions giving the Fishers power and incentive to hold up ended in 1924. Did the Fisher brothers hold up GM after the merger? 157 Moral hazard and monitoring. Moral hazard: the incentive to cheat in the absence of penalties for cheating. Armen Alchian (1919-) Harold Demsetz (1930-) Origins in insurance. Another kind of “plasticity” of behavior after contract is signed. If monitoring is costly, agents have incentive to supply less effort than they agreed to. Alchian and Demsetz: costly monitoring explains the organization of the firm. 158 Moral hazard and monitoring. Marginal products of team members not separately measurable. Team production. Members paid on the basis of the whole team’s output. Incentive to shirk. Each member receives all the benefits of shirking (leisure) but can spread the costs of shirking to other members. Inefficiency. Since everyone has the same incentives, all shirk, and the team ends up in a lowoutput equilibrium no one wants. 159 Moral hazard and monitoring. Solution. Team production. One team member becomes the “boss” and specializes in monitoring the others. But who guards the guardian? “Boss” also becomes the owner — the residual claimant — and is monitored by the market. Did Chinese bargemen hire someone to whip them? 160 Separation of ownership and control. Adolf A. Berle (1895-1971) with John F. Kennedy Big modern firms are not owner managed (as in Alchian and Demsetz story). Adolf A. Berle and Gardiner C. Means, The Modern Corporation and Private Property (1932). Separation of ownership and control. Managers “plunder” stockholders. 161 Agency theory. Michael C. Jensen (1939-) An agency relationship is a contract under which one or more persons (the principals) engage another person (the agent) to perform some service on their behalf that involves delegating some decision making authority to Divergence the agent. of interest between principal and agent. 162 Agency theory. Agency costs are the sum of: Monitoring expenditures by the Michael C. Jensen (1939-) principal. Bonding expenditures by the agent. The residual loss of misaligned incentives. 163 Separation of ownership and control. Agency costs of separation small compared to increased capital supply. Michael C. Jensen (1939-) Risk diversification benefits of passive ownership. Modern corporation has mechanisms to reduce agency costs. Stock market. Takeover market. Managerial labor market. Expert boards. 164 Who owns the firm? Owners are those persons who share two formal rights: the right to control the firm and the right to appropriate the firm’s residual earnings. Henry B. Hansmann (1945-) Formal not de facto rights. It is often efficient to assign the formal right of control to persons who are not in a position to exercise that right very effectively. Because giving those rights to others would create worse incentives. For example: why managers don’t have formal ownership rights. 165 Who owns the firm? Ownership falls to a class of patrons. Henry B. Hansmann (1945-) Capital suppliers. Customers. Input suppliers. Workers. Government. No one (but non-profits have donors). All ownership structures are really coops. 166 Who owns the firm? Henry B. Hansmann (1945-) Which patrons should own the firm? Balance the costs of contracting (with non-owning patrons) and the costs of ownership (for owning patrons). 167 Who owns the firm? Costs of contracting (with non-owners). Monopoly or monopsony. Henry B. Hansmann (1945-) Example: bottleneck stage. Contractual lock-in. Relation-specific assets. Asymmetric information. One party has specialized knowledge that is costly to transmit to others. 168 Who owns the firm? Costs of ownership. Monitoring (agency) costs. Henry B. Hansmann (1945-) All else equal, patrons who are least-cost monitors are most efficient owners. Collective decision-making. How to aggregate the interests of members of a patron class? Risk bearing. Which class in the best position to bear risk? 169 Who owns the firm? A “capitalists cooperative.” Because of asymmetric information, all other patrons have higher agency costs. Risk diversification benefits of investor ownership. The Common denominator of profit public reduces costs of decision-making. corporation. 170 Who owns the firm? Retail coops rare. Customers not homogeneous. Campus bookstores and monopoly. Most customer cooperatives are at the wholesale level. Customer cooperatives. Ace, True Value, IGA, Associated Press, Sunbeam Bread. Monopoly supply stage. Coops and franchises. Financial and insurance mutuals. 171 Who owns the firm? Analogous to customer coops. Monopsony processing stage. Common in agriculture. Supplier cooperatives. Ocean Spray, Land o’ Lakes, Cabot, Sunkist, much of French wine. The electric power grid? Problems of collective decisionmaking and flexibility? 172 Who owns the firm? Proletarian coops rare. Unskilled workers easier to monitor than other patrons. Most worker-owned firms in professional services. Workerowned firms. Law, medicine, consulting. Professionals can monitor one another more cheaply than can outsiders. Little physical capital per worker. Are professional firms consumer coops? Independent firms sharing common assets. 173 Who owns the firm? Some kinds of transactions pose special agency problems. Non-profit firms. Payments to third parties to provide goods and services (United Way) Support of public goods (PBS). Customers (donors) are the natural residual claimants. But monitoring by donors costly. Ownership by other patrons creates incentives to appropriate donor resources. 174 Who owns the firm? So managers “hold the firm in trust” for the donors. No residual claims – but that needn’t mean no profit. Reliance on formal rules and bureaucracy. Non-profit firms. Because market control mechanisms absent. Boards of directors chosen for impartiality not expertise. Important donors sit on board. Are non-profits really donors coops? 175 The transaction-cost dichotomy. Producing. Standard price theory. Knowledge free and perfect. Production knowledge as “blueprints.” Transacting. Fraught with hazards. Knowledge asymmetric and imperfect. Limited effect on production costs. 176 The economics of organization. Asset specificity and holdup. Moral hazard and “plasticity.” Ex post costs can affect ex ante choice of technology. 177 Maintained assumption. Oliver Williamson “A useful strategy for explicating the decision to integrate is to hold technology constant across alternative modes of organization and to neutralize obvious sources of differential economic benefit.” — Williamson (1985, p. 88) 178 Missing elements. Capabilities. Qualitative coordination. 179 Capabilities. [I]t seems to me that we cannot hope to construct an adequate theory of industrial organization and in particular to answer our question about the division of labour between firm and market, unless the elements of organisation, knowledge, experience and skills are brought back to the foreground of our vision (Richardson 1972, p. 888). G. B. Richardson (1924-) 180 Capabilities. Capabilities as the “knowledge, experience, and skills” of the firm. Similar capabilities. Complementary capabilities. G. B. Richardson (1924-) 181 Capabilities. “Where activities are both similar and complementary they could be co-ordinated by direction within an individual business. Generally, however, this would not be the case and the activities to be co-ordinated, being dissimilar, would be the responsibility of different firms. Co-ordination would then have to be brought about either through co-operation, firms agreeing to match their plans ex ante, or through the processes of adjustment set in train by the market mechanism” (Richardson 1972, p. 895). G. B. Richardson (1924-) 182 Capabilities. Production knowledge just as imperfect (and tacit and sticky) as knowledge in transacting. Loasby: standing on its head Brian Loasby the implicit presumption of transaction-cost economics. Transacting as a kind of production. 183 Coordination. As an entrepreneurial or innovative, not (only) a managerial or monitoring, activity. As involving changes in the structure of economic knowledge. 185 Organization and economic change. Oliver Williamson “The introduction of innovation plainly complicates the earlier-described assignment of transactions to markets or hierarchies based entirely on an examination of their asset specificity qualities. Indeed, the study of economic organization in a regime of rapid innovation poses much more difficult issues than those addressed here.” — Williamson (1985, p. 143) 186 Organization and economic change. Strength of the selection environment. “Good enough” not “optimal.” Organizational form may depend on the past. Path dependency. Organizational form may depend on the future. Structural uncertainty. 187 “Dynamic” governance costs. The costs of negotiating with, teaching, and persuading those who control or can cheaply create complementary capabilities. The costs of not having the capabilities you need when you need them. 188 Two scenarios. The Visible Hand. The Vanishing Hand. 189 Scenario 1. Creative destruction of existing external capabilities. Unified ownership and coordination overcomes "dynamic" transaction costs. 190 Antebellum America. High transportation and transaction costs. Small, localized, nonspecialized production and distribution. 191 The antebellum value chain. Stage 1 Middleman Stage 2 Middleman Stage 3 192 Postbellum America. Increased population and higher per-capita income. Lower transportation and communications costs. the railroad. ocean shipping. the telegraph. 193 The rise of the large corporation. Alfred D. Chandler, Jr., 1918- “… modern business enterprise appeared for the first time in history when the volume of economic activities reached a level that made administrative coordination more efficient and more profitable than market coordination. Such an increase in volume of activity came with new technology and expanding markets. New technology made possible an unprecedented output and movement of goods. Enlarged markets were essential to absorb such output. Therefore modern business enterprise first appeared, grew, and continued to flourish in those sectors and industries characterized by new and advancing technology and by expanding markets.” (Chandler 1977, p. 8.) 194 Refrigerated meat packing. Gustavus F. Swift (18391903). Great Union Stock Yards, Chicago, early 20th century. Before the railroads, meat raised and slaughtered locally Opening of the western range led to economies of scale in cattle raising. Live animals shipped to eastern cities. 195 Refrigerated meat packing. Gustavus F. Swift (18391903). Great Union Stock Yards, Chicago, early 20th century. Swift recognized possibilities for additional economies of scale. “Disassembly line” in Chicago. Ship refrigerated dressed meat to eastern cities. 196 Refrigerated meat packing. Gustavus F. Swift (18391903). Great Union Stock Yards, Chicago, early 20th century. Systemic reorganization of meat-packing industry. Required network of refrigerated railroad cars, ice houses, warehouses, and retailing outlets. Swift forced to integrate vertically to overcome dynamic transaction costs. 197 The rise of the large corporation. Cartel agreements and pools Alfred D. Chandler, Jr., 1918- Notoriously unstable Holding company Exchanging separate firm ownership for shares in a meta-company Multidivisional modern corporation Rationalization and professional management 198 The Chandlerian value chain. Stage 1 Stage 2 Stage 3 Stage 4 Stage 5 199 Why management? “In the capital-intensive industries the throughput needed to maintain minimum efficient scale requires careful coordination not only of the flow through the processes of production but also of the flow of inputs from suppliers and the flow of outputs to intermediaries and final users.” (Chandler 1990, p. 24.) 200 Why management? Product-flow uncertainty. High fixed costs demand high throughput. Thin markets lead to internal coordination. Management as a way to “buffer” uncertainty. Product standardization “pushes uncertainty up the hierarchy.” 201 Scenario 2. Creative destruction of existing internal capabilities. Development of institutions to support market exchange. 202 The Visible Hand. Adam Smith: Increasingly fine division of labor. Coordination through markets. Alfred Chandler: Visible hand of management replaces markets. 203 The Visible Hand. The managerial revolution is actually a manifestation of the division of labor. Management becomes a profession. The M-form decouples strategic functions from day-to-day management. Financial markets separate function of capital provision from management. Markets as a way to buffer uncertainty. 204 The Vanishing Hand. A new structural revolution? Increasing coordination through markets, including anonymous markets. Development of institutions, including standards, to support exchange. The visible hand is fading into a ghostly translucence. 205 The Vanishing Hand hypothesis. The Smithian process of the division of labor always tends to lead to finer specialization of function and increased coordination through markets. But the components of that process —technology, organization, and institutions — change at different rates. The managerial revolution was the result of an imbalance between the coordination needs of highthroughput technologies and the abilities of contemporary markets and contemporary technologies of coordination to meet those needs. With further growth in the extent of the market and the development of exchange-supporting institutions, the central management of vertically integrated production stages is increasingly succumbing to the forces of specialization. 206 The New Economy. Increasing population and income thicken markets. With the growth of knowledge, complementary capabilities in the chain of production become less similar. Institutions emerge to support specialized exchange. Modularity standardizes meta-rules, not products. Financial and other innovations, including new rights bundles. 207 The New Economy value chain. Stage 1 Stage 2 Stage 3 Stage 4 Stage 5 208 Technology and the New Economy. “It should be noted that most inventions will change both the costs of organising and the costs of using the price mechanism. In such cases, whether the invention tends to make firms larger or smaller will depend on the relative effect on these two sets of costs. For instance, if the telephone reduces the costs of using the price mechanism more than it reduces the costs of organising, then it will have the effect of reducing the size of the firm.” (Coase 1937, p. 397n.) But the division of labor is cumulative not comparative static. Internet increases extent of the market as well as reducing transaction costs 210