prism aff - um2015 camp

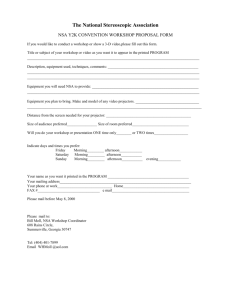

advertisement