Summer Assignments 2013-2014

advertisement

SUMMER AP

ASSIGNMENTS

Haines City High School

2013-2014

Table of Contents

Language Arts ................................................................................................. 2

Science .............................................................................................................. 7

Fine Arts .........................................................................................................18

Mathematics..................................................................................................19

Social Sciences ..............................................................................................35

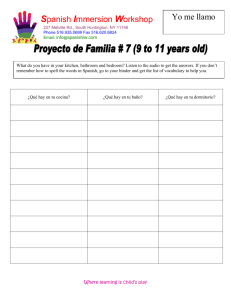

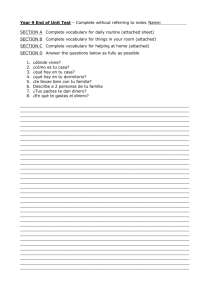

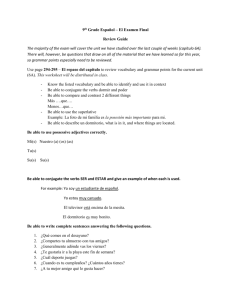

Spanish ...........................................................................................................42

1

Language Arts

2013 Summer Assignment

AP Literature Summer Reading

and Writing Assignment

Ms. Valk

Welcome to AP Literature! I am very excited about the year ahead of us. This summer I am asking

you to read two novels; The Secret Life of Bees by Sue Monk Kidd and The Old Man and the Sea by

Ernest Hemingway. My expectation is that you will read both novels and complete the work that is

assigned to you in this packet. The work will be due by the end of the first week back at school. Both

of these novels are very different, but I think you will find something to like in each one.

In this packet you will find a variety of assignments. One of the largest is the Reading Journal. It is

very important that you complete this activity. We will be doing Reading Journals for each of the

novels that we read in class this year, so I expect you to do these with fidelity. In the end, you will

benefit greatly from these journals as they will serve as analysis practice and a wonderful study guide

to refresh your memory before you take the AP Lit exam. I have given you some suggestions for

things to write about in the journal, but please know that these cannot be wrong. These Reading

Journals are your opportunity to pick apart the text, and therefore serve as your own interpretations

of the text.

You will also find a variety of Multiple Choice practice questions for each of the novels, as well as a

list of possible Free Response questions. I expect you to complete all of the Multiple Choice, and

choose one Free Response question to answer for each novel. Again, these will serve as practice for

the rest of the course and for the test and will give me a good idea of where each of you are in terms

of writing and analysis.

I will be available for questions throughout the summer. You may email me at my school email

address: mieke.valk@polk-fl.net. I may not check my email every single day over the summer, but I

will check it several times throughout the week so I will get back to you as soon as I can. Have a

great summer and enjoy the novels!

Ms. Mieke Valk

2

2013 Summer Assignment

AP Language and Composition

Mr. Johnston

Welcome

Welcome to Advanced Placement English Language and Composition. This is a primarily non-fiction

course where reading, writing, and analysis will support you in your college endeavors. Additionally you will be

prepared to take the AP Lang exam in the spring. To ensure that your brains remain fresh and engaged as

readers during the summer break, I ask that you make ONE selection from the book titles on this assignment

sheet and watch TWO documentaries from the documentary titles on this assignment sheet. Each book and

documentary title deals with a specific social issue so choose based on what appeals most to you! In August,

we will immediately examine these social issues in various contexts and begin in earnest to study the elements

of argument and rhetoric. I have chosen these assignments in order to prepare you for the upcoming course

as well as to give you a chance to find the types of material that you are interested in as the interests of you

and your peers will help to drive the course.

Assignment

1) Select and read ONE book from the list

2) Complete a type written Interactive Reader’s Log that includes ten entries

3) Select and watch TWO documentaries from the list (Must come from 2 different Categories)

4) Complete a type written Interactive Viewer’s Log for each of your two documentaries.

What should the Interactive Reader’s Log contain?

You will select ten quotations/ passages from the text that reflect the entire work. One strategy would

be to dividing the number of pages in your book by ten and use that as a guide for selecting quotations evenly

from the entire text. Your quotation selections should be passages that enrage you, intrigue you, engage you,

or cause you to wonder.

For each of the ten quotations, you will write a response. Responses should be between 150 and 200

words for each quotation and should address issues and purpose of the quote, not simply a summarization of

the plot or of the quote.

Some questions to consider when crafting your responses:

1) What is the writer’s purpose? Is it effectively achieved? Why or why not?

2) What use of language is especially effective? What purpose does it serve?

3) How does this quotation connect to the assertion or purpose of the work as a whole?

4) What is the writer’s tone in the passage? How is that tone achieved? What is the effect of that choice

of tone?

5) What created an emotional reaction in you as the reader?

6) What use of conflict is especially effective?

3

What should the Documentary Argument Analysis contain?

Part 1: Watch your documentary in its entirety and then evaluate the documentary for the overall main idea

(thesis). In one paragraph explain what the thesis of the documentary is and provide a supporting rationale (argument)

for your evaluation of the thesis.

Part 2: Select 20 details from the documentary that the filmmaker uses to support the thesis that you identified

in part 1. These details could come in the form of interviews, statistics, music type, audience being targeted, etc…

You are going to repeat this assignment for each of the TWO documentaries that you are to watch.

Some questions to consider when crafting your responses:

1) What is the writer’s purpose? Is it effectively achieved? Why or why not?

2) What use of language is especially effective? What purpose does it serve?

3) How does this quotation connect to the assertion or purpose of the work as a whole?

4) What is the writer’s tone in the passage? How is that tone achieved? What is the effect of that choice of tone?

5) What created an emotional reaction in you as the reader?

6) What use of conflict is especially effective?

Grading Criteria

The Interactive Reader’s Log assignment will count as a Level III grade (150 pts) towards the 1st 9 weeks grading

period. You will be assessed on the following criteria:

1) The assignment is complete (10 entries including both quotation and response)

2) The assignment is typed with 1 inch margins, 12 pt. Times New Roman (or similar) font

3) The quotation selections represent the work as a whole and clearly indicate understating of the work as a

whole.

4) The responses demonstrate thorough and insightful comments with regard to the writer’s purpose,

attitude/tone, and use of language

5) The writing demonstrates stylistic maturity with effective command of writing as well as a wide range of the

elements of writing and organization

The Documentary Argument Analysis assignments will count as two Level III grades (150pts) towards the 1st 9

weeks grading period. You will be assessed on the following criteria:

1) The assignment is complete (2 separate papers with a thesis identified and rationales supporting your

answers as well as the 20 details with explanations.

2) The assignment is typed, double spaced, with 1 inch margins, and 12 pt. Times New Roman (or similar) font.

3) The identified thesis should represent the work as a whole and clearly indicate your understating of the films

argument as a whole.

4) The responses demonstrate thorough and insightful comments with regard to the writer’s purpose,

attitude/tone, and use of language

5) The writing demonstrates stylistic maturity with effective command of writing as well as a wide range of the

elements of writing and organization

4

Sample Interactive Reader’s Log Entry

Interactive Reader’s Log

Chapter 1 “The Rules of the Game”

“Five men stumbled out of the mountain pass so sun struck they didn’t know their own names, couldn’t

remember where they’d come from, had forgotten how long they’d been lost. One of them wandered back up a peak.

One of them was barefoot, they were burned nearly black, their lips huge and cracking, what paltry drool still available

to them spuming from their mouths in a salty foam as they walked. Their eyes were cloudy with dust, almost too dry to

blink up a tear.” (3)

Response, wondering, comment, criticism:

Urrea’s use of imagery to begin his book startles me into wondering what horrible thing could have happened to

these people. The first sentence with the series of descriptions of these lost souls is gripping in its simplicity. Men who

are unable to “blink up a tear” who are “burned nearly black” with “lips huge and cracking” pilled me immediately into

their mystery. What could have happened to cause such harm to these people? The title of the book foreshadows

terrible things with “devil” in the title, so I’m immediately curious to find out how all of the opening events tie together.

I didn’t expect a nonfiction book to be written with such and intense, almost poetic style. I have no doubt from the

beginning traveling “The Devil’s Highway” could not be a happy journey. Since I live in Texas, I am aware the issues

surrounding illegal immigration are complicated and unhappy, but that doesn’t change how disturbing the opening of

the book is. I’m interested to learn how Urrea will expose this activity.

Sample Documentary Argument Analysis

Documentary’s Thesis and Rationale

The filmmaker’s thesis in the documentary Crips and Bloods: Made in America is that the two most

violent and largest rival gangs in America were formed not out of hatred for one another but out of a common race issue

that both of the gangs face. The documentarian, Stacy Peralta, does not simply document the formation and history of

these two gangs, but seeks to provide understanding of gangs in general by showing the viewer that the issues that face

minority groups in America today allow for gangs to exist and function relatively unchecked. An example of this is given

within the first five minutes of the documentary as the surviving members of the original gangs were interviewed and

were able to discuss the environment of the mid-sixties when the gangs were first formed.

Details to support thesis and Rationale

1) Graphic images of a gang gunfight and class war are shown in order to hook the audience into the

story that the filmmaker is attempting to relay. (00:03-01:28)

2) Interview with Bo Taylor, former Schoolyard Crip, founder of UNITY ONE, a privately funded

organization dedicated to peace making and the transformation of gang members into productive citizens, who relays

the history of the gang as well as what it has turned into and how to combat the issues that the gangs now face. (04:3206:29)

What if I need help on the assignment during the summer?

If you have any questions over the summer, please feel free to contact me for assistance:

Mr. Johnston- Nicholas.Johnston@polk-fl.net

I generally check email several times a day during the school year and several times a week during the summer

and will be more than happy to answer any question you may have.

Due Dates

Hard copies of your assignments will be submitted to me at the beginning of class on your first day of class.

5

Selections

A Warning: Because our course seeks to engage with a wide variety of topics and varying positions on those

topics, some of the following selections may deal with mature content. Check with your parents or guardians on the

types of selections that you are reading or watching before you make the final decision to begin your assignments.

Assassination Vacation

The Right Stuff

Books: Select ONE

Food

The Omnivore’s Dilemma

Fast Food Nation

Environmental

Desert Solitaire

Since Silent Spring

One River

Pilgrim at Tinker Creek

Walden; or Life in the Woods

Soulcraft: Crossing into the Mysteries of Nature and

Psyche

Historical

Guns, Germs, and Steel

Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Survive

The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest

Pandemic in History

Current Issues

Factory Girls

The Devil’s Highway

There Are No Children Here

The Forever War

Popular Culture

The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big

Difference

Freakonomics

Blink

Travel

A Walk in the Woods: Rediscovering America on the

Appalachian Trail

Mountains Beyond Mountains: The Quest of Dr. Paul

Farmer, A Man Who Would Cure the World

At the Edge of the World

Documentaries: Your selections must come from

two different categories.

Food

Travel

180 Degrees South

Ride the Divide

Supersize Me

Fat, Sick, and Nearly Dead

I Like Killing Flies

Forks over Knives

Food Matters

Popular Culture

Bowling for Columbine

Loose Change 9/11: An American Coup

Fahrenheit 9/11

Waiting for Superman

The September Issue

The Parking Lot Movie

The People versus George Lucas

Trekkies

Nerdcore Rising

Environmental

An Inconvenient Truth

If a Tree Falls

Blue Gold: World Water Wars

6

Science

2013 Summer Assignment

AP Biology

Ms. Blaze

Biology summer assignment

Chapter 1

For this assignment, you will view this Prezi: http://prezi.com/6gn_5zw5k6yn/ap-bio-introductorypresentation/http://prezi.com/6gn_5zw5k6yn/ap-bio-introductory-presentation/ . Study it in detail.

Watch this: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i8wi0QnYN6s Sci Show: Scientific Method.

Then answer 2 of the following 4 questions in 1-2 well written paragraphs each. Make sure to include information

from the notes and the videos.

1. Explain how science works as a process.

2. Contrast science with other ways of looking at the Universe.

3. Explain why biology is a science.

4. Give a brief explanation of how life is organized across several domains of space and time, and why this

organization is necessary.

Next: search Sci Show on YouTube and find 1 interesting video (to you) that is over 5 minutes. Come prepared to

summarize the video to the class when school begins again. Also, bring in the link.

Learning

For this assignment, you will read the essay “Learning (Your First Job)” by Robert Leamnson and answer the following

questions. These may be typed or hand-written. The essay was written with freshmen college students as the

intended audience. However, the AP program is as difficult as college classes. Simply mentally replace the word

college with AP as you read.

Complete the following questions before reading the attached essay. Answers should be at least 1-2 well written

paragraphs.

1. What is your own definition of learning?

2. What are your learning habits? How do you typically learn?

Complete the following questions after reading the attached essay. Answers should be at least 1-2 well written

paragraphs.

1. Discuss the connections between learning and biology.

2. Describe your plan to become a successful learner.

7

Leamnson

Learning

(Your First Job)

by

Robert Leamnson, Ph D

Introduction (Don’t skip this part)

These pages contain some fairly blunt suggestions about what to do in college.

Some of them may seem strange to you, some might seem old fashioned, and most will come across as labor

intensive. But they have worked very well for many students over the past 20 years, since the first edition

came out. This edition is more up to date, but the basic message has not changed much.

A fundamental idea that you will encounter over and again, is that learning is not something that just happens

to you, it is something that you do to yourself. You cannot be “given” learning, nor can you be forced to do

it. The most brilliant and inspired teacher cannot “cause” you to learn. Only you can do that. What follows

are some fairly explicit “learning activities” or behaviors, but they are all your activities, and now and then

those of your fellow students. But there is also a basic assumption underlying these ideas, and that’s that you

do want to learn something while getting a diploma. Without that desire, nothing will work.

Some words we need to understand

It happens, too often, that someone reads a passage or paragraph, as you are, and gets an idea very different

from what the writer intended. This is almost always because the reader has somewhat different meanings for

the words than did the writer. So that we don’t have that problem here I’ll make clear the meanings I intend

by the words I use.

We’ll start with:

Learning:

While few people think of it this way, learning is a biological process. It is indeed biological because

thinking occurs when certain webs (networks) of neurons (cells) in your brain begin sending signals to other

webs of neurons. You, of course, are not conscious of this process, but only of the thought that results. But

there is no doubt that thinking is the result of webs of cells in your brain sending signals to other webs.

How can knowing what causes thought help in the learning process? Start by considering that human

learning has two components:

1) Understanding

2) Remembering

Either of these by itself is not sufficient. Knowing a bit about how the brain works when you’re thinking will

help you to see why both understand and remembering are necessary for learning.

Anytime you encounter a new idea (and that, after all, is why you are in college) you need to “make sense”

of it, or, to understand it. And if you are actually trying to (1 Leamnson) make sense of it, your brain is firing

a lot of webs of neurons until one or more of them “sees” the logic or causality in a situation. Understanding

sometimes comes in a flash and we feel, “Oh, I get it!” Other times it takes repeated exposure or the use of

analogies until we finally “get it.” But if we never get it, then we still don’t understand—we haven’t tried

enough circuits in the brain.

So, right from the beginning, making sense of what you read or hear involves focused attention and

concentration, in other words, “brain work.” I’m confident that almost all college students “could”

understand what is required of them by focusing attention on what is being read or heard, and stick with it

until the thoughts in their heads pretty much matched those of the speaker or writer.

Unhappily, this is not the way all students in college behave. The most frequent complaint I hear from

college instructors is that too many of their students are simply “passive observers.” So the big rule about

understanding is that it cannot be achieved passively. It demands an active and focused mind.

Some very bright students find little difficulty in understanding what they hear or read. But some of these

smart people get very poor grades and sometimes drop out. The reason is, they neglect the second part of

learning, which is remembering.

8

For most people, I suspect, remembering is more difficult than understanding. I would suggest that this is

because few people know much about memory, or that it is likewise a biological process involving the firing

of webs of neurons in the brain. Most people think of memories as ideas, pictures, or events that are lodged

somewhere in their heads, and these places simply need to be “found.” The fact, however, is that memories

are not things always present somewhere in our heads. Memories must be reconstructed each time they are

remembered. This reconstruction, in biological terms, means firing up

almost the same webs of neurons that were used to perceive the original event. This

would seem to be easy, but it is not in most cases. Here’s the reason.

Use it or lose it

These webs I’ve been speaking of are networks of connected neurons. The details

do not need to be understood, but the fact is, the connections between brain cells are not

necessarily permanent. Much of our brain is not hard wired. One can think of neurons as

having a big, important rule, “if the connection I made gets used a lot, it must be doing

something important or useful, so I will strengthen the connection so it doesn’t fall

apart.” And that’s exactly what it does (even though, in fact, it itself doesn’t know what

it’s doing.) Now the bad news. If a neuron makes a connection that does not get used

(no matter how useful it might have been) it breaks the connection and it’s probably gone

forever. In short, neural circuits that get used become stable, those that do not get used

fall apart.

2

Leamnson

So it is that we can understand something quite clearly, and some time later not be

able to remember what it was we understood. The biological explanation is that the “web

of understanding” was not used enough to become stable, so it fell apart.

If you’ve followed all of this you probably see the bad news coming. If learning

means both understanding and remembering, we have to practice what we understand.

Without rehearsal, that fantastic circuitry that enabled our understanding will gradually

disintegrate and we can no longer reconstruct what we once understood.

Some readers are no doubt wanting to get on to the “tricks” for getting high

grades. But for a lot of college courses, getting a high grade involves only one trick—

learn the material. Learning, as described here, is the trick that always works. Learning

is the goal—keep that always in mind through the rest of these pages. Grades will take

care of themselves.

The Classroom

The classroom might be very traditional—a collection of students in chairs and an

instructor at the front—or people seated at computer terminals, or alone at home with the

computer. So long as these are in some way “interactive” with an instructor, the

following suggestions will be valid and useful.

The reason something must be said about so commonplace a thing as the

classroom is that too many students see it incorrectly and so they waste a highly valuable

occasion for learning. The most common misconception is that the class period is that

occasion when the instructor tells you what you need to know to pass the tests. Seen this

way, it can only be a dreary thing, and from this perception flow a number of bad habits

and behaviors that make learning more laborious and less interesting that it can be and

should be.

“Taking” notes

I would like to see the expression “taking notes” removed from the vocabulary

and replaced with one often used in Great Britain, that is “making notes.” “Taking”

implies a passive reception of something someone else has made. It too often consists of

9

copying what’s on a chalkboard or being projected on a screen. Copying from a

projected image is usually quite difficult and trying to copy what someone is saying is

nearly impossible. Attempts to take notes in this way produces something that is usually

quite incomplete, often garbled and has the awful effect of turning off the listening part of

the brain. We are not capable of focusing attention on two different activities at the same

time. So we miss what an instructor is saying while we concentrate on writing what he

has already said, or copying from the board or screen. Some instructors compensate by

making notes for the students and passing them out. This practice can help the better

students—those who already know how to learn—but for many others it only makes

matters worse. For a passive person, having a set of teacher-prepared notes means that

they now have nothing to do during the class period. So they just sit, or daydream, or

doze off, and often quit coming to class altogether. Why not, if it’s all in the notes? Two

more definitions will help to see that this is a recipe for failure.

3

Leamnson

Information and Knowledge

Even college professors and authors of books often confuse these words or use

them interchangeably. In fact they mean very different things. Let’s start with

information. The world is awash in information. All the books in the library have

information, as do journals, magazines, and the uncountable number of websites and

postings on the internet. All of this information is transferable from one medium to

another, sometimes with lightening speed. None of it, however, is knowledge! The

reason being that knowledge can only exist in someone’s head. Furthermore, the

expression “transfer of knowledge” is ridiculous because it describes the impossible.

This might be a novel or surprising idea so let’s examine it further. Suppose your

chemistry teacher has a correct and fairly thorough knowledge of oxidation/reduction

reactions. Can this knowledge be transferred to you? How wonderful if it could be.

Something like a ”transfusion” or “mind meld” and you know instantly what he/she

knows! None of that is possible. All your teacher can give you is information, and

perhaps the inspiration for you to do your part. This information is always in the form of

symbols. These symbols might be words,—spoken or written—numbers, signs,

diagrams, pictures, and so on. You cannot learn anything unless you have previous

knowledge of the meaning of the symbols. As a clear example, you cannot learn from

someone speaking Farsi if you know only English, no matter how accurate and useful the

information embedded in that language. This idea—new knowledge depends greatly on

prior knowledge—will come up again later.

But if, happily, you can indeed “make sense” of new information on chemical

reactions (or anything else) you can then construct your own knowledge by using the new

information and incorporating it into your prior knowledge base. But, as noted above,

this will involve using some not-used-before neural connections, so if you want to

remember what you now understand, you must practice, that is review a number of times,

or use the new knowledge repeatedly to solve problems or answer questions. Remember

the rule about new knowledge—use it or lose it.

So, what do I have to do?

All of this talk about brains, information, and knowledge is not just abstract

theory. It is the way we learn. The way to learn, then, is to align your own activities with

those behaviors we already know will work.

Time

Time is nothing at all like the way we talk about it. How often do you hear

10

someone say that they “didn’t have time?” It’s a perfectly meaningless expression.

When you wake up on a Sunday morning, you have exactly 168 hours of time until the

following Sunday morning. And everybody on the planet gets 168 hours. No one ever

has any more or any less time than anyone else! Time cannot be “found,” nor

“stretched,” nor “compressed,” nor “lost.” It cannot be “saved” or “bought,” or in any

other way “managed” for any realist meaning of the word “manage.” So why do we use

all these meaningless expressions? It’s because they let us avoid the embarrassing

4

Leamnson

process of examining our priorities, a ranked list of those things we hold to be important.

Sleeping is a high priority for everyone—it’s a biological necessity, like food—so we all

spend a fair amount of our allotted time blissfully unconscious. Now, what about the rest

of our 168 hours? For someone who has to work part time to meet expenses, work is a

high priority activity and they show up on schedule and on time because losing the job

would mean losing the income and the consequences would be serious. So, after

sleeping, eating, working, and, one hopes, going to classes, the rest of our 168 hours are

spent doing whatever we find personally important. For some, doing assignments,

reading books, writing reports and the like are important, so they always get done. For

some others, TV, “hanging out,” the internet, and partying are of primary importance, and

sometimes they fill up so many of the 168 hours available that there is nothing left at the

end of the week. Remember, no one gets more than 168 hour, so anyone who thinks they

can “do it all” is always going to “run out of time.”

It’s your priorities and not the clock that will determine the outcome of your

college experience. If it’s really important, it will always get done, and always at the

expense of the less important.

Studying

You and your teachers will use the word “study” frequently, and always assuming

that it means the same thing to everyone. But it doesn’t. For way too many college

students, particularly in the first year, study never happens until just before a test.

Teachers are amazed at the idea, but many students simply see no reason to study if there

is no test on the horizon. So here in a nutshell is a most serious misunderstanding

between college teachers and beginning students. For teachers, the purpose of study is to

understand and remember the course content; for students the purpose of study is to pass

the tests.

Now in an ideal world these would amount to the same thing. But in the real

world, unfortunately, you can pass some tests without learning much at all. This is not

the place for me to beat up on my colleagues, but some do produce truly simple-minded

exams that do not require much by way of preparation. So here’s an absolutely heroic

idea if you find yourself bored with a class; try learning more than the teacher demands.

Wake up your childhood curiosity and ask why other people find this discipline so

interesting that they spend their lives at it. I can about guarantee that there are bright,

articulate, and interesting writers in every college discipline. Find a good book and read.

That way you’ll learn something even if the teacher doesn’t demand it.

But such “gut” courses might be rare in your college. The one’s that cause

trouble and hurt the grade point average are those where the teacher expects serious

learning, but leaves most of it up to you. How do you cope with that?

5

Leamnson

Tough Courses

11

What makes a course tough? Well, sometimes it only means large amounts of

material, many pages to read, lots of writing assignments, and the like. But the really

tough course is one where the subject itself is complex, or presents difficult problems for

the learner to deal with, and often goes faster than students would find comfortable.

Suppose we add to that a super-smart teacher, but one who simply assumes you know

how to learn, and sprays information like a fire hose. For a typical first year student this

is the famous “worst case scenario.” The whole purpose of my writing is to help you

cope with worst case scenarios.

During the Lecture

In these tough courses the first idea you must abandon is that you can sit, “take”

notes, and worry about it later. Here’s another key idea to bring with you to every lecture

period. Worry about it now.

You can look upon your teacher as an adversary, something that stands between

you and a diploma, but that’s a defeatist and erroneous idea. It’s better to think of the

instructor as your private tutor. Most teachers welcome a considered question on the

content. They nearly all resent questions like, “is this going to be on the test?” You

don’t do yourself any favors by giving your teachers the impression that you’re a lazy

goof off trying to slide by with minimal effort. Teachers can often pack a wealth of

important information in what just sounds like an interesting story. They do not seem to

be “giving notes.” It’s a serious mistake to get comfortable and day dream. When notes

are not “given,” then you have to make them, and that’s anything but relaxing. It takes

careful listening, concentration, and a focused mind to pick out the important nuggets

from what appears to be a non-stop verbal ramble. A casual remark like, “there are

several reasons we believe these things happen,” is a clear clue that something worth

knowing is coming. As noted, some teachers may pass out notes that they have made,

and these might contain an outline of what’s important. A fair number of college faculty

have learned that this only encourages passivity and cutting classes. (It’s quite easy to

get the notes from someone else, and if it’s only the notes that are important, why spend

time sitting in a classroom?) Some teachers have discovered that students can only be

prodded to serious mental activity if they don’t provide prepared notes. This might seem

mean spirited to you, but they’re just trying to activate your brain.

Under conditions described above, you, to make notes from which you can learn,

have to be attuned to what’s being said. Not every sentence that drops from an

instructor’s mouth is going to contain some pearl of wisdom. Much of it is “filler”—

rephrasing, giving examples, preparatory remarks for the next point and so on. You have

to learn quickly where the gems are. Sentences you hear stay in the short term,

immediate recall part of your brain for only a couple seconds. During that brief time you

have to make the decision as to whether you’ve heard something important or just filler.

If it was important you have to get the gist into your notes, even if that means not being

6

Leamnson

quite so attentive so far as listening goes. Once it’s down, refocus and wait for the next

useful idea.

In short, teachers who do not “make it easy” by doing all the work, are, in fact,

doing you a favor. What is often called “deep learning,” the kind that demands both

understanding and remembering of relationships, causes, effects and implications for new

or different situations simply cannot be made easy. Such learning depends on students

actually restructuring their brains and that demands effort. Such learning can, however,

be most satisfying and enjoyable, even as it demands effort. I always think of serious

12

learning of any academic subject as being something like practice for a sport or with a

musical instrument. No one is born with a genetic endowment for playing either the

trombone or ice hockey. These are both developed skills and both take long periods of

concentration and effort. Both are simply difficult, but how satisfying they are as small

elements are learned and burned into our brain circuits! How enjoyable to become

proficient! It’s exactly the same with academic matters. Give it a try.

About Interests

An obvious response to the thoughts just expressed might be, “but I like hockey, I

have no interest in history,” or chemistry—whatever. That may well be true, but what is

not true is the assumption that these interests are natural—something you came into the

world with. Here’s another strange but important truth; all of your interests had to be

learned! This is a small example of a paradox. You need to know something about a

musical instrument, or a sport, or indeed, an academic subject, before you can judge

whether or not it’s interesting. But if you hold the belief that you cannot learn anything

until or unless it’s interesting, then you can never get started on anything new.

I was always impressed with my senior biology majors who came to my office

and got around to talking about their courses in psychology, or philosophy, or art history.

These students gave every discipline a chance to prove itself. Instead of depending on a

teacher to “make it interesting,” they studied it on their own to discover why other folk

found it interesting enough to write books about it, and teach it in college. You would do

yourself a great favor by developing this “curiosity habit” as early on as you can.

Between Classes

When a teacher happens not to assign some specific work to be done for the next

period, a disturbing number of beginning students simply assume that means that nothing

at all needs to be done. And it so happens that a lot of college instructors do not assign

each time some reading, or writing, or problem solving to be done. And if you had an

orientation session, someone probably told you that “they” expected you to spend three

hours on each of your subjects, for each hour in class! That usually comes to an amazing

45 hours a week. Most students find that unreasonable and unnecessary, and I tend to

agree. But the proper response to an excessive demand is not to do nothing. A huge

number of new college students, when told to study but given nothing specific to do,

simply do nothing. So here are some realistic suggestions for study outside class time.

7

Leamnson

Fill in the Notes

As noted above, it’s essential during a lecture to produce some record, no matter

how sketchy, of what was presented during that period. A most useful and highly

recommended way so spend half an hour or so of study time is to make sense of these

notes, and most importantly, turn lists and key words into real sentences that rephrase

what went on. When memory fails, that’s the time to use resources. Sometimes your

best resource is the textbook. Even if no pages were assigned directly, there is a very

high probability that the text contains, somewhere, a good, or better, description of what

the teacher had presented. You may have to search for it, but tables of contents, chapter

headings and the index will lead you to what you need.

Now, read with the intent of re-discovering what was presented in class. Read

with understanding as the goal (this will feel different than reading because it was

assigned.) People who know the education process thoroughly say that most learning in

college goes on outside the classroom. So it is that you will know more about the day’s

material after this “filling in” process than when you first heard it.

13

But there is a further critical element here. You must write in your notes, in real

sentences, what you have learned by the reading. Writing has an enormous power to fix

things in the mind. Always write what you have learned. (Once in a while a short

paragraph that summarizes or paraphrases an important aspect becomes exactly what you

need on an exam. You will almost certainly remember it because you’ve already written

it before.) There are two other good resources for filling in the notes should the textbook

be insufficient. These are your classmates and the teacher (or tutor if one is available.)

Huge studies have been done to find out just what “works” for college students.

What, in other words, did the truly successful students actually do that the unsuccessful

ones did not? The first of the two most outstanding findings was that successful students

had gotten “connected” to those of their teachers who were open to talking with students

(and there are a lot of these.) The intent was not merely social. The point was to become

more familiar with course content by simply discussing it with an expert. Remember, the

successful students said that this was the most important thing they did to be successful.

So you don’t have to wonder about it; the experiment’s already been done.

The second most important activity for success was to form small study groups, or

pairs, with the express purpose of talking about the course content, their notes, and

assigned work. Working together on assignments and problems is not cheating. Copying

without learning is cheating. Discussing the details of an assignment or problem is just

cooperative learning—one of the most useful habits you can develop in college. (I’m

perfectly aware, by the way, that getting some guys together to discuss psychology

sounds like a pretty “nerdy” thing to do. Well, so what? Really smart college students

have no problem stealing a page from the “Nerd’s Handbook” if it means learning more

and doing better.)

8

Leamnson

Assignments

Here again, attitude will influence how you react to assigned work. To view it as

paying dues, or taxes, or as mere busywork that teachers insist on out of habit, is to

squander an excellent learning opportunity. Inexperienced students see assignments as

something to be done; experienced students see them as something to be used. Look on

every assignment as a clue from the teacher—what he or she considers important enough

to spend time learning. Assignments, in most cases, are solid, meaty chunks of what’s

important. Don’t just do assignments with minimal effort and thought, use them to learn

something new.

Thoughts on verbalization

Here’s another experiment that’s already been done and you won’t have to repeat.

Things do not go into memory as a result of thinking about them vaguely—in the

abstract. It has been well documented that thought, to be useful, must be verbal. Now all

that means is that, to be remembered, and so useful, your thought on a topic needs to be

either spoken, aloud, to another person, or written on paper. (Recall the earlier idea that

information can only move by means of symbols, words spoken, signed, or written.) In

either case, good English sentences are needed—not just word clusters. You need verbs.

Who did what to whom? How does this thing cause that thing to happen? These facts

support the suggested need to talk to teachers and classmates and use writing assignments

to say what’s true or useful. And here’s a bonus! If you have filled in your notes and

discussed a topic with a classmate, even if it only took 30 minutes, you will be prepared

for the next class. That means you will have something to say should there be a “pop

quiz,” or if the teacher starts asking questions. Or, just as well, you can start the class by

14

asking a well-prepared question on the last period’s material. Trust me—the teacher will

notice, and remember, favorably.

Access and high technology

There have been some noisy claims that today’s students will turn out to be the

best educated so far, because they have access (by way of the internet) to unimaginably

more information than any previous generation. I have reservations about this claim for

several reasons. For one thing, the internet has been with us for quite some time, and

those of us who teach college are still looking for the promised improvement. Results

should have showed up by now.

The principal reason, however, goes back to the fundamental difference between

information and knowledge. Knowledge is what has the potential for improving the

individual and society. But websites are completely devoid of knowledge; all they have

is information (and not all of that is reliable!) No matter how many websites you have

access to, none of them can do anything for you unless you can make sense of (and

evaluate) what you find there.

And here is another little paradox I discovered by observing the differences

between accomplished college seniors and most first year students. Instead of getting

9

Leamnson

knowledge from the internet, you need to have a lot of knowledge beforehand to make

sense of the ocean of information you find there.

It’s tempting to believe that access to more information is going to make college

easy. But it’s just a temptation. You fall for it at your peril. The internet is a tool, and a

very useful one, but as with all tools, you have to be knowledgeable to use it profitably.

Exams

I have intentionally put last what most new college students consider to be the

single most important aspect of college—tests and exams. My reason for this approach is

simple. If you attend class regularly, listen with attention, make the best notes you can,

fill them in later (preferably with a study partner or two), verbalize your thoughts, and

use assignments as learning tools, then you would be ready for a test at any time. Learn

as you go means you’re always prepared.

That is, of course, a bit overstated. In the real world, a “big test” in the offing

makes even the best student nervous, and everyone bears down to some degree to get

prepared. For someone who has done it all wrong, whose notes are just words copied

without context or explanation, who does nothing between classes, and who never

discusses coursework with anyone, and who does assignments thoughtlessly—just to

have something to pass in—an upcoming exam is justifiably terrifying. It’s these

students who do everything wrong who ask embarrassing questions like, “What’s this test

going to cover?” or, “What chapters should we study?” They’re clueless and they know

it.

But let’s assume you’ve done all the right things. You still want to do the best

you can, and that means review, because stuff tends to slip out of memory, particularly

when you have three or four other classes to attend to. But I mean “review” literally. It

means learn again, not learn for the first time. No one can “learn” the content of 15 or 20

lectures in two days. Unless it’s all completely trivial, that just can’t be done. Learning a

second time (real review) on the other hand, is a snap compared to learning from scratch.

So, review for an exam should not be stressful. If you’re in a state of panic because of an

exam it’s because you’ve been doing the wrong things all along.

But you’re smart. You’ve done the right things. How do you do the review?

15

Don’t go it alone

If you’ve done the right things you already have a study partner or two. Schedule

firm times and places to spend an hour or so reviewing. Estimate how many days it will

take to review all the material and get an early start. Don’t worry about reviewing too far

in advance of the exam! If you talk about the content and write summary paragraphs or

descriptions, make labeled diagrams, or solve problems on paper, you won’t forget—it’s

guaranteed. Remember, stealing a “nerd trick” will make you a better student.

Get Satan behind thee

The absolute worst thing you can do is to fall for the crazy notion that the way to

prepare for an exam is to compress it all in the last 12 to 18 hours before the test, and

10

Leamnson

keep it up right to the very last minute. I could always predict with great accuracy who

was going to do poorly on an exam. They were red-eyed, gulping coffee to stay awake,

and frantically flipping pages even as the test papers were being distributed. They had

done it all wrong.

“Pulling an all-nighter,” as the cute expression has it, is based on the completely

erroneous belief that the only thing that college work requires is short term memory.

Were that true, “last minute” study would make at least some sense. But the truth is,

most college work demands thinking about, and using, a storehouse of information firmly

lodged in long term memory. “All-nighter” students can usually recall a lot of terms and

certain “facts,” but can’t do anything with them.

Remember, your thinking and remembering are functions of your brain, and that’s

a biological organ, and significantly, it’s one with limited endurance. In short, it becomes

less efficient the longer you put demands on it without rest. Trying to study 12 hours

without sleep has the same effect on your brain as trying to play basketball for 12 straight

hours would have on the rest of your body.

So, a final rule: “Always get a night of restful sleep the night before an exam.”

Some students are afraid of this rule. They are afraid that sleep will somehow wipe out

all they’ve been studying. But it doesn’t! It’s another of those things that have been

researched and the results are consistent. There is, in fact, a small but significant

increase in the ability to recall or reconstruct when learning is followed by sleep. So if

you want your brain in tip-top condition for an exam (and who wouldn’t?) do your

reviewing in one or two hour periods spread out over several days, and get a real night’s

sleep before the exam.

During the exam

I’ve heard students, going into an exam, say, “I’ve done my part; it’s out of my

hands now.” That idea betrays the erroneous notion that all the hard work is done in

advance, and during the exam you just pour out what you’ve learned. Well, sometimes.

But exams in the tough courses often shock beginning students because they can’t find

much that looks familiar. There’s a reason, and a solution.

Demanding teachers prepare exams that require performance, where performance

is much more than recall. A lot of college instructors produce what might be called

“application questions” for their exams. All that means is that you can’t just write what

you know, you have to use what you know to answer a question or solve a problem that

you haven’t seen before. Only a malicious teacher would question students on material

that had never been discussed, assigned, or included in required reading. It seldom

happens. So when seeing something that looks unfamiliar, convince yourself that it’s

only a question that is asking you to apply something you already know. So it is that

16

concentration and focused thinking are often just as necessary during an exam as before

it. If you have learned well, and reviewed properly, you can be confident that you have

the necessary knowledge. I just takes some hard thinking to see how it applies to a

particular question.

11

Leamnson

A Summary

No one learns unless they want to. I have assumed here that you do. But learning

is a biological process that relies on the brain, a physiological organ that demands the

same maintenance the rest of you does. Don’t abuse it. The best ways to learn have

already been discovered, there’s no need for you to rediscover them by making a lot of

old mistakes all over again. So it is that what you read here might be disappointing.

Instead of new tricks or clever ways to beat the system, it says learning is the only way,

and that learning is difficult and requires effort. But we do know how to do it, and when

it’s done right, it is marvelously satisfying.

I wish all readers of these pages the best of luck in their college days. But as I do

so, I’m reminded of the words of the biologist Pasteur who said, “Chance favors the

prepared mind.”

Robert Leamnson

Dartmouth MA Dec. 2002

This document may be down loaded, printed, and copied, but may not be sold for profit.

The author’s name may not be removed from the document.

rleamnson@umassd.edu

12

17

Fine Arts

2013 Summer Assignment

AP 3-D Studio Art

Mr. Manley

Polk District Schools List of AP Studio Art Summer Assignments

Students will select four concentrations, or series, to explore from this list and complete thumbnail sketches in their

visual journals during summer vacation. These assignments will prepare students to enter AP Studio Art Courses.

Please complete five thumbnail sketches (2-3 inches in size), shaded with value, of 3D forms for each of your four

concentrations. You must pick four concentrations for a total of twenty thumbnail sketches. Please label/title each of

the four concentrations. See example.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

Unusual Interiors and/or Exteriors

Something not There

Artists and/or Concepts Research

Negative Space

Letters as Art

Organic and/or Inorganic

Natural and/or Mechanical Forms

Sequence and/or Transformation

Mini-Concentrations Using the Principles of

Design

Simplify and/or Reorganize

A Sign of the Times

Identity

Social Justice

Within and/or Without

Suspension

Light and/or Shadow

Reflections

Structures/architecture

Magnify and/or Minimize

Exits and/or Entrances

Realistic forms that blend into abstractions

Pottery that alludes to human or animal forms

Modular forms

Defying gravity

Concentration of your own

1

2

M

e

r

e

t

e

R

a

s

m

3u

Ms

s

e

re

en

M

e

r

e

t

e

R

a

s

m

u

s

s

e

n

t

e

R

a

s

m

u

s

s

e

n

5

M

e

r

e

t

e

R

a

s

m

u

s

4

M

e

r

e

t

e

R

a

s

m

u

s

s

e

n

18

Mathematics

2013 Summer Assignment

AP Calculus

Mrs. Haskell

Since AP Calculus (AB) is the equivalent to Calculus 1 in college, we have many concepts to cover to

make sure you are prepared to pass the AP test next May and receive the college credit. With this in

mind, you will need to complete three summer review worksheets. These reviews have been designed

to help you refresh (and possibly learn) basic concepts necessary for success in AP Calculus. It is

imperative that you complete these reviews; they will be graded and will represent the first grades you

receive for 1st quarter.

Below you will find the schedule for submitting the review worksheets:

Worksheet # 1 – Due July 1st

Worksheet # 2 – Due July 25th

Worksheet # 3 – Due the first day of class

You will need to mail, scan-and-email, (or hand deliver) worksheets #1 and #2 by their due dates to:

Jamie Haskell

237 Sunset Court

Davenport, FL 33837

Jamie.haskell@polk-fl.net

I will then check your work and email you if serious corrections are needed. Otherwise they will be

returned to you, graded, on the first day of school. Take these seriously, they will count toward your 1st

quarter grade!

DON’T PROCRASTINATE!

Do a little each day and feel free to look back on your old notes, use the internet, or contact me for help

with tough questions. Email or Facebook are the best options for getting ahold of me during the

summer; I will check them several times each week.

I hope you’re having a fantastic summer!!!!!!

Enjoy it and rest up while you can because you’re

going to be working your butts off for me next year.

19

AP Calculus Worksheet #1

You must know these values just as well as you know the multiplication tables. Remember to consider

what quadrant each angle is located in and if that will cause a negative answer or not. Give exact

values, not decimal approximations (i.e. not calculator values, use the TVT!).

1. sin

tan

2. cos

3

3. tan

6

4

4. sin

5.

6

3

= _____

6. cos 0

cos

7. cos

3

2

= _____

11. tan

= _____

6

= _____

8. sin

2

= _____

= _____

3

2

= _____

12. cos

= _____

13. tan

2

= _____

9. cos

3

10.

= _____

14. cos

4

15. sin

0

16. tan

= _____

= _____

3

2

17. sin

= _____

= _____

= _____

= _____

18. sin

4

= _____

19. sin

2

20. tan

0

= _____

= _____

= _____

20

21. tan

csc

22. csc

19

6

= _____

= _____

13

4

23. cot

= _____

9

2

24. sec 7

= _____

= _____

25.

See if you can still graph the following basic graphs without using a calculator or the internet. You’ll

need to know them very, VERY well. Please give the Domain, Range, and a sketch of each, showing

asymptotes when appropriate:

26. y x 2

27. y x 3

28. y x

D:

D:

D:

R:

R:

R:

29. y ln( x )

30. y e x

31. y

D:

D:

D:

R:

R:

R:

x

21

32. y x

33. y

D:

D:

R:

R:

34. y sin( x)

1

x

35. y cos(x)

36. y tan( x )

D:

D:

D:

R:

R:

R:

You should be able to expand binomials (meaning, multiply them) quickly and easily. Please box the

simplified expansions of the following:

37. ( x 3) 2

38. ( x 3) 2

(If you get x 2 9 please look again!)

39. ( x 2)3

40. ( x 2)3

22

AP Calculus Worksheet #2

You need to be able to deal with inequalities as well. Write your answers in interval notation (you can

use a number line to check your answer).

42. Find the solution interval: x 6 3

41. Find the solution interval: x 2 9

And you have to be able to think!

43. Which of the following is always correct if a b ? For the false choices, give a counter-example.

(Hint: try using real numbers for a and b in each of the situations, and don’t forget to try negative

numbers)

(a) a 3 b 3

(b) a b

(d) 6a 6b

(e) a 2 ab

(c) 3 a 3 b

(f) a 3 a 2b

For #44—47 consider a line connecting two points: (-3, 7) (5, 9)

44. Find the slope of the line

45. Write the equation of the line in Point-Slope Form

23

46. Find the distance between the points:

Distance = _____

47. Find the midpoint between the points:

Midpoint =

(

,

)

Now let’s see if you remember how to tell the ways a graph has shifted just by looking at its equation:

48. Write the equation of the vertical asymptote(s) for y 2

5

x4

49. Write the equation of the horizontal asymptote(s) for y 2

5

x4

50. Normally y sin( x) can only have answers that fall in the Range of [-1, 1], how does that change if

the amplitude is changed to y 5 sin( x ) ?

51. List all reflections, stretches, and shifts that have occurred to the parent graph of the following

equation?

y 3Ln( x 4) 2

Reflected over the:

Stretched vertically/horizontally by a factor of:

Shifted up/down/left/right:

24

And finally, use the given graph to find the following limits:

52. Find

lim = _____

x 3

53. Find

lim = _____

x 2

54. Find

4

2

3

lim = _____

x

25

AP Calculus Worksheet #3

Here we go again, get ready for some refreshments!

The postmark deadline for this review is July 25th

Some more expansions!

But with symbols rather than numbers. Please box your final simplified expansion and FYI: “ x ”is one

symbol. If you don’t like it, change it to “y” and change it back in your final expansion.

1. ( x x)2

2. ( x x)3

3. ( x h) 2

4. ( x h) 3

5. Find the inverse of f ( x )

3

1

x2

6. Given f(x) and g(x), find f(g(2))

1

𝑓(𝑥) = 𝑥

𝑔(𝑥) =

1

√𝑥+2

26

For # 7—11, solve for real values of x. Keep in mind, you can simply use a graphing calculator to solve

these quickly…………if you remember how.

7. x 3 3 x

8.

( x 5) 2 x 5

9.

6x 7 3 2x

10. x 3 3 x 2 4 x 12 0

(try synthetic division by choosing a factor of 12 to go in the

“box”)

3

2

11. x 3x 3x 1 0

(you might notice a similarity with your expansion to #4)

27

For # 12—15, use y 3 x

12. For what value of x does y = 7?

______

13. For what value of x does y = 0? ______

14. What is the domain of this function? ____________ 15. What is the range of this function? ______

For # 16—23, are the following statements True or False? Ask yourself if the two sides are equivalent.

Analyze both sides and try to figure out what I did; was it a legal operation?

16.

3r

r

3s t s t

20. 4

4

a 4a

b b

17.

21. 4

1

1 1

pq p q

a 4a

b 4b

22. 4

18.

x y x y

5

5 5

a b 4a b

c

c

19. 4

a a

b 4b

23.

a b 4a 4b

c

c

For #24—28, solve for all real values of x. Keep an eye out for extraneous solutions.

24. 3 log 8 x 6

25. 2 ln( x 4) 1

x

26. 7 2e 21

28

1

27. ln x ln( 4 x) ln( 16)

x

28. e 5 4

For 29—30, find all possible values of x over the given interval

29. sin x

3

2

0 x 4

30. cot x 1

0 x 2

For #31—33, reduce the power

(check your Pre-Calculus notes for the “Power Reducing Identities” from section 5.4)

31. sin 2 8 x

32. 2 sin x cos 2 3x

29

33. 5 sin 3 2 x

34. Is f ( x) ( x 2) 3 a 1 – 1 function? Prove your answer algebraically.

𝜋

35. Graph 𝑓(𝑥) = 2𝑠𝑖𝑛 (𝑥 − 4 ) + 1 on the interval 0 ≤ 𝑥 ≤ 2𝜋

Then name its

a) Amplitude:

b) Period:

c) Reflection(s) over the:

d) Shifts:

Determine if #36—37 are Even, odd, or neither? Then use that knowledge to state their symmetry.

36. 𝑦 = 1 − 𝑐𝑜𝑠𝑥

37. 𝑦 = 𝑥 2 + 1

30

Well, the good news is that you can just bring this

one with you to our very first class!

1. Write an equation for the line through (2, 3) and (4, -5) in slope-intercept form and box your

answer.

2. Determine the domain and range of y = 3x - 2. Write your answers in interval notation.

D:

R:

3. Graph the piecewise function, then state its domain and range.

−𝑥 + 1

𝑓(𝑥) = {−𝑥 + 2

𝑥2

𝑥<1

1≤𝑥≤2

2<𝑥

Domain:

Range:

For #4—7, factor each of the quadratics.

4. x 2 11x 24

5. 3 x 2 12 x 12

31

6. 4 x 2 6 x 18

7. 9 x 2 25

8. Categorize the indicated x-values as being “continuous,” a “removable discontinuity,” or a “nonremovable discontinuity.”

x = -3

x = -1

x=0

x=5

3

1

5

9. Now, let’s test your memory of the Trig.Value Table. Try to fill in as much of it as possible from

memory. I am trusting you to be honest with how much you can actually remember. Don’t worry, this

part of the worksheet will not be graded, but should still be done! It’s just practice to see how much of

the table you still have memorized, so you’ll know what parts you need to practice. Who knows, there

may be a quiz on it the first week of school!!! (*wink wink*)

Sin(x)

Cos(x)

Tan(x)

Csc(x)

Sec(x)

Cot(x)

0

𝝅

𝟔

𝝅

𝟒

𝝅

𝟑

32

𝝅

𝟐

Match each of the graphs to its equation. It is important that you are able to do this without a

calculator or other graphing resource:

10. f ( x) x 1

11. f ( x) x 1

f ( x) x 2 1 14. f ( x) ( x 2) 3

f ( x) x 3 1

12. f ( x) x 2 1

13.

15. f ( x) ( x 2) 3

16.

17. f ( x) ( x 1) 3

18. f ( x) e x 3 2

19. f ( x) e x 3 2

20. f ( x) e x 1

21. f ( x) e x 1

22. f ( x)

23. f ( x) x 1 2

24. f ( x)

x 5

25.

27. f ( x) ( x 1) 2

28. f ( x) ( x 2) 2

29.

31. f ( x) ln( x)

32. f ( x) ln( x 1)

33.

x 1 2

f ( x) x 5

26. f ( x) ( x 1) 2

f ( x) ( x 2)

30. f ( x) ln( x)

f ( x) ln( x 1)

1

34. f ( x )

x 1

2

____

35. f ( x)

1

x 1

36. f ( x)

____

[-6, 6] , [-4, 4]

____

37. f ( x)

[-6, 6] , [-4, 4]

[-6, 6] , [-4, 4]

____

[-6, 6] , [-4, 4]

[-6, 6] , [-4, 4]

1

x 1

____

____

____

1

x 1

____

[-6, 6] , [-4, 4]

____

33

[-6, 6] , [-4, 4]

[-6, 6] , [-4, 4]

[-6, 6] , [-4, 4]

____

____

[-6, 6] , [-4, 4]

[-6, 6] , [-4, 4]

____

____

[-6, 6] , [-4, 4]

____

[-6, 6] , [-4, 4]

34

Social Sciences

2013 Summer Assignment

AP European History

Mr. Gompper

Welcome everyone! I hope that you are as excited for the upcoming year as I am. I look

forward to a challenging and hopefully rewarding year.

Over the summer you will be asked to read the book, The Diary of a Napoleonic Foot Soldier by

Jakob Walter. If you wish to purchase the book yourself the cheapest place to find it is Amazon.com

(http://www.amazon.com/Diary-Napoleonic-FootSoldier/dp/0140165592/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&s=books&qid=1303848469&sr=1-1) or you may borrow a

book from me through the front office over the summer. Just make sure to sign it out so that I can track

their location. These books are a first come first serve basis and once they are gone they are gone. Your

assignment will be to answer each question listed below. In addition, I would like you to list and

define any new vocabulary that you may have come across in the reading. The purpose of this paper is

to gauge your grasp of writing and organization using historical information. This will provide me with

knowledge of what you know and what we need to work on.

I would like your paper to be typed, double spaced, size 12 Times New Roman font, and with 1

inch margins all the way around the edges.

Your paper will be due the SECOND DAY OF CLASS just in case you were to forget to bring it

over summer. If you finish your paper early please feel free to email it to me at joshua.gompper@polkfl.net

I look forward to meeting all of you in the fall!

The Diary of a Napoleonic Foot Soldier by Jakob Walter

Introduction

o Did you learn anything new from this introduction?

Campaign of 1806 – 1807

o How did soldiers behave during the course of the war? Provide examples from the text.

o Does the organization and discipline of the army in Walter’s time resemble that of

armies today? Explain your answer.

Campaign of 1809

o What sort of relationship did Jakob have with his brother? Justify your answer with

examples.

o Briefly compare and contrast the campaigns of 1806-1807 to that of 1809.

35

Campaign of 1812 – 1813

o Try to explain Jakob’s and other soldiers pre-occupation with finding and consuming

alcohol. Why is it such a central story line in his diary?

o Why do you think the images dealing with obtaining food and supplies show ease and

abundance while the diary depicts an opposing viewpoint? Which of the two are you

more inclined to believe? Why?

o Describe the Grand Armee’s retreat from Moscow in your own words.

Book Summary

o “An army marches on its stomach.”

- Napoleon Bonaparte

o Do you think this quote is true and discuss how it is portrayed throughout the diary of

Jakob Walter.

36

2013 Summer Assignment

AP Psychology

Ms. Gehlsen

margaret.gehlsen@polk-fl.net

The following assignment will be due the second week of the 2013-2014 school

year (the week of September 2-6).

Your summer assignment is going to involve a bit of research into the general

perspectives in psychology and its history.

You will need to write a brief description of each of the following people or terms

/ perspectives. Brief, would be a decent paragraph demonstrating that you have a

general knowledge of what or whom you are referring to.

1. What is psychology???

2. The contributions of both Wilhelm Wundt and G. Stanley Hall in the birth of

psychology as a new science.

3. The debut of behaviorism and the contribution of John Watson. In this

paragraph, you must demonstrate knowledge of what behaviorism is….and

John Watson’s contribution.

4. Psychoanalytic approach and Sigmund Freud.

5. Ivan Pavlov and his research on classical conditioning. (just basic

information on Pavlov and a brief description of how he “discovered”

classical conditioning.)

6. B.F. Skinner and his research on operant conditioning. (same as above…)

7. The humanist approach to psychology.

8. The debate of nature vs. Nurture.

37

2013 Summer Assignment

AP United States History

Ms. Goble or Ms. Love

We are both excited to have you in one of our AP U.S. History classes for school year 2013-2014. But to

get a head start we’d like you to create some study aides that we will use and add to throughout the

school year.

1. Presidents: on a note card you will write the name of the president, dates of their presidency,

political party, and the name(s) of their vice presidents. So for example:

George Washington

1789 – 1797

Federalist Party

Vice President John Adams

Need a listing of the presidents? Check out:

http://www.enchantedlearning.com/history/us/pres/list.shtml

2. Vocabulary: there are quite a few terms that you will need to learn for the AP exam. We would

like for you to create notecards for each of the following vocabulary. After writing the

vocabulary word on one side, write a one to two sentence definition on the other side, but leave

some room to add additional notes from class.

38

Spanish America

1. Christopher Columbus

2. Hernando Cortes

Colonial America

1. Jamestown

2. Capt. John Smith

3. Plymouth Colony

4. Pilgrims

5. Puritans

6. Mayflower Compact

7. MA Bay Colony

8. John Winthrop

9. “City upon a Hill”

10. VA House of Burgesses

11. Proprietorship

12. George Calvert

Revolutionary America

1. Proclamation of 1763

2. Stamp Act 1765

3. Stamp Act Congress

4. Declaratory Act 1766

5. Boston Massacre 1770

6. Crispus Attucks

7. Intolerable (Coercive) Acts

8. Articles of Confederation

9. Lexington and Concord

10. French Alliance 1778

11. Treaty of Paris 1783

12. Northwest Ordinance of 1787

The Constitution and Early Republic

1. Constitutional Convention 1787

2. Virginia Plan

3. Connecticut Plan

4. Anti-Federalists

5. Jay Treaty 1794

6. Washington’s Farewell Address 1796

7. John Adams

8. Strict/Loose Construction

9. Republican Motherhood

Jefferson, Madison, Monroe

1. Louisiana Purchase

2. Judiciary Act of 1801

3. Marbury v. Madison 1803

4. McCulloch v. Maryland 1819

5. Gibbons v. Ogden 1824

6. Macon’s Bill #2

7. Henry Clay (KY)

8. Hartford Convention 1814

9. “Era of Good Feelings”

10. Adams Onis Treaty 1819

11. Monroe Doctrine (1823)

12. Eli Whitney

13. Denmark Vessey (1822)

3. Montezuma

4. Treaty of Tordesillas

5. Ponce de Leon

13. Act of Toleration (1649)

14. Bacon’s Rebellion

15. Headright System

16. Indentured Servant

17. Antinomianism

18. Roger Williams

19. Anne Hutchinson

20. Quakers

21. William Penn

22. Mercantilism

23. Navigation Acts

24. Triangle Trade

25. Halfway Covenant

26. First Great Awakening

27. Jonathan Edwards

28. Cotton Mather

29. Salem Witch Trials

30. Poor Richard’s Almanac

31. John Peter Zenger, Free Press

32. French and Indian War

33. Albany Plan of Union

34. Treaty of Paris 1763

35. New England Dom/Confed

36. Salutary Neglect

13. Sugar Act 1764

14. Quartering Act 1765

15. Sons of Liberty

16. Townshend Acts

17. Patrick Henry

18. Committees of Correspondence

19. Quebec Act 1774

20. Second Cont. Congress 1775

21. Olive Branch Petition

22. Loyalists (Tories)

23. Shay’s Rebellion

24. Richard Henry Lee

25. Virtual Representation

26. Virginia Resolves

27. Writs of Assistance

28. Samuel Adams

29. John Dickinson

30. Boston Tea Party 1773

31. First Cont. Congress 1774

32. Common Sense

33. Battle of Saratoga

34. Battle of Yorktown 1781

35. Annapolis Convention

36. Declaration of Independence

10. James Madison

11. New Jersey Plan

12. 3/5 Compromise

13. Federalist Papers (#10 esp.)

14. Whiskey Rebellion 1794

15. Democratic Republican Party

16. Alien and Sedition Acts

17. “Citizen” Genet

18. Pinckney’s Treaty

19. Alexander Hamilton

20. Thomas Jefferson

21. Federalists

22. Judiciary Act of 1789

23. George Washington

24. XYZ Affair

25. VA and KY Resolutions 1799

26. Revolution of 1800

14. Lewis and Clark

15. “Midnight Judges”

16. John Marshall

17. Dartmouth v. Woodward 1819

18. Aaron Burr

19. War Hawks

20. War of 1812

21. Treaty of Ghent 1814

22. Tariff of 1816

23. Panic of 1819

24. Erie Canal

25. Samuel Slater

26. James Monroe

27. Sacajawea

28. Judicial Review

29. Fletcher v. Peck 1810

30. Cohens v. Virginia 1821

31. Embargo Act 1807

32. John C. Calhoun (SC)

33. Impressments

34. Battle of New Orleans

35. Rush Bagot Agreement

36. Missouri Compromise (1820)

37. Robert Fulton

38. Lowell Factory Girls/System

39

2013 Summer Assignment

AP World History

Mr. Gompper or Mrs. Tillmannshofer

Welcome everyone! We hope that you are as excited for the upcoming year as we are. We look

forward to a challenging and hopefully rewarding year.

Over the summer you will be asked to read the book, A History of the World in Six Glasses, written

by Tom Standage. If you wish to purchase the book yourself the cheapest place to find it is Amazon.com

(http://www.amazon.com/History-World-6Glasses/dp/0802715524/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1302699988&sr=1-1) or you may borrow a

book from us through the front office over the summer. Just make sure to sign it out so that we can track

their location. These books are on a first come first serve basis and once they are gone they are gone.

Your assignment will be to answer ONE question about each topic and then write a generic summary and

reflection. The purpose of this paper is to gauge your grasp of writing and organization using historical

information. This will provide us with knowledge of what you know and what we need to work on.

We would like your paper to be typed, double spaced, size 12 Times New Roman font, and with 1

inch margins all the way around the edges.

Your paper will be due the SECOND DAY OF CLASS just in case you were to forget to bring it over

summer. If you finish your paper early please feel free to email it to us at

joshua.gompper@polk-fl.net

tara.tillmannshofer@polk-fl.net

We look forward to meeting all of you in the fall!

A History of the World in Six Glasses – Tom Standage

Beer in Mesopotamia and Egypt

o Describe the creation process of the world’s first beer.

o Explain the roles beer played in social gatherings. Do any traditions survive today?

o Compare and contrast the use of and value of beer in Mesopotamia and Egypt.

Wine in Greece and Rome