Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale-Revised CAMS-R

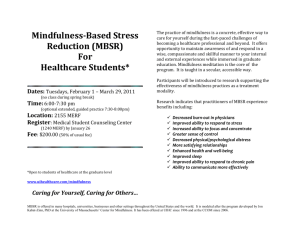

advertisement