Jan.22_Best Practices in Content Reading.Wiki

advertisement

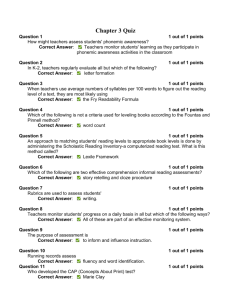

Best Practices in Content Reading TEACHING A THINKING APPROACH FOR READING COMPREHENSION A Presentation by Dea Conrad-Curry Your Partner in Education www.partnerinedu.com dconrad@ilstu.edu NAME ______________________ TEXT ______________________ PAGES _______ DATE _______ Admit Before the session begins, circle the best answer. Yes No Not Sure Yes No Not Sure Yes No Not Sure Yes No Not Sure Yes No Not Sure Admit & Exit Slip Exit At the session’s end, circle the best answer. 1. The reading process is the same whether reading a newspaper, a novel, a biology book, or a historical analysis. Notes__________________________________ Yes 2. The same reading strategies can be used in all types of print text. Notes___________________________________ Yes 3. Graphic organizers are tools to help students understand the comprehension process and as such are means to an end and not an end in themselves. Notes___________________________________ Yes 4. Reading comprehension is based more on what the reader bring to the text than what the author provides in the text. Notes___________________________________ Yes 5. Group activities are not beneficial to improving reading comprehension because reading is a solitary act of listening to one’s inner voice and blocking out distraction. Yes No Not Sure No Not Sure No Not Sure No Not Sure No Not Sure Notes___________________________________ Yes No Not Sure 6. Teaching students appropriate highlighting skills is goal of active reading. Notes___________________________________ © 2009 Partner in Education Yes No Not Sure 2 What is Reading? to understand the meaning and grasp the full sense of (such mental formulations) either with or without vocal reproduction to go over or become acquainted with or get through the contents of (as a book, magazine, newspaper, letter) by reading : PERUSE to have such knowledge of …as to be able to read with full understanding From Merriam Webster Unabridged Dictionary http://unabridged.merriam-webster.com/cgibin/unabridged-tb?book=Third&va=Reading © 2010 Partner in Education 3 Neuroscience informs Reading instruction THE BRAIN SEEKS UNDERSTANDING BY CONNECTING NOVEL OR NEW INPUT TO EXISTING KNOWLEDGE Reading Strategies or Skills? Predicting Self-monitoring Confirming Elaborating Connecting Reflecting Summarizing Inferring Visualizing Questioning QAR Self Questioning Surveying Activating Prior Knowledge Identifying Key Words Clarifying Rereading Finding & Using Context Clues Restating Drawing Conclusions Setting a Purpose Evaluating Skimming/Scanning Think Aloud © 2010 Partner in Education 5 The Inner Conversation Teaching students through “think aloud” modeling to become aware of their thinking as they read monitor their understanding and keep track of meaning listen to the voice in their head notice when they stray away from thinking about the text notice when meaning making breaks down detect obstacles to understanding understand and be able to select a strategy that will help repair meaning , maintain meaning, and further understanding © 2010 Partner in Education 6 What process does your brain follow in order to determine whether it can identify the meaning of the word “rouge”? Fast Mapping & Extended Mapping (Carey 1978) © 2010 Partner in Education 7 What process is your brain following in determining the meaning of the word “amis”? © 2010 Partner in Education 8 © 2010 Partner in Education 9 Productive Thinking: 3-Part Activity Step 1 Step 2 In my Head Generate a list of as many ideas pertaining to a prompt—no idea is a bad idea Aim for 12- 15 ideas as students become more proficient with the process Keep in mind some topics may limit or extend the possibilities Set a time limit for the thought process—1 minute to 1 ½ minutes Step 3 With a Partner Whole Class Designate the spokesperson of the partner (or threesome) Since the goal is 1215, steal good ideas from your partner’s list Turn to a neighbor & share ideas Continue to come up with more ideas, even those that were not on the original lists Set a time limit for the sharing process: 2 minutes Each group chooses through consensus one idea to share with the entire class Shared idea should show the best thinking: uniqueness counts Continue to steal ideas as groups share, always aiming to lengthen the list © 2010 Partner in Education 10 HOW COULD I USE THIS STRATEGY IN MY CLASSROOM? © 2010 Partner in Education 11 SHIFTING FROM IMAGES TO PRINT TEXT Think about and note what processes your brain follows as we read this next text together? © 2010 Partner in Education 12 JABBERWOCKY by Lewis Carroll `Twas brillig, and the slithy toves Did gyre and gimble in the wabe: All mimsy were the borogoves, And the mome raths outgrabe. One, two! One, two! And through and through The vorpal blade went snickersnack! He left it dead, and with its head He went galumphing back. "Beware the Jabberwock, my son! The jaws that bite, the claws that catch! Beware the Jubjub bird, and shun The frumious Bandersnatch!" He took his vorpal sword in hand: Long time the manxome foe he sought -So rested he by the Tumtum tree, And stood awhile in thought. And, as in uffish thought he stood, The Jabberwock, with eyes of flame, Came whiffling through the tulgey wood, And burbled as it came! from Lewis Carroll’s Through the LookingGlass and What Alice Found There, 1872. "And, has thou slain the Jabberwock? Come to my arms, my beamish boy! O frabjous day! Callooh! Callay!' He chortled in his joy. `Twas brillig, and the slithy toves Did gyre and gimble in the wabe; All mimsy were the borogoves, And the mome raths outgrabe. © 2010 Partner in Education 13 Original Illustration by Sir John Tenniel First published in Carroll, Lewis. 1871. Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There. © 2010 Partner in Education 14 What were the reading challenges presented by “JABBERWOCKY” Challenges Cognitive Processes © 2010 Partner in Education 15 © 2010 Partner in Education 16 What is Content Reading? Reading characterized by factual information conveyed using multisyllabic technical words developed through a combination of organizational structures, for example, cause/effect, compare-contrast, or sequencing. Questions to Ask Students About Reading Strategy Use What is a reading strategy? Before you begin reading a content textbook, what strategies do you put in place? Why do you preview a content textbook? How is reading in language arts or English different than reading in science or social studies? How do you know if you’ve really understood a reading passage in an informational text? What strategies can you use when you encounter a big word and you don’t know what it means? When should you stop and think about what you are reading? What are the clues that make you realize that time has come to stop and think? © 2010 Partner in Education 17 Predict Connect Visualize © 2010 Partner in Education 18 Content Reading vs. Fiction Reading (Rosenblatt, [1938], 1966) Efferent Aesthetic Reading purpose Reading purpose to take away pieces of information Reading Process reading in “fits and starts” staring and stopping to take notes and reflect annotations helpful Content overwhelming with new information to be “taken away” Reading Process reading with speed and anticipation stopping to take notes only as a support mechanism Content engaging the reader to join with the text; connection building © 2010 Partner in Education 19 Efferent Reading: Purposes Overview of material Summarizing Uses skimming skills Identifies key words Reads titles & headings Finds topic sentences Delete redundancy Delete trivia Find / invent topic sentence Create superordinates Finding the Main Idea Synthesize & Evaluate Identify text structure Delineate supporting ideas Show connections Awareness of implicit & explicit ideas Uses inferential skills Apply information regarding fact & opinion Examine causal relationships © 2010 Partner in Education 20 Why do middle & high school content area teachers need to teach reading skills? Most students do not have reading proficiency levels adequate to be successful in workplace training or institutions of higher education Even colleges and universities like Harvard are discovering their students do not have the prerequisite skills to be successful in an enviornment of high learning. Interrogating Texts: Harvard University Student Guide to Content Reading http://hcl.harvard.edu/research/guides/lamont_hando uts/interrogatingtexts.html © 2010 Partner in Education 21 TEACHING A THINKING PROCESS APPROACH TO READING COMPREHENSION © 2010 Partner in Education 22 The Thinking Process Approach Research Base Cathy Collins Block (2003) John Mangieri Comprehension Lessons must be cognitively rich socially structured pedagogically sound Comprehension as a thought process is ever-changing interactive Moves beyond strategy-based instruction © 2010 Partner in Education 23 The Thinking Process Approach Empowers Students To making meaning for themselves To verbalize when and where they choose to use one or more thinking processes to make meaning To select the appropriate thinking process or combine thinking processes to infer, summarize, predict, etc. Differentiate instruction to provide a broad set of tools for meaning making Source: Block, Cathy Collins. (2006). “The Thinking Approach to Comprehension Development.” Improving Comprehension Instruction. p 56. © 2010 Partner in Education 24 4-Step Sequential Process Step One: Teacher Think Aloud (Davey, 1983) with first strategy Students watch while teacher models how use the first strategy, coding the text and talking aloud. Step Two: Teacher Think Aloud with second strategy Students watch while teacher models how to use the second strategy, coding and talking aloud Step Three: Shared Thinking Teachers and students work together to identify and relate their use of the first strategy Block suggests four practices Step Four: Flexible Group Students work together using comprehension process and set goals for further learning Research Base: Block, Cathy Collins. (2006). “The Thinking Approach to Comprehension Development.” Improving Comprehension Instruction. © 2010 Partner in Education 25 Questioning & Connecting Natural Cognitive Strategies Using cognitive strategies with content images © 2010 Partner in Education 26 Think – Pair – Share Why does one ask questions? © 2010 Partner in Education 27 Step One: Teacher Think Aloud © 2010 Partner in Education 28 Washington Crossing the Delaware © 2010 Partner in Education 29 Using Connections to Answer Questions © 2010 Partner in Education 30 Connecting Concept & Image Text to Self Washington Crossing the Delaware Text to World Text to Text © 2010 Partner in Education 31 Step Two: Shared Reading © 2010 Partner in Education 32 Shared Thinking (Reading) with Images © 2010 Partner in Education Connecting Concept & Image Text to Self Photosynthesis & the Food Chain Text to World Text to Text © 2010 Partner in Education 4-Stages of Instruction Comprehension vs. Decoding If students are reading at instructional level 75-85% of the day, reading comprehension goes up. If students are reading at a frustrating level most of the day, they are only decoding. In order to learn and retain content material, they must be comprehending the text, not merely reading the words. • Teacher • Model • Teacher & Student • Guided • Student & Student • Facilitated • Student • Independent © 2010 Partner in Education 35 Step Three: Flexible Grouping © 2010 Partner in Education 36 Text Word/s / Picture/s Directions: First, list questions that your brain asks when looking at this cartoon. Next, choose one question and see if you can figure out the answer on your own. Makes me ask… Causes me to remember Generate five questions related to the political cartoon. 1. ________________________________________ 2. ________________________________________ Because of this connection, I answer 3. ________________________________________ 4. ________________________________________ 5. ________________________________________ © 2010 Partner in Education p.37 Directions:First, list questions that your brain asks when looking at this cartoon. Next, choose one question and see if you can figure out the answer on your own. Text Word/s / Picture/s Makes me ask… Causes me to remember Generate five questions related to the figure above. 1. ________________________________________ 2. ________________________________________ 3. ________________________________________ Because of this connection, I answer 4. ________________________________________ 5. ________________________________________ © 2010 Partner in Education p.38 Active Reading: Marking the Text Connecting Codes © 2010 Partner in Education 39 NAME ____________________________ TEXT ______________________ PAGE _____ DATE ________ Question / Connection Relationship Self-question Your Answer Explain Your Connection Background Knowledge + New Information Who_________________ ____________________? What ________________ ____________________? When ________________ ____________________? Why _________________ ____________________? How _________________ ____________________? Where _______________ ____________________? © 2010 Partner in Education Name: ________________________________________ Date: ________________________ Using Connections to Ask and Answer Questions Text Word/s / Picture/s Text Word/s / Picture/s Text Word/s / Picture/s Makes me ask… Makes me ask… Makes me ask… Causes me to remember Causes me to remember Causes me to remember Because of this connection, I answer Because of this connection, I answer… Because of this connection, I answer… © 2010 Partner in Education Connect to Question & Answer Intermediate Organizer Connecting: Group Interdependence Group Members ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ Directions: You will be given 5 minutes to read the selection alone. Use active reading strategies and be prepared to make two text connections with your group. Groups will meet for 10 minutes to share their understanding of the text and their connections. Record one another’s connections here and discuss which connection/s help you understand the text better. Code your responses and be ready to discuss them with the class. Text to ________ Text to ________ Text to ________ Text to ________ Text to ________ Text to ________ © 2010 Partner in Education 42 42 Step Four: Independent Accountability © 2010 Partner in Education 43 Effective Comprehension Instruction is Socially Structured © 2010 Partner in Education 44 Lesson Materials Presented Sequentially Graphics: photos, artwork, picture books • Connect to self, world, and other texts • Develop questions from those connections • Use connections to answer questions: right there, author and me, on my own Engaging Text: magazine, internet, newspaper • Connect to self, world, and other texts • Develop questions from those connections • Use connections to answer questions: right there, author and me, on my own Content Text: trade books, textbooks, reference • Connect to self, world, and other texts • Develop questions from those connections • Use connections to answer questions: right there, author and me, on my own © 2010 Partner in Education 45 5-Step Sequential Process Step One: Teacher Think Aloud with first strategy Students watch while teacher models how use the fist strategy, coding the text and talking aloud. Step Two: Shared Thinking Teachers and students work through the first strategy together Step Three: Teacher Think Aloud with second strategy and incorporates the first strategy as necessary Students watch while teacher codes and talks aloud, modeling how the strategies work together Block suggests teacher provide 3 think alouds of strategies in tandem Step Four: Shared Thinking Students work together using comprehension process and set goals for further learning Step Five: Flexible Groups Research Base: Block, Cathy Collins. (2006). “The Thinking Approach to Comprehension Development.” Improving Comprehension Instruction. © 2010 Partner in Education 46 Monitoring Questions Raising the bar on student thinking by teaching selfmonitoring strategies © 2010 Partner in Education 47 Question Answer Relationship, Raphael (1986) In the text In my head Right There Author and Me Think and Search On my Own © 2010 Partner in Education 48 Source of Half Earth's Oxygen Gets Little Credit by John Roach for National Geographic News June 7, 2004 Fish, whales, dolphins, crabs, seabirds, and just about everything else that makes a living in or off of the oceans owe their existence to phytoplankton, one celled plants that live at the ocean surface. Phytoplankton are at the base of what scientists refer to as oceanic biological productivity, the ability of a water body to support life such as plants, fish, and wildlife. "A measure of productivity is the net amount of carbon dioxide taken up by phytoplankton," said Jorge Sarmiento, a professor of atmospheric and ocean sciences at Princeton University in New Jersey. The one-celled plants use energy from the sun to convert carbon dioxide and nutrients into complex organic compounds, which form new plant material. This process, known as photosynthesis, is how phytoplankton grow. Herbivorous marine creatures eat the phytoplankton. Carnivores, in turn, eat the herbivores, and so on up the food chain to the top predators like killer whales and sharks. But how does the ocean supply the nutrients that phytoplankton need to survive and to support everything else that makes a living in or off the ocean? Details surrounding that answer are precisely what Sarmiento hopes to learn. Retrieved from: http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/ 2004/06/0607_040607_phytoplankton.html © 2010 Partner in Education 49 Robert Frouin, a research meteorologist with the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, California, said understanding the process by which phytoplankton obtains ocean nutrients is important to understanding the link between the ocean and global climate. "Marine biogeochemical processes both respond to and influence climate," Frouin said. "A change in phytoplankton abundance and species may result from changes in the physical processes controlling the supply of nutrients and sunlight availability." Oxygen Supply Phytoplankton need two things for photosynthesis and thus their survival: energy from the sun and nutrients from the water. Phytoplankton absorb both across their cell walls. In the process of photosynthesis, phytoplankton release oxygen into the water. Half of the world's oxygen is produced via phytoplankton photosynthesis. The other half is produced via photosynthesis on land by trees, shrubs, grasses, and other plants. As green plants die and fall to the ground or sink to the ocean floor, a small fraction of their organic carbon is buried. It remains there for millions of years after taking the form of substances like oil, coal, and shale. "The oxygen released to the atmosphere when this buried carbon was photosynthesized hundreds of millions of years ago is why we have so much oxygen in the atmosphere today," Sarmiento said. Today phytoplankton and terrestrial green plants maintain a steady balance in the amount of the Earth's atmospheric oxygen, which comprises about 20 percent of the mix of gasses, according to Frouin. A mature forest, for example, takes in carbon dioxide from the atmosphere during photosynthesis and converts it to oxygen to support new growth. But that same forest gives off comparable levels of carbon dioxide when old trees die. © 2010 Partner in Education 50 "On average, then, this mature forest has no net flux of carbon dioxide or oxygen to or from the atmosphere, unless we cut it all down for logging," Sarmiento said. "The ocean works the same way. Most of the photosynthesis is counterbalanced by an equal and opposite amount of respiration." Carbon Sink The forests and oceans are not taking in more carbon dioxide or letting off more oxygen. But human activities such as burning oil and coal to drive our cars and heat our homes are increasing the amount of carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere. Most of the world's scientists agree that these increasing concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere are causing the Earth to warm. Many researchers believe that this phenomenon could lead to potentially catastrophic consequences. Some researchers argue that enriching the oceans with iron would stimulate phytoplankton growth, which in turn would capture excess carbon from the Earth's atmosphere. But many ocean and atmospheric scientists debate whether this would indeed provide a quick fix to the problem of global warming. Research by the Scripps Institution of Oceanography suggests an increase in phytoplankton may actually cause the Earth to grow warmer, due to increased solar absorption. "Our simulations show that by increasing the phytoplankton abundance in the upper oceanic layer, sea surface temperature is increased, as well as air temperature," Frouin said. As Sarmiento notes, phytoplankton obtains most of its carbon dioxide from the oceans, not the atmosphere. "Pretty much all of the carbon dioxide taken up by phytoplankton comes from deep down in the ocean, just like nutrients, where bacteria and other organisms have produced it by respiring the organic matter that sank from the surface," Sarmiento said. © 2010 Partner in Education 51 Name ___________________ Text _________________________ Pages _____ QAR: Question Answer Relationships Right There Adapted from: Raphael, Taffy & Highfield, Kathy & Au, Kathryn H.(2006). QAR Now. NY: Scholastic. In the book Think & Search © 2010 Partner in Education Author & Me In my head On My Own 52 Many, Different Question Types Essential Questions Planning Questions Elaborating Questions Inventive Questions Clarification Questions Probing Questions Irrelevant Questions Divergent Questions Irreverent Questions Telling Questions Hypothetical Questions Provocative Questions Unanswerable Questions Strategic Questions © 2010 Partner in Education 53 Classification: Question Types Convergent Inference Questions Divergent Inference Questions Visualizing Wondering Explorative, but responses fall within a finite range of accuracy Seeks facts/data either within or beyond the text. Explorative with varied and alternative answers Questions Require cognitive & emotional skills to make judgment Clarifying Evaluative Questions Questions Adapted from: Erickson, H.L. (2007). Concept-basead curriculum and instruction for the thinking classroom. © 2009 Partner in Education Active Reading & Coding © 2010 Partner in Education 55 Finding the Main Idea Using Questioning and Connecting Strategies to Find the Main Idea © 2010 Partner in Education 56 Finding the Main Idea Uncover indications of what an author considers crucial; what is expected of you to glean from the argument Examine the language chosen or used to be alert you to ideological positions, hidden agendas or biases. Watching for recurring images Be aware of repeated words, phrases Synthesize in your understanding the types of examples or illustrations used Be sensitive to consistent ways of characterizing people, events, or issues Adapted from Interrogating Texts: 6 Reading Habits to Develop in Your First Year at Harvard . © 2010 Partner in Education 57 Rule Strategy: Keep, Delete, Combine Keep Topic sentence—if there is one Transition words: however, but, consequently, resultant Delete unnecessary words or sentences conjunctions, prepositions, personal references, interruptions by the author w/opinion or examples, superfluous descriptors Combine repeated and/or similar words as one reference Substitute words For unfamiliar concepts: vast stretches—large area To categorize: axes, mauls, and hammers are tools Combine kept, substituted, and topic sentence Adapted from: Day, Jeanne D.(1986). Teaching summarization skills: influences of student ability and strategy difficulty. Cognition and Instruction 3(3). 193-210. © 2010 Partner in Education 58 Questioning to Find the Main Idea Before reading Elicit prior knowledge related to the core ideas of the text Make connections between background knowledge and text subject Set a purpose for reading During reading Identify text structure Clarify and review what has happened so far Confirm or create new predictions Evaluate the text critically Compare with other experiences or readings Monitor reading for meaning and accuracy © 2010 Partner in Education 59 Teaching “Cue” or Transition Words Sequence Chronology at first, first of all, to begin with, in the first place, at the same time, for now, the next step, in time, in turn, later on, meanwhile, next, then, soon,, later, while, earlier, afterward, simultaneously Direction here, there, over there, beyond, nearly, opposite, under, above, to the left, to the right, in the distance © 2010 Partner in Education Contrast & Comparison Contrast instead, likewise, on one hand, on the other hand, on the contrary, rather, yet, but, still, similarly, however, nevertheless, in contrast, contrast, by the same token, conversely, instead Similarly likewise, on one hand, on the other hand, on the contrary, rather, similarly, yet, but, however, still, nevertheless Exception besides, except, excepting, excluding, other than, outside of, 60 save Text Structure Narrative Definition lists one or more causes and the resulting effect/s Problem / Solution explains how two or more things are alike and/or how they are different Cause & Effect indentifies category that a concept may belong to and explains why Comparison lists items or events in numerical or chronological order Classification describes a topic by listing characteristics, features, and examples Sequence presents a term, classifies the term, and then explains how that term is like and unlike other concepts within the classification Descriptive a narrative w/i an expository text to clarify, elaborate or link the subject matter to a personal experience states a problem and lists one or more solutions for the problem Question / Answer poses a question and answers it © 2010 Partner in Education 61 Read and Think Aloud Lift the text Make a transparency of the selected text to share with the class Read the text aloud, coding as you go For questioning, just place a ? each time you pause to reflect—teach students how to mark text or use Post-its Reason through the text Pause, physically remove yourself from the text and orally express your thinking Reread a brief but significant text section Model the need to revisit text as you reason Adapted from Harvey, Stephanie & Goudvis, Anne. (2000). Strategy instruction & practice. Strategies that Work. (pp. 27 – 41). Portland: Stenhouse. © 2010 Partner in Education 62 The Chinese and the Transcontinental Railroad By Robert Chugg The Chinese, or Celestials (from the Celestial Empire), as they were often called in the 1800s, have a long history in Western America. Chinese records indicate that Buddhist priests traveled down the west coast from present day British Columbia to Baja California in 450 A.D. Spanish records show that there were Chinese ship builders in lower California between 1541 and 1746. When the first Anglo-Americans arrived in Los Angeles, they found Chinese shopkeepers. However, only a few Chinese were in the America's until gold was discovered in California in 1848. When news of the discovery reached China, many saw this as an opportunity to escape the extreme poverty of the time. Many peasant families were forced to sell one of their children, usually a girl, in order to survive. Paying $40 cash or signing a contract to repay $160 for passage, thousands were packed into ships for the voyage to the Golden Mountain as they called California. Lying on their sides in 18 inches of space, mortality ran as high as 25 percent on some ships. SOURCE: The Brown Quarterly. Vol. 1 (Spring 1997). http://brownvboard.org/brwnqurt/01-3/013f.htm#cap3 © 2010 Partner in Education 63 Unlike most immigrants, the Chinese didn't come to stay. All they wanted was to save $300-400 and then return to China to live a life of wealth and luxury. Three hundred dollars would allow them to marry, have children, a big house, fine clothes, the best foods, servants, and tutors for their children. Opinions were mixed about these newcomers. The rich valued them as workers because they were willing to work for lower wages, were clean, dependable, did as they were told and didn't get drunk and fight at work. The working class feared them as competition for their jobs. Discrimination was rampant. The Chinese could not become citizens, vote, own property, or even testify in court and had to live in certain areas of town and could only work at certain jobs. Life was hard, but by 1865, about 50,000 had come to the Golden Mountain. After the Central Pacific (CP) started building the Transcontinental Railroad eastward from Sacramento, demand for Chinese workers increased greatly. The CP figured they needed 5,000 workers to build the railroad, but the most they ever had just using white workers was about 800. Most of these stayed only long enough for a free trip to the end of the track and then headed for the gold fields. The CP hired all the available Chinese workers and then sent agents to Canton province, Hong Kong, and Macao. SOURCE: The Brown Quarterly. Vol. 1 (Spring 1997). http://brownvboard.org/brwnqurt/013/01-3f.htm#cap3 © 2010 Partner in Education 64 With an average height of 4'10" and weight of 120 lbs., many doubted these men could handle 80 lb. ties and 560 lb. rail sections. But handle them they did, as well as most other construction jobs. So well in fact that by the time they joined the rails at Promontory Summit, Utah on May 10, 1869, more than nine out of ten CP workers, over 11,000 in all where Chinese. Much of the work they did has become legend. Driving through California's Sierra Nevada Mountains, they were faced with solid granite outcroppings. After the CP's imported Cornish miners gave up, the Chinese with pick, shovel and black powder progressed at the rate of 8 inches a day. And this was working 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, from both ends and both ways from a shaft in the middle. The winters spent in the Sierras were some of the worst on record with over 40 feet of snow. Camps and men were swept away by avalanches and those that weren't were buried in drifts. The Chinese had to dig tunnels from their huts to the work tunnels. Many didn't see daylight for months. At Cape Horn in the Sierras, they hung suspended in baskets 2,000 ft. above the American River below them and drilled and blasted a road bed for the railroad without losing a single life (lots of fingers and hands though). After hitting the Nevada desert they averaged more than a mile a day. But working in 120 heat and breathing alkali dust took its toll. Most were bleeding constantly from the lungs. SOURCE: The Brown Quarterly. Vol. 1 (Spring 1997). http://brownvboard.org/brwnqurt/013/01-3f.htm#cap3 © 2010 Partner in Education 65 Even though the CP --realizing how valuable they were-- treated them better than most, they were still not on a par with the whites. A white laborer was paid $35.00 a month plus room and board and supplies. The Chinese were paid $25.00 a month and paid for their own food, supplies, cook and headman. After a strike in the Sierras, where they won the right not to be whipped and beat and another strike in the Nevada desert, they got up to $35.00 a month but still paid for their own supplies. The whites thought the Chinese were strange because of the strange clothes and hats they wore, because they ate strange foods and drank boiled tea all day, spoke in their sing-song language, and most of all, because they washed and put on clean clothes every day. The whites on the other had, drank from the puddles, seldom bathed or put on clean clothes, got drunk and fought and spent their hard-earned money on soiled doves and gambling. In return for the dedication and hard work of the diligent Chinese laborers, an eight man Chinese crew was given the honor of bringing up and placing the last section of rail on May 10th, 1869. A few of the speakers mentioned the invaluable contributions of the Chinese but for the most part, the people of the day ignored them and history has neglected them. Only in the last ten to fifteen years has their story really started to become known. For the thousands who died aboard ship, the hundreds who died in accidents and the thousands who died of small pox it is long past due. Golden Spike National Historic Site in Brigham City, Utah which was established in 1965, commemorates this history. On May 10, 1869, the Union Pacific and Central Pacific Railroads met at Promontory Summit Utah and united the continent with the completion of the nation's first transcontinental railroad. Hence Chinese participation is prominent in what is perhaps the most important event in the history of the western expansion of the country. It linked East to West, opened up vast areas to settlement and provided easy access to new markets. SOURCE: The Brown Quarterly. Vol. 1 (Spring 1997). http://brownvboard.org/brwnqurt/01-3/01-3f.htm#cap3 66 Questioning after reading Reinforce the concept that reading is for understanding the meaning of the text and making connections Model ways of thinking through and organizing the information taken in from reading a text Think critically about the text Respond on a personal level © 2010 Partner in Education 67 Common Content Text Structures Science Compare / Contrast Concept Definition Description Generalization / Principle Process Cause / Effect Thinking Maps Resource: http://www.somers.k12.ny.us/intranet/skil ls/thinkmaps.html Social Science Chronological sequence Comparison & Contrast Concept Definition Description Episode Generalization / Principle Process Cause / Effect © 2010 Partner in Education 68 Provide models for student thinking Using Direct instruction & Facilitated Learning to Teach Strategic Thinking © 2010 Partner in Education 69 The Thinking Process Approach Builds Habits of Mind Applying past knowledge to new situations Precision of language and thought Questioning and posing problems Remaining open to continuous learning Persistence Striving for accuracy Thinking flexibly Thinking interdependently From The Art Costa Center for Thinking. http://www.artcostacentre.com/ Creating, imagining and innovating Metacognition Finding humour Listening with understanding and empathy Responding with wonderment and awe Gathering data through all senses Managing impulsivity Taking responsible risks © 2010 Partner in Education 70 Three Sequential Lesson Types Lesson Type One: Teacher Think Aloud Students watch while teacher models how to use two comprehension strategies simultaneously Lesson Type Two: Shared Reading Teachers and students read together to identify and relate their use of the reading strategies Lesson Type Three: Flexible Group Students work together using comprehension process and set goals for further learning Research Base: Block, Cathy Collins. (2006). “The Thinking Approach to Comprehension Development.” Improving Comprehension Instruction. © 2010 Partner in Education 71 30% Guideline First 30% Teacher reads and thinks aloud Students watch & learn Second 30% Teacher begins the process Students join in to share & practice skills Next 30% Think, Pair, Share Other flexible grouping © 2010 Partner in Education 72 LESSON TYPES & ASPECTS LESSON TYPE LESSON PURPOSE LESSON ASPECTS READ / THINK ALOUD •Introduce new process •Models executive thinking •Makes the invisible thought processes apparent •Teacher has physical text copy •Students have visual text access—but not physical copy •Select students may have physical text copy •Students thoughtfully engaged SHARED READING •Fosters confidence •Fosters collaboration •Acts as informal assessment •Provides guided practice •Teacher displays class copy of text •Students may or may not have physical text coy •Students actively engaged FLEXIBLE GROUPING •Provides scaffolding to independent •Allows for differentiating text •Allows for differentiating lessons •Each student has text copy OR •Group shares text copy •Group task is clearly defined and has been modeled prior to grouping © 2010 Partner in Education 73 Allow for Practice © 2010 Partner in Education 74 M Day 1 T W Day 2 TH Day 3 Introduce first strategy set w/ think aloud Reinforce w/Think aloud followed w/shared Day 6 Introduce second strategy set w/think aloud Day 7 Day 8 Reinforce 50% /50% Reinforce w/shared Practice Day 11 Independent Practice Day 12 Reinforce w/shared Practice Day 13 Independent Practice Independent Practice © 2010 Partner in Education F Day 4 Flexible Grouping Practice Day 9 Flexible Group Practice Day 5 Flexible Group Practice Day 10 Flexible Group Practice Day 14 Assessment of strategy use & content retention 75 References ACT. (2005). Reading Between the Lines: What ACT Reveals About College Readiness in Reading. http://www.act.org/path/policy/pdf/reading_report.pdf Block, Cathy Collins. (2006). “The thinking approach to comprehension development.” Improving Comprehension Instruction. (pp. 54 – 79). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Costa, Art. The Art Costa Center for Thinking. Retrieved 15 Sept. 2007. http://www.artcostacentre.com/ : Day, Jeanne D.(1986). Teaching summarization skills: influences of student ability and strategy difficulty. Cognition and Instruction 3(3). 193-210. Erickson, H.L. (2007). Concept-basead curriculum and instruction for the thinking classroom. Thousand Oaks: Corwin Press. Harvey, Stephanie & Goudvis, Anne. (2000). Strategy instruction & practice. Strategies that Work. (pp. 27 – 41) . Portland: Stenhouse. Harvey, Stephanie & Goudvis, Anne. (2007). Strategies that Work, Second edition. Portland: Stenhouse. Raphael, Taffy & Highfield, Kathy & Au, Kathryn H. (2006). QAR Now. NY: Scholastic. Wright, Jim. The Saavy Teacher’s Guide: Reading Interventions that Work. Retrieved 15 Sept 2007 from http://www.jimwrightonline.com/pdfdocs/brouge/rdngManual.PDF Wiggins, Grant & McTighe, Jay. (2005). Understanding by Design, 2nd Edition. (pp. 84 -45). Alexandria, VA: ASCD. © 2010 Partner in Education 76