Trademarks_ - Columbia Law School

advertisement

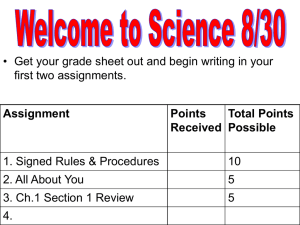

Trademarks, part II Jared Ellias Squirt v. 7-Up The Squirt Company v. The Seven-Up Company et al. (E.D. Mo. 1979) 207 U.S.P.Q. 12 V. Background Background 7-Up decided to create and market a lemon-flavored “thirst quenching drink.” They called this new drink “Quirst.” The Squirt Company already had a popular grapefruit-flavored drink on the market called “Squirt.” Furious, the Squirt Company filed a lawsuit alleging trademark infringement and demanding that the Court issue an injunction quashing Quirst. Are all Flavored Drinks Created Equal? Squirt Established, 1937 Carbonated, Grapefruit flavored drink that is opaque in color Ingredients: Carbonated water, corn sweetener, grapefruit juice, citric acid, oil of grapefruit, benzoic acid. Quirst Established, 1971 Non-Carbonated, Lemonade flavored drink that is yellowish in color Ingredients: Water, sugar, citric acid, potassium sorbate, sodium benzoate, gum arabic, Vitamin C. glyceryl abietate, natural flavors, brominated vegetable oil and artificial color. Advertisements Squirt Quirst "Put a Little Squirt in Your Life.“ "Switch to Squirt, Never an After Thirst.“ Squirt Quenches Quicker." (Plff's Ex. 47) "Squirt, When You're Thirstier Than Usual." Newspaper: “Try new Quirst for Thirst” “Quirst Quenches” “When I want to quench my thirst, I feel like a quirst” The Quirst Revolution Quirst was being rolled out across the United States. It was stocked in the Soft Drink section, next to Squirt. At the time of suit, 7Up was test marketing Quirst by distributing mixable powder. Why Quirst? The origins of the Quirst name are murky. 7-Up commissioned a study to find a name for its new beverage – it aimed to fill a gap in its lineup for a “thirst-quenching beverage.” Through a mall-intercept study in Philadelphia and Miami, 7-Up compared the reactions of consumers to 5 names Chug-A-Jug Fresh Up Quirst Refresh Thirst Burst Consumers were presented with each choice and asked “What does this name mean to you?” 52% of consumers considered Quirst to mean “thirst quenching. So, by virtue of its superior “thirst quenching connotation,” Quirst was born. Relevant Statutes Squirt brought suit for Trademark Infringement under the Lanham Act (15 USC 1114(1)) "Any person who shall, without the consent of the registrant – "(a) use in commerce any reproduction, counterfeit, copy, or colorable imitation of a registered mark in connection with the sale, offering for sale, distribution, or advertising of any goods or services on or in connection with which such use is likely to cause confusion, or to cause mistake, or to deceive; * * * shall be liable in a civil action by the registrant for the remedies hereinafter provided." Section 45 of the Act, 15 USC 1127, adds "The term 'colorable imitation' includes any mark which so resembles a registered mark as to be likely to cause confusion or mistake or to deceive." Weighting a Trademark Infringement Claim The Court considers: the strength or weakness of the SQUIRT mark, the degree of weakness of the SQUIRT mark, the degree of similarity between the two marks, the degree of similarity between the two products, the competitive proximity of the products, the alleged infringer's purpose in adopting its mark, actual confusion, and the degree of care likely to be exercised by consumers So we are considering the similarities between the products the trademarks, how close the two products are to one another in the marketplace, foul play, and the way the consumer reacts or is likely to react to the two products. Importantly, these factors are variable and no single one is determinative. What makes a strong trademark? The first step in a trademark analysis is to inquire into the strength of the plaintiff’s mark. A trademark’s strength is measured by its distinctiveness or its popularity An expensive advertising campaign that uses a mark establishes it as a strong trademark Squirt was an old trademark that had been widely advertised, and so the Court decided it was a strong trademark worthy of protection from infringement. The Degree of Similarity The second-step in a trademark infringement inquiry is to examine the degree of similarity between the two marks in question. The Court looks at the visual impression of the trademark and the sound of the word. The standard: “"the two marks should not be examined with a microscope to detect minute differences, but, on the contrary, should be viewed as a whole.“ Syncromatic Corporation v. Eureka Williams Corporation, 174 F.2d 649, 650, 81 USPQ 434, 434435 (7th Cir. 1949); cert. denied 338 U.S. 829, 83 USPQ 543 (1949). Similarities Compared Similarities: Dissimilarities: -Two words sound the same -First two letters of the names are not the same -Logos both ascend diagonally to the right with block text -The colors are different The Chicago Survey In an effort to establish similarities between the two marks, the plaintiffs introduced the Chicago Survey. This survey was conducted by the store intercept method. The Store intercept method is a convenience sampling method. Pros: Cheap, easy, and results can be compared across locations.. Cons: No randomness, no guarantee of significance, significant selection bias problem, significant non-response bias problem, potential for interviewer bias. If you think about how stores typically only cater to local consumers with the segregated patterns of American settlement, a sample bias is a major problem. Why Chicago? Chicago was an interesting site for the survey – Squirt had done little advertising there, and Quirst was neither advertised nor available for purchase anywhere. So the results reflect a response to the words “Squirt” and “Quirst” and the radio commercials that were played by the surveyor. Relevant Survey Results Question 4 – “Do you think SQUIRT and QUIRST are put out by the same company?” “Why?” 45% of the Sample mentioned either a similarity in name or sound between the two names. Competitive Proximity The Court determines that both are soft drinks that will be sold on the same shelves in most stores, so the threshold for finding trademark infringement is lower than it would be between two unrelated products. Oddly, the Court considers the common “thirst-quenching” attributes of each product to important. Actual Confusion The Court recognizes that 7Up’s massive ad campaign indicates that there is no element of foul play – the company is trying to establish its own brand, not free-ride off an already established one. Squirt offers anecdotal evidence that a consumer heard a Quirst ad and thought it was a Squirt ad. Squirt also offers another survey – the Maritz Survey, which was actually commissioned by 7-Up. Maritz Survey Another store-intercept survey, this one conducted in Phoenix, Arizona. Design: Conducted over three days at three stores, every day. All Customers who entered the store were given a coupon for 50 cents off any non-Cola drink. This coupon was meant to stimulate Soda purchases to increase the sample size. But doesn’t this introduce a problem of trying to generalize a conclusion about a population (normal soda buyers) that is not reflected by the sample (incentivized soda buyers)? On the way out of the store, customers were asked if they used the coupon. If they had, they were asked what kind of Soda they bought. The person administering the survey then looked through their groceries to verify the response. Importantly, they did not interview anyone whose soda was sitting in plain view in their grocery cart, since the sought-after data came from comparing the consumer’s perceptions of their purchases with the actual purchases. Maritz Survey, cont’d. Sample: 1,1016 persons interviewed 884 had used the coupon. 839 identified the brand of Soda they’d purchased. 70 thought they’d bought Squirt. Of those, 65 actually bought Squirt, 3 bought Quirst, and 2 bought Sprite. Maritz Survey, Cont’d Remember, this is the defendant’s survey. 7-Up Contends that: The number of people who bought Quirst rather than 7-Up is de minimis Court rejects this; 4.3% of people is not ‘de minimis’ in the billion-dollar soft drink industry On the other hand, Squirt contends that the 4.3% of the sample that made the mistake represents proof of actual conclusion. Thus, the debate is over survey methodology. The Court concludes that the survey does not show “actual confusion” since it is relying on the testimony of 3 people who are not available for cross-examination. However, the Court does agree with Squirt that the survey results represent evidence of a “likelihood of confusion.” All of the other instances of confusion involved consumers thinking they bought 7-Up when they really had Diet 7-Up or Caffeine Free 7-Up. The others, including Squirt/Quirst, all involved similar names. Phoenix Survey 8 different Supermarkets in Phoenix. Court decides to consider Phoenix and Chicago together since both are so similar: Both only surveyed women 25 and older who bought soda that day. Both were conducted by the same firms. Court concludes that the surveying methodology of both were fair and balanced. Survey Comparison Survey % that thought Quirst and Squirt were put out by same company % that thought Squirt and Quirst were produced by different companies % that wasn’t sure Chicago Survey 34% 55% 11% Phoenix Survey 23% 34% 43% Factors of Trademark Infringement Similarity between marks Plaintiff has strong trademark Close proximity of products Foul Play Low to moderate degree of care taken by consumers in distinguishing between goods Trademark Infringement? Kis v. Foto Fantasy Kis and Foto both own photo booths at Malls across America. Kis sued because Foto had unlicensed sketches of Tom Cruise and Marilyn Monroe on the sides of its booths, and Kis alleged that this was a copyright violation. Kis claimed that this copyright violation was steering customers towards Foto’s booth. They support this allegation with – what else – a survey They need to establish that the misuse of the trademark harms them directly in order to gain standing to sue under the Lanham Act. Without that finding, the Court cannot allow this action to go forward. Howard Survey Sample: He started by examining the demographic information of the customer base provided by defendant, and then verified it with independent observation over 3 days at a mall. He then conducted two focus groups – adults 18-42, and children 13-17 – and found that the phrase ‘endorses and approves’ means ‘business relationship’ to the adults and ‘probably gets money’ to the children. Defendant challenges the sample, saying it is ‘almost all Anglo’ He then conducted a second focus group for the phrase “If Tom Cruise has ‘endorsed or approved’ the photo studio, it means he is probably getting money from the portrait study” 87% of respondents – both children and adults – either ‘agreed’ or ‘strongly agreed.’ He then performed a mall sample, handpicking people to match the demographics of the defendant’s consumer base. He had two groups – a control group that had a packet that had a photo of defendant’s booths with no picture of Tom Cruise, and an experimental group that had a packet with a picture of Tom Cruise on defendant’s booth. Results: 7.1% of Control Group concludes that Tom endorses defendant’s booths, while 56.3% of the experimental group does. What’s with the 7.1%? He considers this to be ‘noise’ and deducts it from the 56.3% to conclude that the photos of Tom increase confusion 49.2% Defendants, obviously, attack this survey. First, the ‘survey universe’ was wrong The mall he used wasn’t one that had a photo booth Court says no; neither side had a booth, thus it was a clean sample that didn’t unfairly disadvantage one or the other it was an upscale Dallas mall Court says no; he tried to replicate the customer base. Second, the survey had leading questions Court says no; he used a control group Also, the pictures of the ‘photo booth’ weren’t actual ‘photo booths,’ thus the results don’t reflect market condition Court says no; the pictures were fine. The Court admits the evidence but is not swayed by it, and ultimately rules that there is no evidence of consumer confusion due to the exterior sketches. Quick Case Summary The case (in brief) Plaintiff made a Sherman Act claim that defendant is gaining a monopoly in the photo booth market that the Court rejects Without the ability to show injury (the Court attributes the downtown in plaintiff’s sales to fair competition), he lacks the standing to mount a challenge under the Lanham Act Court enters judgment for defendants. Lanham Act Claim Plaintiff claims damage due to ‘false endorsement’ due to sketches of Tom Cruise and Marilyn Monroe on the side of the defendant’s booths Court says no; those sketches are meant to demonstrate the booth’s unique ‘scan-in’ feature that Plaintiff’s booths do not share Therefore, the Court concludes there is no damage to plaintiff that is a ‘proximate result’ of the use of the Cruise sketches The Court finds that the plaintiff lacks standing under the Lanham Act, due to the lack of direct damages and the lack of evidence of things such as lost profits The Court even goes further and says that even if they WERE to find standing, there would still be no grounds for recovery. Importantly, the Court is not convinced that there is a real likelihood of confusion that the ‘sketched’ celebrities on the booths endorse the defendant’s products Sherman Act Claim Plaintiff also brings a Sherman Act Claim They find no significant barriers to competition, and find that the market is competitive and no danger of defendant becoming a ‘photo booth monopoly’ exists The Court then rejects the claim – there is no evidence of monopolistic behavior or an intent to monopolize. On these grounds, the Court rejects the claim.