The Art of Drama

advertisement

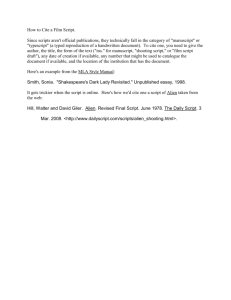

The Art of Drama Drama is the word we use when we want to indicate that we are studying something, like plays or screenplays, in the written form when it is really intended for performance. The written form of the play or film will give important instructions to the director or others involved with the production that may not be apparent to the audience during the performance. Stage Directions In a play, these instructions are called stage directions. They may include; – References to set and props – Directions or actions for actors – Lighting changes In a film, these may include camera angles or changes, as well. Difference Between Drama and Fiction A main difference between drama and fiction is that in drama, the action must be carried out largely by the dialogue and actions of the characters. In fiction, this can be helped along by the narrative point of view. Similarities Between Drama and Fiction There are a number of similarities between drama and fiction: – The settings are equally important and likely to be equally symbolic. – Characters will have the same general functions » In a play, the main character is the protagonist, while the character who opposes the protagonist is the antagonist » The characters will have motivation, or an incentive or reason for their behavior » Sometimes the characters will have a flaw or defect, called hamartia, and that defect will often lead to the character’s downfall. Similarities, continued – Dramas, like works of fiction, will rely heavily on plot to communicate the story and theme. » The common pattern of most dramas is depicted in Freytag’s Pyramid, below Freytag’s Pyramid A German critic, Gustave Freytag, derived his pyramid from Aristotle’s concept of unity. – Basically, a plot will present a problem or conflict that will need to be resolved by its end. – The play provides the audience with needed information in the beginning of the play, generally called exposition, and then increase the dramatic tension with various plot complications. – As the action rises to its climax, the point of highest tension, the audience anticipates the resolution. Another Version of the Pyramid Barbara F. McManus, professor of classics emerita at the College of New Rochelle, has created an alternate diagram of the pyramid. Questions for Analyzing a Plot (Understanding Movies, pages 332-337) What does the exposition include? What are the rising plot points or twists? What, where, or when is the climax? How does the film get resolved? Is that resolution satisfying to viewers? Why or why not? Theatre versus Film Generally speaking, audiences of film need not be as active as audiences in theatre because camera angles and movement, close-ups and long shots, and editing assist film viewers. The actors on film do not interact with audiences, as theatre performers may. For example, in film the elements guide the viewer and help the viewer interpret the information presented. You will not find this in theatre. While the shot above acts as an establishing shot, it is a cluttered image. Lucas uses increasing close-ups to draw viewers’ attentions to the important information. The Auteur Theory in Film In the mid-1950s, the auteur (French for author) theory became popular. It stressed the dominance of the director in film art It holds that whoever is responsible for the mise en scène—the medium of the story—is the true “author” of the story. The Role of Director The talent of the director is still what can “make or break” a film. Well known directors can request “final cut” privileges, which allows them complete aesthetic control of the final product that is the film. Without that, producers can make editing decisions. The truest examples of Auteur theory are writers who secure the rights to direct their own work – – – – George Lucas John Patrick Shanley Andrew Niccol M. Night Shyamalan Film directors have more freedom in selection of settings and décor. It would be hard to reproduce the desert expanse that makes the C3PO shots so humorous and memorable. Directors can use special effects and miniatures to create moods and mimic realities. It is hard to imagine a theatre production that could exploit effects to this degree. The Screenplay Script – A general term for a written work detailing story, setting, and dialogue. A script may take the form of a screenplay, shooting script, lined script, continuity script, or a spec script. A script is often sold for a particular price, which is increased to a second price if the script is produced as a movie. For example, a sale may be described as "$100,000 against $250,000". In this case, the writer is paid $100,000 up front, and another $150,000 when the movie is produced. Screenplay – A script written to be produced as a movie. Shooting Script – The script from which a movie is made. Usually contains numbered scenes and technical notes. Lined Script – A copy of the shooting script which is prepared by the script supervisor during production to indicate, via notations and vertical lines drawn directly onto the script pages, exactly what coverage has been shot. Continuity Script, or Continuity Report – A detailed list of the events that occurred during the filming of a scene. Typically recorded are production and crew identification, camera settings, environmental conditions, the status of each take, and exact details of the action that occurs. By recording all possible sources of variation, the report helps cut down continuity error between shots or even during reshooting. Spec Script – A script written before any agreement has been entered into ("on spec" or speculation), in hopes of selling the script to the highest bidder once it has been completed. Treatment – An abridged script, it is longer than a synopsis. It consists of a summary of each major scene of a proposed movie and descriptions of the significant characters and may even include snippets of dialogue. While a complete script is around 100 pages, a treatment is closer to 10. Synopsis – A summary of the major plot points and characters of a script, generally in a page or two. Formatting a Screenplay Most Hollywood films are 120 minutes long; most European films are 90 minutes long. A page of screenplay—no matter if it is all dialogue, all action, or some combination of the two—equals approximately a minute of screen time. Screenplay Formula – Set-up, Exposition – Plot Point I – Confrontation – Plot Point II – Resolution pages 1-30 pages 25-27 pages 30-90 pages 85-90 pages 90-120 Formatting a Screenplay, continued Screenwriters do not, in general, have to worry about camera angles when writing. The directors will read the script or screenplay and then decide how to film it. Screenwriters need only introduce the scenes by stating whether the scene takes place inside (INT.) or outside (EXT.), where specifically it take place, and when (usually either DAY or NIGHT). These scenic cues start at the left margin. Formatting a Screenplay, continued After introducing the scene’s location, double-space and then give a description of characters or places can follow. This should not be more than a few lines long. This begins at the left margin, as well. Characters’ names are capitalized in the description as they are introduced. Once characters speak, their names, all capitalized, followed by their dialogue, is centered on the page. Formatting a Screenplay, continued Stage directions should appear in parentheses under the speaking character’s name, single-spaced. Sound effects or music effects should be capitalized within any descriptions. Common Terms Term Meaning ANGLE ON (the subject of the shot) A person, place, or thing ANGLE ON BILL leaving his apartment building FAVORING (subject of the shot) Also a person, place, or thing FAVORING BILL as he leaves his apartment ANOTHER ANGLE A variation of a SHOT ANOTHER ANGLE of Bill walking out of his apartment WIDER ANGLE NEW ANGLE POV A change of focus in a scene You go from an ANGLE ON Bill to a WIDER ANGLE which now includes Bill and his surroundings Another variation on a shot, often used to “break up the page” for a more “cinematic look” A NEW ANGLE of Bill and Jane dancing at a party A person’s POINT OF VIEW, how something looks to him/her ANGLE ON Bill, dancing with Jane, and from JANE’S POV Bill is smiling. REVERSE ANGLE A change in perspective, usually the opposite of the POV shot Bill’s POV as he looks at Jane, and a REVERSE ANGLE of Jane looking at Bill OVER THE SHOULDER SHOT Often used for POV and REVERSE ANGLE shots. We see Bill’s shoulder and head in an OVER THE SHOULDER shot of Jane Focuses on the movement of a shot A MOVING SHOT of the jeep racing across the desert. A MOVING SHOT of Bill walking toward Jane. MOVING SHOT CLOSE SHOT A close-up.Use sparingly for emphasis. A CLOSE SHOT of Bill, ecstatic, as he stares at Jane. INSERT A close shot of “something,” like a photograph, newspaper headline, or gun. INSERT of faded photograph, showing Bill and Jane’s wedding FADE IN DISSOLVE IN Ways to begin a screenplay or a scene FADE IN: ANGLE ON Bill putting on dress shoes CUT TO FADE OUT DISSOLVE TO Ways to end a screenplay or a scene CUT TO: JANE opening closet, sorting through clothing, and pulling out a flowered dress Screenplay Facts Over 15,000 screenplays are registered with the Writers Guild of America each year. About 80 to 90 feature films are made by studios and independent production companies each year. A literary agent gets a ten percent commission on anything he/she sells Prices for a screenplay vary from $400,000 to the Writers Guild minimum. – A high budget movie that costs over $1 million to make earns about $20,000 for the writer(s) – A low-budget film earns a little over $10,000 If someone options a film, they pay the writer 5-10 percent of the agreed upon price. If the option is picked up, then the writer receives the rest on the first day of shooting. More Questions for Analysis In addition to the questions provided int eh Fiction section, with drama you might ask yourself: – How do the stage/filming directions contribute to your understanding of the work? How do they go beyond what you would see if you were watching the work being performed? – How are the settings or props adding to the play or its theme? – How is the plot structured? Is it following the classical structure, or has its chronology been manipulated with flashbacks or flashforwards? Sources Field, Syd. Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting. New York: Dell Publishing, 1994. Henderson, Gloria and William Day and Sandra Waller. Literature and Ourselves. New York: HarperCollins College Publishers, 1994. Giannetti, Louis. Understanding Movies. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1999. Internet Movie Database. http:// www.imdb.com Niccol, Andrew. Gattaca. Dir. Andrew Niccol. Sony Pictures, 1994.