Running head: NEW MEDIA AND SPECIALISTS NEW

advertisement

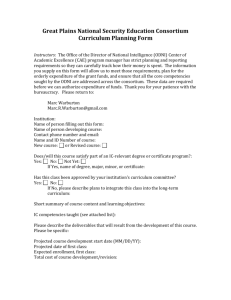

Running head: NEW MEDIA AND SPECIALISTS Are You a Specialist, or a Generalist?: The Role of the Internet in the Formation of Issue Publics 1 NEW MEDIA AND SPECIALISTS 2 Abstract The present study revisits the question as to whether U.S. citizens are information specialists or information generalists. Although the literature has presented mixed views, this study provides evidence that the changing information environment facilitates the growth of specialists. Using national survey data (n=1208) regarding the health care reform, the study found that individuals sought issue-specific knowledge driven by their perceived issue importance rather than by general education, and that this trend was conditional upon individuals’ primary source of media. Specifically, individuals who relied upon the Internet and cable TV news were capable of translating their interest in the issue into issue-specific knowledge. On the other hand, those who depended on network TV news, newspapers, and radio failed to display a high level of issue-specific knowledge, even when they perceived the issue to be important to their family. NEW MEDIA AND SPECIALISTS 3 Are You a Specialist, or a Generalist? A number of theorists have welcomed television as a “knowledge leveler” (Neuman, 1976, p. 122) that reduces the inequality in political knowledge (Eveland & Scheufele, 2000; Kwak, 1999; Prior, 2007). They suggest that incidental and habitual exposure to daily evening newscasts leads to a narrowing knowledge gap between the more and less educated citizens. More specifically, the less educated inadvertently benefit from watching television as they become generalists who are aware of a wide range of political and social issues in spite of their relatively low interest in politics. However, as the information environment changes, many have been concerned about whether new media can fully serve a function of fostering generalists (Sunstein, 2001). By virtue of decentralized media outlets and increased user controllability, individuals, especially those who are uninterested in politics, can avoid news and seek entertainment single-mindedly. Consequently, mass publics might fail to obtain the political information necessary for competent citizenship in a democratic society. Additionally, the knowledge gaps between the educated and uneducated, news junkies and entertainment fans, and the ‘‘haves’’ and ‘‘have-nots’’ widen (Bennett & Iyengar, 2008; Prior, 2007; Wei & Hindman, 2011). Despite the scholarly concerns about the decline of information generalists in the new information environment, little empirical attention has been paid to the rise of information specialists, who are knowledgeable publics within a particular domain of their interest. The changing media environment tends to cultivate information specialists by allowing them to seek information selectively and acquire domain-specific knowledge efficiently (Kim, 2009). However, one main obstacle to the research on this topic is that the concept of specialist can be fully captured only when the researcher breaks down political issues into separate issues and NEW MEDIA AND SPECIALISTS highlights each issue distinctively. 4 For example, since individuals who are specialists in a health care domain are not necessarily specialists in environmental issues, an issue-by-issue approach is necessary. Researchers need issue-oriented measures to address the issue of emerging information specialists in this changing media environment. Unfortunately, most studies on the effects of the Internet on political knowledge (Althaus & Tewsbury, 2002; Dalrymple & Scheufele, 2007; Eveland & Dunwoody, 2000) have paid little attention to systematic differences across issue domains (cf., Kim, 2009). They simply viewed citizens as an aggregated mass audience, lending little credence to the role of the new media in fostering specialists. On the other hand, the idea of issue publics provides a useful theoretical tool to address the political implications of the rise of specialists in the new media environment (Kim, 2009). The issue public hypothesis posits that citizenry consists of issue publics, or pluralistic small groups of people who are passionately concerned about certain issues (Converse, 1964). It is highly plausible that individuals who seek specialized and in-depth information through the Internet will become members of issue public on a certain issue. That is, the new media environment facilitates the formation of issue publics by producing specialists in various issue domains. The present study proceeds in two steps. The first aim of the study is to explore whether the concept of information specialist is actually useful for describing the formation of the public within a certain domain. Using a national survey about a health care reform bill in the U.S., the study examines whether knowledgeable publics in this specific domain consist of information specialists who are particularly interested in this domain, or information generalists who are generally knowledgeable about every issue, including the health care issue. I examine NEW MEDIA AND SPECIALISTS 5 each of these two competing theoretical arguments in the context of health care reform. the study investigates the role of new media in fostering specialists. Second, The study will examine whether presumably more selective media (e.g., Internet) are actually more effective in producing specialists as compared to traditional media (e.g., network television, radio, newspaper). Distribution of Public Knowledge Normative democratic theory posits that the functioning of a health democracy requires an informed citizenry whose attitudes and participation are based on a broad set of relevant and accurate information (Habermas, 1984). According to a voluminous literature on political knowledge, at least three theses have been widely accepted. First, levels of political knowledge are consequential to various democratic values, including participation, representation, and abilities to form coherent and stable attitudes (Delli Carpini & Keeter, 1996; McDevitt & Chaffee, 2000; Zaller, 1992). Second, overall levels of political knowledge in the U.S are frustratingly low (Lupia & McCubbins, 1998; Neuman 1986). Third, knowledge is unevenly distributed across the population and is associated with socioeconomic factors (Delli Carpini & Keeter 1996). However, relatively little consensus has been reached concerning the patterns of knowledge at individual levels. Who are informed citizens in each issue domain? knowledge levels fluctuating or stable across domains? Are their Reponses to these questions have varied widely but have generally stemmed from two theoretical models. The first model posits that individuals have varying interests and knowledge levels across domains and need not or cannot be experts on every issue. This model stresses the pluralism of public opinion. The next model emphasizes that public opinion is stratified. Although the average citizen may not NEW MEDIA AND SPECIALISTS 6 be knowledgeable in general, democracy functions owing to a small number of elites who are attentive, active, and are indeed well informed (Neuman, 1986). In the next few paragraphs I will examine each of these two arguments, that is, the specialist thesis and the generalist thesis. RQ1: Are people who are well-informed in a specific domain specialists or generalists? The Specialist Thesis Theoretically, the concept of issue public is a useful framework for developing hypothesis about why citizens are more likely to be specialists rather than generalists. Converse (1964) invoked issue public to provide realistic explanation of how citizens can respond to public policy in a fairly rational manner, despite their alarmingly low level of general political knowledge. For most people, once having managed their more pressing matters of family, work, and recreation, they have few resources and little energy left to study every social or political issue. Since the cost for becoming well informed is substantial, individuals are expected to focus their attention on a handful of issues at best. Thus, the theory of issue publics indicates that citizens are not generalists but specialists who are experts on a certain domain and display a high level of domain-specific knowledge (Iyengar, 1986; Kim, 2009). Two lines of empirical research have supported the view that the U.S. public is composed of specialists rather than generalists. First, a number of studies (Krosnick, 1990; Krosnick, & Telhami, 1995) reported that individuals are concerned only about a few issues and attach varying degrees of attitude importance to each issue. Krosnick (1990) found no significant correlations among various issue attitudes. For example, individuals who are information specialists in a foreign policy are not likely to be specialists in domestic social welfare issues. The findings are also consistent with evidence that citizens hold the low level of coherence across issue attitudes (Converse, 1964). NEW MEDIA AND SPECIALISTS 7 While the first line of studies examines multiple domains and their relationships, the second line of inquiries focuses on identifying informed citizens within a single domain. The latter type of inquiries attempts to investigate the specialist thesis by showing that individuals seek domain-specific information not driven by general education level but by perceived issue importance or personal self-interests (Berent & Krosnick, 1995; Kim, 2009). Numerous studies (e.g., Petty & Krosnick, 1995) have shown that people who perceive an issue as personally important tend to form a more stable attitude toward the issue and be more cognitively and behaviorally involved. One explanation is that the knowledge construct of a certain issue is more accessible when people perceive this issue to be important (Iyengar, 1990). Another explanation focuses on the selective information-seeking behaviors among specialists (Boninger, Krosnick, Berent, & Fabrigar, 1995). Specialists report a high level of domain-specific knowledge because they are committed to collect information about the issue selectively. Accordingly, Krosnick and his colleague (Krosnick, 1990; Krosnick & Telhami, 1995) argued that personal issue importance is the best proxy for identifying specialists (cf., Price et al., 2006). Since the present study does not deal with multiple domains simultaneously but focuses on the single domain of the health care reform, the study will pursue the second type of inquiry. The Generalist Thesis The generalist thesis, perhaps the most widely supported proposition for explaining the functioning of democracy, offers a rather different picture of the mass polity. This approach posits that despite the general paucity of political interest and knowledge among most American citizens, democracy functions thanks to a small number of sophisticated, educated, and attentive elites (Price & Zaller, 1993; Zaller, 1992). Although people may be more informed about one issue than the other, those who are well informed about one issue are likely to be well informed NEW MEDIA AND SPECIALISTS 8 about other issues as well (Delli Carpini & Keeter, 1996). In addition, this view indicates that education is a significant source of information for political learning. People who are more educated are presumably equipped with sophisticated cognitive ability that enables them to organize abstract ideas to understand complex political matters (Krosnick, 1990). Ample studies (Delli Carpini & Keeter, 1996; Neuman, 1986) have also provided empirical evidence supporting this view. Educated individuals are more familiar with political issues and more knowledgeable about political events (Neuman, 1986). Delli Carpini and Keeter (1996) were also skeptical about the existence of a multitude of distinct specialists. They showed that knowledge about the United Nations is a good predictor of knowledge about racial issues as well as international relations and concluded that if citizens are informed about a certain topic, they are likely to be informed about other issues as well (Delli Carpini & Keeter, 1996). On closer inspection, however, these scholars did not rule out the possibilities of the specialist thesis. After discussing the methodological difficulties of assessing the pluralistic model, Neuman (1986, p.39) remarked, “The model is not wrong, but it is incomplete.” In addition, Delli Carpini and Keeter (2002) embraced the specialist thesis more explicitly in their recent paper. While calling for more research on the effects of the Internet on the growth of information specialists, they postulated, “(the Internet) will allow citizens to focus on the specific levels of politics in substantive issues in which they are most interested” (Delli Carpini & Keeter, 2002, p. 145). Adopting this perspective, the present study hypothesizes that although both the specialist thesis and the generalist thesis are theoretically reasonable, the specialist thesis will have more explanatory power than the generalist thesis. Subsequently, the following section of the paper will provide a more detailed theoretical discussion of the effects of the new media NEW MEDIA AND SPECIALISTS 9 environment on the growth of the specialists. H1a (the generalist thesis): Individuals who are more educated are more likely to be well-informed in the issue (health care reform). H1b (the specialist thesis): Individuals who perceive the issue (health care reform) to be personally important to their family are more likely to be well-informed in the issue. H1c (the specialist thesis): Perceived issue importance will be a stronger predictor of domain-specific knowledge than education. The Role of New Media in the Growth of Specialists Traditional Media and Generalists Before hundreds of cable channels penetrated American households, most people watched television for several hours every night. They relied primarily on the evening news broadcasts by three network channels to catch up on what was happening in the world. During the heyday of network news, many Americans were exposed to the news partly because they were followed by their favorite sitcoms or because all three channels aired the news at the same time (Prior, 2007). Although some elite newspapers and magazines might provide selective, detailed, in-depth information, most citizens do not benefit from these media (Delli Carpini, 2002). For more than five decades, television has been the major source of political information. That most citizens are generalists rather than specialists relates closely with the traditional media environment described above. environment deserve particular attention here. Two characteristics of such information First, the political information supplied by traditional media outlets is sufficiently homogeneous and standardized (Neuman, 1991, Steiner, 1952). Media corporations aim to seek larger audience and maximize profits. To appeal to as NEW MEDIA AND SPECIALISTS 10 many viewers as possible, and more importantly to disturb as few as possible, the media outlets produce media content that is ideologically moderate, non-controversial, and popular (Gerbner, Gross, Morgan, & Signorielli, 1982). Accordingly, individuals’ personal tastes are ignored. Even if people have special interests in a particular domain, they might have difficulties in obtaining domain-specific information through one-way publishing or broadcasting media. Another feature of the traditional media environment is that public news exposure is non-selective or incidental (Downs, 1957). Political learning from watching television occurs unintentionally and passively (Schudson, 1998; Zukin & Snyder, 1984). Researchers suggest that incidental and habitual exposure to the evening newscasts leads to a decreased knowledge gap between more or less educated citizens (Jerit, Barabas, & Bolsen, 2006; Kwak, 1999; Neuman, 1976). This narrowing gap occurs because less educated people are accidentally or occasionally exposed to TV news programs that are easily digestible, regardless of whether or not they were particularly motivated to follow the news (Neuman, Just, & Crigler 1992). The political information reaches not only those educated and attentive but also those with low levels of political interest and knowledge, thus allowing the latter group to keep up even with their more attentive counterparts (Bennett & Iyengar, 2008). Taken together, in the traditional media environment characterized by homogenized information and non-selective exposure, the public is better described as generalists and non-generalists rather than as an assemblage of selectively informed specialists (Delli Carpini & Keeter, 2002). New Media and Specialists Contrary to traditional new media, the Internet and related media technologies allow for more diversity in media content and more selectivity in media use. First, the new media has the potential for more diversity with decreased cost and lowered space constraints. Amateurs NEW MEDIA AND SPECIALISTS 11 are capable of creating and distributing their ideas more freely, resulting in long-tail diversity (Anderson, 2006). learning. Second, the new media induce audiences’ selective exposure and selective Information is not given linearly, but is sought selectively through the technological functions, such as menu options or Google search. Here, a crucial juncture is reached where these technological affordances fit with specialists’ tendency to obtain information in only a few domains they are interested in (Kim, 2009). For example, in the traditional media environment, individuals have difficulties satisfying their personal tastes and cultivating them because the mass media usually do not provide detailed, in-depth information about specialized topics. Thus, if the mass media do not help people to specialize in a certain topic, they either give up becoming specialists or need to make additional efforts. However, since extra efforts often cost monetary resources or require human networks, those with higher socioeconomic status are more likely to be eligible for the benefits. On the other hand, in the new information environment, people can obtain domain-specific knowledge with ease and efficiency only if they have interests in a particular topic. A growing body of work lends more support to this view by highlighting differences between selective or motivated learning and incidental or passive learning. According to the cognitive psychology literature, when individuals are allowed to seek their own path of interest, their motivation to learn grows, subsequently leading to a heightened attention level (Bandura, 1982; Chaffee & Schleuder, 1986). Waal and Schoenbach (2007) found that although newspaper readership predicts higher awareness of societal issues as compared to non-readership, the relationship disappears among those who have minimal interest in the first place. finding is also reported in political contexts. A similar For example, Holbrook, Berent, Krosnick, Vissler, and Boninger (2005) found that after watching television, viewers were better able to recall the NEW MEDIA AND SPECIALISTS 12 candidates’ statements about policy issues when they had personally important attitudes towards those issues. More interestingly, they further demonstrated that attitude importance increases knowledge acquisition only when accompanied by selective exposure and selective elaboration. Furthermore, Johnson and Kaye (2000) found that those who are politically interested rely more on the Internet rather than television for news consumption. More recently, Kim (2009) showed that selectivity in the use of the web produces higher domain-specific knowledge, attitude extremity, and policy voting. Although this research sheds light on the relationship between web selectivity and domain-specific knowledge, it did not directly compare the role of different types of media in fostering specialists. Therefore, this study will further test which types of media facilitate greater growth of specialists. RQ2: Does the new media environment facilitate the growth of specialists? H2: The relationship between perceived issue importance and domain-specific knowledge (the specialist thesis) will become stronger among those who rely on new media, as compared to those who rely on traditional media. --- Figure 1 about here --Method Data come from the Kaiser Family Foundation’s health tracking survey regarding health care reform. Telephone interviews were conducted with a randomly selected national sample between April 9 and 14, 2010. Participants and Demographic Characteristics 1,208 US adults who are 18 or older participated in the survey through either landline or cell phone. Respondents contacted through a cell phone were offered $5 in exchange for their cell phone minutes spent during the interview. Subjects reported their age (M=51.5, SD=18), NEW MEDIA AND SPECIALISTS 13 sex (51.3% male), race (76.2% white), and household income (Median category=between $50,000 and $75,000). Measures Domain-specific knowledge. The study created a domain-specific knowledge index using nine dichotomous yes-no knowledge items about the health care reform bill that had been passed by Congress in March 2010. Using a split-half sample method, different sets of knowledge items were given to each half of the total sample. The domain-specific knowledge index was constructed by counting the number of items answered correctly (0=all wrong, 9=all correct, Cronbach’s α=.626, and .567 for each half1). Two split-half samples were combined for further analysis2 (M=5.8, SD=2). Main source of information. Respondents were asked what is their main source of news and information about the health reform bill (1=cable TV channels or their websites3, 2=network channels or their websites, 3=newspaper or newspaper websites, 4=other websites and blogs, 5=conversation with friends and family, 6=radio, 7=elected officials, 8=an employer, 9=community, 10=none of the above). While the majority of the respondents reported that television channels or their websites were the most important source (38.9% Cable TV channels, 16.4% network TV channels), less than 10% of respondents relied mostly on general websites and blogs (7.7%). Perceived issue importance. Respondents provided their perceptions about how much the health care reform would affect their family personally (1=nothing at all to 4=a lot). Control variables. The study includes six control variables: age, gender, income, education, party NEW MEDIA AND SPECIALISTS 14 identification, and the number of media people use. These control variables were chosen based on previous studies that examined the relationships between these control variables and either media selection or political knowledge (e.g., Shen & Eveland, 2010). Notably, the number of media people use is included in the analysis to extract the unique influence of their main media and to control the influence of other media. An index of the number of media sources used was created by counting the number of media sources respondents used to get information about the health care reform bill (M=2.7, SD=1.3). Result The study first assessed whether domain-specific knowledge is predicted by general education level or personal issue importance. predicting domain-specific knowledge. Table 1 presents OLS multiple regression models Model 1 consists of control variables including age, gender, income, party identification, and the number of media used. education with model 1. 1. Model 2 combined Model 3 incorporated personal issue importance in addition to model Finally, model 4 includes model 1 in conjunction with both education and personal issue importance. Model 1 alone explains 11 percent of the variance in domain-specific knowledge. Sex and age are not significant predictors, but individuals with higher household income (β= .115, p<.01), Democrats (β=.153, p<.01), and those using diverse media (β=.264, p<.01) are more likely to have higher scores on the health care reform bill knowledge index. To assess the generalist thesis, model 2 included the education variable in addition to model 1. The education variable did not add significant change to the variance initially explained by the model 1. R-square change = .003, F(1,930)=2.745, p-value=.098. education was also not significant (β=.06, p=.098) at the conventional level. The coefficient for Thus, the NEW MEDIA AND SPECIALISTS 15 generalist thesis (H1a) was not supported. --- Table 1 about here --In contrast, the results of model 3 suggest that perceived issue importance is a significant predictor of domain-specific knowledge. Including personal importance in the model, the R- square increased significantly (R-square change =.023, p<.01). The coefficient of the perceived issue importance variable was sizable as well (β=.16, p<.01). Finally, I included both education and perceived issue importance in the model to see if the perceived issue importance variable has explanatory power beyond the education variable. As expected, perceived issue importance remained significant (β=.16, p<.01), but education became even less meaningful in the model (β=.03, p=.246). Taken together, the data supported the specialist thesis (H1b, H1c) but not the generalist thesis (H1a). The study has shown that the specialist thesis better describes the distribution of publics in the health care reform domain. The findings indicate that well-informed citizens in the health care domain are those who think that the issue matters to them personally, not those who are more educated in general. Now, I turn to the next question by investigating the role of media environment in the growth of specialists. This cross-sectional study cannot directly compare the effects of the new media environments on issue-specific political learning with those of traditional media environment. However, the survey question asking “what is your main source of information about the health care reform bill?” allowed me to compare the characteristics of people who rely on the Internet with those who rely on television network news, cable news, newspaper, and radio. More specifically, I hypothesized that using the selective media (e.g., websites) accelerates knowledge acquisition in the domain that people think is personally important, NEW MEDIA AND SPECIALISTS 16 whereas using the non-selective media (e.g., network TV, or radio) is not so helpful for people, even in the domain that people perceive to be important. --- Figure 2 about here ----- Table 2 about here --Figure 2 and Table 2 provide support for my prediction (H2). As the specialist thesis suggests, people in general tend to have higher domain-specific knowledge when they think the domain is of great importance to them. However, this relationship disappears if people rely on network TV news, newspapers, and radio to obtain information concerning the health care reform bill. Probably, network TV news, newspapers, and radio are not so ideal for people to learn about domain-specific knowledge because this type of media usually does not provide very detailed knowledge to viewers due to the limited time and space. In contrast, the relationship between perceived issue importance and domain-specific knowledge remained significant among those who use websites and cable news channels as a main source of information. Notably, this relationship became even stronger among the website users (β=.319, p<.05). These findings suggest that website users and cable TV audiences rather than other media users (network TV, newspaper, and radio) tend to cultivate their interests more efficiently. Thus, the media that provide more specialized content are more likely to help people become specialists in the domain of their interest. Discussion Responding to recent changes in the information environment, many are concerned that these changes will make democracy more vulnerable. One such concern is that the knowledge gap between the more and less educated may expand. Since the Internet affords selective exposure, the “haves” can seek political information even more efficiently while the “have-nots” NEW MEDIA AND SPECIALISTS 17 are able to filter out political information more easily (Sunstein, 2001). that the Internet facilitates audience fragmentation. The second concern is As citizens tend to visit websites that are mostly frequented by like-minded people, they may fail to be exposed to cross-cutting views, causing their attitudes to become even more extreme (Iyengar & Hahn, 2009; Stroud, 2010). Although these views seem to be legitimate concerns, the findings of this study suggest alternative perspectives. First, concerns about the increasing knowledge gap are based on the assumption that the knowledge gap widens between the more and less educated across a wide range of issues. However, the specialist thesis, supported by the study, indicates that even though such a gap may arise, it is more likely to do so between those interested and those uninterested in a particular issue rather than between more and less educated citizens. Furthermore, given that individuals possess varying levels of interests in each issue, the knowledge gap is not uniformly processed across a wide range of issues; thus the concerns over the increasing political information inequality may not be as threatening as we think. increased specialization may not necessarily trigger audience fragmentation. Second, To the extent that the new media environment allows previously uninvolved citizens to cultivate an interest in particular domains, the new media may well function as a gateway into other adjacent domains. In addition, as people come to feel more comfortable with learning through the new media, they tend to become more politically efficacious (Delli Carpini & Keeter, 2002). Another important finding of this study is that the type of media plays a moderating role in the relationship between personal issue importance and learning. Interestingly, while patrons of network TV news, newspaper and talk radio do not reflect their knowledge in proportion to their issue importance, users of websites and cable TV news display higher level of knowledge according to their issue importance. Supporting this view, Holbrook et al., (2005) found that NEW MEDIA AND SPECIALISTS 18 the relationship personal issue importance and knowledge acquisition persists only when selective exposure and selective elaboration are allowed. If I juxtapose the present study with Holbrook et al.’s studies, the assumption is made that only two media, the Internet and cable TV, allow selective exposure while the other media do not. The findings from this study help answer some important questions about how the changing media environment shapes the formation of the mass polity while paving the way for future investigations. However, these contributions must be qualified by several limitations. First, the investigation into a single-issue domain, in this case health care reform, cannot be generalized to other domains with confidence. For instance, more polarized issues, such as welfare policy and abortion, or nationally urgent issues, such as war or natural disaster, might show entirely different pictures of the dynamics in the mass polity. Second, as the survey data are cross-sectional in nature, relationships must be qualified as correlational. Although a number of predictors, such as demographics, are clearly exogenous, the causal directions between knowledge, personal issue importance, and media use are far less clear. To make a stronger causal inference, future work is needed that involves experimental or longitudinal design. Finally, the study did not measure the degree of selectivity or content diversity directly. The study simply relied on conventional assumption that new media, such as the Internet, will provide more diverse media content and selective exposure as compared to more traditional media, such as network television and radio. This study cannot completely rule out the possibilities that other characteristics of the media facilitate the growth of specialists. One interesting question in this line of future research will be whether the Internet activity is always selective. For example, as far as the degree of selectivity is concerned, visiting the NEW MEDIA AND SPECIALISTS 19 newyorktimes.com regularly will be a different activity from typing a word in a Google search box. In addition, recent research (e.g., Lee, 2009; Waal & Schoenbach, 2007) suggests that the Internet offers various opportunities for incidental as well as selective exposure. For instance, Facebook users are incidentally exposed to provocative news articles or YouTube clips that are posted by one of their Facebook friends. Thus, it will be interesting to see whether the experience of social networking sites fosters specialists or generalists. NEW MEDIA AND SPECIALISTS 20 Reference Anderson, C. (2006). The Long Tail: Why the Future of Business Is Selling Less of More. New York, Hyperion. Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37, 122-147. Bennett, L., & Iyengar, S. (2008). A new era of minimal effects? The changing foundations of political communication. Journal of Communication, 58, 707–731 Berent, M. K., & Krosnick, J. A. (1995). The relation between political attitudes importance and knowledge structure. In M. Lodge & K.McGraw (Eds.), Political judgment: Structure and process (pp. 91-110). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Boninger, D. S., Krosnick, J. A., Berent, M. K., & Fabrigar, L. R. (1995). The causes and consequences of attitude importance. In R. E. Petty & J. A. Krosnick (Eds.), Attitude strength: Antecedents and consequences (pp. 159-190). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Chaffee, S. H., & Schleuder, J. (1986). Measurement and effects of attention to media news. Human Communication Research, 13, 76-107. Converse, P. E. (1964). The nature of belief systems in mass publics. In D. A. Apter (Ed.), Ideology and discontent (pp. 206-261). New York: Free Press. Dalrymple, K., & Scheufele, D. (2007). Finally informing the electorate? How the Internet got people thinking about presidential politics in 2004. Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics, 12,96-111. Delli Carpini, M. X., & Keeter, S. (1996). What Americans know about politics and why it matters. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Delli Carpini, M. X., & Keeter, S. (2002). The Internet and an informed citizenry. In D. Anderson, NEW MEDIA AND SPECIALISTS 21 & M. Cornfield (Eds.), In The civic web: Online politics and democratic values, (pp. 129-156). Rowman and Littlefield. Downs, A. (1957). An Economic Theory of Democracy. New York: Harper. Gerbner,G., Gross, L., Morgan, M., & Signorielli, N. (1982). Charting the mainstream: television’s contributions to political orientations. Journal of Communication, 32, 100127. Gershkoff, A.(2006). How issue interest can rescue the American public. Doctoral Dissertation. Princeton University. Habermas, J. (1984). A theory of communicative action (T. McCarthy, Trans.). Boston: Beacon. Holbrook, A., Berent, M.K., Krosnick, J.A., Vissler, P.S., & Boninger, D. (2005).Attitude importance and the accumulation of attitude-relevant knowledge in memory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 749-769. Iyengar, S. (1986). Analysis of ANES pilot study data. Paper presented at National Election Study Pilot Study Conference, Ann Arbor, MI. Iyengar, S. (1990). Shortcuts to political knowledge: The role of selective attention and accessibility. In J. A. Ferejon, & J. H. Kuklinski (Eds.), Information and democratic processes (pp. 160-185). Urbana: University of Illinois Press. Iyengar, S., & Hahn, K. S. (2009). Red media, blue media: evidence of ideological selectivy in media use. Journal of Communication, 59, 19-39. Jerit, J., Barabas, J., & Bolsen, T. (2006). Citizens, Knowledge, and the Information Environment. American Journal of Political Science, 50, 266-282. Johnson, T. J., & Kaye, B. K. (2000). Using is believing: The influence of reliance on the NEW MEDIA AND SPECIALISTS 22 credibility of political information among politically interested Internet users. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 77, 865-879. Kim, Y. M., (2009). Issue Publics in the New Information Environment : Selectivity, Domain specificity, and extremity. Communication Research, 36, 254-284. Krosnick, J. A. (1990). Government policy and citizen passion: A study of issue publics in contemporary America. Political Behavior, 12, 59-92. Krosnick, J. A., & Telhami, S. (1995). Public attitudes toward Israel: A study of the attentive and issue publics. International Studies Quarterly, 39, 535-554. Kwak, N. (1999). Revisiting the knowledge gap hypothesis. Communication Research, 26, 385-413. Lee, J. K., (2009). Incidental exposure to news: limiting fragmentation in the new media environment. Doctoral Dissertation. University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved from http://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/ Lupia, A. & McCubbins, M. (1998). The democratic dilemma: Can citiznes learn what they need to know? New York: Cambridge University Press. McDevitt, M., & Chaffee, S. (2000). Closing gaps in political communication and knowledge: Effects of a school intervention. Communication Research, 27, 259–292. Neuman, W. R. (1976). Patters of recall among news viewers. Public Opinion Quarterly, 40, 115-123. Neuman, W. R. (1986). Paradox of Mass Publics: Knowledge and opinion in the electorate. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Press. Neuman, W. R. (1991). The Future of the Mass Audience. New York: Cambridge University Press. NEW MEDIA AND SPECIALISTS 23 Neuman,W. R., Just, M.R., Crigler, A.N. (1992). Common Knowledge: News and the Construction of Political Meaning. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Petty, R. E., & Krosnick, J. A. (1995). Attitude strength: Antecedents and consequences. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Price, V., David, C., Goldthorpe, B., Roth, M. M., & Cappella, J. N. (2006). Locating the issue public: The multi-dimensional nature of engagement with health care reform. Political Behavior, 28, 33-63. Price, V., & Zaller, J. (1993). Who gets the news? Alternative measures of news reception and their implications for research. Public Opinion Quarterly, 57, 133-164. Prior, M. (2007). Postbraodcasting Democracy. Cambridge Universty Press. Schudson, M. (1998). The Good Citizen: A History of American Public Life. New York: Free Press. Shen, F., & Eveland, W. P. (2010). Testing the Intramedia Interaction Hypothesis: The Contingent Effects of News. Journal of Communication, 60, 364-387. Steiner, P. O. (1952). Program Patterns and Preferences and the Workability of Competition in Radio Broadcasting. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 66, 194-223. Stroud, N. J. (2010). Polarization and Partisan Selective Exposure. Journal of Communication, 60, 556-576. Sunstein, C. (2001). Republic.com. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Tewksbury, D., Weaver, A. J., & Maddex, B. D. (2001). Accidentally informed: Incidental news exposure on the world wide web. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 78, 533-554. Vissler,P.S., Holbrook,A., & Krosnick, J.A. (2008). Knowledge and Attitude. In W. Donsbach & NEW MEDIA AND SPECIALISTS 24 M.W. Traugott (Eds.). Sage Handbook of Public Opinion Research. 127-140. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Waal, E.de, & Schoenbach, K. (2007). How print newspapers and online news expand awareness of public affairs issues. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Communication Association, San Francisco, CA. Wei, L., & Hindman, D. B. (2011). Does the Digital Divide Matter More? Comparing the Effects of New Media and Old Media Use on the Education-Based Knowledge Gap. Mass Communication and Society, 14, 216-235. Zaller, J. R. (1992). The nature and origins of mass opinion. New York: Cambridge University Press. Zaller, J., & Feldman, S. (1992). A simple theory of the survey response: Answering questions means revealing preferences. American Journal of Political Science, 36, 579-618. Zukin, C. & Snyder, R. (1984). Passive Learning:When the Media Environment Is the Message. Public Opinion Quarterly, 48, 629–38. NEW MEDIA AND SPECIALISTS 25 Footnotes 1. Relatively low Cronbach’s α does not indicate the flaw of the knowledge index. In order to create a knowledge index that taps into multiple dimensions of knowledge (i.e., to increase validity), reliability of the measure is inevitably compromised to some extent (Delli Carpini & Keeter, 1992). 2. For simpler presentation, the domain-specific knowledge index is collapsed into low, medium, and high categories. 3. With this measure, CNN cable viewers and CNN.com users cannot be differentiated. However, this does not compromise the validity of the measure because people regularly going to CNN.com or Newyorktimes.com do not necessarily engage in selective news exposure. In fact, websites of news organizations provide visitors with a variety of opportunities for incidental exposure to a wide range of issues (Tewksbury, Weaver, and Maddex, 2001) while blogs and other specialized websites offer selective news exposure. Similarly, Waal and Schoenbach (2007) found that exposure to printed newspapers and to online newspapers did not make any difference in terms of awareness of societal and political issues. NEW MEDIA AND SPECIALISTS 26 Table 1. OLS Regressions predicting domain-specific knowledge Model 1 Model 2 (Model1+Educati on) Controls Female Age Income Model 3 (Model1+ Personal importance) Model 4 (Full Model) b ββ (S.E.) b (S.E.) β b (S.E.) β b (S.E.) β -.17 (.13) -.00 (.00) .10** (.03) -.17 (.13) -.00 (.00) .07** (.03) -.04 -.14 (.13) -.01 (.00) .08** (.03) -.03 -.14 (.13) -.01 (.00) .06* (.03) -.03 .08# (.05) .06 .05 (.05) .37** (.080 .04 -.04 -.03 .12 Education Perceived importance R-square R-square change from model1 Note: # p<.1. * p<.05. -.03 .09 .38** (.08) .117** .11** .12** .00# ** p<.01. n.s. = non-significant -.05 .09 .16 .13** .02** -.05 .07 .16 .14** .03** NEW MEDIA AND SPECIALISTS 27 Table 2. OLS Regression predicting domain-specific knowledge X main source of information Main source Perceived RN of importance square information b (S.E.) Standardized β Cable TV .090* .109 .142 416 (.044) Network TV .096 n.s. .131 .088 176 (.066) Newspaper .062 n.s. .073 .123 150 (.085) Website .229* .319 .282 82 (.097) Radio .105 n.s. .158 .056 106 (.075) The regression model includes control variables (sex, age, income, education, party identification, and the number of media sources used). NEW MEDIA AND SPECIALISTS 28 Type of Media H2 Perceived Importance H1b, H1c Domain-Specific Knowledge Education H1a Figure 1. Hypotheses NEW MEDIA AND SPECIALISTS 29 6.8 .319* 6.6 6.4 DomainSpecific Knowledge (DV) n.s. n.s. 6.2 n.s. .109* 6 5.8 5.6 5.4 Cable (n=416) Network (n=176) Webiste (n=82) Newspaper (n=150) Radio (n=106) 5.2 Low High Perceived Issue Importance (IV) Figure 2. Predicting domain-specific knowledge with perceived issue importance X main source of information (media type). Note: This regression model includes control variables: sex, age, education, income, party identification, and the number of media sources used. The values on the graph represent standardized coefficients (β) of perceived issue importance in the regression model.