Auditory Processing Disorder

advertisement

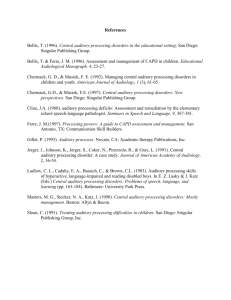

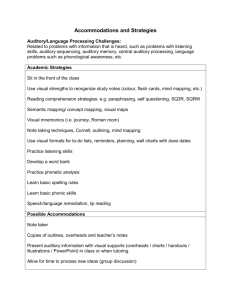

Auditory Processing Disorder Assessment, Diagnosis, Treatment and Controversies Defining Auditory Processing and APD • Auditory processing may be described as the “efficiency and effectiveness by which the central nervous system (CNS) utilizes auditory information.” (ASHA 2005) • ASHA defines Auditory Processing Disorder as “a deficit in neural processing of auditory stimuli that is not due to higher order language, cognitive, or related factors” (2005). • Bellis adds that the disorder occurs in the absence of any documented “neuropathological condition” (2002). Visual Processing Image received Image perceived General Characteristics and Symptoms • Auditory Processing Disorder can – – – – occur with or without hearing loss may run in families affect a person’s ability to interact socially affect children and adults with normal intelligence • Symptoms Exhibited by Preschool Children – – – – – Demonstrate delayed speech and language abilities or articulation errors (Ex. Substituting d for g) Have problems following directions at school or at home (Ex. “Find a book you want Mommy to read to you.”) Ask for repetitions frequently such as “What?” or “Huh?” Are more comfortable following daily routines once they have been practiced or learned rather than following verbal directions Perform better with visual cues or models (Bellis 2002) Symptoms of APD • Symptoms Exhibited by Elementary School Children: – – – – – – Behave as if a hearing loss is present despite normal hearing Exhibit articulation errors that are developmentally inappropriate Poor social skills (making and keeping friends) Express extreme frustration and often say, “I can’t do this!” or “I don’t understand” Poor reading or spelling skills Uses memorized phrases and sentences • Symptoms Exhibited by Adults: – – – – – Inappropriate responses to “wh” questions Poor expressive or receptive language Difficulty with reading comprehension, spelling and vocabulary Difficulty following long conversations Difficulty following verbal directions especially when involving multi-step directions (Bellis 2002) Referral • Audiologist should be contacted for a comprehensive hearing evaluation if some type of hearing or listening problem is suspected. • A referral by physician is not necessary for an Audiologist to assess hearing but it may be required by some insurance companies for reimbursement purposes. (DeBonis 2008) • Obtaining supplemental services at school: – First someone raises a concern (parent, teacher, school psychologist) about the child’s academic or communicative performance – Based on the severity of the concern : • (1) the child may be referred for special education assessment (can’t occur without the parent’s permission) • (2) the teacher may implement some classroom and related modifications (which do not require special education classification) • (3) continue to keep a close watch on the child’s performance and reconvene at a later time to reconsider the need for special education referral (Bellis 2002) Prevalence • There are “no authorized estimates of the prevalence” of APD. (ASHA 2005) • Chermak and Musiek (1997) estimated that APD occurs in 2 to 3% of children, with a 2-to-1 ratio between boys and girls. • 67% of ASHA certified SLPs who work in a school setting report regularly serving children with APD (ASHA 2005)) Areas of Deficiency • Auditory Processing Disorder is defined as having a deficiency in one or more of the following behaviors: – Sound Localization and Lateralization • refers to the ability to know where a sound has occurred in space – Auditory Discrimination • refers to the ability to distinguish one sound from another • most often used for distinguishing speech sounds, such as phoneme /p/ from phoneme /t/ as in “hop” and “hot” – Sound/Symbol Association • the ability to associate a symbol (a letter) with a sound (S with “ssss”). – Temporal Auditory Processing • the ability to integrate a sequence of sounds into words • the ability to perceive sounds as separate when they quickly follow one another – Auditory Figure Ground • refers to the ability to perceive the main message when other sounds are present (understanding a conversation in a movie theater) (ASHA 2005) Areas of Deficiency Cont. – Tolerance-Fading Memory • refers to weak short –term memory when information is presented audibly in the presence of distractible sounds – Sound Blending • ability to blend individual speech sounds together into a meaningful word (c-a-t cat) – Auditory Closure • ability to perceive information in which some of the information is missing (“it is raining and I ____ my umbrella”) – Decoding • problems are related to difficulties with phonics • may spell words phonetically, spell inconsistently, have reading problems, confuse similar sounding words (ASHA 2005) Diagnosis of APD • Diagnosis is also very difficult due to the fact that no two • APD can be formally diagnosed only by an Audiologist. individuals will exhibit the same symptoms or behaviors. (ASHA 2005) • Initially, an Audiologist should rule out hearing loss as a primary cause of the symptoms exhibited. • Factors that may help to determine if an APD assessment is necessary: – A child must be at least seven years old before a behavioral central auditory evaluation can be completed. – Hearing loss – Significant cognitive or language delays related to mental retardation, AD/HD, and/or Autism (Bellis 2002) Diagnosis • The following factors influence behavioral testing performance and should be considered when choosing the assessment battery: – – – – – – – Chronological and developmental age Cognitive abilities (attention, memory, education) Linguistic, cultural, and social background Medications Motivation Decision processes Motor skills (DeBonis 2008) • The Audiologist will take a complete history and a variety of auditory processes will be assessed such as: – – – – dichotic listening (listening to a different signal in each ear simultaneously) perception of distorted speech (which may consist of filtered speech or very rapid time-compressed speech) perception of nonverbal auditory stimuli (tone patterns) temporal auditory processing (sequencing and patterns, gap detection) (ASHA 2005) • APD screening can be conducted by audiologists, SLPs, and psychologists, using a variety of measures that evaluate auditory-related skills. • Other tests that are not administered in a sound booth should not be considered diagnostic tests for APD, however, they may be used to provide valuable information about the individuals overall listening and comprehension abilities. (Bellis 2002) Assessment Tools • A complete battery of testing may include the following: – – – – – – – – IQ tests – WPPSI (preschool), WISC (6-16), WAIS (16+) Academic tests – Woodcock Johnson Auditory Processing tests – SCAN-C & SCAN-A Auditory Skills Assessment (ASA) Test of Auditory Processing Skills (TAPS) Parent & teacher questionnaires – Behavioral Assessment Scale for Children (BASC) Conner’s Comprehensive Behavior Rating Scales Assessment Tools • Auditory Skills Assessement (ASA) • • Screen children as young as 3.6 years old – Measures auditory and phonological processing skills – Speech discrimination in noise – Sound blending – Rhyming – Sound discrimination – Sound patterning Used as a preliminary assessment of skills as well as for a re-evaluation tool to measure the success of interventions • Test of Auditory Processing Skills (TAPS) • • • • • Measures of various aspects of auditory processing as well as language processing Phonological processing (decoding and encoding) Auditory closure Short-term auditory memory for contextual and noncontextual information Language comprehension and making inferences Types of APD • There is no one universally accepted theoretical model of APD! • The Buffalo Model – Dr. Jack Katz • Looks at the relationship between patterns of performance on specific tests of auditory processing and learning difficulties in children. – Decoding – Tolerance-Fading Memory – Integration – Organization (Masters, Stecker & Katz, 1998) • • Dartmouth Medical School – Dr. Frankl Musiek Divided auditory processing deficits into subgroups on the basis of underlying brain-based etiologies. • • Bellis/Ferre Model The model is based on both the underlying neurophysiology and the relationship among different types of APD and language, learning and communication difficulties. (Bellis 2002) Bellis/Ferre Model • Three primary subtypes: • Auditory decoding deficit – • Integration deficit – • Difficulty with speech in noise, speech discrimination, sound blending, retention of phonemes, reading, speech to print may be poor. Difficulty with multimodality tasks that require inter-hemispheric transfer of information. Prosodic deficit – Difficulty with humor, multiple meanings and utilizing information in suprasegmentals of speech. • Two secondary subtypes: • Associative deficit – • May demonstrate receptive language difficulties, can not apply rules of language to incoming auditory information Output-Organization – Difficulty in sequencing, planning and organizing responses. (Bellis 2002) Management: Environmental Modifications • Management of APD should incorporate three primary principles and all are necessary for interventions to be effective: – Environmental modifications – Remediation techniques (direct therapy) – Compensatory strategies • Environmental Modifications: – Classroom Accommodations • Preferential Seating • Pre-teaching of new material • Frequently check for understanding • Rephrase vs Repeat • Provide a note taker • Use visual cues and modeling procedures • Amplification • Personal FM systems • Access to word processors and other technology (Bellis 2002) Management: Direct Therapy • Phonological Awareness Activities: – – – – Discriminating between speech sounds that are similar (pop/top) Discriminating between vowels (a in cat vs. e in egg) Segmenting words (CAT=C…A…T) Blending sounds into words (C…A…T=CAT) • • Before Therapy: Twhnkke, tvinjle kitsle rtaq. Hov I wnnddr wgat wou zre. After Therapy: Twinkle, twinkle little star. How I wonder what you are. • Auditory Closure Activities: – – Using contextual cues to fill in the missing pieces (Jack and Jill went up the ___) Noise is added to make activities more challenging. • • Before Therapy: O ing ol was a ry o ol After Therapy: Old King Cole was a merry old soul • Selective Attention and Localization Activities: – Training in dichotic listening (Bellis 2002) Management: Direct Therapy • Temporal Patterning Training: – Typically nonverbal exercises that address rhythm (clapping, tapping on the table) • Prosody Training: – Exercises to teach interpretation of nonlinguistic cues (tone of voice) • Computer-Based Therapy Programs: – – – Fast Forward Earobics Auditory Integration Therapy (Bellis 2002) Management: Compensatory Strategies • It is important to become an ACTIVE LISTENER! • The Whole Body Listening Approach • • • • Sit or stand up straight so that the body is alert Lean the upper body slightly or the head toward the speaker Keep your eyes on the speaker Eliminate unnecessary movement • Metacognitive and Metalinguistic Strategies • • • • • Self-instruction Self-regulation Using context clues Drawing inferences Rephrasing information Areas of Concern • Many clinicians are still skeptical about the existence of APD and point out three big areas of concern. (1) Disorders such as Autism Spectrum Disorders, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), language impairments and learning disabilities produce similar behaviors associated with APD. • Skeptical clinicians have deemed the auditory deficits a function of these broader disorders. (2) It is often difficult to diagnosis a problem if the problem can’t be seen. • No two individuals will exhibit the same symptoms or behaviors • no audiological assessments or medical physiologic tests that adequately differentiate APD from other disorders • Physiologic tests such as brain scans, electrophysiology and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) often fail to reveal any obvious structural or functional damage (3) Finally, an individual’s motivation to participate in APD screening may lead to problems making an accurate diagnosis. References • American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (1996). Central auditory processing: Current status of research and implications for clinical practice. American Journal of Audiology, 5 (2), 41-54. • American Speech-Language Hearing Association (2005). (Central) Auditory Processing Disorders [Technical Report]. Retrieved from www.asha.org/policy. • American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2005). (Central) Auditory Processing Disorders—The Role of the Audiologist [Position Statement]. Retrieved from www.asha.org/policy. • Bellis, T. (2002). When The Brain Can’t Hear: Unraveling The Mystery of Auditory Processing Disorder. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. • DeBonis, David A., et. al (2008). Auditory Processing Disorders: An Update for Speech-Language Pathologists. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 17, 4–18. THANK YOU! Jennifer Saliba